If you aren’t a lawyer, you may be surprised to learn that much of the country’s legal rulings aren’t freely accessible to the public, despite the crucial role many played in the shaping and organization of American society. While the documents are part of the public domain, a byzantine patchwork of outdated government interfaces and expensive paywalls restrict access to them.

Now, as part of an ambitious multiyear project, Harvard University is liberating that information. Home to the country’s most comprehensive collection of U.S. case law, second only to the Library of Congress, Harvard is partnering with technology startup Ravel Law to digitize its legal library — more than 200 years' worth of cases — making it fully and freely searchable.

“Driving this effort is a shared belief that the law should be free and open to all," said Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow. "Using technology to create broad access to legal information will help create a more transparent and more just legal system."

A team of seven digitization specialists working full-time at Harvard’s library will dismember more than 40,000 physical books, preparing them for their digital afterlife. They will use blades to cut off the books’ spines and then feed the loose pages of court decisions, about 40 million of them, into a massive, 12-foot high-speed scanner. But digitizing these books is just the beginning.

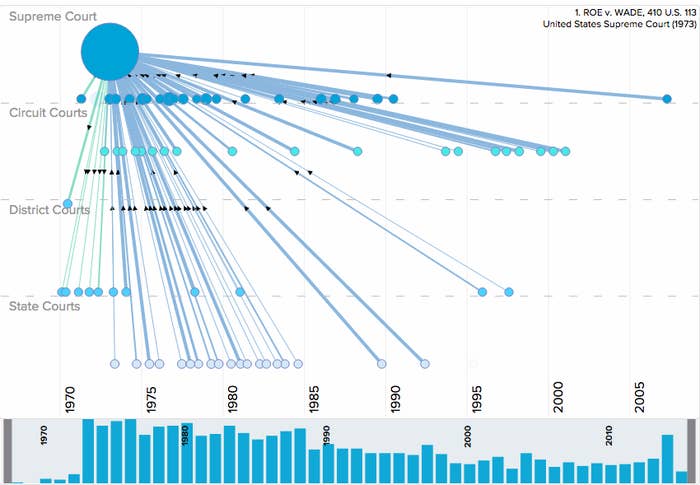

After the material is scanned and converted into machine-readable files, Ravel will render the legal research fully searchable. The company, founded by two Stanford law school graduates, plans to enhance the new database by building intuitive, analytical tools for the public and professionals to use, like mapping connected cases visually, and sussing out patterns throughout legal history.

Ravel will fund the “Free the Law” project. The company doesn’t yet have an estimate for its total cost; it’s contributed $1 million so far.

“Legal information should be freely and publicly available,” Daniel Lewis, co-founder and chief executive officer of Ravel, told BuzzFeed News. “We can combine the digitized Harvard collection with advanced tools that will be useful for professionals, but also for the general public.”

Subscriptions for the dominant legal research databases, LexisNexis and Westlaw, can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, sometimes millions, depending on the size of the law firm. Ravel aims to offer up the massive store of legal information to the public but also to provide greater value to small firms with limited resources and large firms looking for a competitive edge. While Ravel’s search function will be free to use, it charges for subscriptions to its suite of analytical tools, which will soon be augmented by data from Harvard’s library.

“Not only will the law become accessible, but all sorts of interesting things might be done with it as a database,” Jonathan Zittrain, a Harvard law professor and director of the law library, told BuzzFeed News. “To me it’s kind of like seeing Google Maps for the first time after having only used MapQuest,” he said, referring to new, possible insights a user might glean from analyzing and visualizing case law.

Ravel will also open up its trove of information to scholars and nonprofits who wish to experiment with the data and develop novel tools and research projects. “I see this form of digital transcription as a way of making opportunities for new forms of search that may unearth relationships between cases that weren’t apparent before,” Zittrain said.

Like his partners at Ravel, Zittrain views the Free the Law initiative as a means to bypass the high cost of gaining access to legal material and put Harvard’s unmatched collection in the hands of anyone with an internet connection.

“It’s one thing just to access it in a book. It’s another to be able to build relationships among cases because nobody reads the law from cover to cover starting with the first book.”

Zittrain said he was impressed by Ravel’s visualization techniques and the company’s commitment to creating an open platform for future research. While Harvard and Google have previously partnered in a book scanning project, Zittrain said he believes the search giant is not particularly interested in this type of public access digitization effort. He also noted that Google’s advertising model is an imperfect fit for free legal research. As part of its agreement with Harvard, Ravel will make the university’s law database available to other commercial entities at no charge after eight years.

Said Zittrain, “At a time when there is some concern that the organic web is shrinking, that more and more information is not being put up on a website but being shoved into an app — and there’s no way to search easily across apps — this is a good step in the opposite direction, in more openness.”

Thumbnail image: Lorin Granger, Harvard Law School