In the United States of America, there are currently 2.2 million people who are incarcerated, making the US the world leader with 670 individuals imprisoned for every 100,000. At such staggering numbers, it may be difficult to comprehend that behind each of point of data, there is a person with a life and story.

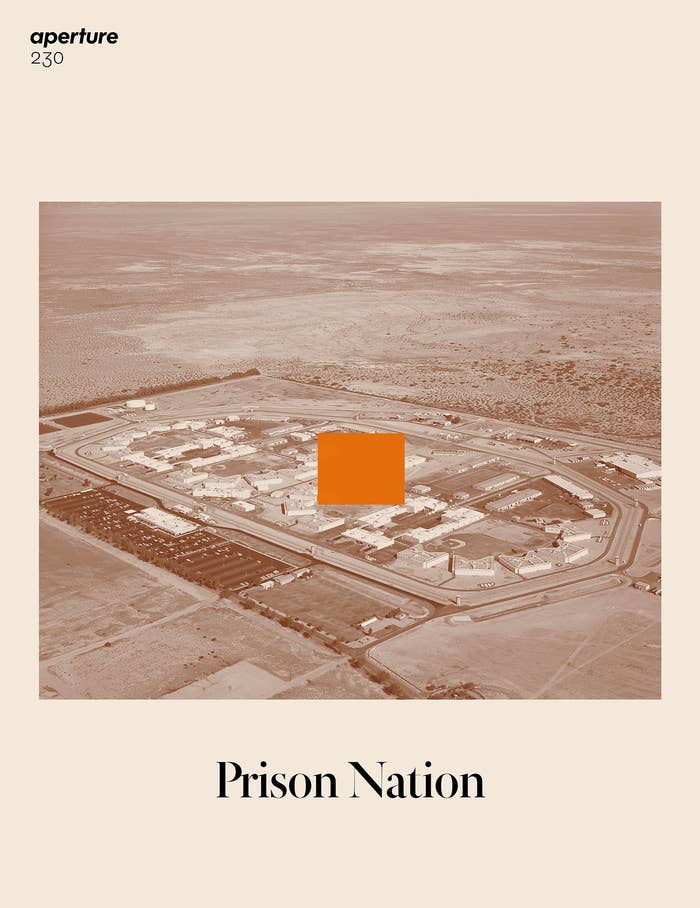

The latest issue of Aperture Magazine, Prison Nation, approaches the topic with a single question — is it possible for pictures to tell the story of mass incarceration in the US when the subjects themselves have forfeited control of how they are represented?

Here, BuzzFeed News hears from Michael Famighetti, the editor of Aperture Magazine, on the difficult relationship between photography and incarceration:

The issue asks how the public can see — and better understand — the human cost of mass incarceration. The issue delves into the myriad ways that photographers have addressed the crisis of mass incarceration in the United States, which has an alarmingly large prison population. Often we see clichéd representations — an over-reliance on features like barbed wire, steel bars, etc. — of prison life.

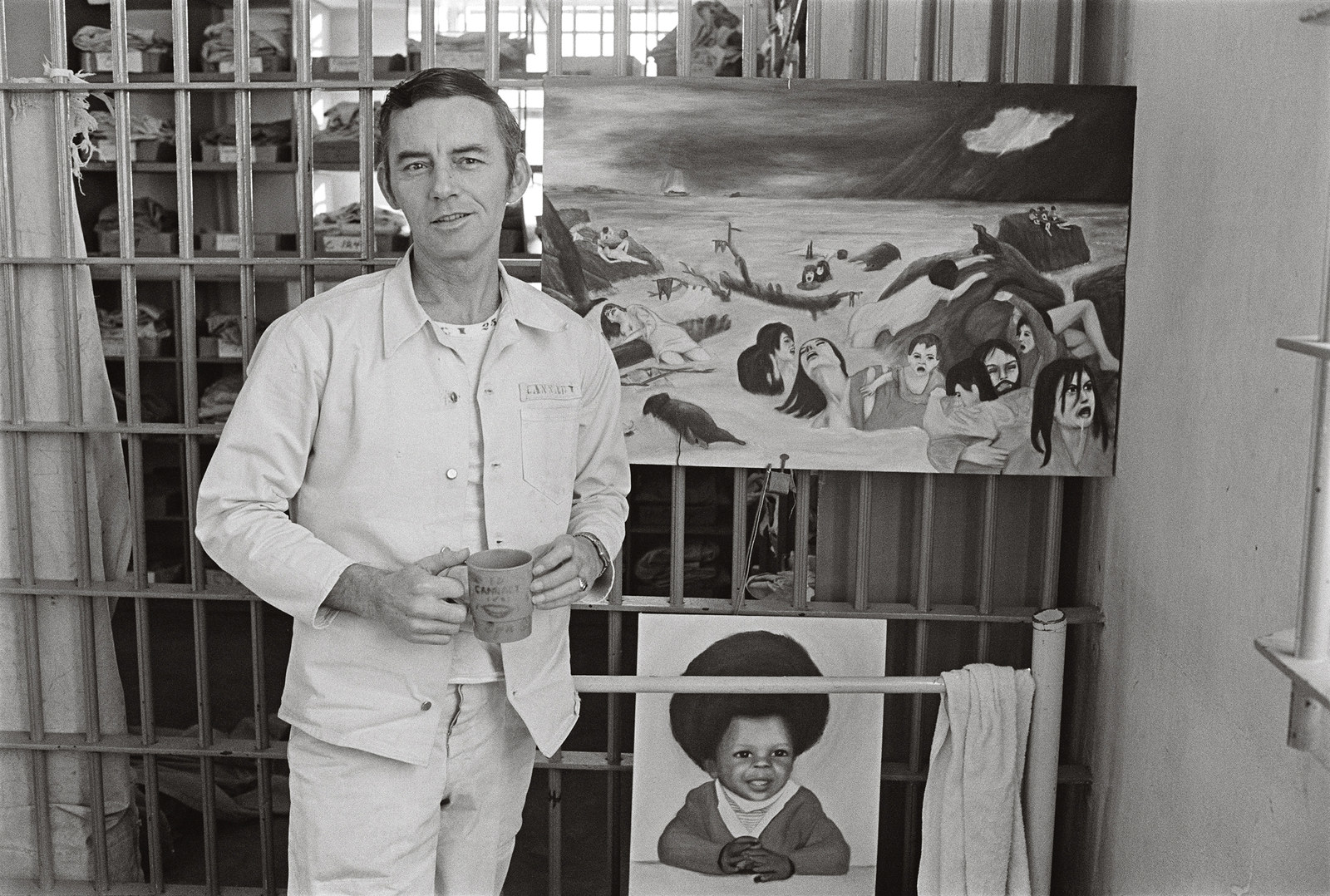

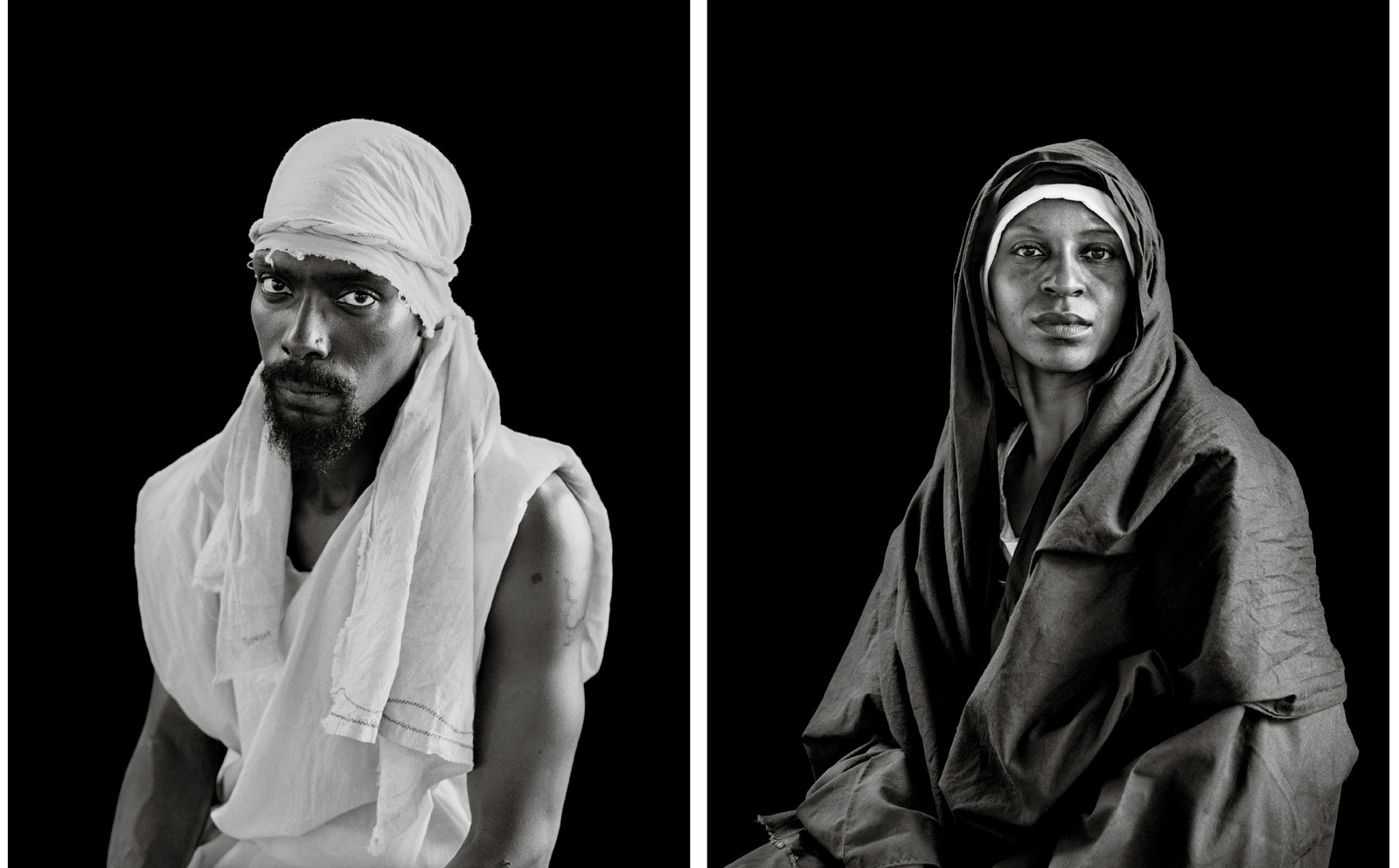

Our aim was to complicate that image vocabulary by presenting a range of projects that highlighted the individuality and humanity of people caught in this carceral system.

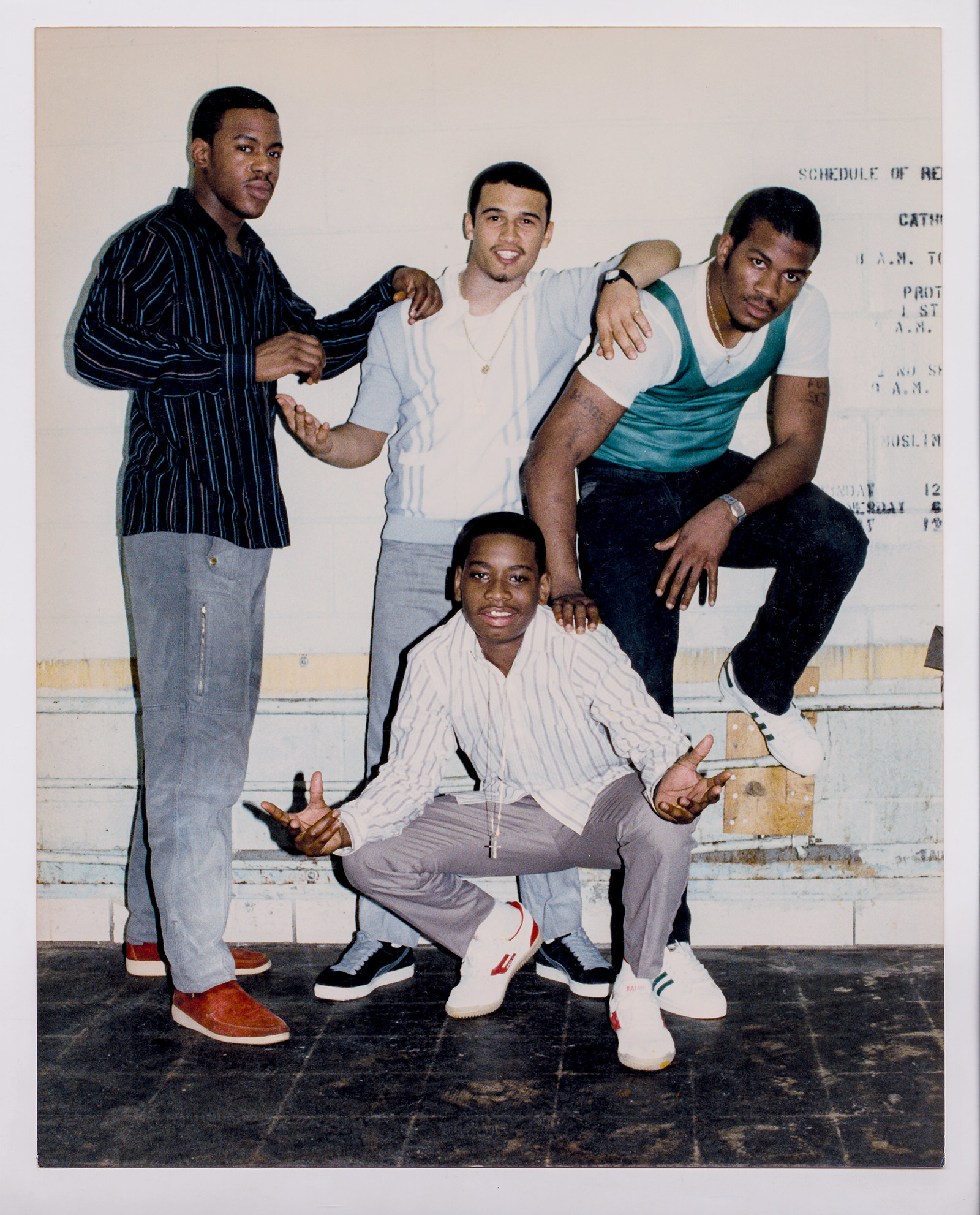

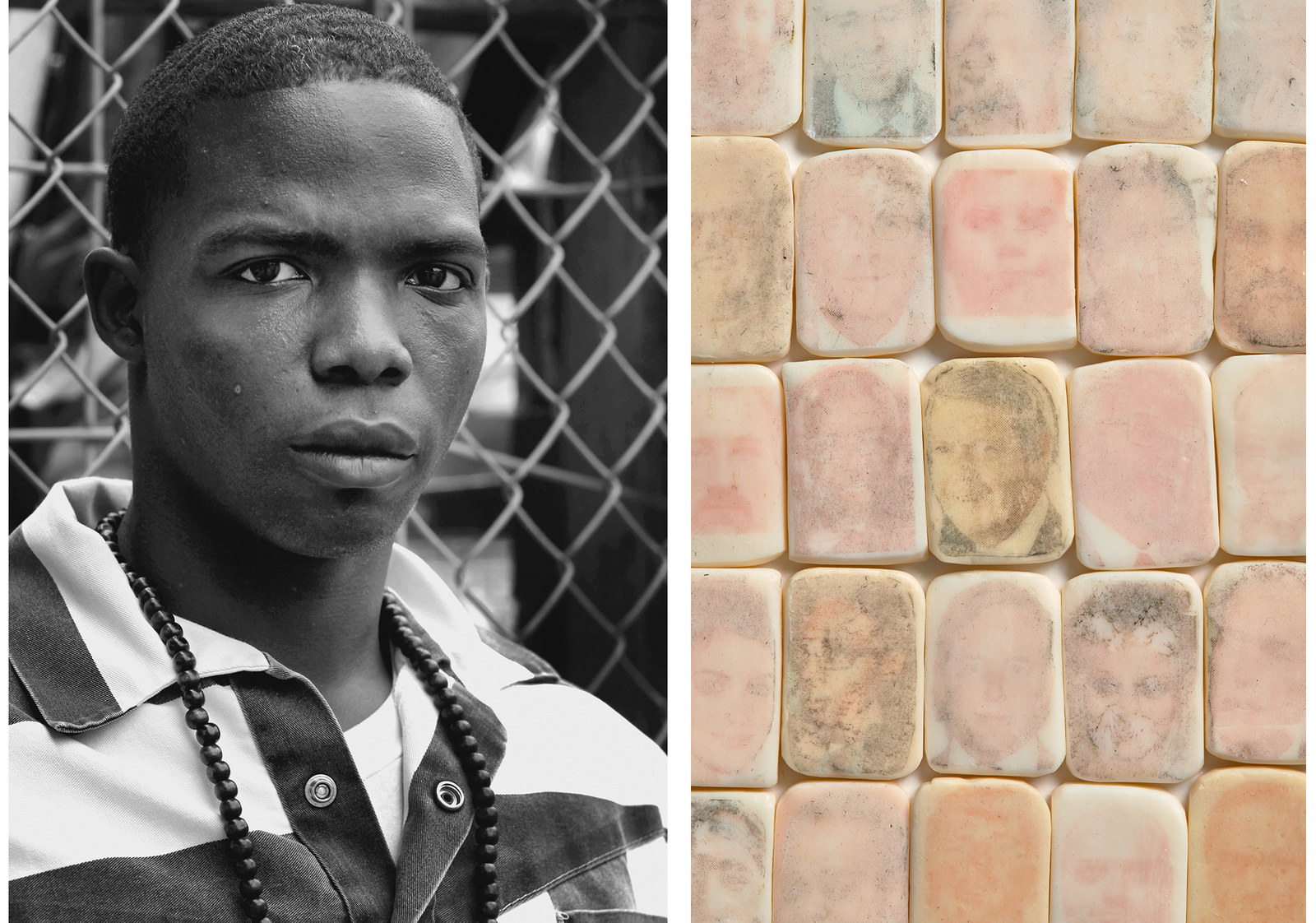

To do that, it's important to include the voices and perspectives of those formerly incarcerated. Jesse Krimes made his photo-based installation work while he was incarcerated by ingeniously repurposing prison-issue materials, like prison soap, while artists such as Joseph Rodriguez was incarcerated as a young man and then turned to documentary photography and has since focused his work on the criminal justice system.

When you look at the sobering statistics — more than 2.2 million people are incarcerated in the United States and the rate of incarceration is disproportionally high for people of color — it is self-evident that this is one the urgent social issues of the day. But this is a huge issue that often remains out of view for those whose lives have not been directly touched by incarceration.

That said, everyone is touched by this system; we are all complicit, as incarceration has become a form of governance.

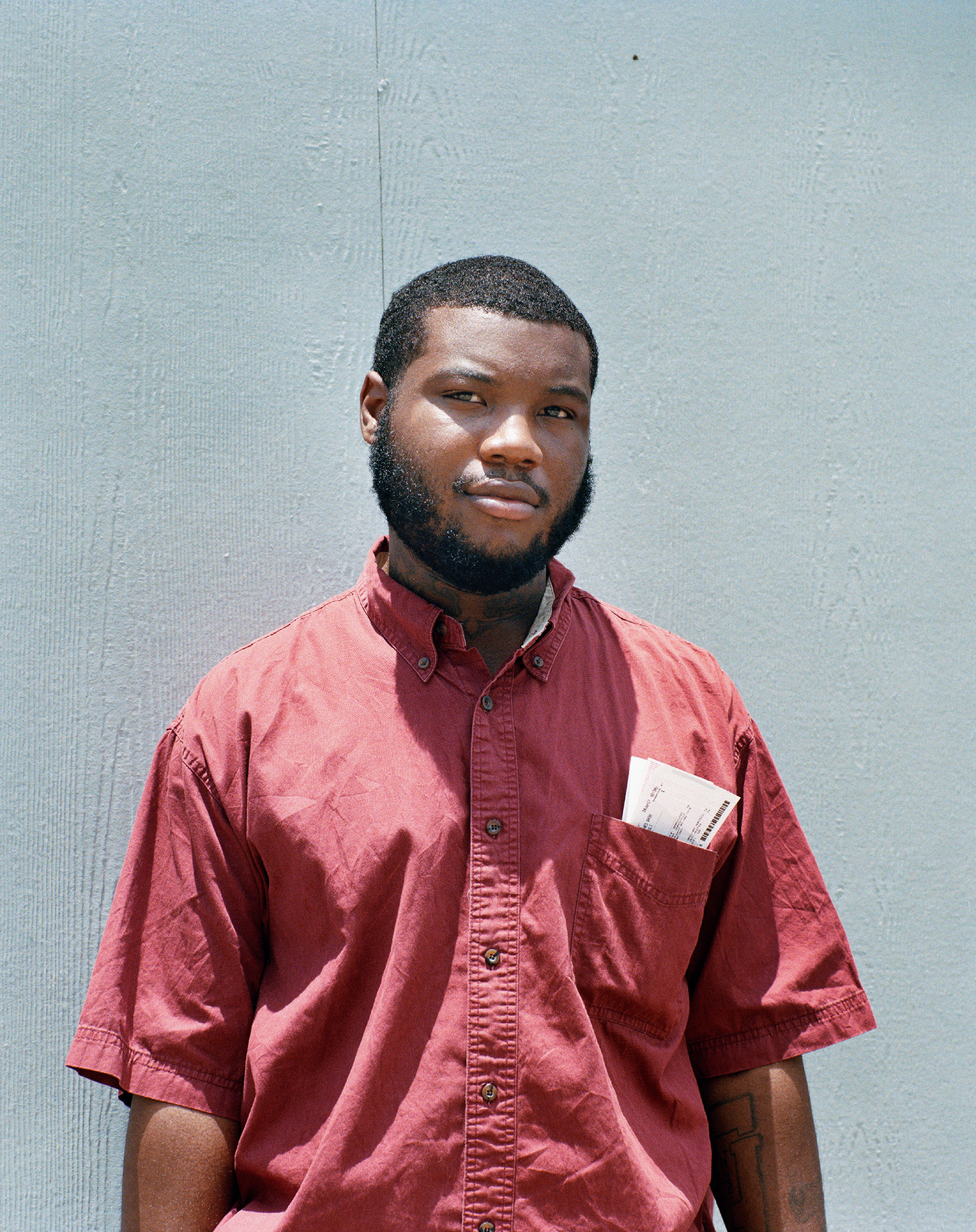

The are many interconnected themes in the issue — from the history of photography in relation to framing groups of people as criminal types, to the experiences of incarcerated women, to the experience of correction officers, to the perspectives of recently released men and women who are reentering society. That said, an emphasis on individual lives and stories is the binding agent.

In contrast, though, a project like Stephen Tourlentes' almost sublime prison nightscapes gives us the big picture: Here we see how prisons are an omnipresent feature of the American landscape, often serving as the economic engines of rural communities.

A photographer’s work can be a starting point for a conversation about what this crisis looks like and complicate our ideas of what we imagine the experience of incarceration to be. The issue also puts today’s situation of mass incarceration in historical context. The visionary legal thinker Bryan Stevenson is interviewed in our pages and discusses the current crisis within the context of slavery, segregation, and institutional racism — he also considers the role of images and culture in shaping how we narrate these fraught histories that have shaped our contemporary condition.

At Aperture we are interested in how photography and art can engage society. Each issue of the magazine is themed, and a theme usually arises from us seeing strong bodies of work that are delving into a specific area or set of ideas. Despite the increasing difficulties of gaining access to photograph inside prisons, there is incredibly strong work being made by talented, dedicated, and persistent photographers. For the issue, we were looking for bodies of work that addressed different angles on the subject — Tourlentes' images, as mentioned, provide a wide-angle view, while Lucas Foglia, for example, focuses on one very specific story from Rikers Island, a garden therapy program.

We were looking for a range and balance of stories, across time, geographies, and formal strategies, and we hope that reader will walk away with a complex and nuanced understanding of America’s carceral state.