Love photography as much as we do? Sign up for the BuzzFeed News newsletter JPG for behind-the-scenes exclusives from renowned photographers and our hard-hitting photo stories.

This Pride Month has been unlike any other in the 51 years since the 1969 Stonewall Riots, an event that sparked an era of LGBTQ activism and set the tone for decades of protest to follow. Pride celebrations in recent years have straddled a line between party and protest, but this year against the backdrop of mass demonstrations against racial injustice and an ongoing global pandemic, Pride celebrations have since returned in force to their roots of political dissent.

In Brooklyn, thousands of demonstrators have taken to the streets to advocate for the equal treatment of Black transgender people, a population that often goes underrepresented in LGBTQ activism and is especially vulnerable to violence. Similar marches have played out in major cities across the US in solidarity with the Black Trans Lives Matter movement.

These marches come amid a landmark decision by the Supreme Court against discrimination in workplaces on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. While the court ruling marks an undeniable victory for LGBTQ people in the US, images of protesters in white marching by the thousands are a clear signal of the enormous distance still left to overcome in the fight for justice, equality, and visibility for the LGBTQ community.

BuzzFeed News spoke with the New York Public Library's assistant director of collection development, Jason Baumann, who coordinates the library's LGBTQ initiatives. Here, Baumann discusses the vital role of protests in the advancement of LGBTQ rights, dating back to the Stonewall Riots in 1969, and the lessons to be learned from these pivotal moments in LGBTQ history.

How have protests been essential to the advancement of LGBTQ civil rights?

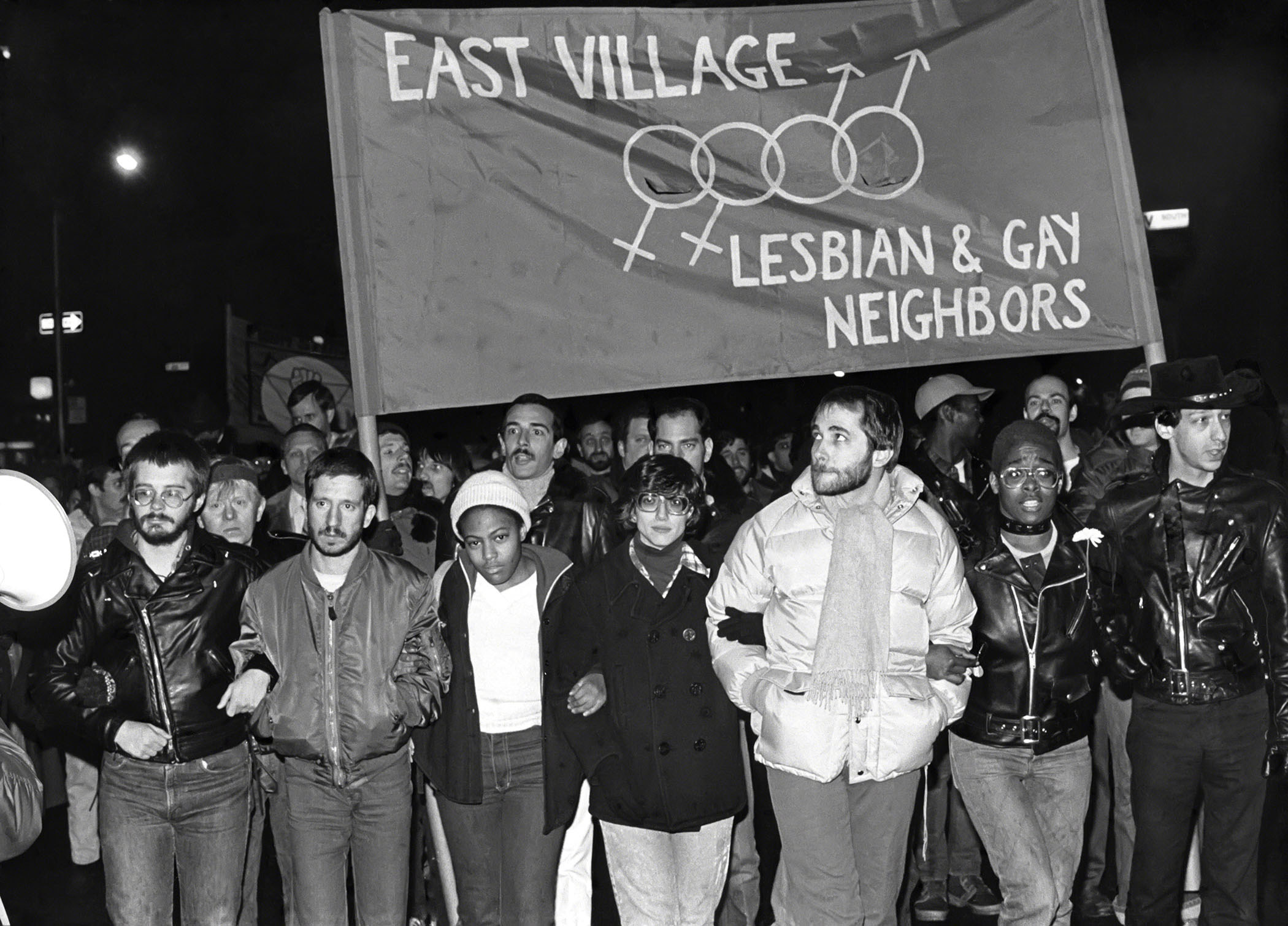

For us LGBT people, the act of protest has always been about us taking public space. It’s been a way for us to both signal to authorities that we have political power and agency, but also for gay, lesbian, and transgender people to see that they are a community.

How have these protests changed over the years?

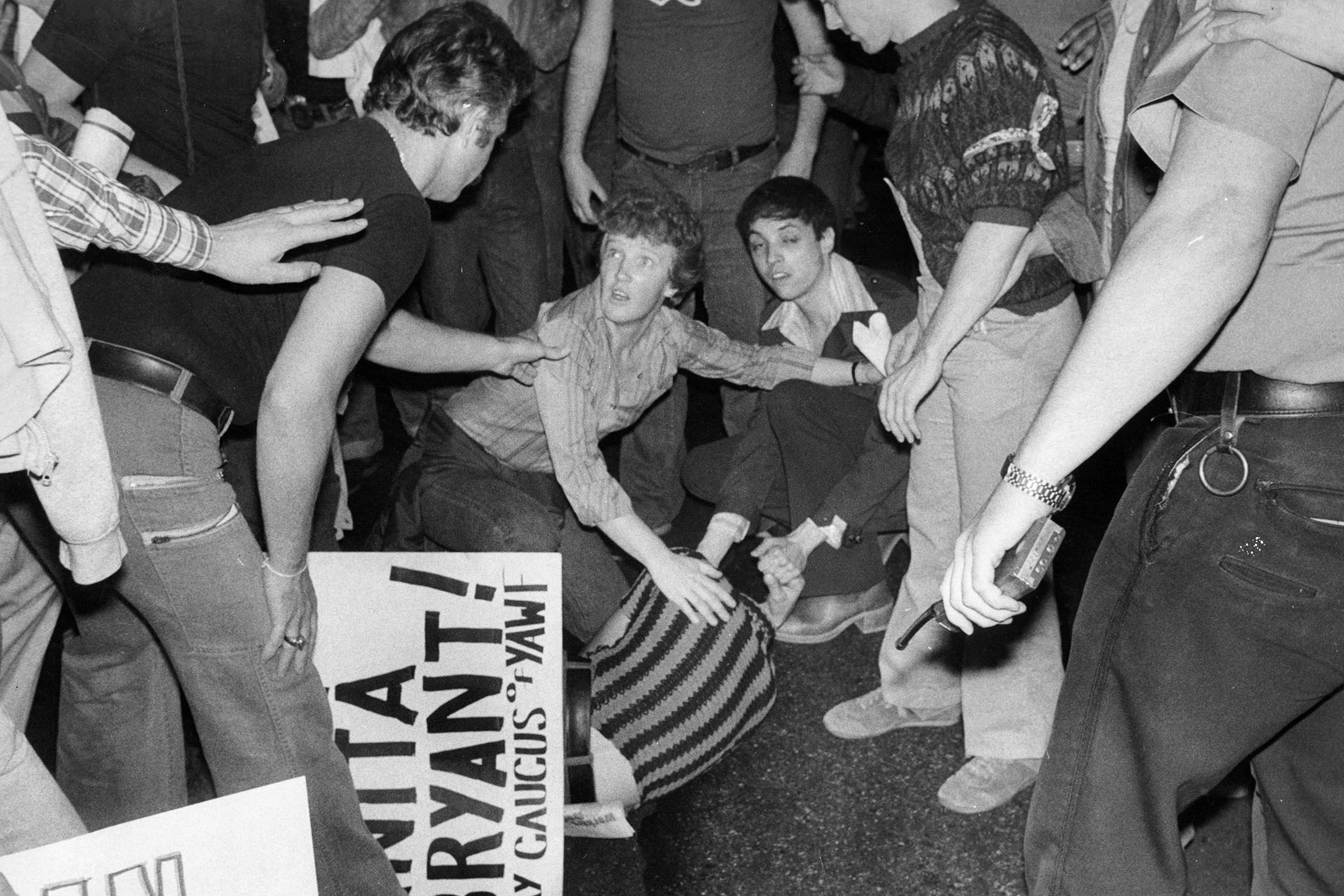

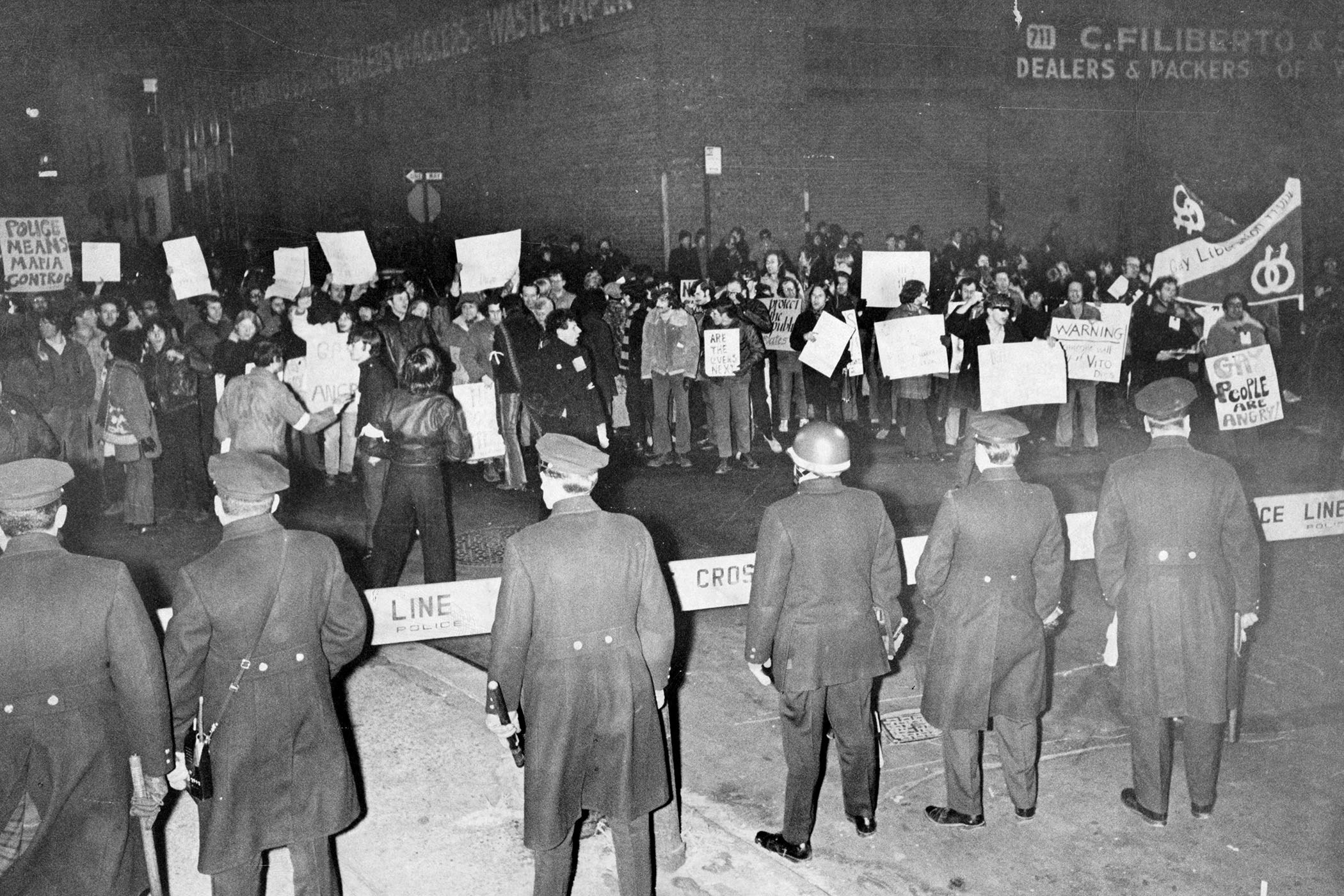

Really, LGBT protests in public really started in the mid-1960s, but they were small affairs. One of the first ones in New York was at the Selective Service Agency, and maybe there were about 10 people there who were willing to be out as homosexuals. It’s important to realize that being gay or lesbian was a crime in the United States up to 2003, and it was also thought of as a mental illness that [people] could be institutionalized and subjected to electroshock treatment for. So for these people to publicly make a statement that they were gay or lesbian was this enormous risk for them — they could have lost everything.

Part of the statement that was being made in these early marches was the refusal to be an invisible minority. For other minority groups in the US, there wasn’t an issue of “coming out” to have to show our numbers, so this was a very dramatic thing in LGBT politics.

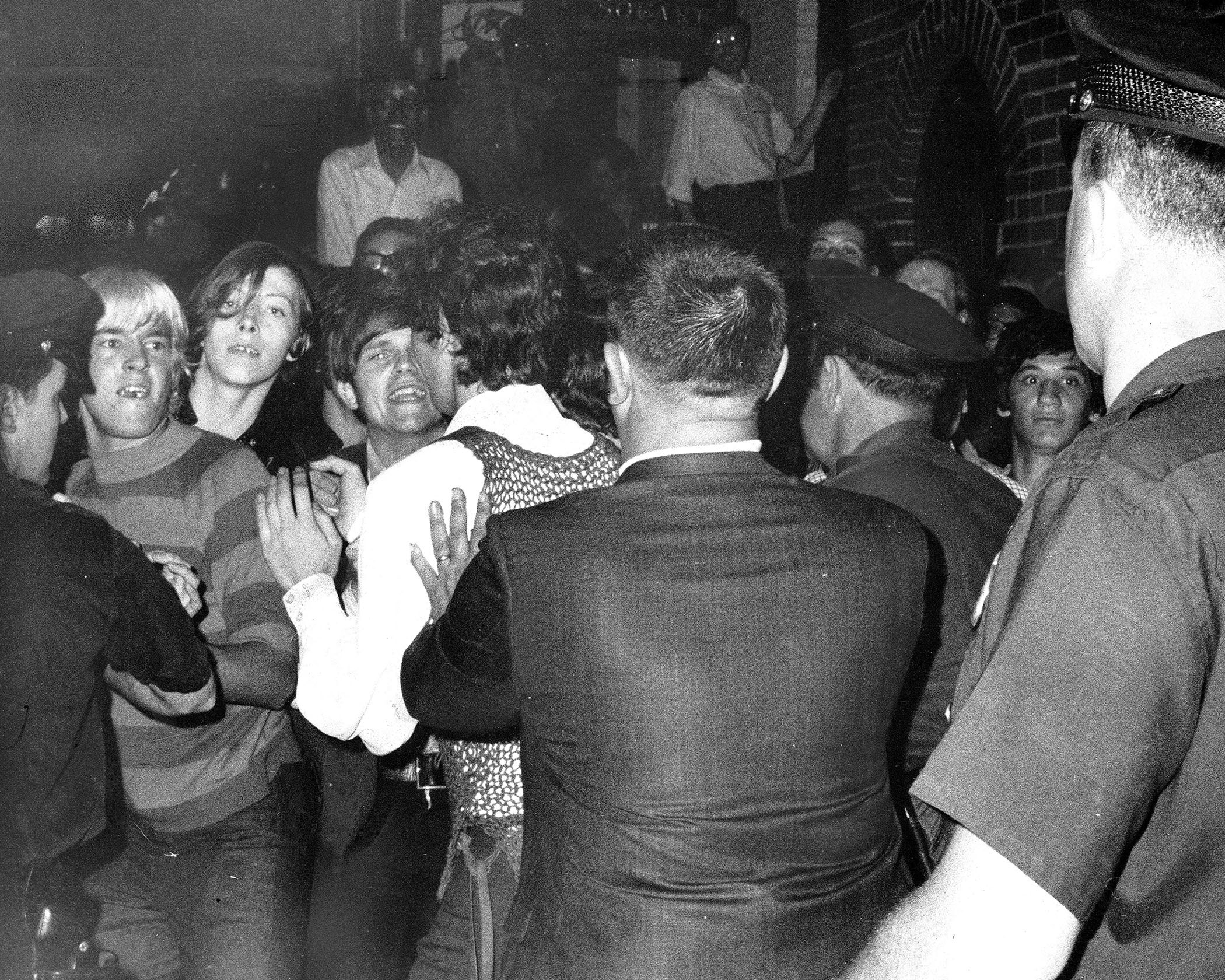

The events at New York City’s Stonewall Inn in 1969 were a watershed moment for LGBTQ activism and are often described as a “riot” — do you agree with this description?

It’s important to note that the people who participated in Stonewall at the time categorized this event as a riot. Because there was widespread unrest in the US and because there were very similar kinds of demonstrations against racial oppression occurring, the people who participated in Stonewall, I think, really wanted to align this moment with what was happening elsewhere.

It’s important to see that there is a very strong link between the African American civil rights movement and the LGBT civil rights movement. The LGBT civil rights movements have been incredibly inspired by the African American fight for civil rights, so in the same way when LGBT activists talked about Stonewall, they wanted to show that what happened at Stonewall was also a fight for equality.

It’s true that participants disagree about what to call this event. Some of them believe that there was violence, but that it wasn’t violent enough to qualify as being a riot, and some feel that there is a politics to calling these kinds of things riots — in the same way that many historians of African American history also feel like the racial uprisings and disturbances in the 1960s also shouldn’t be called riots, but rather protests, demonstrations, or rebellions. That said, the participants thought about this event in many different ways and there’s a politics to all of this language that I do not think is resolvable.

What lessons can be learned from these demonstrations?

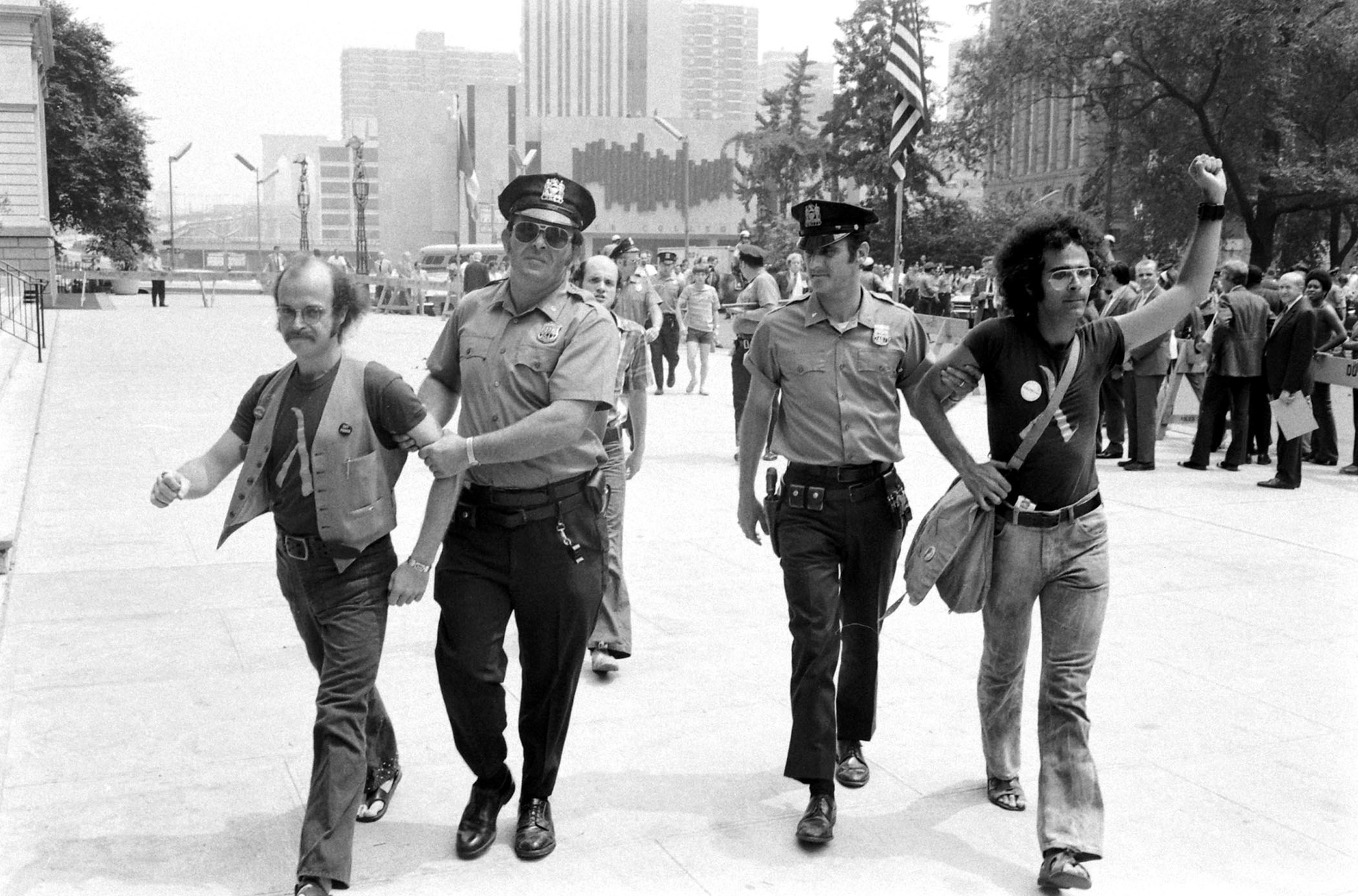

The thing that strikes me the most from those demonstrations of the ’60s and ’70s is the duality of these events. These demonstrations were designed for both the media and for a show of political strength — these people were trying to make a point to elected officials. But on the other hand, what these protests do is draw people together as a community.

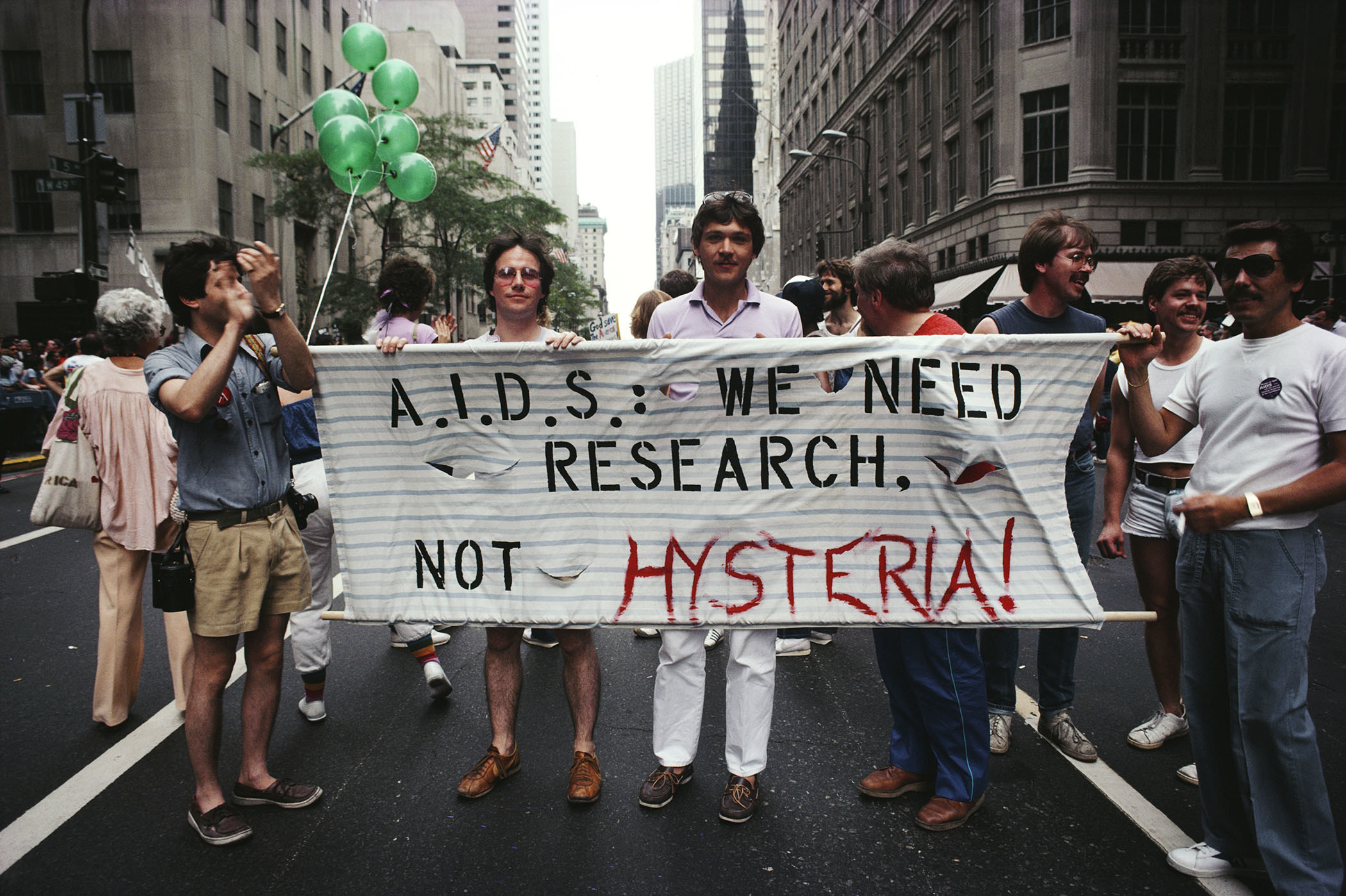

I remember myself as an activist with ACT UP in the late ’80s and ’90s, there were demonstrations we did that may not have gotten the same kind of media attention or made an impact on elected officials, but it drew us together as a community. So I think that both of those things are happening at the same time — building a political community and the message that you’re putting across.

These are the tactical lessons that can be learned if you look back over the history of LGBT activism — to really think about what is the messaging, the activity as a whole, and even the theatrical element to a demonstration and not to underestimate how important drawing together a political community can be.