For many people, Star Wars is more than just an action-packed space opera or a franchise worth over $4 billion, the films also represent a very specific time and place of personal realization. When those iconic yellow letters first crawled across movie screens in 1977 to introduce Star Wars to the world, it was an invitation to a universe of oddity, excitement, and hope, which for many children set the tone for the rest of their lives.

One such kid was film historian Paul Duncan, whose dozens of books have celebrated and explored some of the most iconic films in history. His new book The Star Wars Archives: 1977–1983, published by Taschen, dives deep into the Lucasfilm archives to reveal the untold and obscure stories behind the movies.

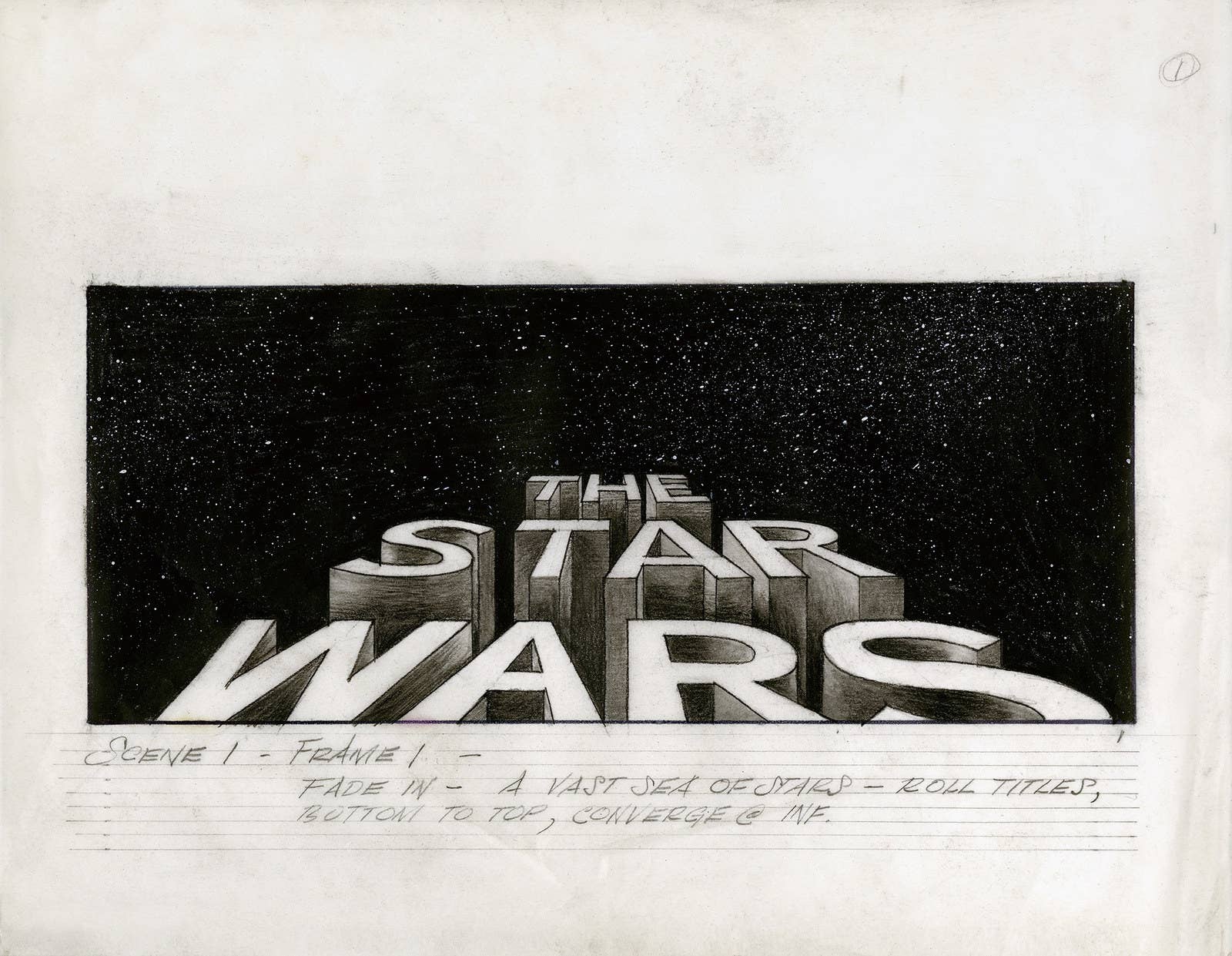

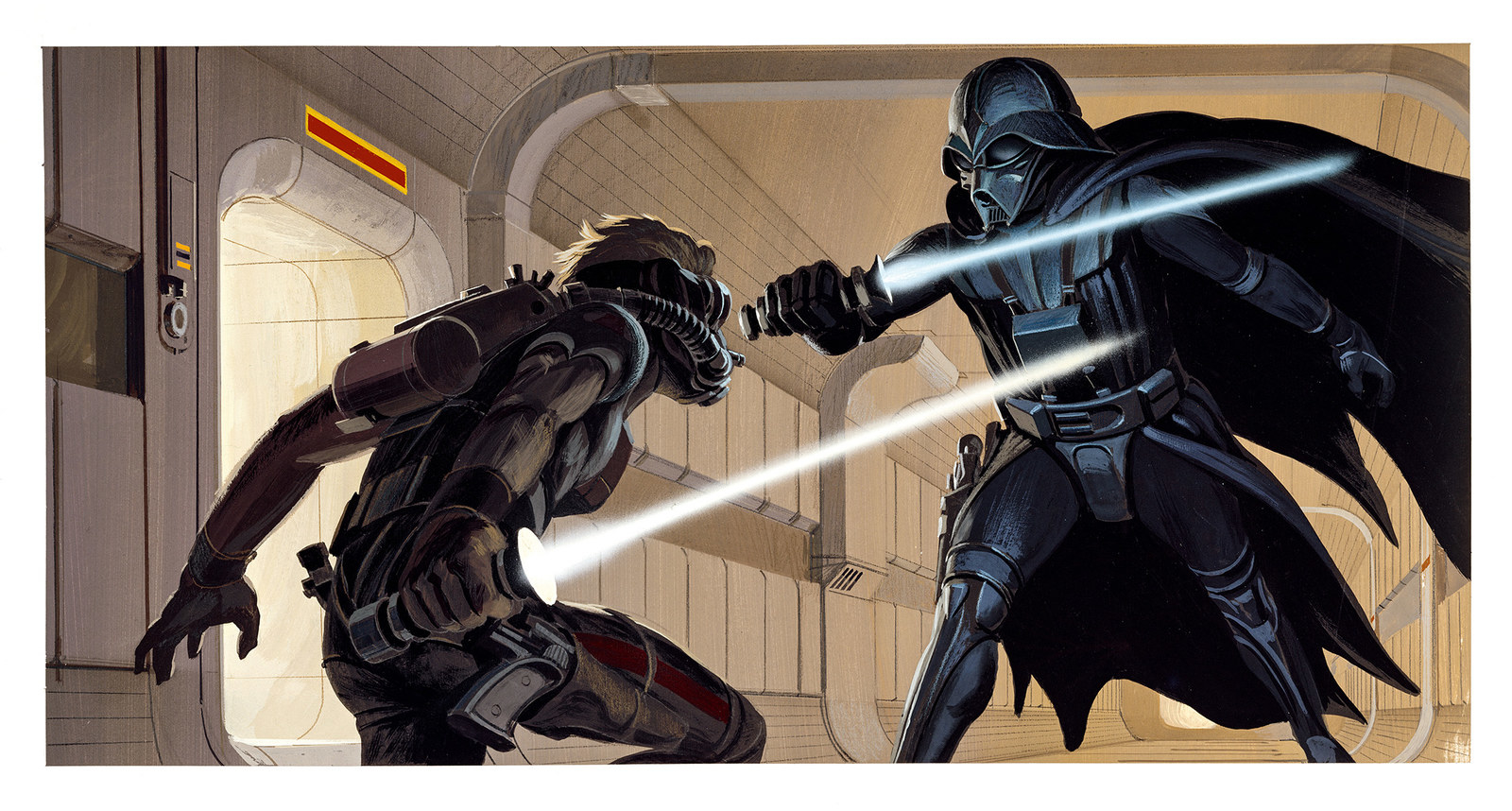

Each page of rare, behind-the-scenes pictures, illustrations, and storyboards are guided by George Lucas himself, who collaborated with Duncan to help tell the true stories behind images. Here, Duncan shares some of his favorite pictures and stories from the book, and reveals his own personal introduction to the incredible world of Star Wars.

In the early 1970s there was the Vietnam War, Watergate, the resignation of President Richard Nixon, and a general air of pessimism, doom, gloom, and paranoia. This was reflected in the culture as well. For example, George Lucas’s first film, THX 1138 (1971), is about a future authoritarian society that provides everything for its citizens except free will. However, after Lucas cowrote and directed American Graffiti (1973), a box office success that promoted an optimistic and more positive life experience, he decided to continue in that vein with Star Wars.

When Star Wars opened in 1977, its effect was to give joy to millions of people. It was very fast-paced, full of exotic locations and characters, and told in a direct, no-nonsense style that even the youngest viewers could follow.

After it broke box office records, the immediate response by the industry was to copy the science fiction tropes, to copy the direct storytelling, and to copy the visual effects — but without understanding the underlying philosophy of the series. One of the reasons for doing this book was to highlight this underlying philosophy and to get George to talk about it.

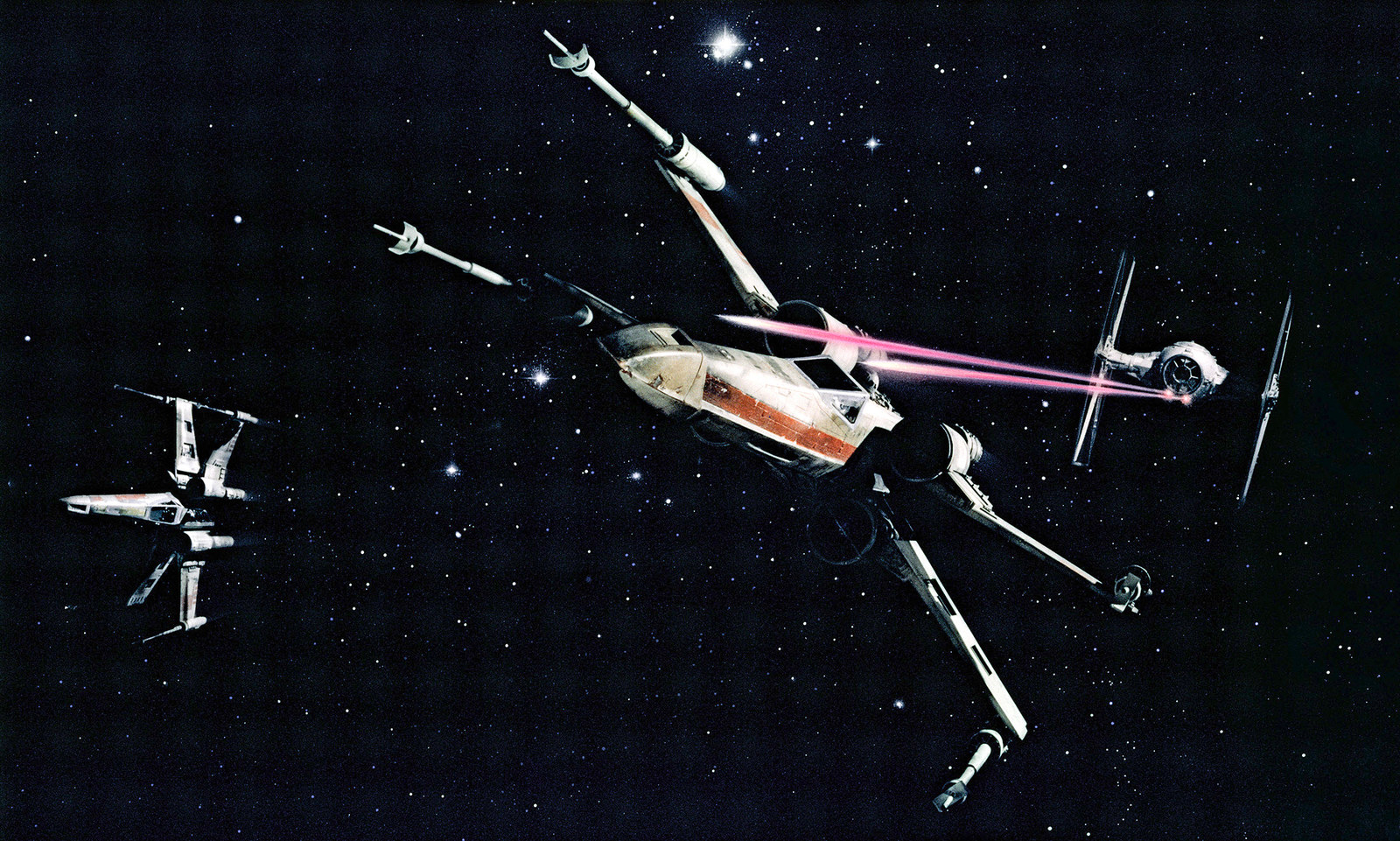

Technically, Star Wars gave a kinetic energy to cinema. Just as Garrett Brown’s Steadicam freed the camera to go anywhere, as seen in Rocky (1976) and The Shining (1980), the team at Industrial Light & Magic freed the visual effects camera to move anywhere the director wanted. And from a business point of view, Star Wars and Rocky showed the industry that you could build a brand and a franchise over several movies, which paved the way for trilogies and franchises as diverse as Alien, Back to the Future, and Lord of the Rings.

Artistically, Star Wars presented a moral fairy tale with the simple message that love and compassion and kindness, combined with a lot of training, hard work, and discipline, can defeat an empire. The films have created a worldwide fanbase inspired to both work in creative industries and do a tremendous amount of charity work.

About a year into the research for this book, I realized that what I was really interested in was George Lucas, his creative process, and his thoughts on directing and producing the movies. Once I had made that decision, the book quickly came into focus and became an oral history told as much as possible from the point of view by George Lucas. George was kind enough to give me three days of interviews to answer all the questions I had, which was an amazing experience.

One thing I was surprised by was George's really good sense of humor. It's dry, just like mine. I wanted to make sure that this was present in the book, for readers to get a feeling of what he is like in person, so I included some of our playful exchanges in the text.

Normally when I am doing research, there is one archive in one location. On this book there were five archives in four locations — one location was Lucasfilm at the Presidio in San Francisco, and the other three locations were on Skywalker Ranch in Marin County, California.

I looked at every photograph, at all the concept art and storyboards by Ralph McQuarrie, Joe Johnston, and Nilo Rodis-Jamero, at all the scripts, at all the Industrial Light & Magic and Lucasfilm production documents, and at all the press clippings. I spent eight months just researching — eight hours a day making annotations and copies, and then evenings and weekends processing the materials.

The next stage was to organize it all. A chronology of events was put onto spreadsheets, using the production documents as a primary source. All the clippings and production interviews were digitized, the quotes extracted and put into spreadsheets. Giant text files were then generated combining the two so that I had hundreds of pages of quotes in chronological and subject order.

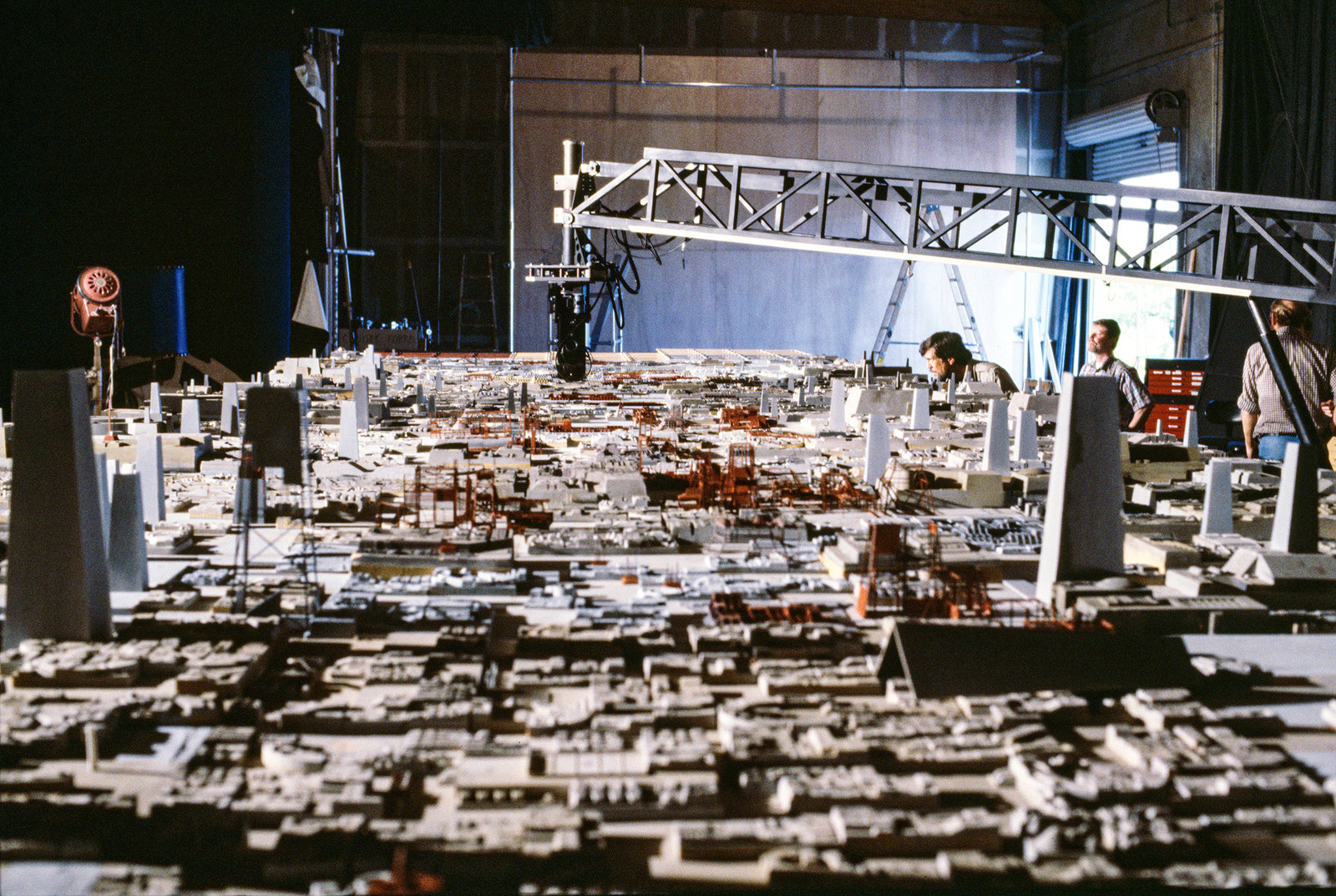

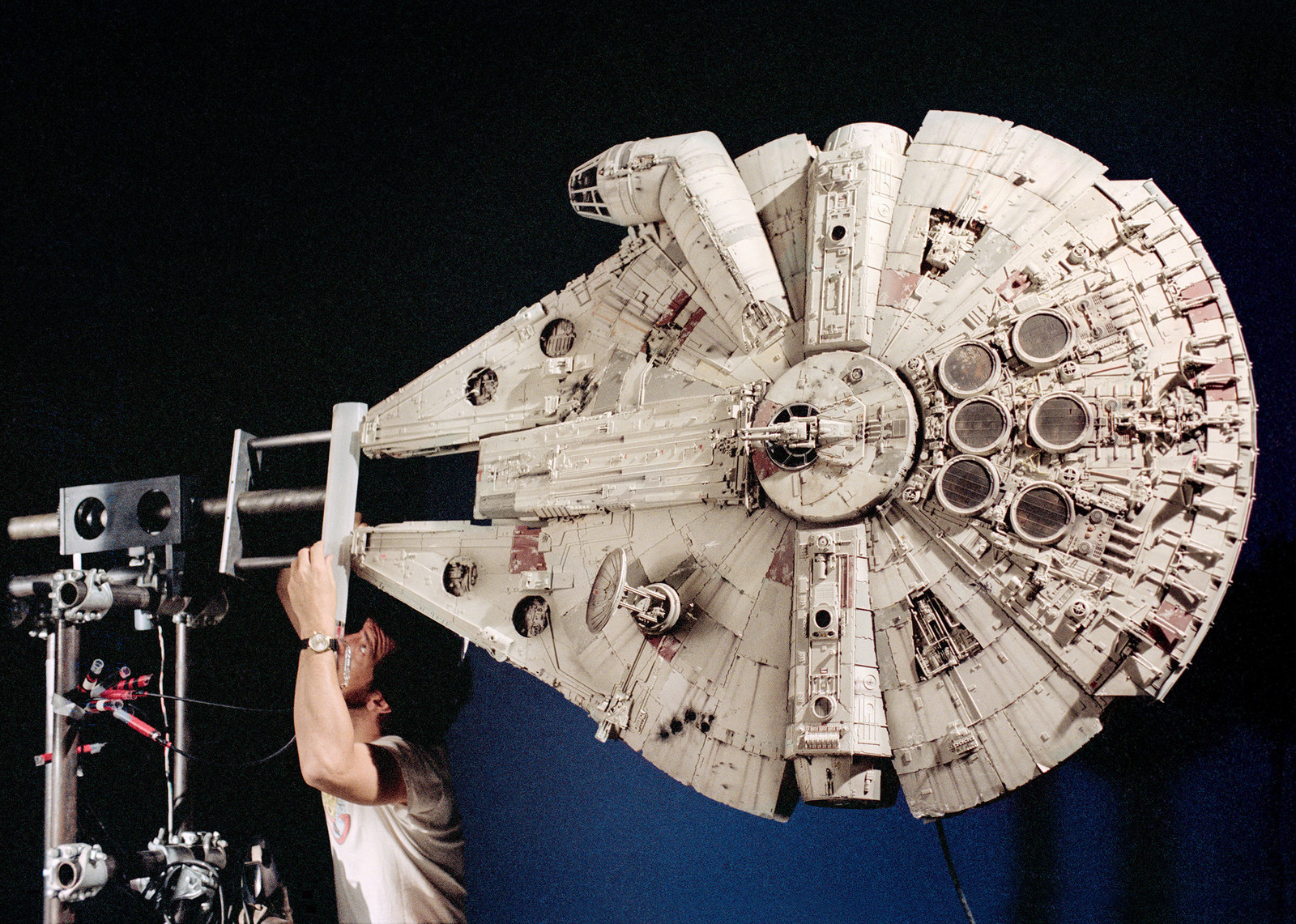

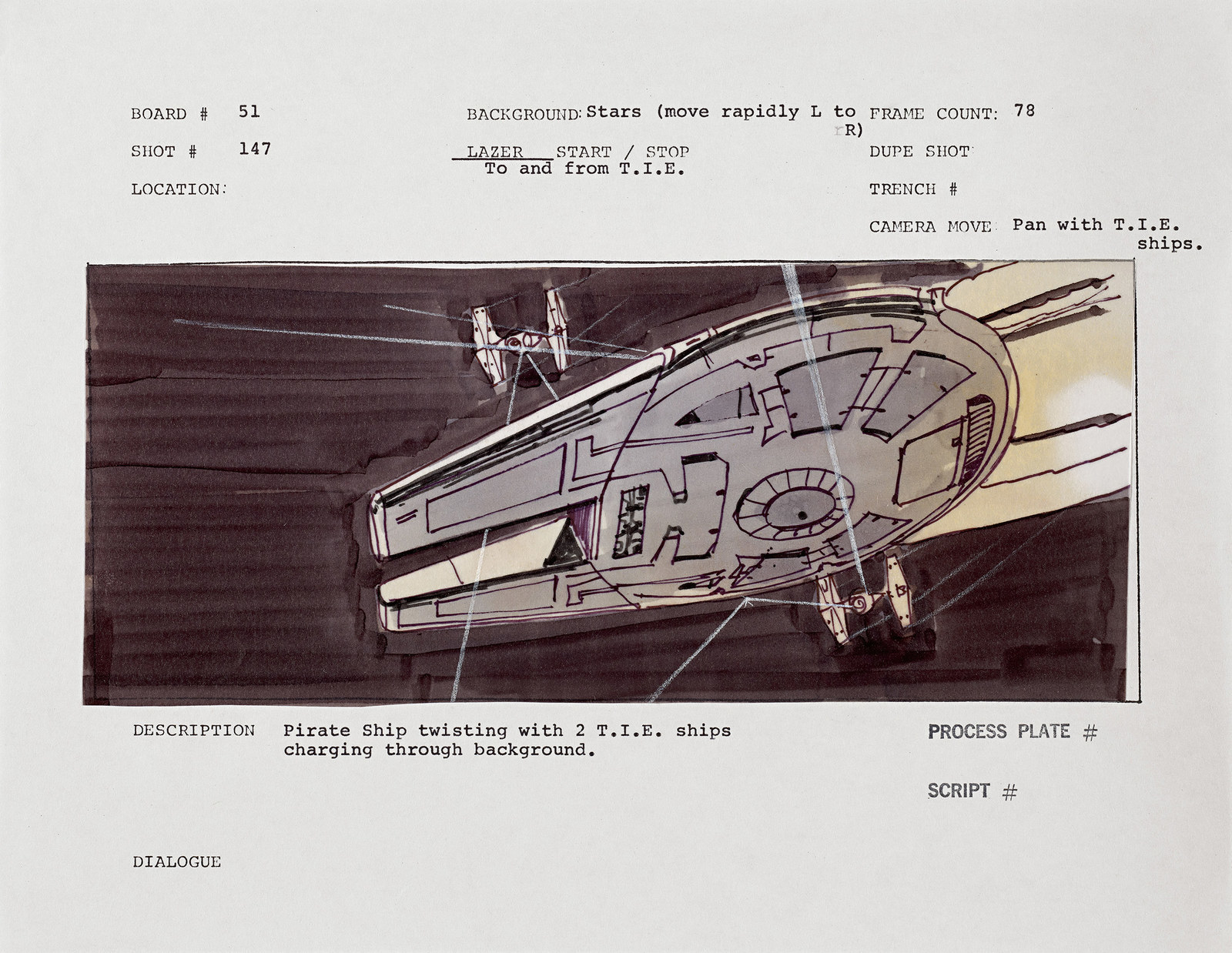

I decided the best way to present the images in the book was in film plot order. This way I could show the processes and decisions that went into each and every scene. For example, there is a spread of Joe Johnston’s original designs for the Millennium Falcon, then a spread showing how the model was made by Industrial Light & Magic in Los Angeles, and then a spread showing how the full-size exterior was constructed on set in the UK. The model and set were being made at the same time, so they were constantly sending reference materials back and forth so that their Falcons matched.

I also included images from deleted scenes, as well as storyboards and concept art for scenes that were never made, like the Emperor’s lava lair for Return of the Jedi. There are also reproductions of production documents, story conference transcripts, and script pages that have never been seen before.

The biggest challenge was how to fit it all into such a small book — it’s only 600 pages!

There were so many surprises in both the stories and the imagery that it is difficult to point out just one thing. I was astounded to find out that during postproduction on Star Wars, George had the idea of putting a stop-motion animation figure of Jabba the Hutt over the actor, but he didn’t have the time or the budget, so he cut the Jabba scene and reshot the scene with Greedo with additional dialogue.

Also, there was the realization that Ewoks are integral to Return of the Jedi. Consider this: It’s very easy to fight against something and to say that it’s bad, but in any confrontation you also have to know what you are fighting for. When Luke, Leia, and Han are with the Ewoks, this is the only time that we see a community in these movies, with all the different generations living and working together, telling stories, having fun, helping, and supporting one another.

When the Ewoks agree to help the Rebels, they do so to preserve their community. They know what they are fighting for, even though the odds against them are overwhelming — they are small, not physically strong, and only have wooden weapons to wield against the technological might of the Empire. So the Ewoks represent what the Rebels are fighting for.

During the story conferences, it was interesting to see how George took input from everybody and was happy to change plot details as long as it enhanced the characters and emphasized the philosophy behind the series. Conversely, he was completely intractable if the ideas hurt the philosophy he had built up.

There were many amusing notes in the production documents — one take on Return of the Jedi was that it was no good because “Han killed too many of his own men.”

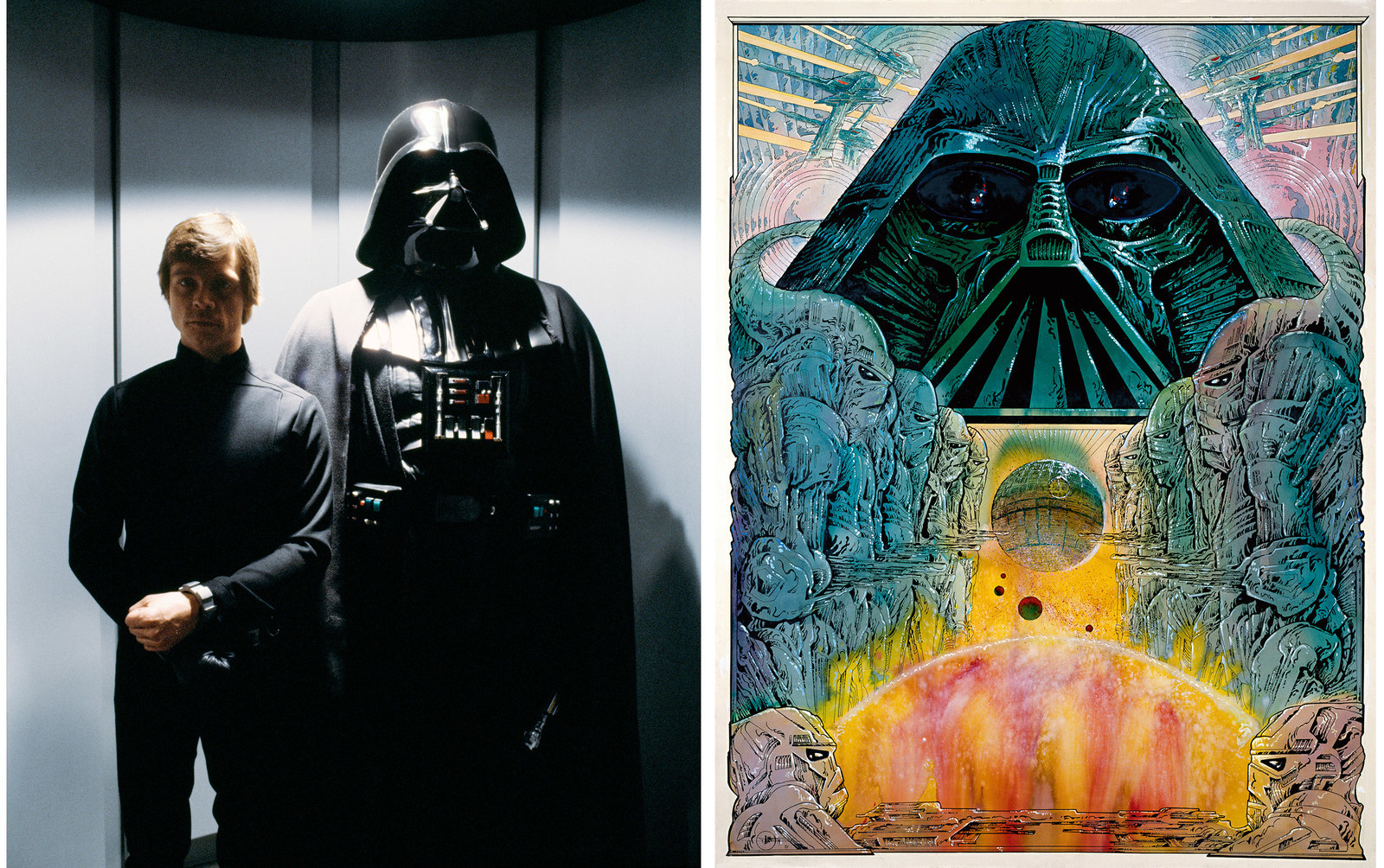

It was clear that the actors and the Industrial Light & Magic technicians were having a blast — there are many images of them clowning around. In contrast, George was often reflective on the set and very precise in his positioning of the characters and their gestures.

It wasn’t until I finished the book that I realized how much Star Wars had actually influenced my career. In 1977, late May, I had just turned 13, on school holiday, at home, sitting on the carpet, eating baked beans on toast, watching the BBC news at midday. At the end of the broadcast was a report on the hullabaloo surrounding a new movie sweeping America. I saw long queues in front of the cinemas and clips from the movie.

I sat there transfixed, sitting on the carpet, cold baked beans on soggy toast, as geometrical black ships swooped and tumbled as they fired laser beams at a sleek flying saucer. I was hooked.

From that moment on, through the summer and fall of 1977, I searched for and collected every scrap of information I could about Star Wars, and the first day it was at my local cinema — Sunday, Jan. 29, 1978 — I begged my father to drop me off four hours before the first showing so that I could have a chance of getting a seat, because surely this was going to be the biggest thing to hit Nuneaton, England, since Ben-Hur, or even Gone With the Wind.

I walked around the back of the tall redbrick building to the backdoor, and there was not another soul to be seen on that cold, wet winter’s day. So I waited, and waited, and waited some more, playing with the money in my pocket, waiting to see the first movie I would see by myself.

Eventually, I paid for my ticket. I sat. It went black. The opening line — “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” — then…BANG, title, music, spaceships. The cold and wet melted away, and I was exactly where I wanted to be.

Although I did not know it then (how could I?), Star Wars opened my mind to future possibilities and started me on a direct path to the here and now of my life — writing and editing books on cinema. Two years later, I started my own fan magazine, and the first thing I wrote was a piece on The Empire Strikes Back. For this reason, I dedicated the book to my 13-year-old self — and all our 13-year-old selves.

Making a movie like Star Wars is tough, hard work, with long hours and unrelenting deadlines, but the intelligent, talented people making these films were operating at the top of their game and delivered in spades. They were led by George Lucas, who encouraged excellence in all aspects of the filmmaking process by giving people the courage to try new concepts, fail, and then try again until the work met his exacting standards. This combination of business savvy, technical innovation, and artistic endeavor is shown and explained in the text, images, and documents in the book.

If just one person is inspired to tell stories or make movies as a result of reading this book, I will have considered my time well spent.