Before the United States took "one giant leap for mankind," it was a few brave canines from the Soviet Union who made history in space and paved the way for humans to journey into the cosmos.

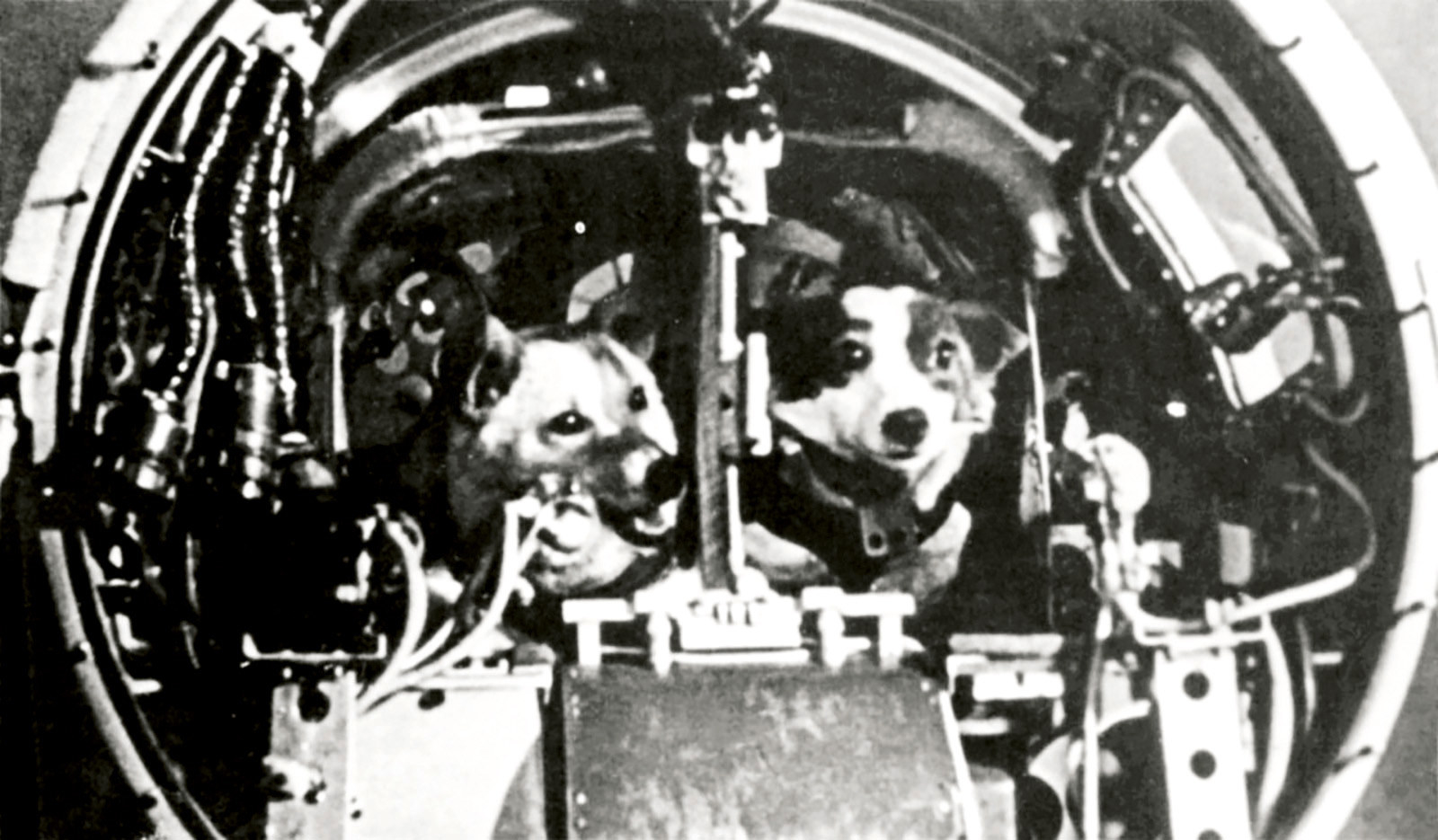

Space Dogs: The Story of the Celebrated Canine Cosmonauts, a new book by renowned photographer Martin Parr and writer Richard Hollingham, explores the rarely told story of the Soviet dogs who were sent into space during the mid-20th century as precursors to manned spaceflight. Dogs like Belka and Strelka — the first to make the round trip — were sent into space to better understand how a living organism can survive in a zero-gravity environment. Upon their return, these tiny astronauts were celebrated as heroes and, as this book reveals, reached a level of celebrity that rivaled the Beatlemania of subsequent years.

Here, Hollingham shares with BuzzFeed News the fascinating and heroic story of how of these canines made the journey to where no dog — or human, for that matter — had gone before.

What made dogs the ideal candidates for early space travel?

Richard Hollingham: You have to understand that people had no idea whether humans could survive in the weightless conditions of space. That was the big question.

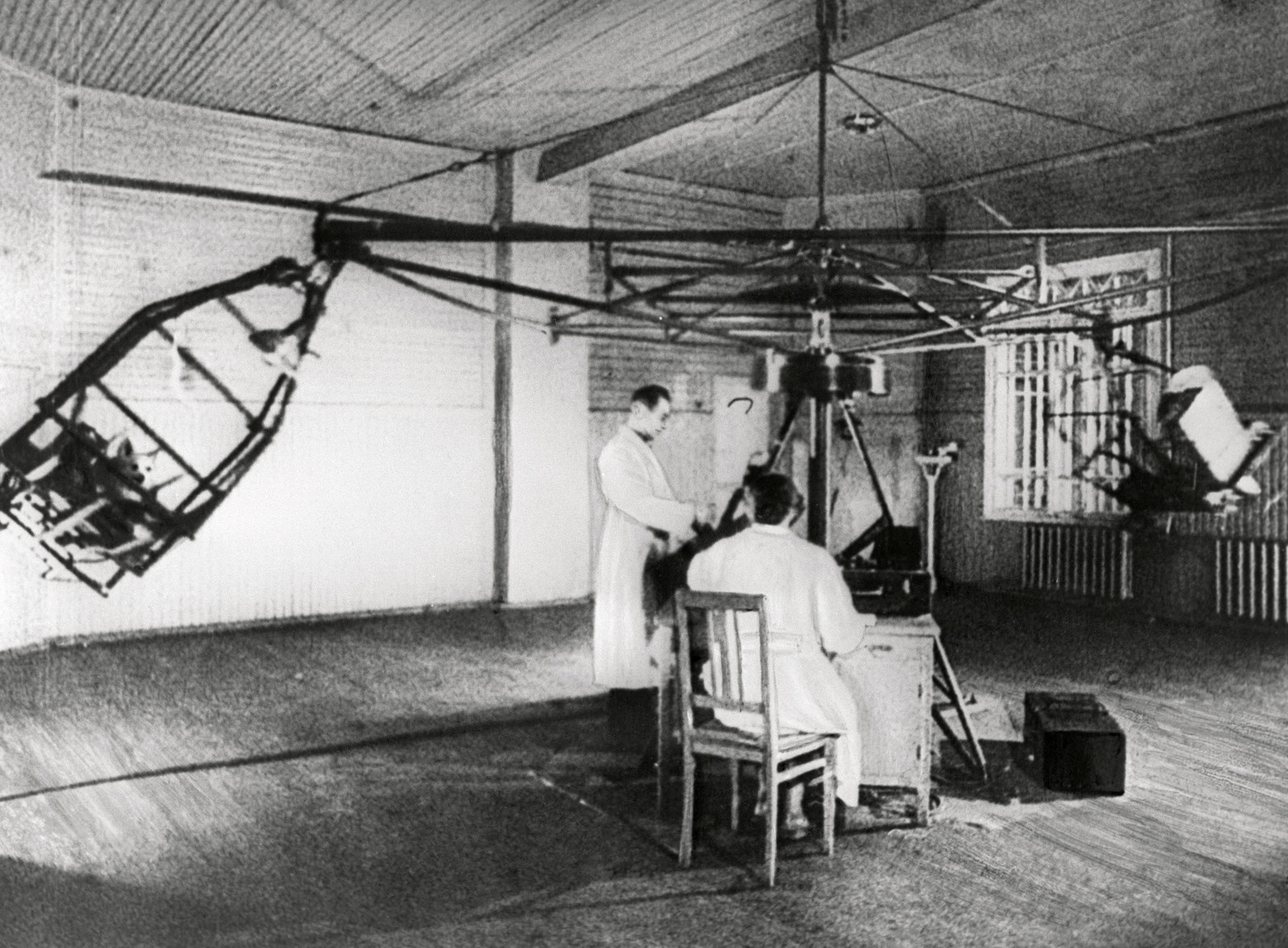

There were thoughts that the accelerations would cause hearts to explode, that you’d be unable to breathe and that the whole metabolism would shut down in weightlessness. Some believed that without gravity, given that we’ve evolved as creatures who live in this perfect 1G environment, that our bodies would just fail.

Almost immediately after World War II, the US, Britain, and the Soviet Union started experimenting on captured German V-2 rockets and building on their own rocket technology. It didn’t take long for both sides, independently and without knowing what the other was doing, to begin putting animals in these rockets.

Initially, you might fly insects — or you might fly mice to start with, like the Americans did. All of these animals came back unscathed, so the next step was to start understanding the effects of space on something a bit nearer to us. The Russians, who had a history of using dogs in scientific experimentation, turned to dogs as a way of doing this sort of work.

The first flights took place in the late 1940s of Stalinist Russia, during the first evolution of the Soviet versions of the V-2 rockets. They essentially took apart the V-2 rocket, put their own rocketry knowledge into it, improved it, and started flying dogs in the compartments of the top where the bombs would have been situated.

Were any of these dogs killed?

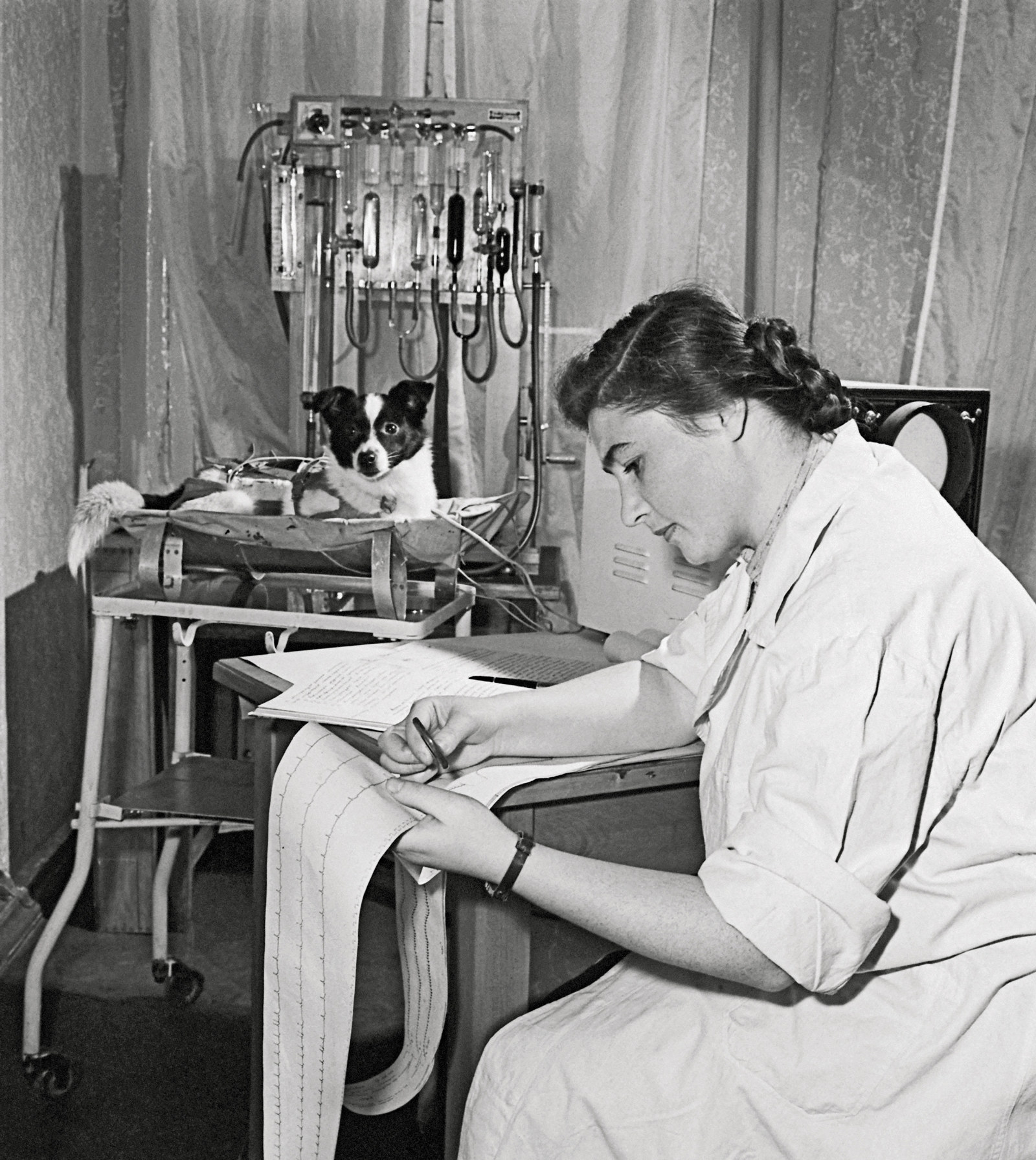

RH: The intention was to never kill dogs. They captured these dogs as strays on the streets of Moscow. Usually, they’d use female dogs because they didn’t need to cock their leg to urinate. These were quite confined capsules, so that was easier. The dogs were also well looked after — they were loved, I think it's fair to say, and were put through very extensive training, given little space suits, and were climatized for this environment.

But inevitably, a good deal of them died. A rocket might explode. Reentry might fail. It’s difficult to give an accurate number on the deaths because we don’t have figures on all the dogs that went into space, but around half of them didn’t make it. But that was never the intention; there were very few instances where they knew the dogs were going to die.

How were these dogs received by the public when they returned from space?

RH: What’s really interesting is that the one dog they knew who was not going to come back was Laika, who was the first animal ever in orbit. After they launched Sputnik 1, the first satellite, [in 1957,] they had the capability of sending a dog into space, but they did not have the capability of bringing her back. So they knew when they closed the capsule to Sputnik 2 that Laika was going to die.

The intention was that she would die peacefully in a capsule and without pain. Unfortunately, as it happened, the capsule overheated and she probably did die a fairly painful death. The reason I mention this is because of the way Laika is represented in culture after that — she's often depicted in a stoic manner. It’s almost like she’s representing the motherland. All the pictures are quite noble and serious.

But when you get into Belka and Strelka, the first dogs to orbit the Earth and return safely to the ground [in 1960], everyone just goes crazy! You’ve got Christmas decorations, cigarette packets, badges and clocks, these playful spaceships, saltshakers, and watches. They just became massive celebrities.

Are animals still sent to space today?

RH: What’s really important here is to remember that these dog flights were not in vain. Everything from Laika to Belka and Strelka, to even later dogs — everything learned absolutely fed into the human space program. All astronauts today owe what we know about surviving in weightlessness ... to inadvertent pioneering of these space dogs. That said, nobody flies space dogs anymore; no one flies chimps anymore, either, which was what the US did, though mice and insects are still often used in space.

The reality is that most of the experiments now are done on humans. We had Scott Kelly doing a full year on the International Space Station recently. Every astronaut in space is having their blood taken, having muscle biopsies, and is engaging in studies. So the experiments have now shifted to doing actual research on humans in space, but we still owe a huge debt to the pioneering work of these space dogs.

To pick up your copy of Space Dogs: The Story of the Celebrated Canine Cosmonauts, visit laurenceking.com.