As politicians in New York and California take aim at the kind of strong encryption built into Apple and Samsung mobile devices, lawmakers in Washington believe it should remain a federal issue, to be discussed and settled by Congress.

Rep. Ted Lieu, a Democrat from California, intends to unveil new legislation Wednesday that would block states from imposing rules altering or weakening encryption products sold to consumers.

Co-sponsored by Texas Republican Blake Farenthold, the bill seeks to preempt state and local governments from passing encryption laws that would limit the type of security software phone manufacturers can sell. The proposed legislation relies on the Constitution’s "commerce clause," which grants Congress the power to regulate interstate commerce.

Rep. Blake Farenthold, at left, and Ted Lieu, at right.

"I want to stop states from mandating encryption backdoors in consumer products," Lieu told BuzzFeed News. "That would result in a patchwork of completely unworkable laws — you can’t have Apple and Google make a smartphone just for California and New York, and then a different won for Ohio and Tennessee.”

Lieu’s bill takes aim at two proposals working their way through the state legislatures in Sacramento and Albany, where lawmakers are pressuring phone manufacturers to design security systems that can be unlocked by law enforcement.

Opponents of altering encryption standards view such initiatives as dangerous "backdoors" that weaken security and privacy. Law enforcement officials, however, argue that encrypted phones interfere with their duties, offering criminals a tool to conspire and conceal evidence beyond their reach.

Messages protected by end-to-end encryption can be read only by the people communicating — no eavesdroppers can listen in. Not even the technology companies who create and service encrypted phones can access secure data. Law enforcement officials believe this arrangement threatens national security, since, even with a judge’s permission, investigators are prevented from accessing encrypted information.

At a Senate hearing Tuesday, FBI Director James Comey noted that it’s the investigations of local police that suffer the most due to the mass-adoption of encrypted devices.

"It affects cops and prosecutors and sheriffs and detectives trying to make murder cases, car accident cases, kidnapping cases, drug cases," he said. "It has an impact on our national security work, but overwhelmingly, this is a problem that local law enforcement sees."

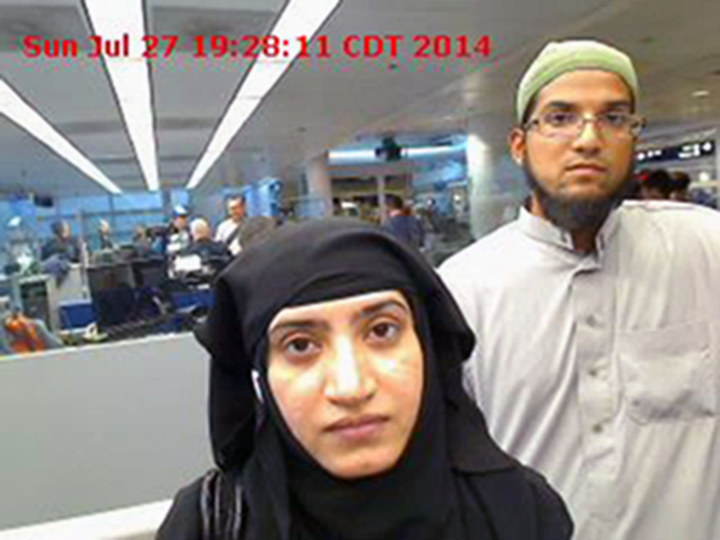

Case in point: More than two months after Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik killed 14 people in an apparent ISIS-inspired attack in San Bernardino, Comey said his investigators still have not managed to unlock one of their phones.

Comey has not publicly pushed for legislation forcing companies to design special government access into their devices, but he has pressured Silicon Valley to voluntarily provide encryption that can be decoded by law enforcement.

Lieu, however, disagreed with Comey’s assessment. While the congressman acknowledged encryption poses a challenge for law enforcement, he believes it ultimately protects consumers and the public.

"There are lots of things that make law enforcement difficult," said Lieu, who opposes any plans to impose federal standards on encryption. "One of them is paper shredders. You can destroy a lot of evidence with paper shredders. But guess what? Paper shredders also protect our privacy. The same with encryption."