More than 700,000 Australians are living with endometriosis. Cells similar to those that line the uterus are growing in other parts of their bodies, usually around the pelvis, and sometimes in tissues and organs outside it. The disease can lead to debilitating long-term chronic pain, compromised fertility and sexual dysfunction.

The federal government’s National Action Plan for Endometriosis, released in July last year, acknowledges endometriosis is “chronic”, “common”, “frequently under-recognised” and that it impacts the “social and economic participation, physiological, mental and psychosocial health of those affected”.

The plan refers to research that indicates the condition could be more common than breast cancer and diabetes for women aged 15 to 49 and costs Australian society $7.7 billion each year — two-thirds from lost productivity and the rest from direct healthcare costs.

There’s a debate among clinicians and those living with endometriosis as to whether the government’s Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) review, specifically recommendations made by its gynaecology committee, would increase the costs of laparoscopies, which are crucial to diagnosing and treating the condition.

Private gynaecologists told the Sydney Morning Herald the cost of the operation could increase by as much as 20%, but a spokesperson for health minister Greg Hunt told BuzzFeed News the government was “always looking to do more for women affected by endometriosis” and that the minister would have more to say on this “in the very near future”.

“The government would not under any circumstances contemplate higher out of pocket costs and nor do we see the committee as recommending that,” the spokesperson said.

Co-founder of health promotion charity EndoActive, Syl Freedman, was on the steering committee for the national plan and said any cost increase would be “awful for patients”.

“We really hope that any recommendations by the [MBS] review committee won’t incur extra costs for endo patients,” Freedman told BuzzFeed News.

“It is very, very expensive to live with a chronic illness and taking out the obvious costs of surgery and prescriptions and over the counter medication and pain relief, there are complementary therapies so things like pelvic floor physio, acupuncture, seeing a naturopath or dietician or gastroenterologist.”

Freedman, who lives with endometriosis, said there were also costs associated with loss of productivity.

“We already know that there are people with endo who are on the disability pension because they can’t work,” she said. “The existing costs of living with a chronic illness is a devastating burden for women with endometriosis and their families and any additional costs could really make or break a situation for a lot of people.”

BuzzFeed News spoke to five women about what they spend to manage their endometriosis.

It took a decade of pain and an emergency surgery before Melbourne lawyer Gemma Cafarella was finally diagnosed with a condition she long believed she had.

“I had complained of endometriosis-like pain since I was 18 to GPs and I wasn’t actually diagnosed until I was hospitalised for burst ovarian cysts when I was 28,” the now 31-year-old told BuzzFeed News.

“They did it all at once and removed the endometriosis and a couple of cysts so when I woke up I found out that I’d been formally diagnosed.

“For 10 years I’d been saying I could have endometriosis but was told my period cycle wasn’t consistent with someone who had endo, which I now know to be completely irrelevant, so by the time the [cysts burst] I was in around the clock pain.”

Cafarella sees her GP on average once a month, a private gynaecologist multiple times a year and a range of private specialists to treat complications caused by her endometriosis.

She occasionally sees a specialist gynaecologist physiotherapist where the initial session was $170 and the subsequent sessions are $120.

“The recommendation is that I do a course of six or eight sessions and these have no rebates, it is all privately paid for,” she said.

Cafarella has also seen a gastroenterologist for $170 due to complications from her first surgery: “I was then diagnosed with a potential bladder complication where one urologist thinks the endometriosis is actually growing outside of my bladder.”

When Cafarella sought a second opinion from another urologist, she was told she needed $1,500 worth of treatment for interstitial cystitis, a chronic bladder condition.

“He laughed when I asked if there were any [public system] options,” she said.

She does not have private health insurance and believes in universal healthcare.

“I want to pay the additional tax and I want that to be put into the healthcare system and I want to be contributing for other people who can’t afford to,” she said.

Any increase in the the cost of laparoscopy would be “gutting”, she said.

“The laparoscopy was free and I can’t tell you how grateful I was that it was free,” she said. “It has been the one piece of optimism in the whole thing that I feel so glad we have universal healthcare service that covers us for that operation, even if it takes a while to get in.”

Increase in surgery fees could mean a postponed diagnosis for women with a disease Cafarella said was “very much diagnosable”.

“There are years of delay for women between first complaining of symptoms and being diagnosed and that can be a decade of treatable pain and feeling crazy.”

For three years Cafarella saw an acupuncturist once a month at $60 a session.

“It sounds very indulgent but I occasionally do go and have a massage because when you’re feeling so miserable and you’re in so much pain, it does feel necessary,” she said.

Cafarella has also been referred to a psychologist who specialises in assisting clients dealing with chronic pain.

“I get a rebate on 10 sessions a year but I see her roughly once a fortnight,” she said.

As a lawyer, Cafarella doesn’t have much say over when she has to be in court.

“You have to turn up on a particular day at a particular time and I just do so in quite significant pain,” she said. “[Endometriosis] uses up most of my sick leave so I worry about running out if I get a bad cold in winter.”

She is concerned about the "stigma of being unwell" and of being perceived as weak by her colleagues, but about once a month Cafarella has to get an Uber home early to lie down.

"I have a friend who has endo who pretends to get random illnesses each month so that they don’t have to come out as a person with a chronic illness”.

Jennifer Doherty wasn’t diagnosed with endometriosis until she was 27, despite ongoing symptoms and fertility issues.

“My first laparoscopy took six hours and [my surgeon] said it was one of the worst cases he’d ever seen,” the now 39-year-old told BuzzFeed News. “That was my first of four laparoscopies.”

She has done five cycles of intrauterine insemination (IUI) and four rounds of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Two years ago she decided, with her partner, to stop trying.

In November last year, Doherty had a complete hysterectomy and both of her ovaries removed: “It has only been three months but knowing that I’ll never have to have another period is massive for me.”

Doherty has private health insurance but estimates for all her treatment, including her hysterectomy, she is $15,000 out of pocket, plus she has spent $30,000 on related treatments.

“Luckily with private health insurance, most of what I’ve had to spend has been covered, but that is $400 for my partner and me until we removed pregnancy from our cover, and now it is $300 a month,” she said.

Throughout her 20s Doherty found it hard to hold down a job because she was constantly having time off.

“I’ve been with my current company for over 10 years and they have been really understanding,” she said. “I never have any sick leave or annual leave and I’m constantly having to take unpaid days off too, so it means if something else goes wrong I don’t have leave.”

Last year Doherty was in hospital for a week for a back injury and had to take unpaid leave. She said laparoscopies should stay affordable because they are the “gold standard for detecting endometriosis”.

Brisbane woman Lacee Overton’s periods had been getting progressively more painful for a decade.

“Then eventually not only was I having pain associated with my period but I was having pain all day, every day and I was getting really bad migraines and restless leg syndrome and stomach problems,” the 31-year-old told BuzzFeed News. “I felt generally awful and I would do my best to carry on when I was at work and go to the gym.”

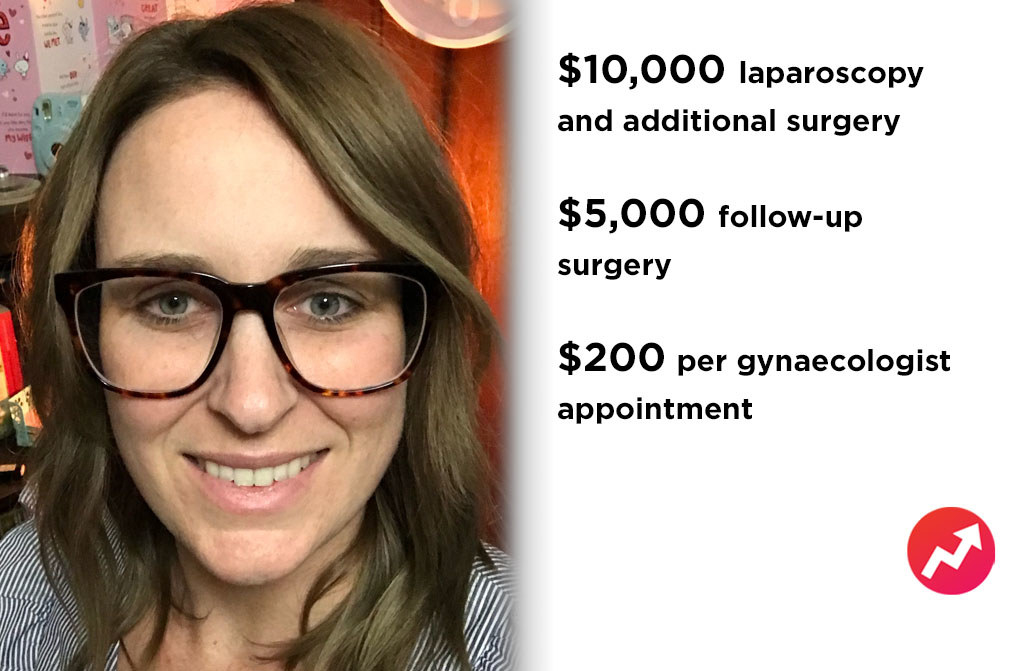

In February last year Overton had a laparoscopy at a private hospital.

“That was the biggest cost for me because I thought the majority of it would be covered by private health, but the day before I was going in to the surgery I found it wasn’t covered and I had to pay surgeon fees, a night at the hospital, the anesthetist, the assistant and they actually had a second surgeon because my endo was so severe and might have been wrapped around my bowel,” Overton said. “All up it was $10,000.”

She saw a gynaecologist before and after that surgery for $200 per appointment.

“Then I had to have a second surgery because I’ve had endo for so long it had been growing about a decade … that was a day procedure which cost about $5,000,” she said.

Overton didn’t want to go on the waiting list for the public system.

“I had such a severe case and I wanted to make sure I was seeing someone who was highly recognised for handling my level of endometriosis,” she said. “It was definitely a big blow out to shell out around $15,000 in the span of two months. That has probably kept my husband and I from buying our first home.”

Overton, a sales account manager, said she is a “high functioning person” but found the condition “challenging and upsetting”.

“When I’m client-facing I need to be 100% on and if I’m having a day when, to be graphic, I’ve got blood running down my leg and I’m in so much pain I want to cry, I still have to go out and talk to a client,” she said. “It plays on your mental health and it is hard to try and remain happy and not just go ‘well I don’t want to get out of bed and I don’t want to see people’.”

Overton said she has avoided having to see a psychologist because her two best friends have endometriosis and she relies on their support.

“I can pick up the phone or send a text message and say ‘hey I’m having a really terrible day’ and they understand,” she said. “I am lucky in that I have support in those girls that I haven’t reached out to a professional.”

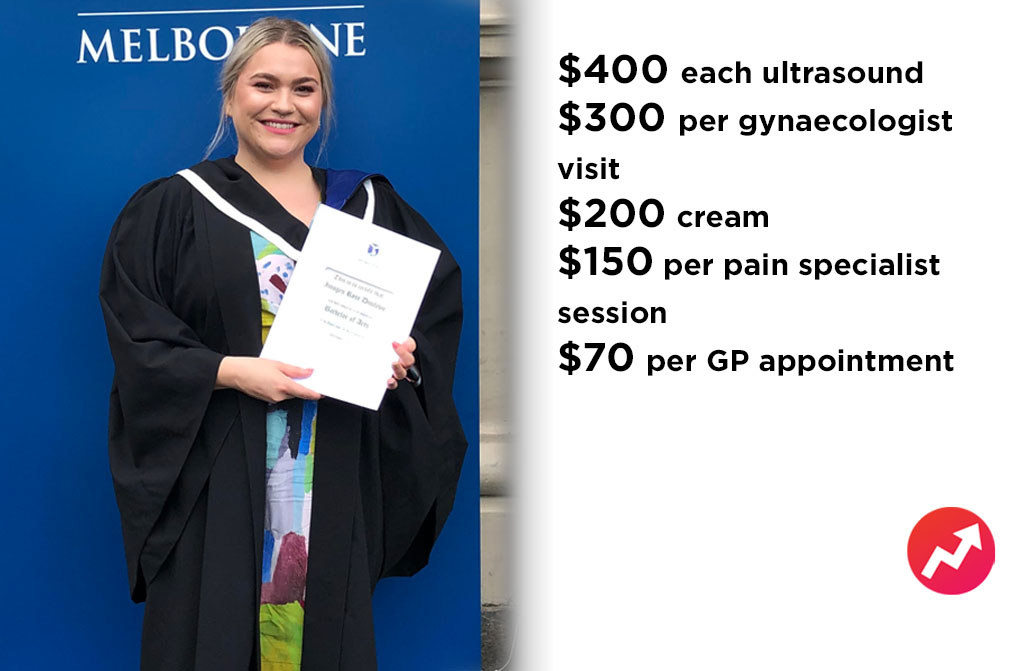

Endometriosis defined Imogen Dunlevie’s teenage years.

“My symptoms started with my first period, the day before my 13th birthday,” the 24-year-old told BuzzFeed News.

With each menstrual cycle she was in increasing pain until she was missing a week of school each month. She was told she was “unlucky” and that periods were sometimes painful.

“When I was 15 I got my period and had the most horrendous gastro-type symptoms, I was vomiting and screaming in pain and my mum took me back to the doctor, who finally sent me to a gyno who diagnosed me with endometriosis,” she said.

Dunlevie, who is now studying a masters of social policy, had her first laparoscopy and the doctors removed “as much as they could” of her endometriosis.

“My gyno said she had never seen so much endo in someone my age.”

Her symptoms continued and after an internal ultrasound she had another laparoscopy and scraping. At 16, she was also diagnosed with a uterine septum (where the uterine cavity is partitioned) and her doctor placed two intrauterine devices (IUDs) on either side of her uterus.

“I then had two more surgeries because nothing was getting better, and then one of my [IUDs] came out, which was a whole thing,” she said. “That took ages to get sorted because I kept going to emergency departments and they kept telling me I probably had chlamydia.”

At 22, Dunlevie had the septum in her uterus surgically removed and the IUDs taken out. Instead, a hormonal contraceptive implant was placed in her arm and she was prescribed Nafarelin, a hormonal medication used in the treatment of endometriosis

“It stops my period and removes the worst of my symptoms,” she said.

Patients can buy Nafarelin at a discounted rate on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme for five months before they pay full price.

Dunlevie said she wouldn’t have been able to manage her condition without her parents’ private health insurance.

“If I hadn’t had these surgeries, I don’t think I could have finished high school,” she said.

“I am incredibly lucky to have parents to cover this sort of stuff for me.”

There are out of pocket costs even with private health insurance including medication, anesthetist and other specialists.

“I see my gyno once or twice a year and that is always $300 a year and none of that is covered by private health; I see a pain specialist a few times a year and that is $150 each time,” she said. “He is an anesthetist who works in pain management because chronic pain has destroyed my nerves a bit so I’m always in pain even when I don’t have my period.”

Dunlevie also saw a pain psychologist.

“I now see a psychiatrist weekly, and I don’t think I would see one as often as I do if it wasn’t for all the issues related to my pain,” she said. “I had to see a pelvic physio for ages, so we ended up putting extras on our insurance for that.”

She also has to see a podiatrist because the pain has created issues with her leg muscles.

“I then have a regular GP who I see who is $70 an appointment but she bulk bills me occasionally.”

Dunlevie’s internal ultrasounds are $400 each and her bone scans are out of pocket, which aren’t covered by Medicare for younger patients without arthritis. A cream for pelvic pain is about $200, with no rebate.

She is currently casually employed while studying so getting sick is “very expensive”.

“I know I’ve gone to work when I definitely don’t feel well enough to be there, because the cost is too much to miss out on.”

Nurse Emily Zelesski has always had painful periods.

“Everyone told me it was part of being a woman and I needed to get used to it and take painkillers,” the 26-year-old told BuzzFeed News.

When Zelesski was 19 she was sent for an ultrasound, told she had polycystic ovaries and put on the oral contraceptive pill, which she eventually came off for cardiac issues.

“When I came off it I had the worst period pain I’ve ever had in my life and it got to the point where I was getting pain every single day, outside of my period cycle,” she said. “When I was 24, I finally got someone to listen to me that something wasn’t right.”

Zelesski had a laparoscopy and surgeons scraped out her endometriosis.

“I wasn’t out of pocket for that and I have basic health fund cover,” she said.

After two months of relief the symptoms came back “full throttle”.

Just seven months later she had another laparoscopy in which more tissue was removed along with a cyst on her ovary. Doctors also diagnosed her with adenomyosis, a condition in which the inner lining of the uterus (the endometrium) breaks through the muscle wall of the uterus.

“[My surgeon] said we found one of the endometriosis biopsy results was on the wall of the uterus where the bowel sits and if it had grown anymore we would have done bowel surgery,” Zelesski said.

Not all endometriosis patients can afford the specialists they’re referred to. Zelesski and her partner had a combined income of $40,000 in 2016 when she was referred to a pelvic physiotherapist.

“Even with the chronic pain management scheme they have, it was $100 a session so I couldn’t afford it,” she said.

Zelesski was referred to a gastroenterologist and urologist.

“The urologist was $280 and it was 10 minutes and they told me to take the same medications you would give an elderly person with an overactive bladder, and then I haven’t seen the gastroenterologist because it is ridiculous paying that much money for something that may or may not help,” she said.

She is having acupuncture every one or two weeks for $100 per session and recently had a $150 iron infusion.

“Because I bleed so much, I’m constantly in an anaemic state so the infusion has been great,” she said.

Zelesski said she has been “caught out” a few times by referrals to get ultrasounds at places that don’t bulk bill.

“They can cost $200 and that is a lot, especially when I was a student.”