“Let’s talk taboos!” the emcee said, and the women did.

Dozens of Muslim women at an empowerment conference heard lectures on sexual pleasure, HIV, and hymens, eyebrow-raising topics for the most conservative members of Dar al-Hijrah Islamic Center, the Virginia mosque that organized the event. Some in the audience blushed; others cheered.

The girl-power exuberance faded, however, when it came time for the most delicate issue of the day: female genital mutilation, or FGM, an ancient ritual the United Nations defines as the partial or total removal of external female genitalia for nonmedical reasons. For many who undergo it, the cutting leaves traumatic memories and can cause lifelong health complications.

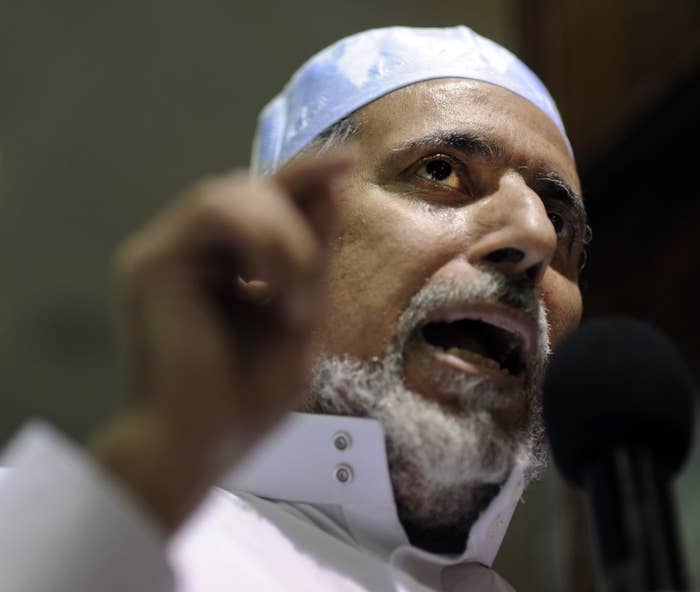

Given all the taboos involved, FGM isn’t an issue most US Muslim communities address unless they’re forced to. That was the case with Dar al-Hijrah last spring when the imam, Shaker Elsayed, offered religious justification for the “circumcision” of women and girls. In countries that have banned the practice, he warned during a lecture, “hypersexuality takes over the entire society and a woman is not satisfied with one person or two or three.”

His words turned Dar al-Hijrah into a battleground for a new movement — led by Muslim women, some of them self-described “survivors” of the practice — to break US Muslims’ silence on FGM. That fight is complicated by the politics of the moment, with the #MeToo campaign urging women to air their grievances at the same time an anti-Muslim climate makes it hard to speak up.

The activists themselves differ on the best approach, with some pushing to quietly educate communities about the health risks and others ready to name and shame Muslim leaders who fail to fully reject FGM, which right-wing groups falsely portray as part of mainstream Islam. Muslim leaders, meanwhile, say they welcome dialogue but resent the outside agitation on a sensitive issue for a congregation that spans generations and cultural traditions. The factions are talking, but at Dar al-Hijrah, as in Muslim communities throughout the country, the FGM conversation isn’t over. It’s only just beginning.

Given all the taboos involved, FGM isn’t an issue most US Muslim communities address unless they’re forced to.

“If it was up to me, I’d have the imam sit down with five or so survivors and hear the ramifications of these practices,” said 29-year-old FGM survivor Aissata M.B. Camara, whose New York-based nonprofit campaigns against ritual cutting. “If we don’t do these things, I don’t think we can end FGM. We have to break the silence and have these uncomfortable conversations.”

National Muslim leaders condemned Elsayed’s remarks and reiterated that FGM violates Islam’s core tenet of preventing harm. Some women’s advocates demanded his removal. The ordeal wasn’t just a PR nightmare on the outside; internally, a bitter fight unfolded. The imam’s fans made T-shirts proclaiming their support. Critics vowed to leave if he stayed.

After a marathon board meeting, the mosque denounced Elsayed’s remarks but decided to keep him in place, citing his many women supporters. Another imam quit in protest. Elsayed apologized, then walked back his apology at a private gathering where his comments were recorded and leaked. To this day, he publicly endorses a procedure he calls “hoodectomy,” a form of FGM under the UN definition.

In the months since the outcry, Dar al-Hijrah has tried to smooth the tensions, holding town hall meetings and releasing a video that describes the horrors of FGM as experienced by a survivor who attends the mosque. The next step was the women’s conference, where FGM was given time on a health panel despite the risk of a public showdown with critics.

The FGM talk was moderated by Ieasha Prime, an Islamic scholar and women’s program coordinator at Dar al-Hijrah. Prime and the panelists – two Muslim women health experts, one of them an FGM survivor — gave an overview of the practice and the lifelong harm it inflicts. But in Prime’s Q&A, the key dispute was sidestepped: Does the mosque believe there’s a religious argument for any form of genital cutting?

Time ran out before the audience could ask questions. Rumblings rose from the front of the room.

“This is not the conversation we were told we were going to have!” protested Shayma Al-Hanooti, the 30-year-old daughter of a prominent cleric and a critic of the mosque’s handling of the FGM controversy.

Organizers looked pained. Activists, exasperated, clustered on the sidelines. Before emotions could spiral, Prime announced she would give another 10 minutes to FGM, promising to answer questions from the audience.

The women returned to their places for round two.

The World Health Organization says FGM serves no medical purpose and causes harm, including infections, loss of sexual pleasure, childbirth complications, even death.

Though it’s rejected by Islamic authorities and outlawed in many Muslim-majority countries, genital cutting is still practiced by some Muslims in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. In the US, anti-Muslim groups cite FGM to smear Islam and limit Muslim immigration, ignoring the fact that cutting also occurs among Christians, animists, and other groups. The custom endures because of passed-down beliefs about religion, cleanliness, passage into womanhood, or suppressing sexual desires. On Tuesday, activists around the world will mark the UN's International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM with a social media campaign under #EndFGM.

Anti-Muslim groups cite FGM to smear Islam and limit Muslim immigration, ignoring the fact that cutting also occurs among Christians, animists, and other groups.

The most-cited statistics about the prevalence of FGM in the United States are alarming: More than half a million women and girls in the US are at risk for cutting or already have undergone it, according to a 2016 government report.

The problem is, those figures are misleading, with methodology that involves not an actual count but extrapolation based on immigration patterns from countries where FGM is found. Even the study’s authors acknowledge the numbers “do not provide information” on the practice of FGM in the United States.

Nevertheless, right-wing groups use the numbers to hype the threat of girls getting cut in the US, while FGM apologists dismiss the numbers as inflated, saying the practice is a problem exclusive to poor, uneducated immigrants.

Muslim women researchers are at the forefront of new data-collection efforts, but their findings aren’t yet published.

For now, the half-million figure persists in government and news reports, often without the disclaimer. It’s cropped up recently in coverage of a case out of Detroit, the first prosecution under a 1996 federal law criminalizing FGM. The defendants — members of the Dawoodi Bohra subset of Shiite Islam – are mounting a religious freedom defense of their alleged ritual cutting of young girls.

The Justice Department has included the flawed FGM statistics in reports playing up threats posed by immigrants, a move that was welcomed by the anti-Muslim groups having a heyday under the Trump administration.

Stumbling upon an FGM endorsement at Dar al-Hijrah was an Islamophobe’s jackpot. It’s one of the oldest and biggest mosques in the area, drawing more than 1,000 worshippers a day and more than 3,500 for the Friday service. Yet for all its philanthropy and outreach, Dar al-Hijrah is still known for the notorious militants who passed through its doors years ago: al-Qaeda recruiter Anwar Awlaki, who briefly served as imam, two of the 9/11 hijackers, and the Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hasan.

Last May, the press watchdog MEMRI, a right-wing group known for selectively translating extremist Muslim viewpoints, released the video of Elsayed’s FGM lecture from the mosque’s YouTube channel. Muslim women inside and outside Dar al-Hijrah were outraged by the imam’s suggestion that uncut women were likely to become promiscuous, but MEMRI’s role in exposing him complicated their response. Elsayed and his supporters drowned out critical voices by spinning the incident as a “Zionist conspiracy” cooked up by anti-Muslim forces.

While some Dar al-Hijrah leaders privately share the view that Islamic justification exists for a minimal form of female genital cutting, which they compare to male circumcision, they emphasize that it should not be performed on anyone under 18. The mosque’s official stance is zero tolerance for “all forms” of FGM, presumably including the kind Elsayed defends on his personal website. Still, the board decided to let Elsayed stay on after a brief administrative leave, a decision that infuriated anti-FGM activists and made them skeptical about Dar al-Hijrah’s motivations for the women’s conference.

“It’s not even too little, too late — it’s pure PR. It’s damage control,” said Maryum Saifee, an FGM survivor who’s written publicly about her experience. “There’s zero interest in substantively addressing this issue.”

Prime, the women’s program coordinator, dismissed the idea that keeping Elsayed on staff cost Dar al-Hijrah credibility in addressing FGM, and said critics who refuse to engage with the mosque because of him are missing an opportunity. She connects the nascent dialogue on FGM to broader national debates over women’s rights and the #MeToo reckoning, saying tough conversations come with the territory.

“We women will start to have conversations about where we stand,” Prime said. “It became an opportunity to say, ‘Everybody stop, let’s get more educated, let’s build our sisterhood.’”

There’s no mention of female circumcision in the Qur’an.

To Ghada Khan, 43, a public health researcher working on FGM in the Washington area, the overtures sound hollow. Khan said she and other FGM educators have approached Dar al-Hijrah more than once to offer seminars, but the events never materialized because officials insisted that the removal of the clitoral hood or prepuce not be labeled FGM.

“As public health educators and as Muslims who know this is not part of Islam, we could not agree to that,” Khan said.

Instead, the activists organized their own panel last August. The star of that day was Imam Mohamed Magid, one of the nation’s most high-profile Muslim leaders, who showed how proponents of “female circumcision” rely on purported sayings by the Prophet Muhammad that religious authorities deem weak or inauthentic. There’s no mention of female circumcision in the Qur’an.

Magid argued that it shouldn’t even come to digging through religious texts, because the medical evidence of injury and trauma is enough on its own to make FGM incompatible with Islam.

“You should have no argument to try to preserve it. Period,” Magid said to applause from the audience. “It’s been proved beyond doubt the harm of this practice.”

Al-Hanooti, the daughter of the late Mohammed Al-Hanooti, a pillar of Dar al-Hijrah, grew up in the mosque, including four years her family spent in a house on the compound in Falls Church.

Though she’s drifted away since her father’s death in 2015, Al-Hanooti still speaks fondly of the camaraderie and life lessons that came from immersion in what was then a largely poor and immigrant community. That flavor is missing, she said, in suburban mosques that cater to more affluent, acculturated Muslims.

The first time Al-Hanooti returned to the mosque since her father’s funeral was to speak at a town-hall meeting at the height of the FGM scandal. It didn’t go well.

The crowd was mostly men, she said, and no recording devices were allowed. When it was Al-Hanooti’s turn to ask a question, she quoted Elsayed’s remarks and asked how the mosque could continue under such leadership.

“The moment I quoted him, the community went crazy. It was just, like, this eruption,” Al-Hanooti recalled. “I was the only one they cut off, the only one that had a time limit, and suddenly security was in my face.”

One of the security guards who confronted Al-Hanooti at the town hall was working the door for the women’s conference. Al-Hanooti’s friend and fellow activist, 35-year-old Nassiba Benghanem, jokingly asked the man whether he was going to apologize.

“Sister, go inside,” he replied.

The women in the room listened intently to the FGM panel and its awkward encore. When time was up, the FGM crowd wasn’t ready to go. The conversation moved out of the conference room, down the hallway and into coat check, attracting passersby who leaned in to hear.

It was an impassioned but civil exchange, with all the women well versed in the religious, cultural, and medical implications of FGM. The activists were unsparing in their questions; Prime was direct with her replies. Their views overlapped more than they expected. Even so, gaps remained that would require many more hours of talking to bridge, if they could be bridged at all.

Al-Hanooti and the other activists left feeling disappointed, not convinced the mosque was an unequivocal ally in the fight against FGM. Prime said the talks were just a start, establishing the “98.9%” they have in common.

“We’re saying, ‘You know what? We’re not allowing others to dictate our conversation anymore.’ You have a problem with Sheikh Shaker? Okay. He’s not the be-all, end-all of our community,” Prime said. “Come on, women, we have work to do.” ●