In most eulogies of the director John Singleton, Boyz n the Hood will likely be examined and spoken of with all the praise it deserves, and hopefully more. There is nothing I can say about that film that won’t be said better by someone else who was old enough to live through its debut.

So instead, I want to talk about Rosewood, Singleton’s 1997 historical drama based on true events. It was the first film of his that attempted a retelling of American history — a notable departure from 1993’s Poetic Justice and 1995’s Higher Learning, his two films after Boyz, which continued to explore contemporary black life, black love, and black joys and anxieties.

Here’s the real-life version: During the first week of January 1923, the town of Rosewood, Florida, was destroyed. Situated on a railway along the Florida seaboard, Rosewood was primarily black and working class. Shortly before the massacre, a white woman from a nearby town claimed a Rosewood resident had raped her. Despite no evidence, that resident was found and then lynched. A mob of more than 100 (mostly white) men began roaming the outskirts of Rosewood. As black residents attempted to arm themselves and prepare to defend their land, they were quickly overwhelmed and overrun by the violence of the white mob. The town was burned to the ground. The official death toll was eight: six black residents, and two from the white mob. The black survivors of the Rosewood massacre hid in swamps for days until the mob moved on, then they evacuated to new cities. No one ever returned to Rosewood. The town, cloaked in smoke and rubble and then nothing at all, ceased to exist.

Singleton’s retelling of Rosewood hones in on the lives of specific characters, caught up in a whirlwind of racial and romantic conflicts. But the history of the story remains. There is a riot brought on by a woman who — at least in the film — explicitly lies about her relationship to a black man. There is a massacre and an attempted rescue mission. There is a town, and then not.

Rosewood is a spectacular film that — like many of Singleton’s efforts — defines the level of emotional intensity early, and then maintains that level the entire time. Also, like many of Singleton’s efforts, it doesn’t offer a solution for the whirlwind of peril or violence, just the reality of its aftermath.

I had never heard of the town of Rosewood when I stumbled across Singleton’s film in 1999, two years after it was released. When watching it, I didn’t even realize the film was a historical account of anything. Young, overly optimistic, and foolish, I thought there was no way a town of black people could just be wiped out, and no one would know about it or talk about it or shout about it every single day of their lives.

Like many of Singleton’s efforts, Rosewood doesn’t offer a solution for the whirlwind of peril or violence, just the reality of its aftermath.

The film was critically adored but a commercial failure. In talks about Singleton’s body of work, it is often the movie that gets left out. But it is an invisible bridge from his three early commercial triumphs to his later-career work, which were action films: a 2000 remake of Shaft. A Fast And Furious sequel in 2003. The still-thrilling Four Brothers in 2005.

If I am to talk about the legacy of any storyteller, particularly a black storyteller, I have to think first of what they were able to breathe new life back into, and who got to benefit from that new life. Singleton made a movie about a disappeared town and in doing so briefly gave a generation a window into a history tucked under so many other American histories. To make films about the dangers of contemporary black life is one part of the story. Another part is to make films about the history of those dangers, or films that show the dangers as not strictly new.

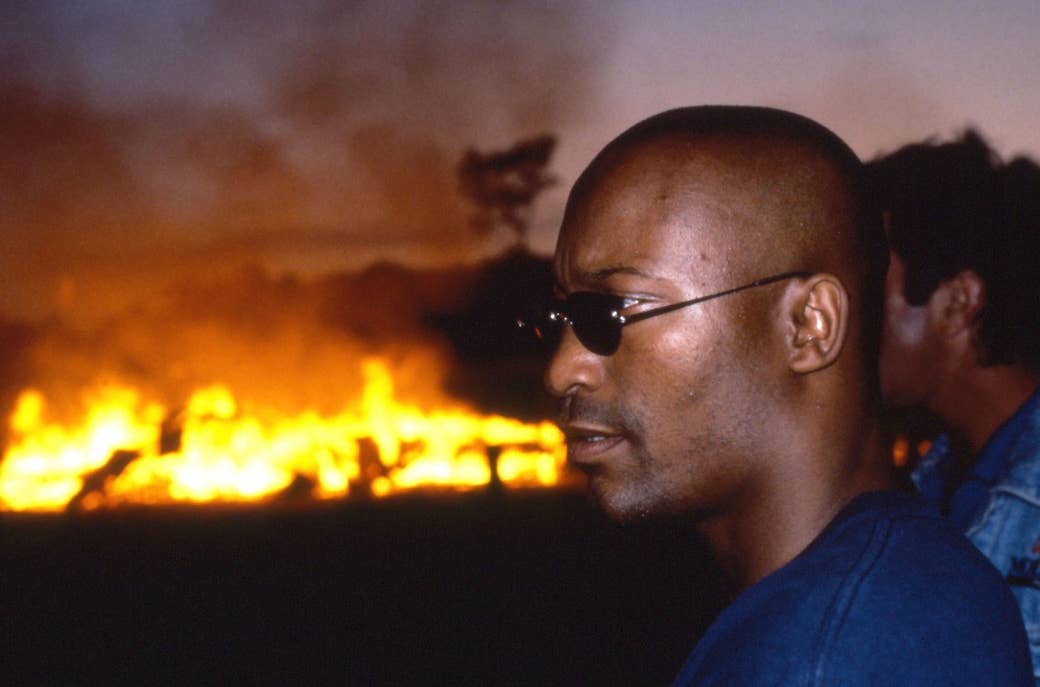

America is a country obsessed with neatly forgetting its past, and Rosewood was a film eager to force remembrance. In many of his films, but particularly in Rosewood, Singleton chose to see black people as more than just victims of violence, or capable of carrying out violence. Rosewood becomes a town worth mourning by the film’s end because of how Singleton depicts the lives of the people in the town before the violence finds them. At its heart, Rosewood is a love story, between two of its main characters (Ving Rhames’ Mann and Elise Neal’s Beulah), but also a love story about people who didn’t have much, fighting to keep what they gained. I appreciated Rosewood for this, and still do. No one saw it, I imagine, because no one wanted to see it. It is easier to imagine that story is just too impossible to be real.

America is a country obsessed with neatly forgetting its past, and Rosewood was a film eager to force remembrance.

Black people with every right to be cynical often get asked about hope. I see this question in interviews, and I’ve also been asked about it during Q&As, usually by some person who is searching for one of us to give them something to be hopeful about — an answer to the world’s drowning or its political unraveling. I can’t speak for everyone else, but I’ve long decided that I am not propelled forward by ideas of hope, as much as I am by honesty.

If hope is a gift at the end of a long and honest road, then I’ll take it. But I’m not particularly counting on it. Sometimes, the reward for survival is the opportunity to survive. I like to think of the work that Singleton gave us much like this, particularly his early movies. A laying out of difficult stories with difficult truths, and at the end, a shrug, or an understanding that even if this isn’t what you came for, it’s what you’ve got. And in that way, he made dangerous films. He made films that asked me to reckon with my ideas of neatness and conclusions and love and loss. When the screen goes dark, we are only left with ourselves, who watched and took something away or left something behind.

Sometimes, there are buildings burned down that no one rebuilds. Sometimes, there are dead bodies and no funerals, or no grave markers with names on them. And sometimes, proud people are run out of a place they loved because they couldn’t fight anymore, and that doesn’t make them any less proud. I think, today, of the moments I sat on the floor of my childhood home after Rosewood finished. The world outside I thought I knew had shifted. The fact that John Singleton gave me that opportunity, even once, is worthy of the highest praise. ●

Hanif Abdurraqib is a writer from the East Side of Columbus, Ohio.