Since its establishment in 2003, the National Museum of African American History and Culture has helped to preserve and recount the African American experience through its collection of more than 36,000 historical artifacts. In 2016, the museum opened the doors to its new Washington, DC, location, comprised of approximately 85,000 square feet across five floors of exhibition space.

At the center of these collections are Michèle Gates Moresi, who oversees the museum's acquisitions and conservation efforts, and Laura Coyle, head of the museum's digitalization programs. Together, Coyle and Moresi have co-edited a new book, titled Pictures With Purpose: Early Photographs From the National Museum of African American History and Culture, that dives deep into the museum's archives to uncover many of the earliest pictures to document the African American experience.

Here, BuzzFeed News speaks with Coyle and Moresi about their new book as they discuss the editing process and the cultural context in which these powerful pictures were made.

Can you speak about the range of photographers featured in this book? Who were they, and in what capacity were they documenting the lives of black Americans?

Laura Coyle: This book includes a broad range of photographers: black and white, male and female, amateur and professional, established in studios and itinerant. Photography arrived in the United States in 1839, the same year it was invented, and within a year, the first studios opened in America. As the technology quickly improved, the demand for portrait photographs increased rapidly.

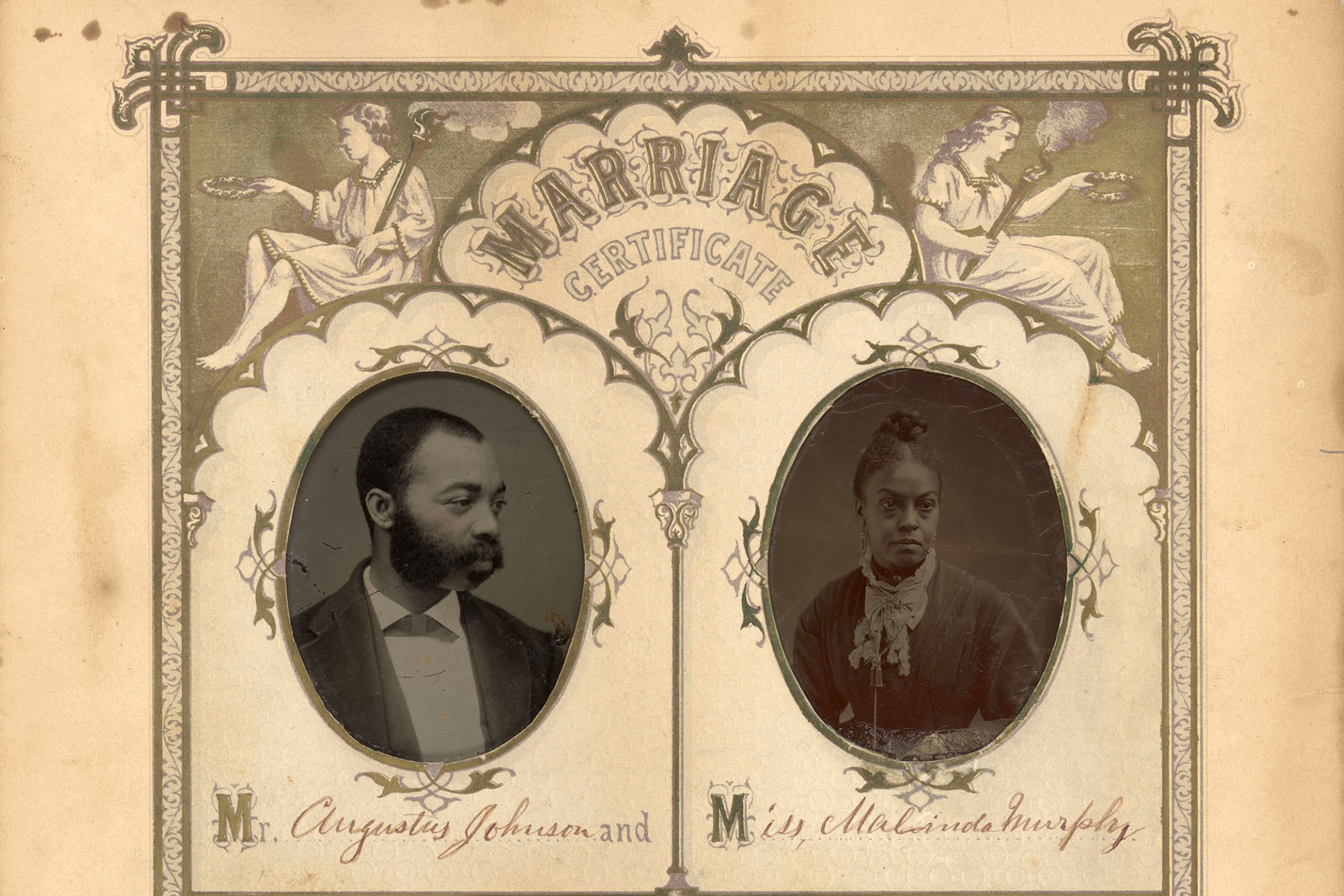

African Americans opened some of the first photography businesses in the country. As becoming a photographer became simpler and less expensive during the course of the 19th century, hundreds more African Americans became professional photographers, running their own studios, traveling with their cameras, or working for other photographers.

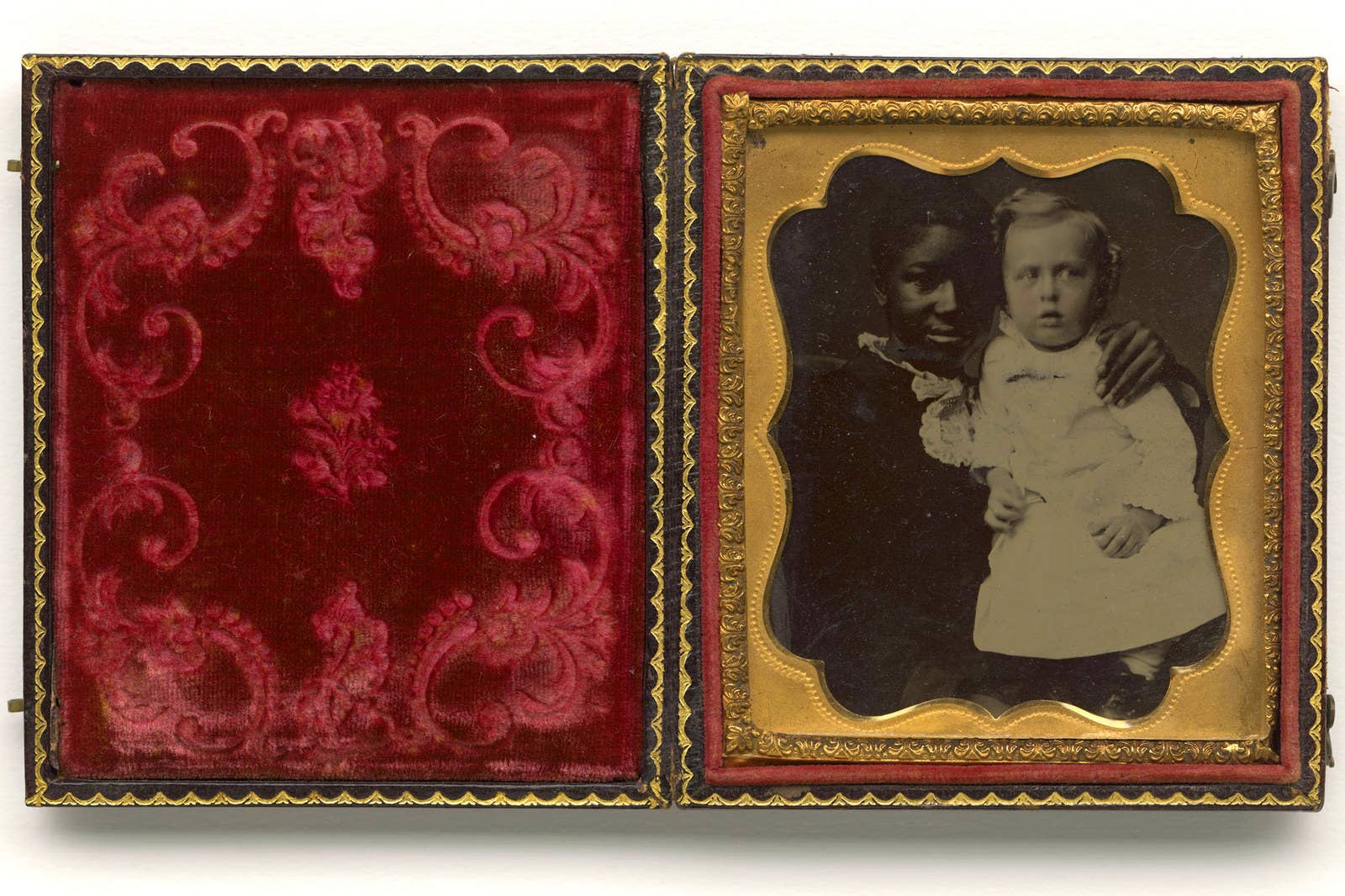

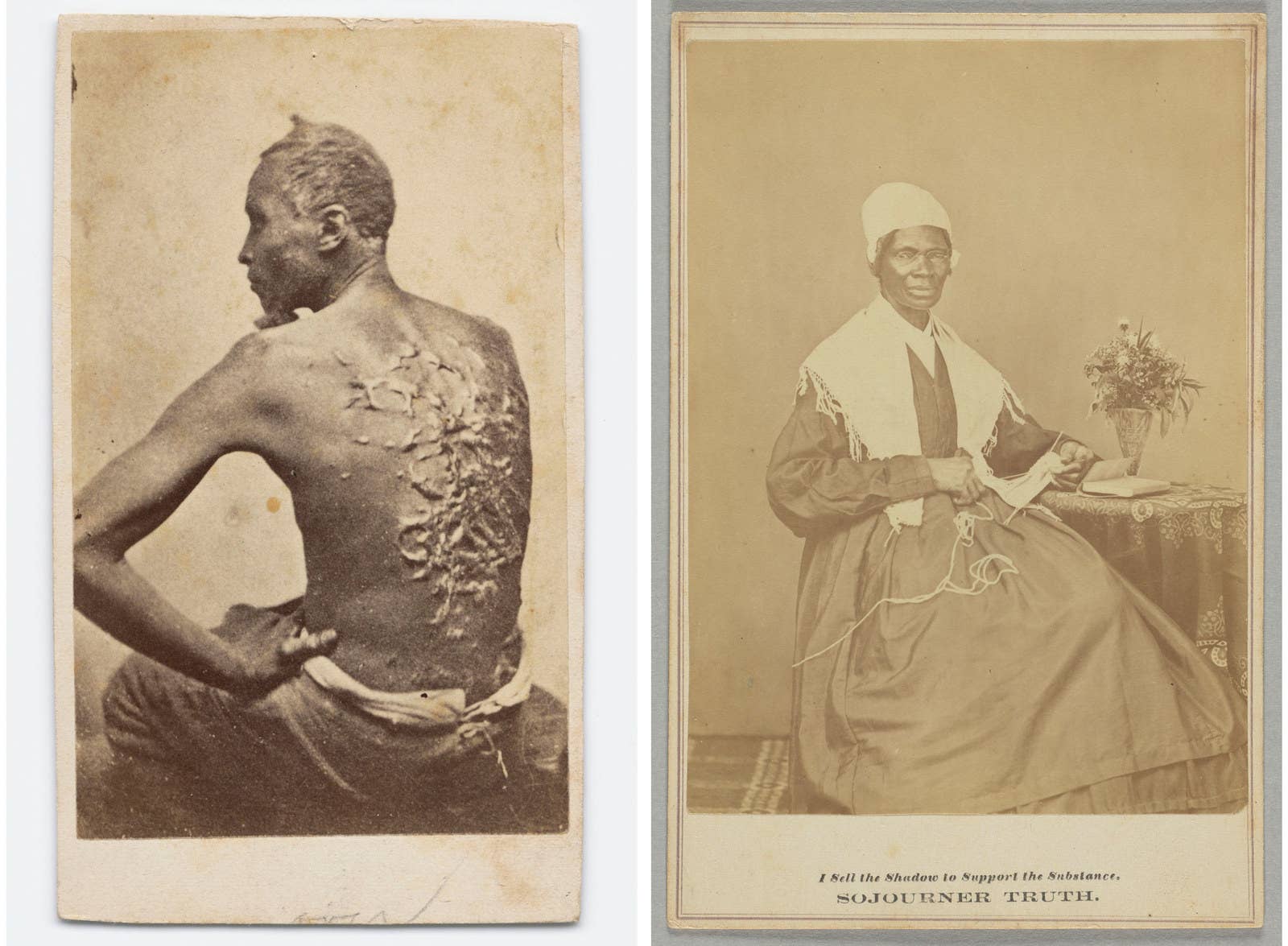

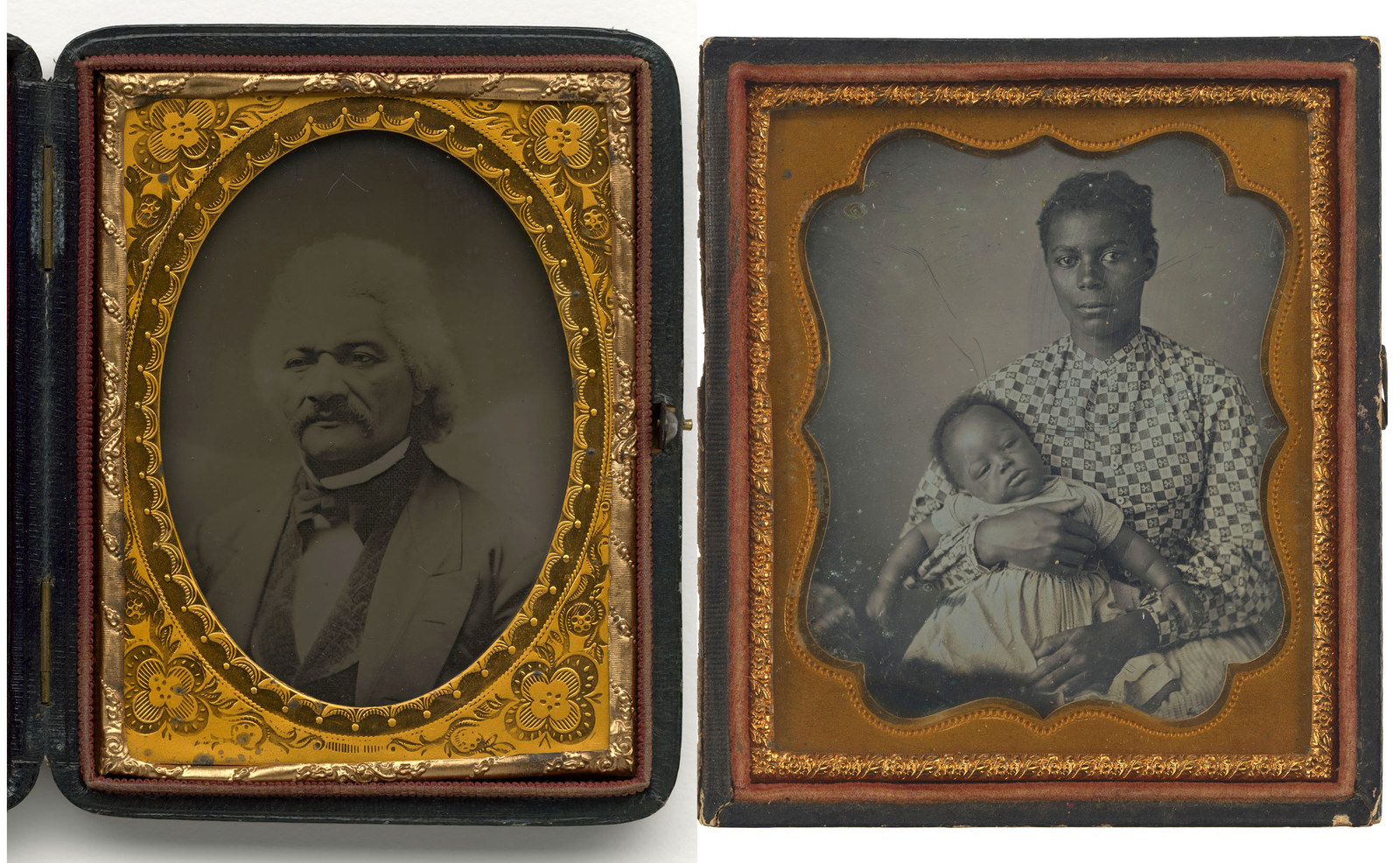

Our book shows that black and white photographers were capable of making sympathetic photographs of African Americans. However, African American photographers and sitters shared a special bond and a personal stake in portraying black subjects respectfully. They realized that with the images they created and commissioned, they were not only affirming the worth of particular people but also of the entire race within a larger society that often denigrated them.

Can you speak a bit on the eras represented in this book?

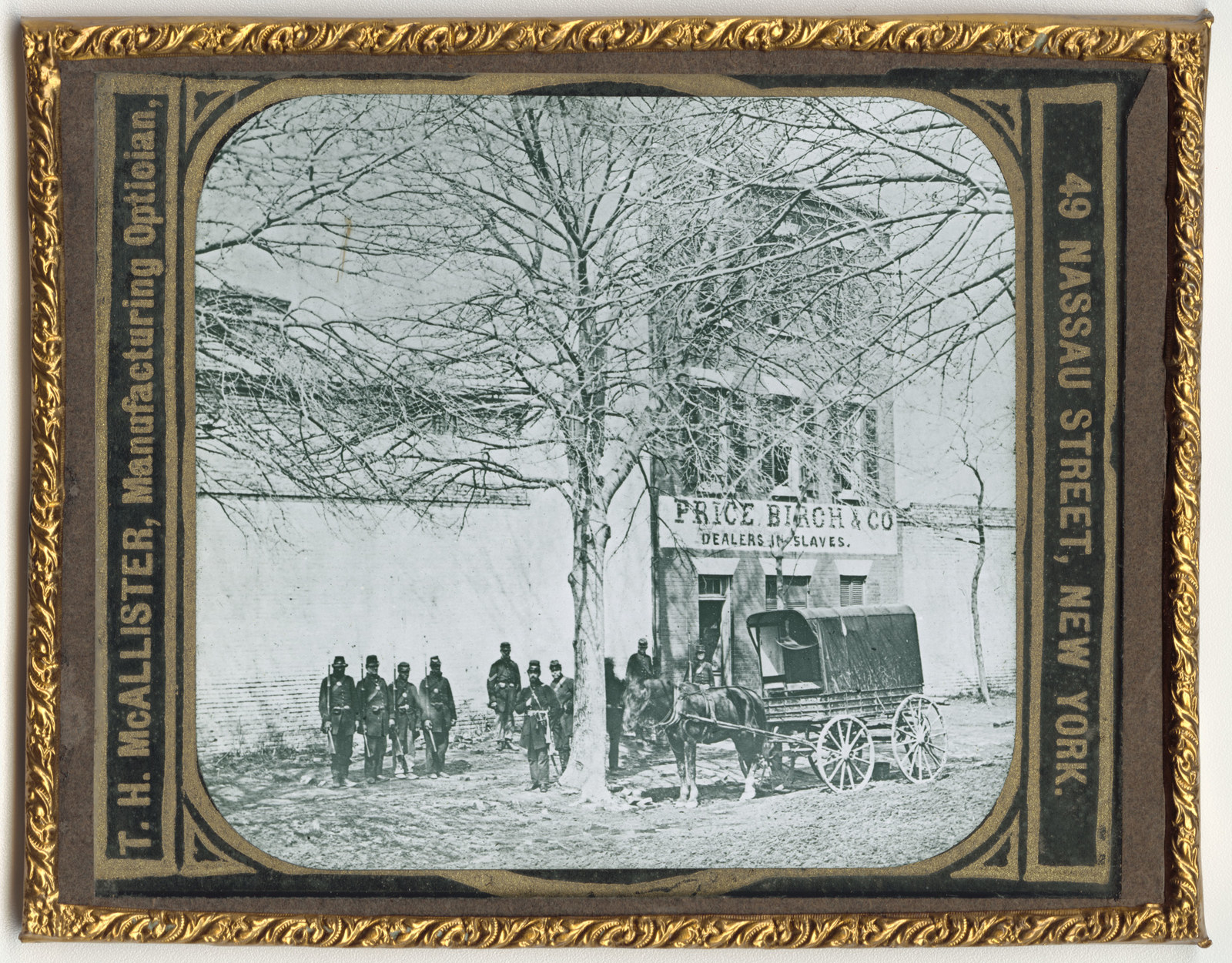

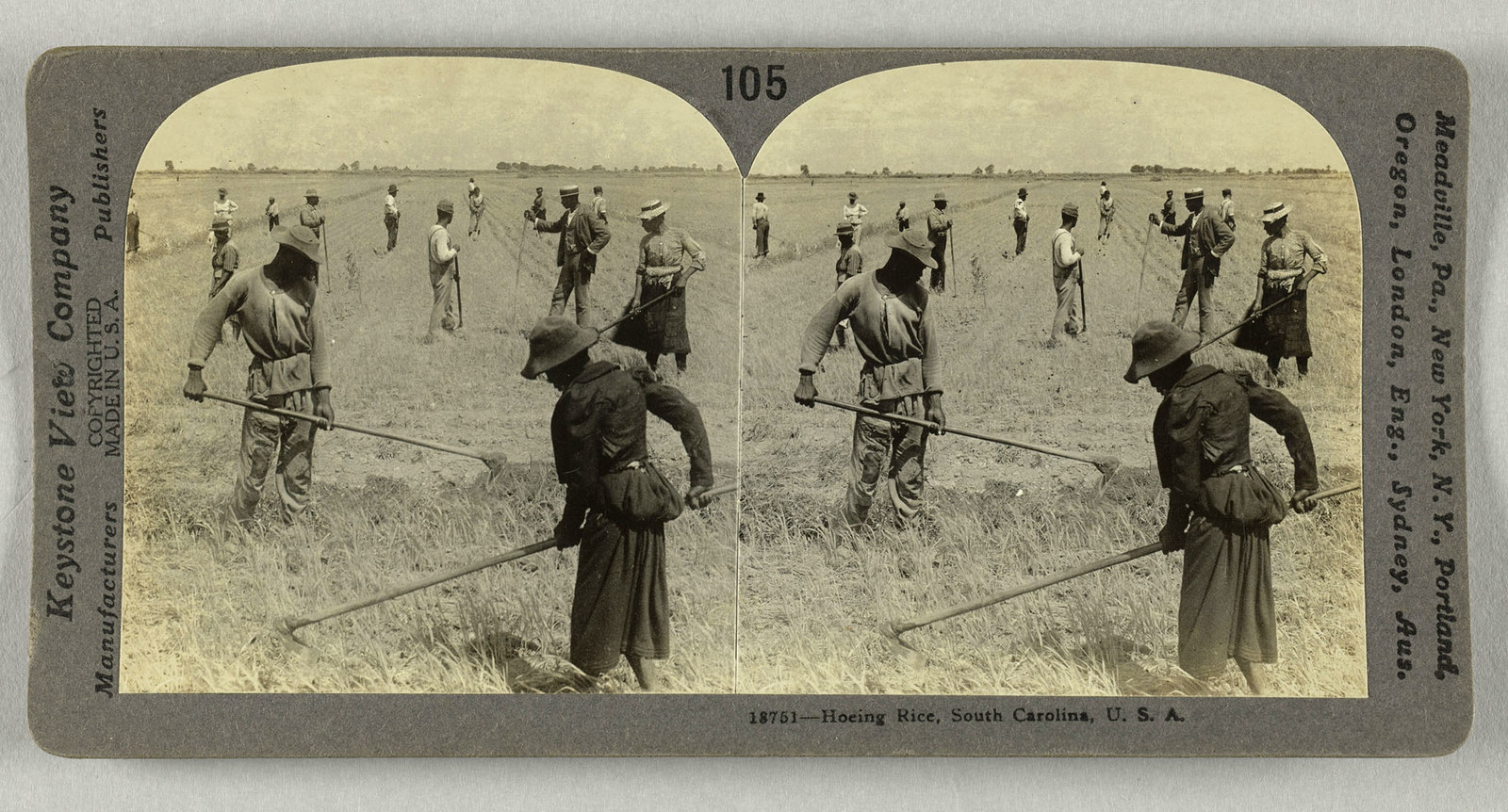

Michèle Gates Moresi: Images in this book span the 1840s through the 1920s: from the period of slavery through the Civil War, Emancipation, and Reconstruction, and through the rise of Jim Crow and white supremacy and World War I.

African Americans faced extreme challenges to their welfare, and they continuously fought for equal rights and social justice. Images of African Americans have to be viewed in these contexts. For instance, photographs taken in cooperation with the sitter [see page 41, Frederick Douglass with his grandson Joseph Douglass, 1894] were in stark contrast to racist images that perpetuated negative stereotypes of African Americans. We see that when African Americans had control of their image, they exuded a sense of pride and dignity that was relentlessly denied them by mainstream society.

How common was photography during this time, and what did exactly did being a photographer and sitting for a portrait entail?

LC: The first type of commercially available photography in the United States, the daguerreotype, “the mirror with a memory,” required at first a substantial commitment all around. For the photographer, start-up costs were high because equipment and supplies were expensive. Taking photographs also required demanding new skills. For the sitters, the process was an ordeal. Early daguerreotypes required the subject to be absolutely still for up to 20 minutes in blinding light.

Rapidly, though, this process became faster, cheaper, and easier. By the 1850s, a novice daguerreotypist could be proficient enough in two weeks to set up a business, and exposure times were down to a minute or two. Other types of photography were also emerging. Photographers adapted, and cheaper tintypes, ambrotypes, and photographic prints soon made daguerreotypes obsolete.

MGM: Frederick Douglass was among the first to recognize the power of photography, and he shared his ideas in his speeches as well as his actions. Douglass is the most photographed man of the 19th century, having sat for more than 150 portraits [see page 25]. Recognizing the import of images, he took the opportunity as frequently as possible to document his own image as a dignified, self-determined black man.

Where did the selection process begin? How did you go about making your decisions?

MGM: Working with a publication committee, we identified all the photographs in our current collection that date to the 1920s or earlier, and we each selected images we thought were most appealing for this book, with a special emphasis on 19th-century photographs. As a group we came together several times and culled to 100 photographs or so, and we continued to refine as the themes came together until we had about 60 photographs. During the process we also consulted with Professor Tanya Sheehan, who contributed an essay to this book. She selected the photographs she wanted to write about to explore vernacular photography.

Were there any challenges in organizing this book?

LC: One challenge was deciding what to include. For a young museum, the NMAAHC has an impressive early photography collection, and there were so many photographs we loved but were not able to fit into the book.

Another challenge was deciding how to organize the photographs in the book. From the beginning, we knew that we wanted to explore the roles photographs played in black life, but the roles turned out to be as complicated and messy as life itself. In the end, we settled on six themes that exemplify the use of photographs in this early period. Many photographs were used in a variety of ways, but for each photograph in the book, we chose a single way it was used to illustrate one theme.

MGM: One of our biggest challenges was how to deal with really difficult images: demeaning photographs that reinforced stereotypes and photographs documenting violence against African Americans. We considered leaving them out, but after discussing our options with our director, Lonnie Bunch, we decided that we had to include them because they represent painful aspects of American history that are often ignored, forgotten, or denied. While overall the book celebrates black life and achievement, and the power African Americans gained in creating and commissioning their own images, we also wanted to be honest about the challenges African Americans faced and how photography was often used against them.

Was there a particular image or story behind an image that really had an effect on you?

MGM: Perhaps the Harriet Tubman photograph. We are honored to have this early photograph of Tubman, the earliest known image of her, in the museum’s collection, and jointly owned by the Library of Congress. Since it came to us as part of a larger album owned by Emily Howland, we chose to feature the story of the album in the section of the book called “Preserving Memories.”

That Howland collected this image for her album is important because while Tubman is such an icon in the American imagination, and particularly for the African American story, people may be surprised to learn that Tubman was also a great hero in her own time. She was revered by abolitionists, and Howland came from a family engaged in anti-slavery activities. Howland’s photo album holds portraits of various figures important to her, rather than images of family, so it was probably a keepsake album. So it’s a great opportunity to share with readers a broader story of how Tubman had a presence and meaning in her own time for people who admired her.

How is this project personal for you?

MGM: I’ve been working on various aspects of the museum’s photography collection for a long time, so contributing to this latest volume was especially meaningful to me. In particular I am pleased with the opportunity to ask people to look at these early photographs with new questions and to consider multiple meanings and purposes, for these images, then and now.

LC: Who doesn’t love photographs? Especially of people. I am fascinated by old photographs. I live in a different place and time, but I feel a connection to the sitters in these images because they are people. I want them to be recognized and remembered. Working on this book also increased my understanding of the complicated relationship between race and photography, not only in America’s past but also in its present.

What do you hope people will take away from this book?

LC: I hope that they will take away an appreciation for the African Americans represented in this book, whether in front of or behind the camera, along with a recognition of the power of early photography.

MGM: I hope that people will feel a connection to the past and recognize the power of photography and images, even if they are more than 100 years old. Especially in regard to photographs of unidentified people, we can nonetheless still learn something about people’s experiences and in a way recover a past that was too often ignored and misrepresented.