Legislators pushing to have backdoors built into our smartphones by default have a new rhetorical boogeyman with which to herd public opinion: human traffickers.

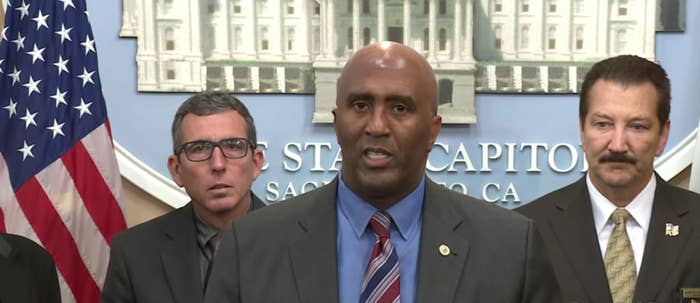

California assemblymember Jim Cooper introduced legislation earlier this week that would compel smartphone manufacturers in the state to weaken their encryption standards to provide special access to law enforcement.

Cooper, a 30-year veteran of the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department, views end-to-end encryption as a shield for human traffickers, one that prevents law enforcement from gathering crucial evidence.

“Full-disk encrypted operating systems provide criminals an invaluable tool to prey on women, children, and threaten our freedoms while making the legal process of judicial court orders useless,” Cooper said during a press conference Wednesday.

Cooper’s bill would force manufacturers of iOS and Android devices to design their products so that they can be unlocked and decrypted. The law would take effect in 2017. And sellers who fail to comply could be fined up to $2,500 per device.

In the aftermath of the Paris and San Bernardino terrorist attacks, the popularity of strong encryption tools has drawn the scrutiny of concerned lawmakers, reigniting a national policy debate pitting law enforcement officials against Silicon Valley.

Privacy advocates, computer scientists, and technology companies maintain that efforts to weaken encryption standards overlook the benefits that secure communications provide. In turn, law enforcement officials, led by FBI Director James Comey, insist that so called “warrant proof” encryption offers criminals an escape from the reach of the law.

Last year, the Obama administration declined to pursue legislation that would force tech companies to alter their encryption products. While some members of Congress are eager to discuss the issue, new federal encryption policy has gained little traction. Cooper’s bill brings the encryption debate to the state level with a new focus: Instead of terrorism, its conceit is the fight against sex trafficking.

Jenny Williamson, the CEO of Courage Worldwide, an organization that provides homes for people rescued from human trafficking, said that encrypted phones can hold evidence that supports the testimony of victims and help prosecute suspects in court. “If our law enforcement partners have that evidence maybe, just, maybe, we don’t have to put [victims] on the stand,” Williamson said during the same press conference. “Maybe they won’t need [that] testimony if they have the evidence that’s in a phone.”

Anticipating the privacy and civil liberties criticism aimed at federal law enforcement officials, Cooper said his proposal targets only those who deserve government suspicion. “It’s not the boogeyman, it’s not NSA, it’s not Edward Snowden,” he said. “Ninety-nine percent of the public will never have their phone searched with a court order. We are talking about folks who are involved with human trafficking.”

The California bill outlawing strong encryption on consumer devices mirrors another in New York. Backed by Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance — an outspoken critic of the tech industry and its commitment to encryption — the bill would fine New York retailers who sell devices that cannot be decrypted by law enforcement.

In perhaps his most controversial statements, California’s Cooper framed his bill as a way to “put the responsibility on the tech industry. That’s what it comes down to: people over profits.”