Lee Miller, who lived in an era that often defined the careers of women as secondary to those of their male colleagues, defined her own legacy with a fiercely independent attitude and a stiff defiance against the patriarchy.

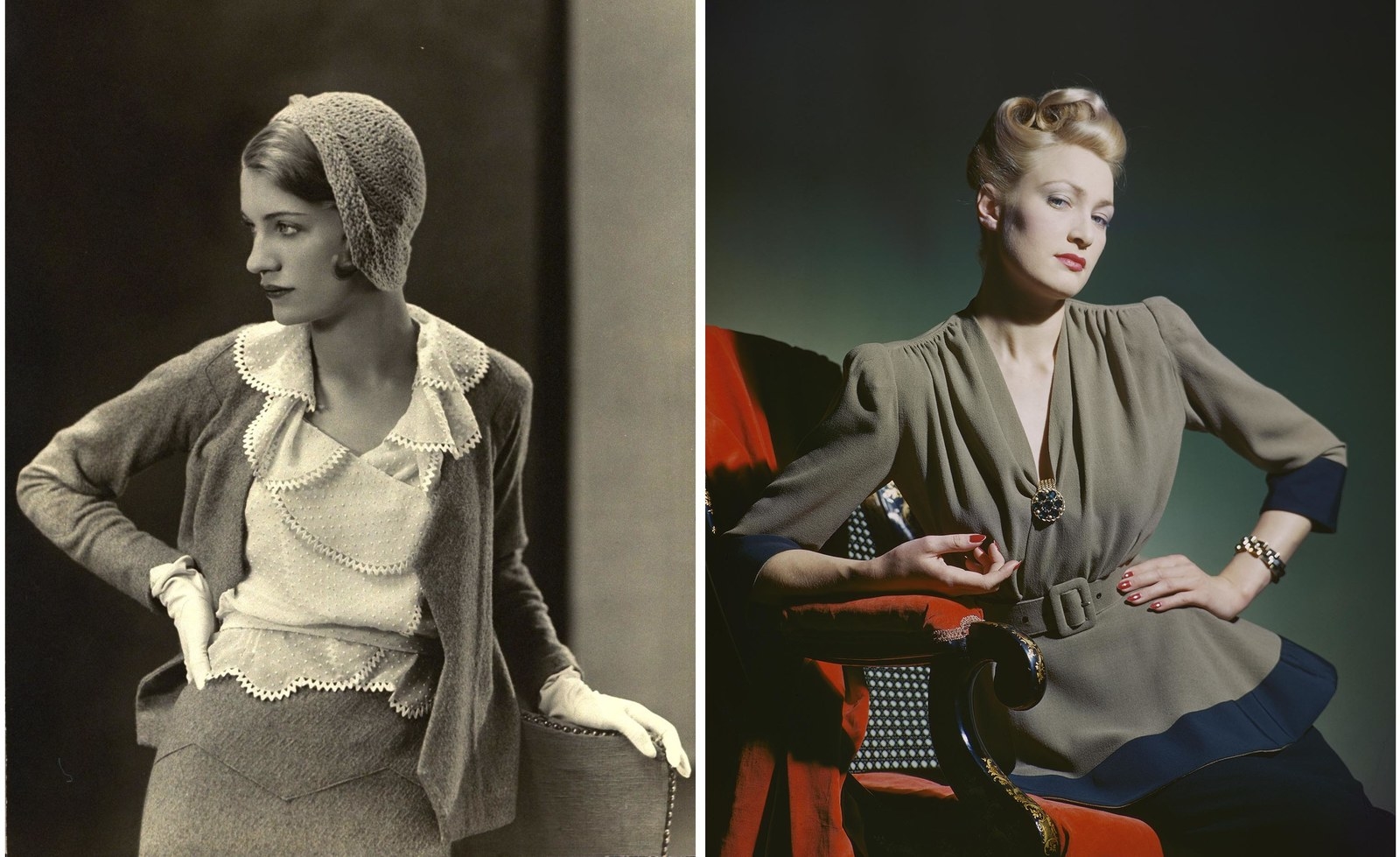

Her career began at age 19, when Miller was nearly struck by a speeding car in New York City before being pulled to safety at the last moment by Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue. Nast was immediately taken by Miller's strong sense of style and offered her a job as a model for his magazine. With her foot in the door of the fashion industry, Miller quickly gained a reputation as an excellent photographer and brought those skills to Paris in 1929, where she crossed paths some of the most important artists of the 20th century.

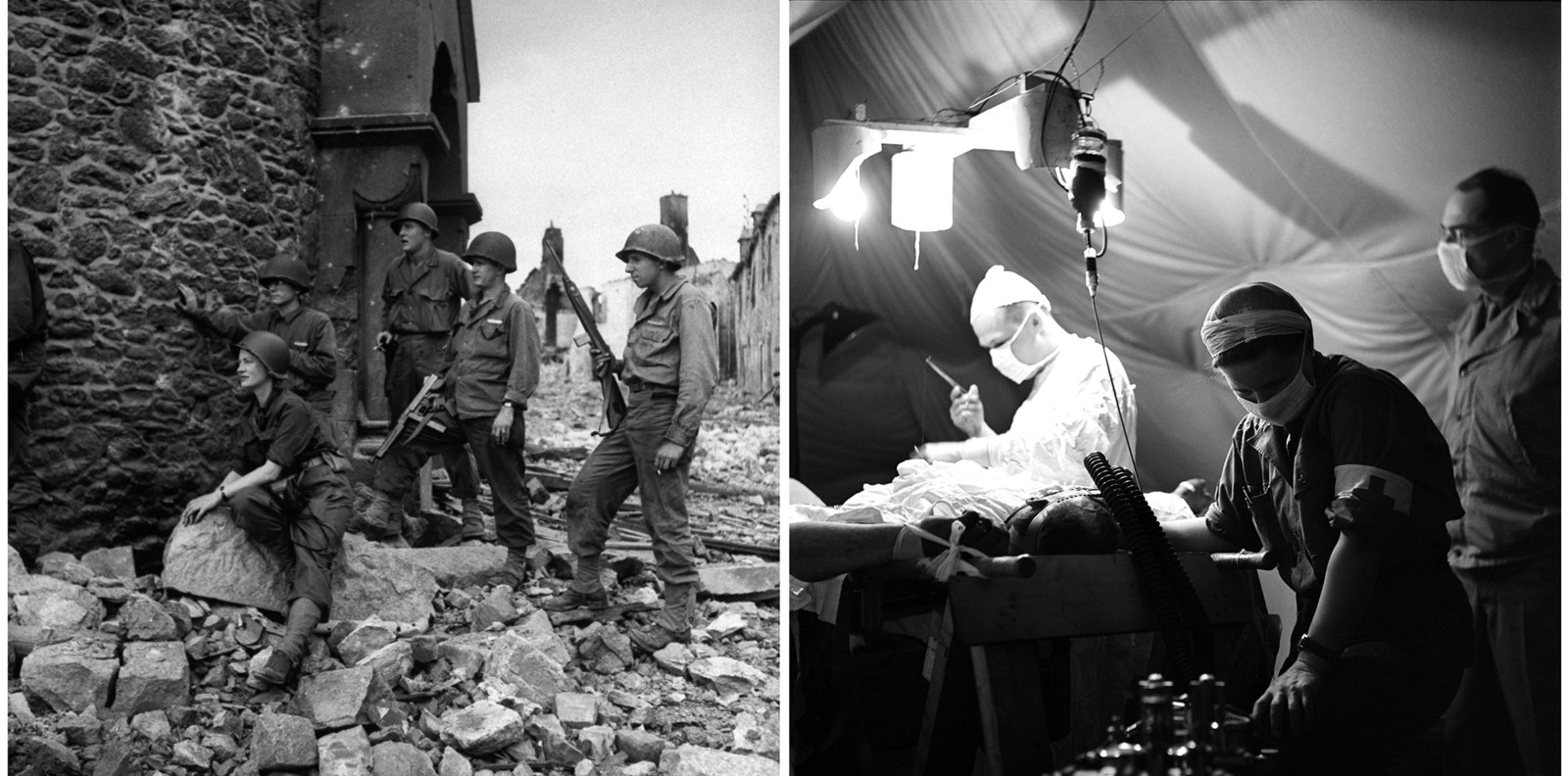

At the outbreak of World War II, Miller was granted the unique assignment of being the official war photographer for Vogue. Her work in Europe during this time was striking and unafraid, documenting some of the worst aspects of the war, including the Blitz and the concentration camps at Dachau and Buchenwald. She continue photographing after the war, though she had PTSD and depression before dying in 1977 from cancer.

Here, Lee Miller's granddaughter and the codirector of the Lee Miller Archives, Ami Bouhassane, speaks with BuzzFeed News on Miller's lasting legacy.

Who was Lee Miller as you know her?

Ami Bouhassane: Lee Miller was born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1907 — she was a woman of many lives and mistress of her own reinvention; model; surrealist; portrait and fashion photographer; war correspondent; and gourmet cook. She did everything wholeheartedly, with astuteness and an imaginative flair.

She was undeterred in the face of adversity, ranging from her childhood trauma to not accepting the inequalities dictated by society and to learning to live with mental health difficulties such as postnatal depression and PTSD, which she suffered from following what she witnessed during World War II.

She’s also my gran and one of my heroines.

How true is this tale of Miller's fashion career beginning with Condé Nast saving her from an oncoming vehicle?

AB: As far as we know — it is true, he did save her. He had noticed her because she was dressed in Parisian fashion, having not long before returned from Paris where she had studied theatrical lighting.

However, we believe she added to the myth of him being completely responsible for her career as a model. Mostly because in those days, a woman openly admitting to networking for a career could have been easily misinterpreted as calculating or manipulative. To credit her rise to becoming a top model to luck was a much easier, more acceptable story.

She had already been moving in the fashion circles socially and had known the fashion photographer Edward Steichen for many years. She also knew Georges Lepape at least a couple of months before the Condé Nast story happened. Lepape was the illustrator who drew the iconic image of her when she first appeared on the cover of Vogue in March 1927, and Steichen went on to photograph her a lot for Vogue.

Whilst Condé Nast played a key part in launching her career as a model, it’s hard to determine exactly how much of her success can also be attributed to the contacts and experience Lee already had.

What were some of the challenges that women faced during this time, particularly in the realms of art and photography?

AB: It was tough to be a career woman in her time, she used the shortened version ‘Lee’ of Elizabeth, her birth name, as her professional name because it was androgynous and meant that as a photographer those who only knew her work would not be prejudiced against her gender.

As a war correspondent during World War II, her accreditation was also different. Women were thought to be weaker and not permitted to be under fire. They were expected to report from safer zones such as casualty clearing hospitals.

Miller is noted as being the official war photographer for Vogue, a title that sounds bit odd today — can you talk a bit about this period of her life and her motivations during this time?

AB: It was odd!

Becoming a correspondent for Vogue was driven by her — she had been working freelance and volunteering for British Vogue and other magazines since moving to Britain. Then war was declared in 1939. Out of personal interest, she began covering the bomb damage as well as the war efforts and everyday lives of British civilian women.

British Vogue had to justify its paper rationing to the government and to do so was charged with trying to make war efforts fashionable. It was Life magazine photographer David E. Scherman who suggested Lee become accredited to the US Army, which she embraced as an idea.

Having the pass gave her access to cover the women in service’s war effort that previously she had not be able to. She covered the WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service), the Women’s Land Army, the ATS searchlight battery, and other such services in Britain. Not long after D-Day she went to Normandy to cover the war in Europe. Her second assignment in Europe was supposed to be in a safe zone away from the front, but instead, British Intelligence had got the information wrong and when she arrived, the battle of St. Malo was still raging.

All the male war correspondents had been sent to cover known battles; she found herself the only reporter there. She stated later in an interview, "What’s a girl to do when a battle falls into her lap?" She violated the terms of her accreditation as a woman and covered the combat. As a consequence, she was later put under house arrest, but this did not deter her from catching up with the US 83rd Division again and covering further battles.

Is there a particular image or story from her life that really stands out to you as a perfect representation of who Lee Miller was?

AB: That’s a really tough one — she took 60,000 pictures and wrote thousands of pages of manuscripts! She also reinvented herself many times. Then there’s her razor-sharp wit, which still has me smile when I think of some of her stories and side comments in her manuscripts and her quirky sense of humor.

One of her most famous images, "Portrait of Space," used to mystify and fascinate me as a kid. I genuinely thought the title meant it was in space and she had been to the moon. Why not? She’d done so much else! I used to stare at it, imagining astronauts bouncing around in the landscape. It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I realized it was an image of escape, adventure, and had many depths to it.

My respect and love deepened for the picture, which by then was like an old friend, when I found it had been published in surrealist publications in the ’30s and inspired other artists to create other works, such as René Magritte’s Le Baiser.

What do you hope people to take away from her images today?

AB: A desire to look at things differently, to find the marvelous in the everyday and celebrate it. I hope Lee Miller's story inspires others to have strength in the face of adversity, a passion for truth, justice, and freedom, and to be undeterred.