Renters are making up an increasing chunk of the population of marginal electorates across Australia, signalling their growing political power.

Since 2001, the share of Australian homes that are rented, rather than owned, by their occupants has risen from 26.3% to 30.9%.

But those nationwide figures don’t tell the whole story. Where those renters live matters. Because marginal electorates are likely to decide who forms government at the next election, the population of renters in those seats is a particularly useful indication of how much political influence they could have.

The more renters in these tight-race seats, the likelier it is that political parties will woo them with policies designed to make renting easier or more affordable.

BuzzFeed News crunched the numbers at both the federal and state/territory levels, looking at data from the last three censuses, to find out how much political power renters could wield.

In most (36 out of 52) marginal federal seats, the proportion of renters grew between the 2011 and 2016 censuses. In all but three of those 52 seats, the proportion of rented properties increased between 2006 and 2016.

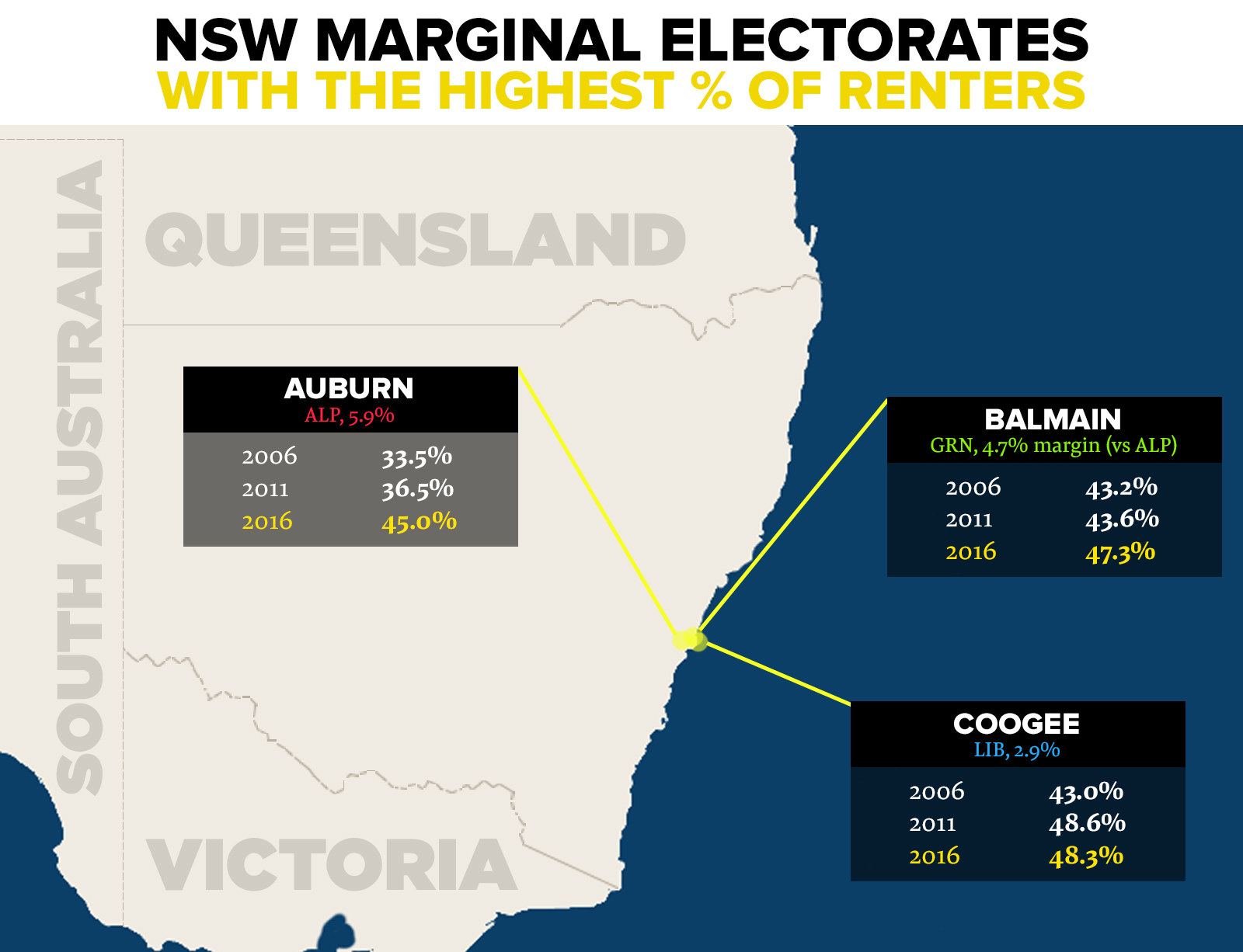

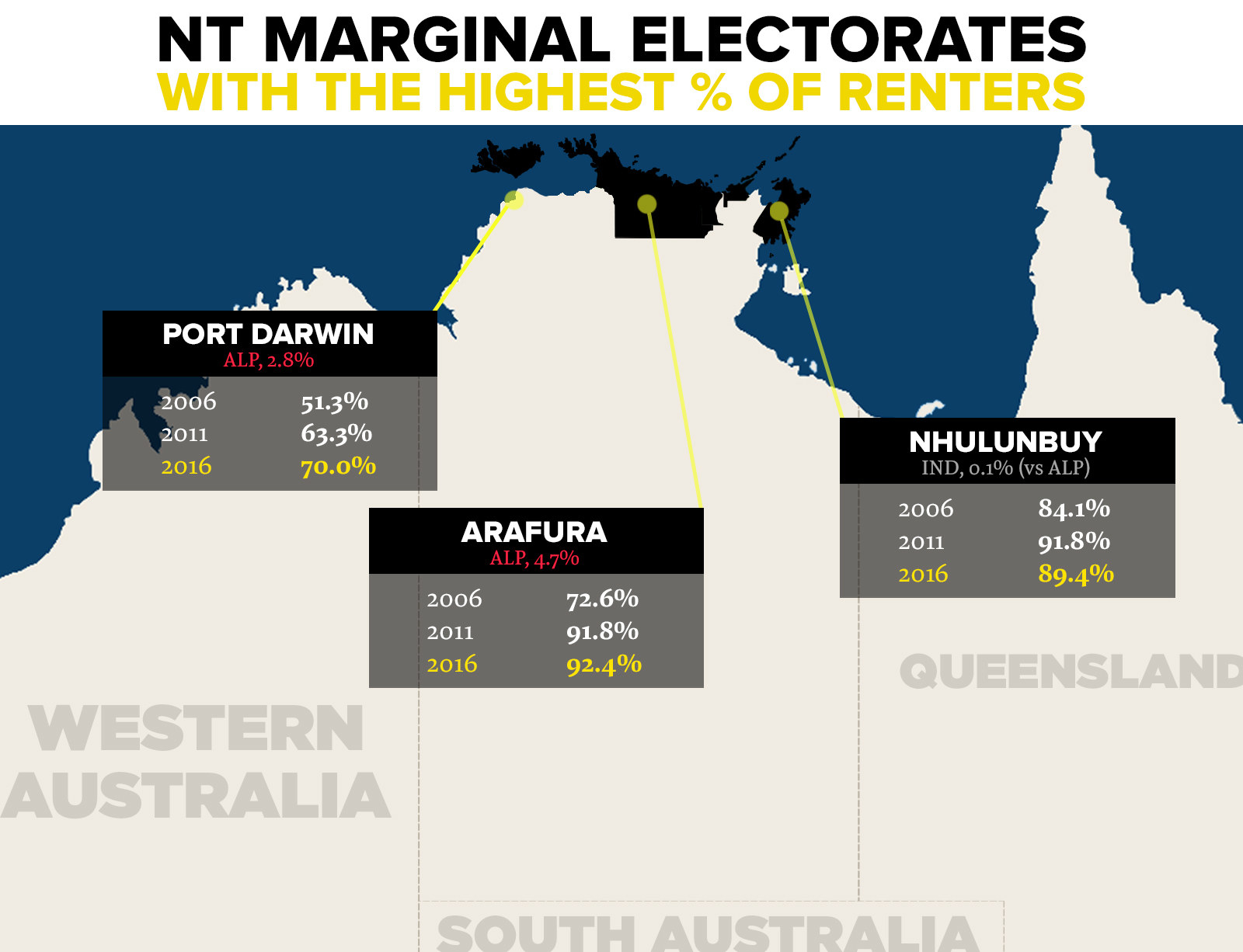

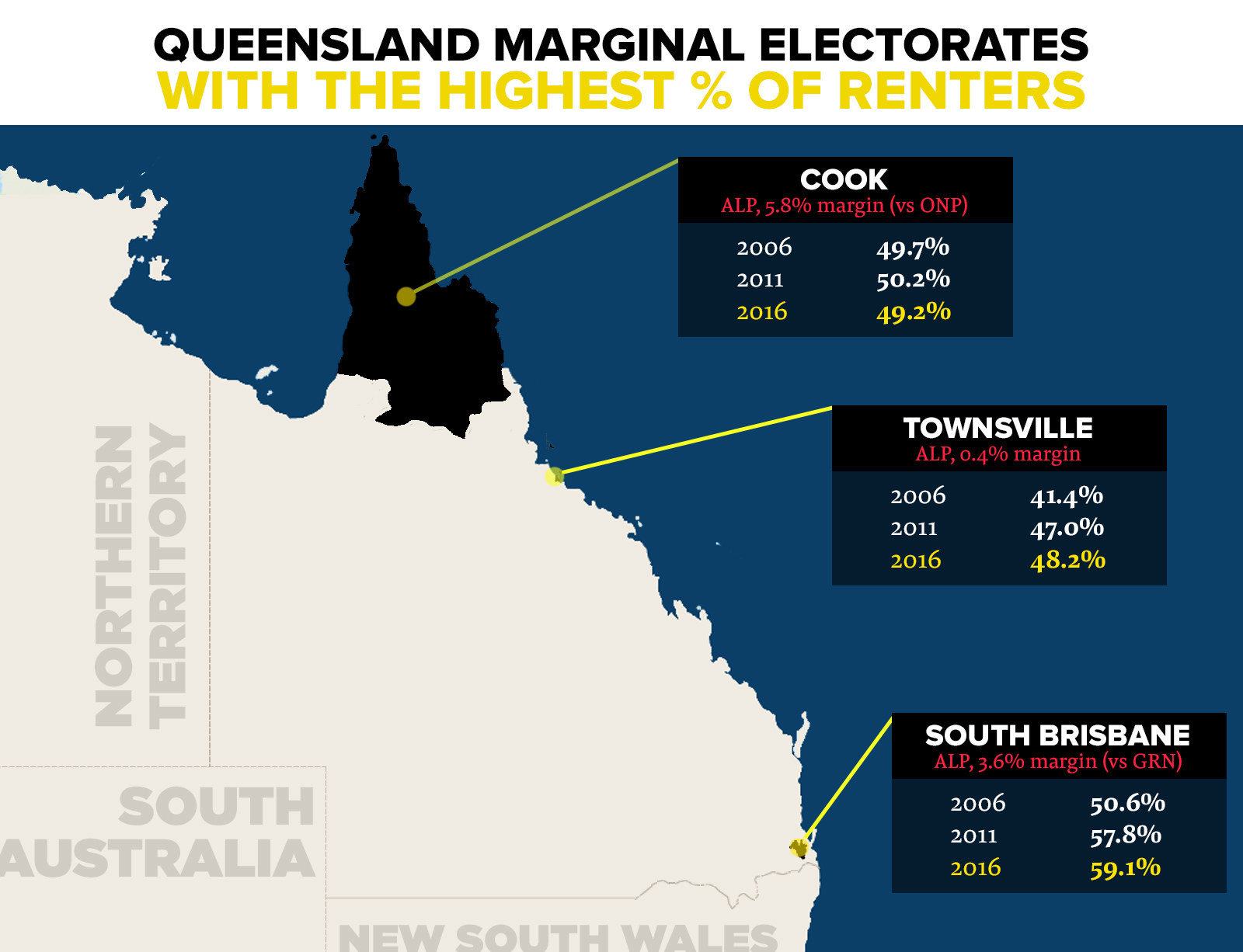

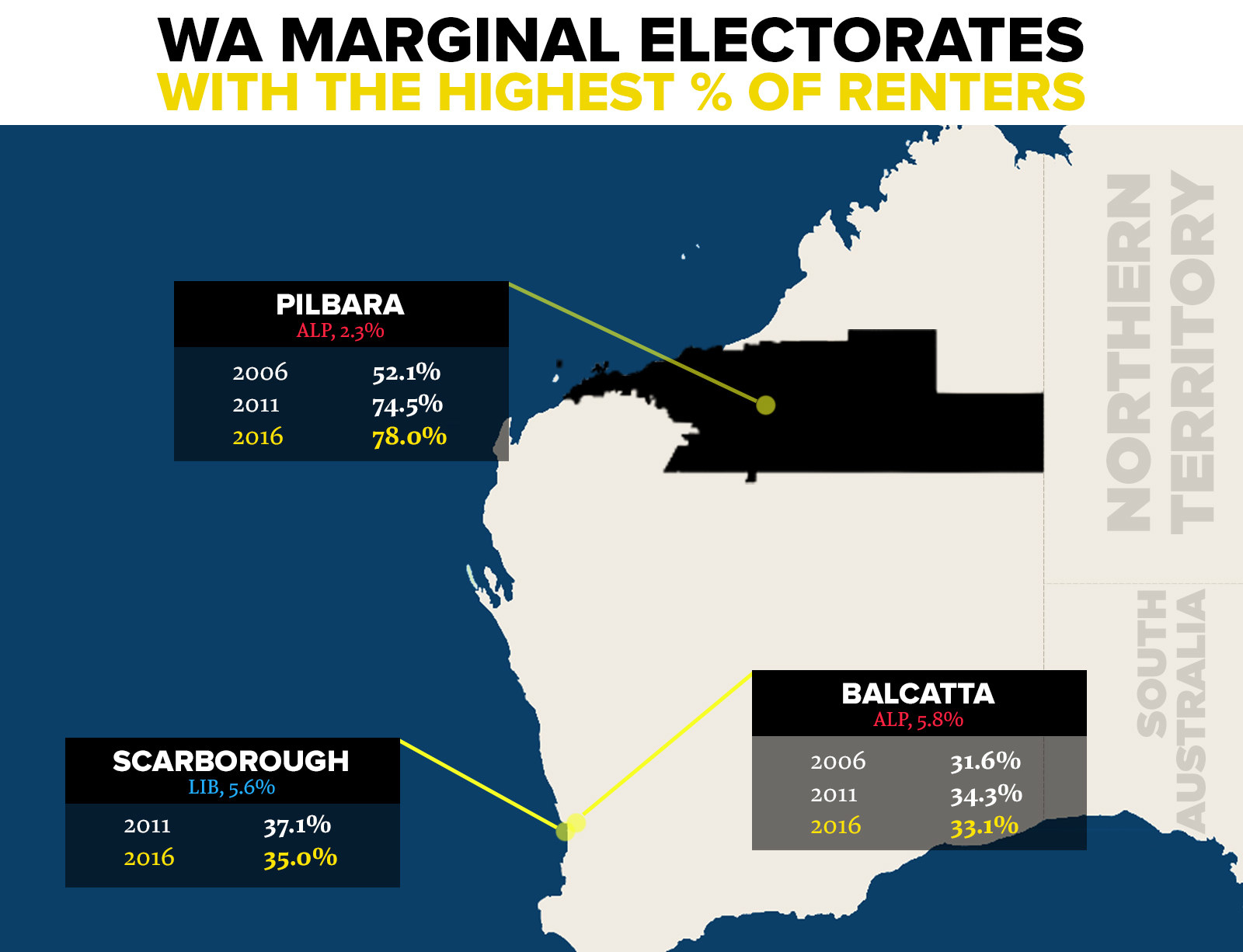

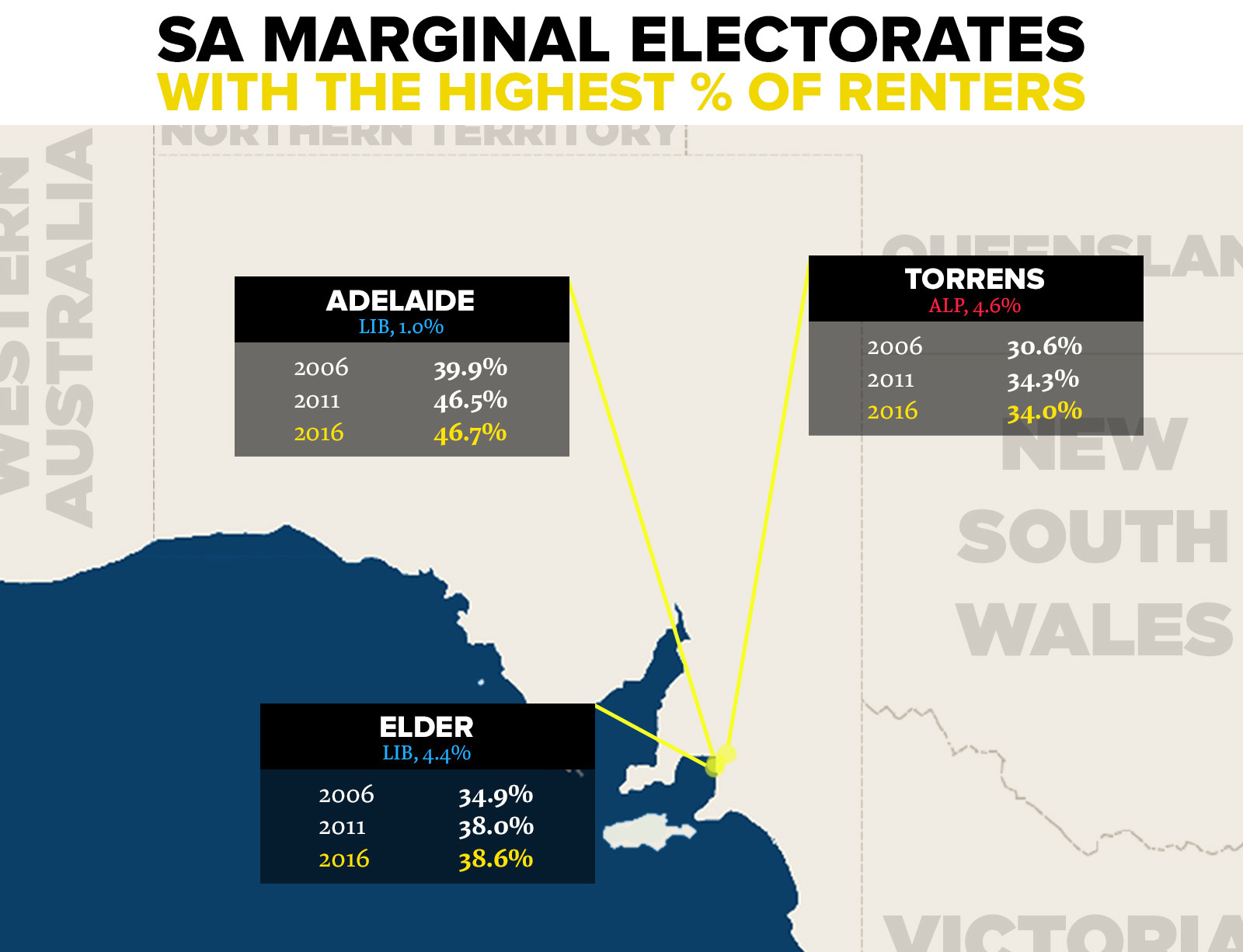

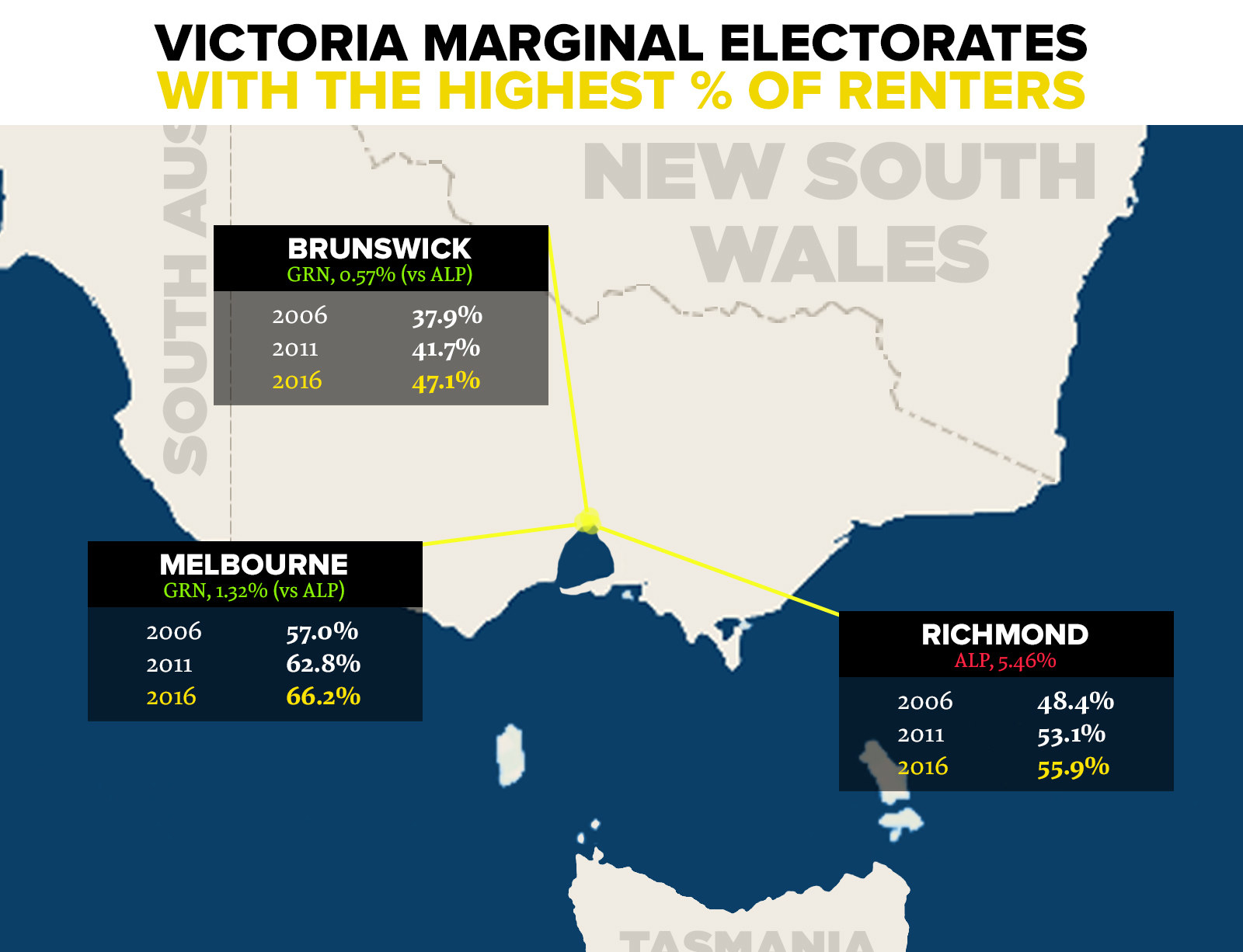

Electorates at the state and territory level are also important to consider, because it’s at that level that the basic rules that govern renting are legislated. The numbers of renters in those marginal electorates are also growing, with some sailing past the 50% mark, and particularly strong numbers in inner-city electorates. In Queensland, NSW, Victoria, South Australia, and the Northern Territory, a majority of marginal electorates saw renting numbers increase between the last two censuses.

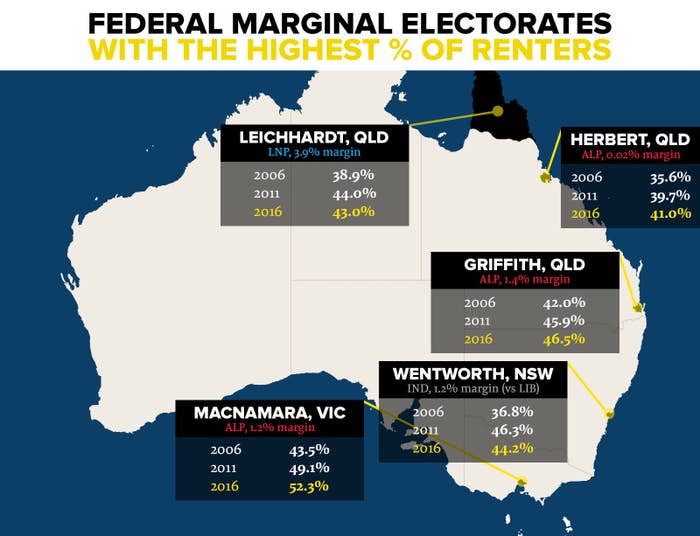

Here’s a closer look at the numbers in marginal electorates.

Note that the numbers are approximate in some cases because electoral boundaries have changed since the censuses were taken. As well, the census doesn’t measure the exact number of renters, but the number of dwellings that are rental properties. The census also does not count the number of investors/landlords – the most likely cohort to be opposed to renter-friendly policies – so it is not possible to compare the numbers.

Australia

On the national level, conversations about housing have tended to focus on investors and home ownership. But with a federal election looming, the major parties are busy trying to win every vote. Labor has courted renters by promising to spend $6.6 billion over a decade to subsidise new homes to be built and offered at below-market rent – a plan they’ve argued could mean a family paying the national average weekly rent of $462 could save $92 a week.

Meanwhile, the Coalition is arguing strongly that Labor’s plan to wind back negative gearing will raise rents. But that policy, designed to make it easier for first home buyers to enter the market, is likely to appeal to those renters who aspire to home ownership.

Of the 52 marginal seats that will be fought over in the coming months, the proportion of rental dwellings increased in 36 of them between the 2011 and 2016 censuses, and in all but three of them between the 2006 and 2016 censuses.

In a number of ultra-marginal seats – held by a margin of 1% or less – renters make up a bloc worth reckoning with. The most marginal seat of the country, Queensland’s Herbert, is held by Labor’s Cathy O’Toole by just 0.02%. There, renters make up 41% of households – far above the national average. And in Queensland’s Capricornia, Forde, and Flynn, over one-third of dwellings are rentals (33.4%, 34.5%, and 33.8%, respectively). In those seats, Labor only needs a small swing to take them off their Liberal National members, Michelle Landry, Bert van Manen, and Ken O’Dowd.

Renters are particularly powerful in the seats of Macnamara (formerly Melbourne Ports, in Melbourne’s inner city), in which 52.3% of households are rentals, Griffith in inner-city Brisbane (46.5%), and Sydney’s Wentworth (44.2%).

New South Wales

Northern Territory

Queensland

Western Australia

South Australia

Victoria

Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory

Tasmania and the ACT don’t have marginal seats in the same ways as the other jurisdictions. The ACT parliament only has one house, which uses a proportional representation voting system where multiple candidates are elected from five electorates. Tasmania uses that system in its lower house; while its upper house has single-member electorates, they don’t determine who forms government. That means we haven’t included Tasmania and the ACT here.