An official Australian government policy states that requests by doctors for sick refugees to be sent to Australia for medical care from Nauru and Manus Island will not be considered unless the person is facing a "life-threatening medical emergency that would otherwise result in their death or permanent, significant disability".

Marked "PROTECTED: Sensitive", the Department of Home Affairs document from June 2018 covers health care in "regional processing countries" — Nauru and Papua New Guinea. BuzzFeed News obtained the document through freedom of information processes.

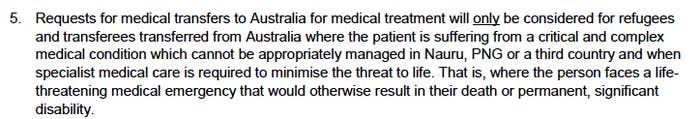

The policy states that requests for medical transfers to Australia will only be considered if the person requires specialist medical care to "minimise the threat to life" from a "critical and complex medical condition".

"That is, where the person faces a life-threatening medical emergency that would otherwise result in their death or permanent, significant disability," it reads.

Dr Barri Phatarfod, a Sydney GP and president of Doctors 4 Refugees, described the policy as “dangerous”, arguing that the threshold for transfer needed to be lower.

"If you’re only looking at people who have a life-threatening condition, it invariably means that some people will not survive," she told BuzzFeed News.

In Australia "the benchmark for transferring someone to hospital for appendicitis is not if you’re convinced they have appendicitis, but if there’s a possibility they have appendicitis," said Dr Phatarfod.

"Many of the cases that go to hospital don’t have it, but it’s better than them rupturing an appendix at home or in a shopping centre where you could have a potentially fatal outcome," she explained.

In 2014 24-year-old Hamid Khazaei died after contracting an infection in his leg on Manus Island. He presented with flu-like symptoms and was transferred to a Port Moresby hospital three days later, where he had a series of cardiac arrests. The next day he was transferred to Brisbane, but died a week later.

A coroner later found that if he had access to Australian-level health care Khazaei would not have died.

Khazaei's condition "deteriorated very rapidly", said Dr Phatarfod, and the evacuation came too late. "You can’t have somebody who needs to be in a critical state [before being transferred]. That needs to be revised."

Dr Phatarfod pointed to the difficulty in arranging a medical evacuation for a critically ill patient. She said even in a best case scenario, where a medivac plane is ready and a pilot is available, it would be a 12-hour trip to get the plane from Australia to Nauru and back again. "A lot can happen in 12 hours," she said.

Dr Phatarfod told of a woman who was raped on Nauru and has experienced vaginal bleeding for the past two years.

"Is she going to die tomorrow morning? Maybe not. But that absolutely needs to be investigated," she said.

Dr Paul J. Stevenson OAM is a consultant psychologist and traumatologist who has spent time on both Manus Island and Nauru. He described the health care available on both islands as "third-world" and "under-facilitated".

He said that in his experience, even when patients were critical, transfers were delayed or refused. However, he said, "it was relatively easy to send home sick security guards and Australians" on commercial flights.

The policy document outlines five "health service delivery principles", which prioritise providing health care on the islands.

If treatment is not available on Nauru or in PNG the contractor can arrange for a specialist to visit the island.

Dr Phatarfod said that it was often difficult to get a specialist to go to Nauru or Manus, pointing to the time a medical contractor resorted to using LinkedIn to try to recruit neonatologists to go to Nauru at short notice to assist a 40-week pregnant woman expecting a complex birth.

If it is not possible to fly in a specialist, the health service provider (HSP), such as the International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) can recommend the transfer of a person to a third-party country like Taiwan.

The Department of Home Affairs body charged with deciding whether people can be transferred to Australia has grappled with this strict policy.

Minutes of the meetings of the Transitory Persons Committee, a group of public servants that considers requests for transfers, show the group has struggled to interpret the document.

At a meeting in June 2018, the minutes say members "discussed the level of compassion to be shown and if there is any compassion in the policy". They do not state what the group concluded.

A particular point of contention is what happens when patients are offered transfers to third countries but refuse.

The first principle in the policy is that patients have "self-determination" in declining treatment.

The issue arose at two meetings of the Transitory Persons Committee in June 2018, where patients had declined transfers to Taiwan. At the second meeting, the acting chief medical officer Elizabeth Hampton argued that because Taiwan was willing to accept the patient, bringing them to Australia "goes against the policy".

Another member questioned that interpretation, suggesting that the patient's refusal could mean Australia was an option. A third member, first assistant secretary of property and major contracts David Nockels, supported Hampton's interpretation.

"Nockels raised concerns with dealing with a person holistically as that may open the door for all cases to transfer to Australia," the minutes record. "Nockels noted that if we do allow [the patient] to transfer to Australia it will null and void Taiwan and any other third country option and undermine the policy."

Medical transfers are currently the subject of fierce political debate, with a bill due to be voted on this week that would give doctors greater control over the process and override the home affairs policy. The bill would allow two treating doctors to recommend a patient be transferred if they require medical treatment, with no requirement that the person be facing death or permanent disability. The immigration minister could veto the transfer on grounds of national security or medical necessity, with an independent medical panel given oversight over decisions on the latter ground.

BuzzFeed News has approached the Department of Home Affairs for comment.

The full policy document is available here.