The poet Natasha Trethewey and I are sitting at a small table inside of an Evanston, Illinois, restaurant. We are on the campus of Northwestern University, where Trethewey, 52, is the board of trustees professor of English. Outside, fall is beginning to pull itself onto the landscape in all of the most aesthetically pleasing ways. I ask Trethewey what drew her to the Chicago area. She has roots in the south — Gulfport, Mississippi, and New Orleans, specifically — and she spent a good portion of her adult life in the Atlanta area, working at Emory University. “Well, I had ancestors who came up here during the great migration,” she tells me. “Two of my great-uncles and my great-aunt moved here. My mother finished her senior year of high school at Marshall High School.” She pauses for a brief moment, as if she’s considering a different answer, given the makeup of our conversation: two black people who understand movement and migration and the ways our people end up in places that aren’t always our places until they become so. “When I walk around here I have interactions down in the city that feel [like] Mississippi. The way black people are. The way we look at each other and the way we say hello… it’s all very familiar.”

We are tucked away in the corner of this Evanston restaurant because of Trethewey’s most recently published collection of new and selected poems, Monument. The collection was longlisted for this year’s National Book Awards and has served as both a reflection of where Trethewey has been and where she is going. Trethewey is one of America’s most decorated living poets, highlighted by a Pulitzer Prize for her 2007 collection Native Guard and an appointment as US poet laureate from 2012 to 2014. But before approaching her new book, her career, and the line of brilliance she has drawn throughout her time in American Letters, we first focus on the shared monument between us.

When people have a mutual or adjoining grief, I imagine that only the people who share it can see it — like a secret code, or the entry to a hidden door somewhere. Trethewey’s mother, Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough, was murdered in 1985 by her second husband shortly after they divorced. Trethewey was 19 years old. When Trethewey discusses this death with me, she refers to it as “her greatest wound.”

It is the thing that drove her to writing, in the hopes that she might make sense of the trauma, or at the very least so she might be able to use language and grief to hold a nation accountable for its endlessly accumulating sins.

I disclose early on in our conversation that I lost my mother as well. Under different circumstances, I tell her. But I have been visited by that same absence. My hope is that we’ll be more at ease with the understanding that we’ve both longed for a love we don’t have physical access to anymore. I just don’t know how to talk to someone who hasn’t experienced some degree of loss. Upon my disclosure, Trethewey visibly eases a bit. “How old were you?” she asks. When I tell her, she nods slowly. Grief can create a cohort of unbeknownst siblings.

“Almost my brother’s age when we lost my mother.”

“You know, the laureate doesn’t actually have to do anything,” Trethewey tells me in an almost whisper, as if she is revealing a secret of the earth. There is a fundamental misunderstanding of the job, she tells me.

“People always ask me about Obama,” she says, shaking her head. “They don’t know how the laureate is appointed and what it’s appointed to, but remember the whole title is United States Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, so it’s about the libraries. The librarian appoints the laureate, not the president. I was appointed by the 13th librarian, James H. Billington. But I’m glad you asked this because now I can answer for the sake of [current US poet laureate] Tracy K. Smith. I wasn’t appointed by Obama any more than Tracy K. Smith was appointed by Trump.”

Tasked with raising the consciousness of poetry in America, the poet laureate has historically used various techniques to achieve that goal. Trethewey, who served two terms as the 19th poet laureate, from 2012 to 2014, was the first Laureate to take up residence in Washington, DC, starting in January 2013. Trethewey decided that the best use of her time and energy would be to have a presence in the library, drawing people to it and listening to them. She took her inspiration from Gwendolyn Brooks, who served as the final “Consultant to the Library of Congress” (the title poet laureates had before it was changed in 1986) and spent her time there answering every letter she got from school children. “In Washington, people come to do tours and they get as far as the Capitol and stop. They don’t make that extra move to cross the street and go into this great library that belongs to all of the people. So the idea that I could hold office hours and get people into our library to have conversations about poetry during which I could listen to them talk about what was needed in poetry, that seemed like the way to go.”

Before DC, Trethewey had already spent a lifetime moving around, mostly through the American South. Born in Mississippi, her family moved to Canada for her father’s work in 1967. Just a year later, the family returned to Mississippi, and her father got into grad school in New Orleans. Trethewey and her mother split time between Mississippi and New Orleans until her parents divorced and Trethewey moved with her mother to Atlanta. She would spend summers back in Mississippi, but stayed in Georgia until she went to graduate school at Hollins University in Virginia, where her father was a professor.

As with much of Trethewey’s poetry, our conversation returns again and again to parentage and movements across landscapes. Her work is ekphrastic, mapped onto landmarks and statues and pieces of art that might better explain the unevenness of racial history — both America’s and her own. Trethewey writes into the sprawling and untold stories in America’s history, giving voice to the forgotten, or the memories at risk of being forgotten.

“I think one of the hallmarks of Trethewey’s work is its ability to re-inscribe the fact of the black body, a fact American and Southern literary histories need to erase in order to seem much less viciously biased than they have actually been,” says poet Jericho Brown. Trethewey and Brown were colleagues at Emory, but beyond that, Brown has considered her a mentor and friend for nearly two decades now.

“She allows her characters — her own history — to be as complex as history really is.”

When I ask him about Trethewey’s contributions to the black historical narrative in America, he talks about the fullness of her writing and the black people inside of it. “Trethewey’s contribution is that of someone who sees us — she’d say ‘us’ — in individual and human ways and not only representations of resistance. Her black Union soldiers fall in love, her overworked grandmother plays a mischievous trick on a foreman, her black stepfather is a murderer, and her white father who loves her can’t resist microaggressions against her. I mean she allows her characters — her own history — to be as complex as history really is. This makes space for readers like me who are interested in life and not a caricature of life, readers who understand that poems must face us to our good and our evil and our personhood no matter what color we are.”

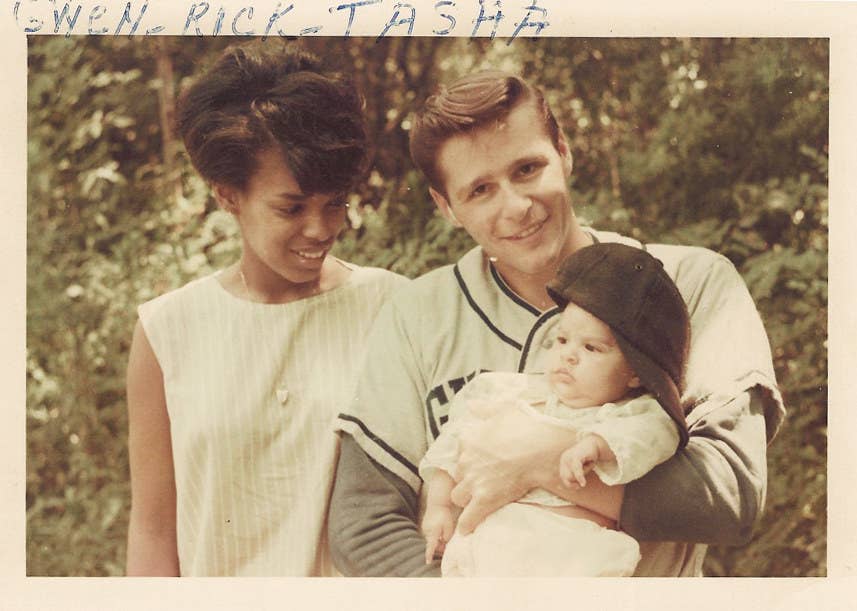

After the sun set on the 2016 election and in the months that followed, there were people who turned to poets for answers, looking for writers — particularly black writers — to “make sense” of how a vague “we” could have ended up here. And so it might seem like the arrival of Monument is perfectly timed, or specific to this moment. This is despite the fact that the collection includes poems that span well over a decade, three presidential administrations, and countless national atrocities, as the collection includes poems from four previous books (Domestic Work, 2000; Bellocq’s Ophelia, 2002; Native Guard, 2006; and Thrall, 2012). The collection also includes new poems, mostly about Trethewey’s relationship with her father, Eric Trethewey, who died in 2014 and was married to her mother illegally at the time of her birth, a year before the Supreme Court passed Loving v. Virginia, which struck down laws banning interracial marriage.

Native Guard honors both Trethewey’s mother and the forgotten racial history of the Civil War. Domestic Work is a book of detailed and beautiful historical monologues. Bellocq’s Ophelia centers on the story of a light-skinned black woman who is a prostitute in New Orleans just before World War I. Thrall is somewhat of a sibling to Native Guard — where Trethewey examines America’s racial stereotypes and confronts her relationship with her father. The sequencing of these books speaks to the growth in Trethewey’s curiosities and her approach to wrestling with the most immense and difficult-to-uproot parts of America. But what stands out beyond that is how many ways Trethewey finds to revisit and restructure history: her own, but also the histories of black people in America.

“You write a book and you hope in some ways that the issues you are trying to deal with in the book will not be as pressing in the moment, that somehow the writing will get us beyond a certain place,” Trethewey tells me. “But what I felt is that in these last 12 years, both with Native Guard and particularly with Thrall, I was trying to write about deeply ingrained and unexamined notions of racial difference and racial hierarchy. Going from the enlightenment and forming the basis of contemporary white supremacy. I didn’t expect to see forms of racial hierarchy and ideas about white supremacy reemerge in such a virulent way. I didn’t expect to see the debates around Confederate monuments and historical memory around the Civil War to come back in such a troubling and often violent confrontational way, and yet here we are.”

Monument acts as a mid-career retrospective, as a new and selected collection can, particularly for a poet like Trethewey, who has had a prolific and highly visible career, but who has also been committed to stylistic shifts with each project. The book’s title is a tribute to many things, both the immovability of America’s obsession with monuments and the task of building and rebuilding one’s self in an attempt to obscure grief.

Trethewey’s house burned down almost a year ago on Thanksgiving, shortly after she moved to Evanston. For someone whose work is so rooted in the restructuring of memories, I wondered aloud what it must have been like to watch tangible items whisked away in an instant.

“Well, we made the choice to buy an old house and…well…you know people have made all kinds of questionable decisions over the years,” she says with a sigh. For a brief moment, I am unsure if she is talking about the decision to buy the house or the ghostly residue of lives lived in the home before them.

“It had been a rocky purchase, and the people who we bought it from were kinda mean, and you don’t know what spirits a 120-year-old house is going to have, but I felt good in it,” she tells me before stopping for a moment. “My father’s ashes were up on the third floor with me, and I was sorta looking forward to scattering a little there just to own the house even more.”

There was a miracle in all of this, though. Trethewey tells me that despite the loss of 80% of her and her husband’s things, their books survived. “The books were packed so tightly on the shelves that no air could get between them,” she says. Letters written by her parents and her father’s old books were also spared, save for some water damage.

Even with two floors of the house damaged by the fire, the couple chose to stay and rebuild. I ask Trethewey about her choice to stay. “I was thinking to myself, How am I going to live in this house that has done this thing to us?” she tells me. “And then not long after, I began to see that it was a kind of cleansing. The house burned everything that needed to go and now we get to put a new history in it. A new monument to us and to our family. It feels like a sort of second Jesus year for me. I use that phrase in a poem, ‘Miscegenation,’ but this is the 33rd year that I’ve lived without my mother, and so it felt like those 33 more years and now another sort of trauma. And if I’ve learned anything from the last 33 years, it’s about not only living in the state of bereavement but also about resilience.”

“I certainly don’t sit down with this idea like I’m going to write for social justice. I hope that sometimes it can be an outcome.”

Her use of history as a driving force behind her poetry and as a nudge toward enlightenment — for herself and others — feels rooted in a type of empathy. Throughout this vast catalog of work, teeming with references to specific dates or old photos, Trethewey doesn’t shame readers for what they don’t know. Instead, she invites them to learn alongside her. For example, the poem “The Americans,” originally published in 2012’s Thrall, is a piece dissecting race and its importance in American history. The poem is in three parts, each of them using a different image or piece of writing as an anchor. Part one reworks language from 1800s Mississippi physician Dr. Samuel Adolphus Cartwright’s writings on “the white negro.” Part two is inspired by “The Quadroon,” a painting by the 19th-century artist George Fuller. And part three draws its themes from the photo “The Americans” by photographer Robert Frank. She is rigorous about research, and unafraid to let that show up in the finished product; in her poems, the speaker is also saying, “I did not know this once, before I became fascinated by it.”

I ask Trethewey if, in order to honor the history of black people in America, there also has to be a correction of the historical record and if work leaning toward correction — even in its most affectionate moments toward its subjects — is sustainable.

“One of the [Robert] Hayden quotes I go back to all along is how he says he wrote in order to correct the misapprehensions in African American history,” she says. “But I agree with you that it’s not simply about correction, sometimes it’s simply about truth-telling around it. In my home state, you hear a lot about other places that can do truth and reconciliation commissions. In the state of Mississippi, there’s a truth commission, just truth because we can’t even get to reconciliation yet. To inscribe what has been erased or left out is a correction. I think about Seamus Heaney’s idea of redress in a poem that poets don’t have to be aiming at social justice when they sit down to write, but it can be an outcome. I certainly don’t sit down with this idea like I’m going to write for social justice. I hope that sometimes it can be an outcome.”

When I ask Brown about Trethewey’s legacy, he offers an insight: that she will perhaps be remembered in two ways, depending on who is doing the remembering. “For poets, she’ll be remembered for her deft use of subtlety, for her use of forms that make ironic the subjects they hold, for her very interesting way of interweaving personal history and public history — their impact on each other — in a single book. And for critics and other readers, I think she’ll be remembered for the ways that the poems are all-out acts of resistance and anger. There always seems to me something seething between the lines of every Natasha Trethewey poem, which is part of what makes her work so admirable and so completely impossible to imitate.”

There is something about the anger and disgust in her poems that has to be a part of her legacy as well, Brown insists. It is a feature of the work’s interior that, perhaps, won’t be fully appreciated until the writer is not present.

“I don’t think we connect her as a person to that anger because she is with us and laughs and supports and is a part of the larger poetry community that thinks of her as an accessible past poet laureate. But maybe when she’s gone, it will help move us past her celebrity into a real look at just how disgusted the poems are and how their subtleties are a feature of their clapback, their shade, their exasperation. These are some of the things that actually last forever in literature.”

Trethewey grapples with the country’s history, but the loss of her mother and the tenuous relationship she had with her father is always at the center of her work. When I mention that Native Guard and Thrall seem to speak to each other, Trethewey issues a small corrective.

“Let me say I see Native Guard and Thrall as really different,” she says, gently. “I think people could read Native Guard, you know people who can think of themselves as good liberals could read a book like that and go, ‘Oh yeah, wasn’t that so horrible, what happened all that time ago?’ or even in this civilized era, wasn’t that awful? Wasn’t Jim Crow awful? Wasn’t what happened in Mississippi, wasn’t that awful? We are so much different than that. They can imagine themselves always on the right side of history. It’s easy to forget, you know, where they might have been positioned before, but now everyone can think of themselves on the right side of history. When I wrote Thrall, because it was an intimate conversation with my father in—”

She pauses here and exhales heavily, as if preparing to remove a bandage covering a wound.

“I wanted to talk about why it was that my beloved father who loved me dearly could still harbor these deeply ingrained and unexamined notions of racial difference and hierarchy. How could he both love me but also think that his contribution to my being — whiteness — was an improvement? What does that say about what he thought about my mother and my grandmother and all the people that I think of as my people?”

Of her books, Thrall is the one that finds Trethewey in a state that seems most worried about what her curiosities might unearth. Almost everything the speaker looks at in the book is a reminder of not only parental lineage, but the fractures of her specific parental lineage. The title poem of the book opens with the lines:

He was not my father / though he might have been / I came to him / the mulatto son of a slave woman / just that / as if / it took only my mother / to make me / a mulatto.

The poem is written in the voice of late-1600s Spanish painter Juan de Pareja, but the work of the book is about this: history echoing into the present lived experience. “I was writing about trying to look across time and space, where these ideas about race come from,” Trethewey tells me. “How we’ve inherited it such that it is in everything, in the air that we breathe, but in order to do that I learned to look very closely at my own family and at my own father. When I read from that book and I come up and talk to people afterwards, it’s often older, white people who come up to me and they’re weeping because all of a sudden for a few minutes they’ve had to interrogate their own sense of difference and hierarchy that they’ve not thought they had before.”

I ask Trethewey what is to be gained from this repetitive hammering away at the towering and inflexible imagination of racial dominance in America, what the possible aim could be after all this time.

She pauses a mug of newly warmed coffee halfway to her mouth, and gives a chilling, measured response.

“I want people to have a deep and personal reckoning. One by one.”

So much of my conversation with Trethewey is weighted by grief. During a particularly emotional retelling of a story about her mother, Tretheway stops and apologizes for the emotional shift. She asks if it’s ever like this for me, and by “this” she means do I find that some days are even harder than others to speak the name of someone you love into the air knowing that you will never see them again. I tell her a story of driving past a field of my mother’s favorite flower last spring and how I had to pull over because I began crying so much that the road in front of me became a single blur of darkness. She nods and continues.

“I’ve been working on a memoir about my greatest existential wound,” she answers when I ask about some of the new work that appears at the end of Monument. “I wrote this poem after jogging through a graveyard, a Confederate cemetery, and thinking I’ve been doing all this research about Union soldiers. Maybe I should write a poem about historical memory because I’m in this place, but when I got home, the poem that came out was about the day we buried my mother, and that’s when it hit me that there was no monument on her grave, so what she had in common was the same with these black soldiers.”

Trethewey continues, seemingly emotionally spent by the recall of the memory, but driving toward a point. “What I didn’t understand until working on this memoir was that my mother was murdered on Memorial Drive and Memorial Drive runs from downtown Atlanta up to Stone Mountain, the world’s largest monument to the Confederacy. She was murdered right there in the shadow of this great, big rock that remembers one history and erases others, and so it just felt so small, her death there unremembered and this huge monument to this very troubling history. I’d be trying to write the prose and a poem would need to come out instead.”

I want to ask a foolish question about happiness and joy; I am sitting across from a poet who has been decorated and rewarded greatly for doing immensely difficult work that a lot of other people — poets or not — don’t want any part of, at least not with the consistency and ferocity that Trethewey has taken to it. I ask what it must be like to have work that is so richly celebrated, but that cannot be removed from grief.

“Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote that poems are the records of the best and happiest times in the happiest and best minds,” she says, smiling faintly. “The making of a poem is just that for me. Even when I’m writing about something traumatic, I’m always really happy, so every poem is also a celebration.”

When I ask where her happiness comes from, Trethewey looks briefly incredulous, as if I haven’t been hearing her this whole time.

“Resilience. I could have easily been destroyed.”

She pauses long enough for me to almost ask something new, but then reenters the thought.

“I could have easily been destroyed, and not only am I not destroyed, one might argue that it’s not just that I’ve survived, but that I’ve thrived. That out of the ruin of my mother’s life I forged my own. She gave that to me. If the religious faithful believes that Jesus did that for them, I believe my mother did that for me.”

This is a black woman who has committed an entire life and career to holding a country accountable, despite the weight of her own grief. I thought of how black women are seen as calmers and soothsayers, answerers of all questions and bringers of all solutions. It seems almost immediately unfair, as our interview winds down and I find myself sitting with the enormity of our conversation, the monument we’d built together. In an instant, before I could stop myself, I ask:

“Do you know that you are not responsible for the country?”

“I feel very responsible,” Trethewey says immediately, not angrily, but confidently. “I have to do this work so that my mother did not die in vain. I feel responsible for trying to have a nation where everybody gets to live up to their potential safely. If not, then my mother’s death is meaningless.”

That we both know this isn’t true doesn’t seem to matter. ●

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic from Columbus, Ohio. He is the author of The Crown Ain’t Worth Much (Button Poetry/Exploding Pinecone Press, 2016), nominated for a Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (Two Dollar Radio, 2017). He is the author of the forthcoming book about A Tribe Called Quest called Go Ahead in the Rain (University of Texas Press, February 2019), a poetry collection called A Fortune for Your Disaster (Tin House, 2019) and a history of Black performance in the United States titled They Don’t Dance No Mo’ (Random House, 2020).