“Male or female?” the stranger asked me.

I was 21, standing in a brightly lit 7-11. All I wanted to do was buy my siblings Slurpees.

I was so surprised by the casual way this person had decided to interrogate my gender that I accidentally blurted out, “Male!” and then, realizing my mistake, “No, no — I mean female!” My face burned as I carried the ice-cold drinks to the counter.

The stranger grinned at me, as if we were sharing something intimate. “Duuuude,” he said, putting on his Ray-Bans, “You said male first.”

I got back into my car in silence. My sister repeatedly asked me what was wrong. So I told her, adding a laugh to assure her that I was okay. But seconds later, as I reversed out of the parking lot, I crashed into the passenger side door of a crème-colored sedan. Everyone involved in the accident was unhurt, but both cars became crumpled metal at the point of impact.

For over a decade, I’ve had experiences likes these: public instances where I have been mistaken for a man. And while each incident hasn’t resulted in a car crash (my car insurance rates are doing fine), I’m always left disoriented, wondering which fragment of my identity was responsible for the misdirected sir, the muffled joke. On some days, I decide it’s the automatic way most people associate tallness with maleness. Other times, I wonder whether it’s my deep voice, an androgynous outfit, or a short haircut that provoked the reaction.

But I’ve also been well aware that my race and gender play a huge part in these misconceptions. I have lived long enough in the world to notice that black women are rarely allowed full access to their femininity.

It was no accident that a random white dude in a 7-11 thought it was perfectly okay to ask me if I was a woman.

Sojourner Truth might have never actually asked the famous question attributed to her. A former slave, she is best known for her fiery speech at an Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in 1851. According to a transcription of the speech by women’s rights activist Frances Dana Gage, published in the New York Independent in 1863, Truth repeatedly asks rhetorically: Ain’t I a Woman? But there’s also a different existing transcription of the speech written by Truth’s friend and reporter Marius Robinson, in which Truth never asks the question at all. While many historians think this other version is more likely to be accurate, it is less widely known. The Ain’t I a Woman? iteration, instead, is what many students will read if they take a Black Feminist Thought 101 elective.

Assumptions that black women are nonfeminine have been firmly embedded throughout US history. “If black women in America are stereotyped as unshakable, our research shows that there is another closely linked myth that persists: that Black women are less feminine than other women and, in fact, even emasculating,” write journalist Charisee Jones and academic Kumea Shorter-Gooden in Shifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in America. “The myth sprang to life in the characters of Mammy and Sapphire, then evolved into the archetype of the coarse, sassy Black girl, a ubiquitous image in popular culture … such images take an immeasurable toll on the psyche of Black women, who in their desire to be seen as ladylike, to challenge the notion that they are less feminine, may affect a way of talking or behaving that does not reflect who they are.”

Black women are constantly perceived as having attributes often assigned to masculinity; we are read as “strong,” “indestructible,” “invulnerable to pain.” A 2014 OkCupid study of the dating habits of its users revealed that 82% of nonblack men had a bias against black women. Serena Williams has been likened to a man, alongside her older sister Venus; her impressive, beautiful body scrutinized for most of her career. Leslie Jones was subjected to outrageous racist and sexist trolling before the Ghostbusters movie premiere. A West Virginia official considers it perfectly fine to call Michelle Obama an “ape in heels.” A 5-foot-3-inch black woman scares a tall white man so much he shoots her in the face.

My existence in my tall, dark-skinned black woman body means that I’ve constantly had to confront gendered assumptions assigned to black women en masse, and to face the ways I’ve internalized many of these painful ideas. While today I can say that I inhabit my femininity in a way that’s significantly less dependent on external validation, the path to this inner conviction was far from simple. I spent too much of my time grappling with the question Ain’t I a Woman? — not because I was unsure, but because the world so often seemed to be.

I’ll never forget the first time I was misgendered. I was at the New Mexico State Fair as a recruit-in-training at a private military college in Roswell, New Mexico. It was our first “liberty” — for a full day, all cadets could be off campus grounds. Even though we were still required to wear our uniforms, it was going to be a fun day.

I spent too much of my time grappling with the question Ain’t I a Woman? — not because I was unsure, but because the world so often seemed to be.

I was hanging out with my pretty friend Lauren, who’s light skinned and short, and about half of the men’s basketball team were tailing us, all eager to get her number. We made our way to the Test Your Strength game, and the guys hung back, flirting with my friend as I walked ahead.

“Step right up, my good sir!” the game attendant bellowed at me in what can only be described as a circus voice.

I was mortified, and hoped that the guys did not hear, but the light cackling behind me dashed those hopes. The attendant, flustered, offered up five hundred apologies and a free swing with the hammer. I hit the large black button half-heartedly, and even though I get nowhere near “Mega Strength,” the attendant awarded me first prize — a four-foot stuffed Clifford dog.

“It’s the uniform,” he said, as I walked away, the red dog slung underneath my arm.

Maybe this time I was misgendered because of my boxy, straight-cut Army uniform. But, even before that experience, I have always felt like my femininity was never assumed.

If all girls were supposed targets for the evils of the world, then why was I never assumed to need the same kind of post–school dance chaperoning as my white friends in junior high? Why was I instructed to “toughen up” and affixed with the label of “strong” before I even entered grade school? As a kid, I just didn’t get it. Not completely, anyway.

Women don’t have to be dark-skinned Amazonians like myself to be forced to endure gender policing. In Hunger, Roxane Gay’s latest memoir, the author details the numerous times strangers failed to see her as a woman solely due to her weight. And it is butch-presenting women or trans women of color who will be most subjected to violence and even death because of their assumed gender.

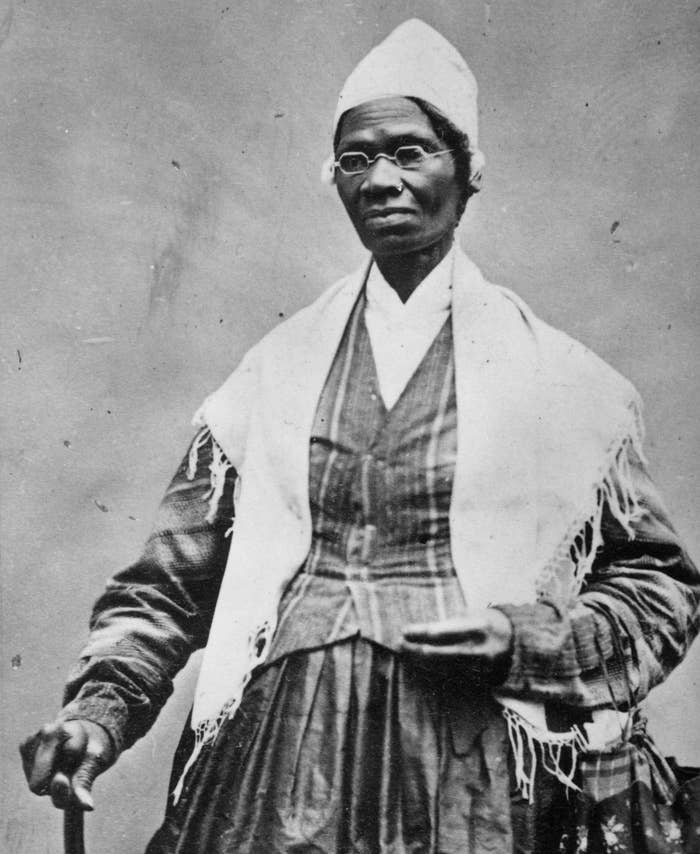

Having one’s femininity questioned and then disregarded is an experience Sojourner Truth knew all too well. According to Princeton historian Nell Irvin Painter, author of Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol, Sojourner nee Isabella was born in the late 1790s in upstate New York to James and Elizabeth Baumfree, who were slaves under Johannes Hardenbergh. Her life was never far from the blatant cruelties of American slavery: constant sexual abuse, poor living conditions, abrupt and devastating familial separation. Isabella gained her freedom in 1826 and renamed herself Sojourner Truth in 1843.

“We think of Truth as a natural, uncomplicated presence in our national life. Rather than a person in history, she works as a symbol. To appreciate the meaning of the symbol — Strong Black Woman — we need know almost nothing of the person,” writes Painter. “As an abolitionist and a feminist, she put her body and mind to a unique task, that of physically representing women who had been enslaved. At a time when most Americans thought of slaves as male and women as white, Truth embodied a fact that still bears repeating: Among the black are women; among the women, there are blacks.”

"At a time when most Americans thought of slaves as male and women as white, Truth embodied a fact that still bears repeating: Among the black are women; among the women, there are blacks.”

Most writings during Truth’s time are breathless in their physical descriptions of her. To Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she was the “Libyan Sibyl,” a reference to a North African prophetess painted on the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo. In her preface to the Ain’t I a Woman speech, Frances Dana Gage wrote that Truth was a “weird, wonderful creature” with “an almost Amazon form, which stood nearly six feet high, head erect, and eyes piercing the upper air like one in a dream.” Gage’s description also has Truth baring her arm up to her shoulder to the audience. This is the image of Truth most American children will witness during their abbreviated Black History Month lessons, a tall, dark-skinned black woman showing off her muscles like a Venice Beach weightlifter, her body a testament to the way she subverts traditional notions of femininity.

When I played college basketball, there was always a chance that at an away game, a loud-mouthed frat boy might ask the referee if I was really female, audibly hypothesizing whether I was taking steroids. I knew such remarks were trash talking at their most base, and often pretended not to hear them, but the truth was something more complicated. I was hurt, but I was also confused: I played alongside white women just as tall and strong as I was. Why weren’t these bros directing their femininity policing and insults toward them? What was it about my body that attracted such scorn and doubt?

“Society remains uneasy with female strength of any stripe and still prefers and champions delicate damsels — an outdated sentiment that limits all women,” black feminist writer Tamara Winfrey-Harris writes in The Sisters Are Alright: Changing the Broken Narrative of Black Women in America. “But because the damsel’s face is still viewed as unequivocally white and female, it is a particular problem for black women. As long as vulnerability and softness are the basis for acceptable femininity (and acceptable femininity is a requirement for a woman’s life to have value), women who are perpetually framed because of their race as supernaturally indestructible will not be viewed with regard.”

Even with boundary-pushing artists like Grace Jones — utterly flamboyant in her gender-bending outfit choices — to look up to, I have still been anxious about walking the tightrope of femininity. When I was younger, I wanted a Nia Long pixie cut but was nervous about the possible increase of sirs. I was nervous about being seen in my basketball warm-ups for too long. Shit, for a while, I was even embarrassed about the fact that my initials are HE. I wish I wasn’t so uneasy about my gender presentation back then — in addition to being a source of significant anxiety, there were a lot of thrift store tuxedos I missed out on.

I’m supposed to go to frustrating lengths to “prove” I’m feminine and offset my blackness (keep my hair long, my voice soft, my clothes appropriately girly), while women who are white or lighter in appearance are given more latitude for experimentation. Diane Keaton and Cara Delevinge “play” with tomboy styles. When a white movie star cuts her hair to pixie length or shorter, she’s gamine or elegant. To be sure, black women can and do don these sort of androgynous looks and hairstyles, but they are often read differently on our bodies: Elegant transforms into militant, boyish into manly.

Blackness, especially when attached to a black woman’s body, is overwhelmingly gendered masculine. “When antebellum middle-class white women were ‘angels of the house’— beautiful, pious, chaste, and delicate — black women were thought to be the beasts in the fields, who did not need their bodies, sensibilities, and virtue protected. While the 19th-century slavery-based American economy depended on this distinction, the bestial view remained long after black bondage passed away,” writes Winfrey-Harris. The tenets of white femininity fail to stand on their own unless we are constantly reminded of their shadow: the strong, masculine black woman.

Gage’s strident, rabble-rousing account of Truth’s Ain’t I a Woman speech is very different than the retelling from Robinson, who wrote about the same speech in 1851, only weeks after the convention took place.

Serving as secretary of the convention, Robinson writes that Truth asked permission to speak — very unlike the aggressive takeover that Gage portrayed. The real Sojourner Truth “took pride in speaking correct English and objected to accounts of her speeches in heavy southern dialect,” Painter writes. In fact, Truth’s first language, under the Hardenbergh family, was Dutch, and she most likely would not have learned English until she was sold to the English-speaking Neely family at 9 years of age.

The tenets of white femininity fail to stand on their own unless we are constantly reminded of their shadow: the strong, masculine black woman.

The most most notable absence in Robinson’s account of Truth’s speech is the “Ain’t I a Woman?” refrain. Painter notes that, while Robinson may have missed the question once, it is highly unlikely he missed it four times (the number of times it is repeated in the Gage version): “Gage’s rendition of Truth far exceeds in drama Marius Robinson’s straightforward report from 1851. Through framing and elaboration, she turns Truth’s comments into a spectacular performance four times longer than his.” Gage wanted to write something dramatic — she didn’t necessarily want to report the truth.

It was not Truth who needed to ask the mainly white audience whether she was considered a woman — it was Gage. Writing in competition with Harriet Beecher Stowe and to further her own cause as an advocate of women’s rights, she boldly created the caricature of the Sojourner Truth we most know today. Unable to attach a concept of strength to the white women she was primarily fighting for, Gage relied heavily on Truth’s “strong” black body to do the work of convincing her readers that women were not so delicate that they could not entertain the rights and privileges of men. She needed the symbol of Sojourner Truth to win this battle; an honest account that took Truth’s complicated humanity into account would just not do.

Once I almost got into a fight with a guy on the Lower East Side after he called me a man. It was 2014, seven years after the 7-11 incident. A new friend and I were leaving a burlesque show in the city on a sticky summer evening. A man started to follow us, yelling about his sexual prowess to my friend, who blatantly ignored him. I was sure he’d become bored, but one block turned into three, so I finally turned around to face him.

“Look, man, she doesn’t want to talk to you,” I said.

He rested his eyes on me. “What are you, some fucking man?” he spat out.

“Sure, I’m a fucking man,” I said.

And then I slapped him across the face.

I hadn’t been in a fight since the fifth grade, and here I was, coolly slapping a stranger in the middle of New York City.

For the next couple of minutes, me and Lower East Side Guy argued. He was embarrassed and wanted to fight. My friend weakly tried to pull me away. Eventually, we all walked off, but for the rest of the night I kept thinking about the man’s question and my own response. I wondered why I had so readily taken on the identity the man thrust upon me, why I had let him anger me so much that I physically acted out. The night could have ended so much worse than it did. There was no way I could no longer pretend that these altercations did not affect me.

The next day, I worked my volunteer shift at a self-defense nonprofit fundraiser. Coincidentally, this year it was a punch-a-thon held at Prospect Park, and a large circle of people, mainly women, were punching to counts of ten. I punched the air in front of me and thought about the night before. Twice in seven years, I had verbally identified myself as a man. One time was a blurry mistake, but this latest was because I knew the man could not seem to see me as anything else. How long would I erase my femininity just because the world asked me to?

Sojourner Truth didn’t have a say in the way her black femininity was coded in America. She has largely become a one-dimensional symbol in our public imagination, asking that one question we all know so well every February. We reprint a white woman’s words next to her portraits on T-shirts and tote bags. Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, and Kerry Washington have all read versions of the Gage speech, and bell hooks’ landmark text on intersectional feminism carries Ain’t I a Woman? as the opening title. We diminish the fact that this illiterate former slave lectured throughout the United States in a time when even white women encountered significant obstacles to public speaking. Many don’t know that Truth was the first black woman to win a court case against a white man (when her son was sold illegally across state lines) in 1828. Instead, we’d much rather just keep asking the same damn question.

How long would I erase my femininity just because the world asked me to?

Painter has consistently found that, despite her substantial study and biography of Truth, most people, including the Princeton students she teaches, prefer the Sojourner Truth that Frances Dana Gage created. Though Painter has researched the many ways in which Gage’s account doesn’t line up — the time lapsed between the event and the report, the inaccurate dialect, the obvious agenda Gage had for her women’s rights work — not many people doubt Gage’s version. Most are satisfied to believe in the Truth that remains towering, masculinized, unchanging.

Of course, piecing together historical facts from a bygone era will always be difficult. The Narrative of Sojourner Truth offers some glimpses of the complexity of this magnificent woman, but since this book was not actually written by Truth (she dictated her story to Olive Gilbert), we still do not know what was omitted, what was colored in and sensationalized for white audiences.

Unlike Truth, I live in a world where I can fashion my own story — even as the outside world interjects. And through a mix of feminist self-inquiry and a heavy dose of burlesque classes, I have done just that. As a black woman, the world will scarcely recognize my complexity, but I am no longer waiting for them. After almost a decade of worrying and deconstructing the racist storylines of those around me about my femininity, I’ve set off to reclaim what was always mine to begin with. No questions asked. ●

CORRECTION

Marius Robinson wrote the different version of Sojourner Truth's speech. A previous version of this story misstated his name.