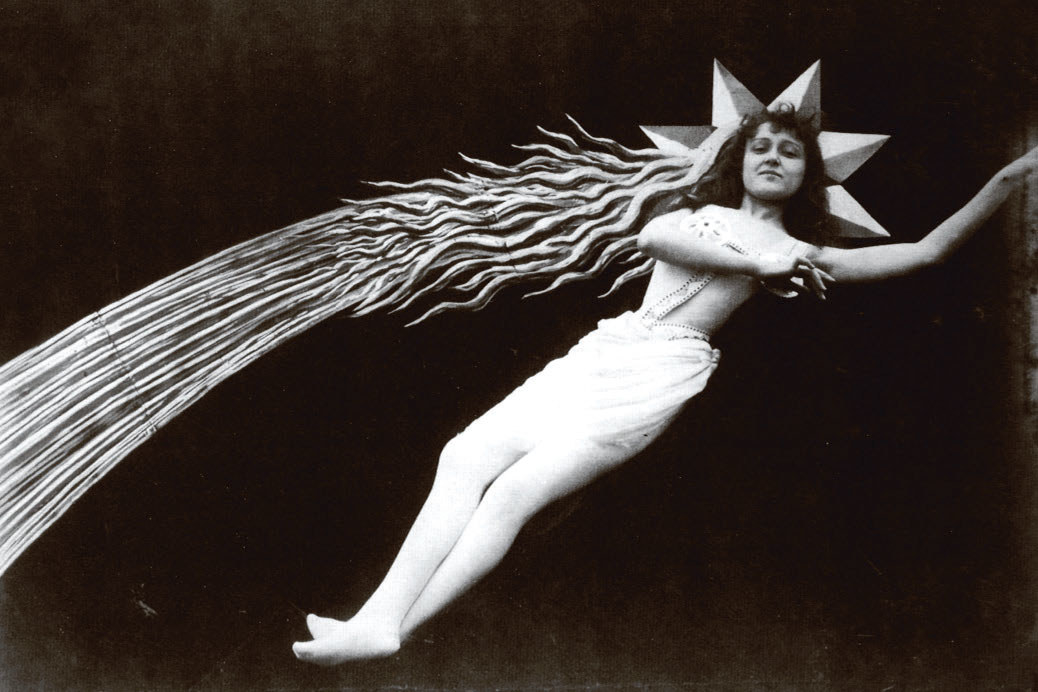

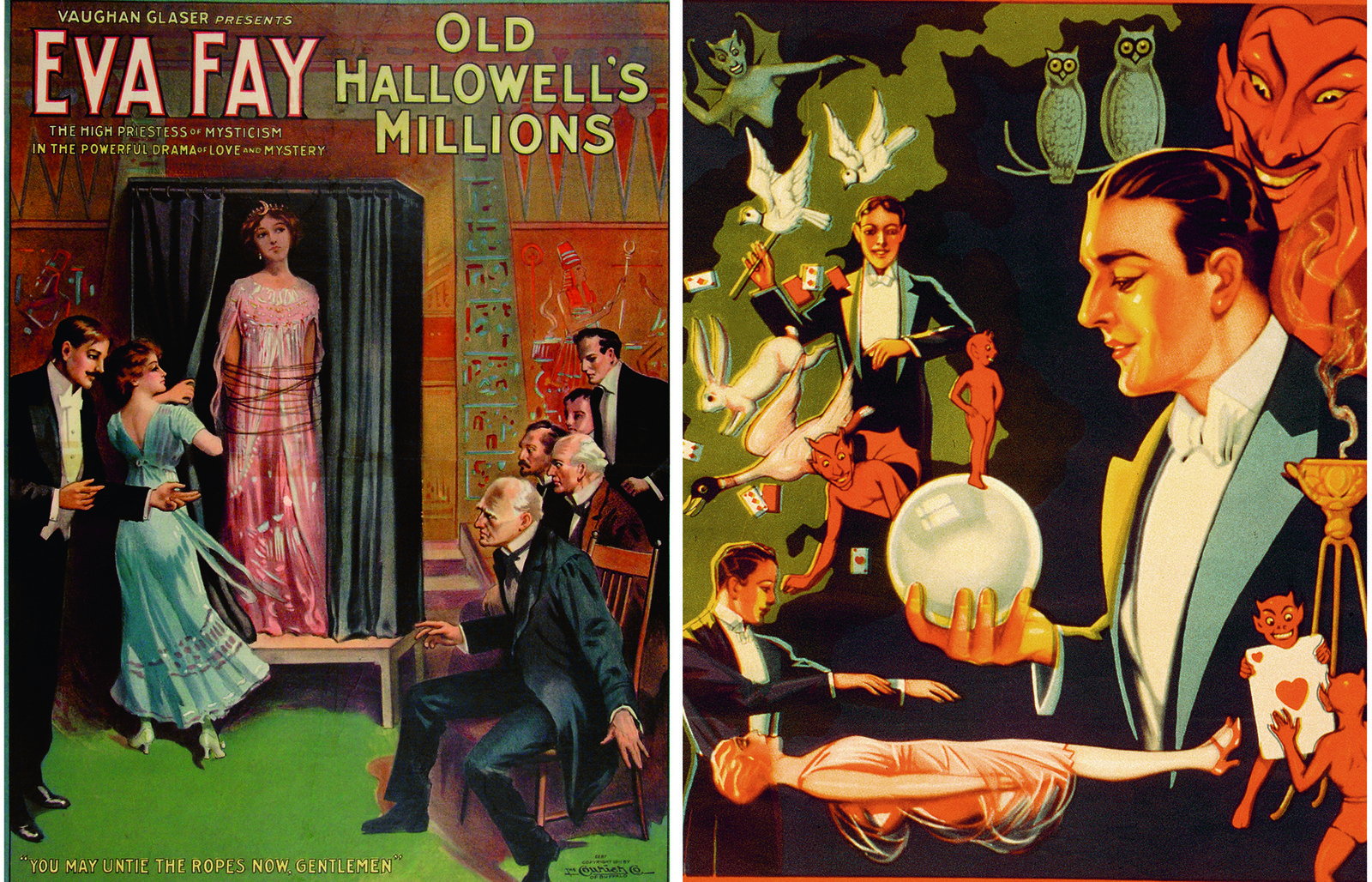

Throughout history, illusions and spectacles have entranced people into believing in the paranormal. Magicians, psychics, and mystics have long employed tricks of the senses to leave us amazed and curious of the unknown. As science and technology advanced at the turn of the 20th century, illusionists concocted new and innovative ways of tricking their audiences by blurring the line between science and the paranormal.

One person who is uniquely qualified to recount this history is Matthew L. Tompkins, a former professional magician who recently completed his doctoral studies in Oxford’s experimental psychology department. His new book, The Spectacle of Illusion, offers a comprehensive examination of paranormal illusions since the 1800s.

Here, Tompkins shares with BuzzFeed News his expertise on the human mind’s susceptibility to illusion, as well as some curious history of the paranormal.

How has your experience as a magician informed your research as a psychologist?

Matthew L. Tompkins: My experimental work and my approach to teaching and science communication have been heavily influenced by my past experiences working as a professional magician. For Spectacle of Illusion, the focus is on how scientists have attempted to study extraordinary phenomena, and how they’ve interacted and been influenced by the work of people who practice illusions, such as magicians and fraudulent mystics.

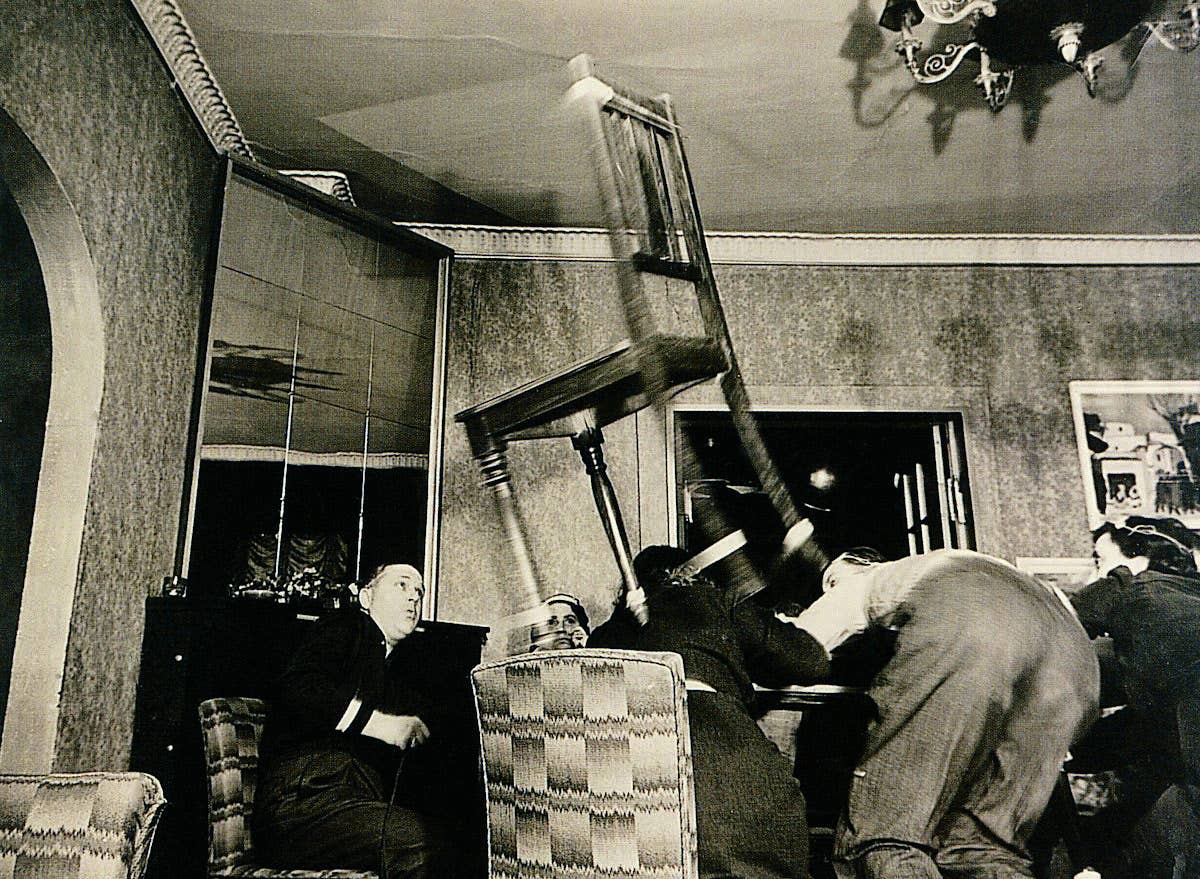

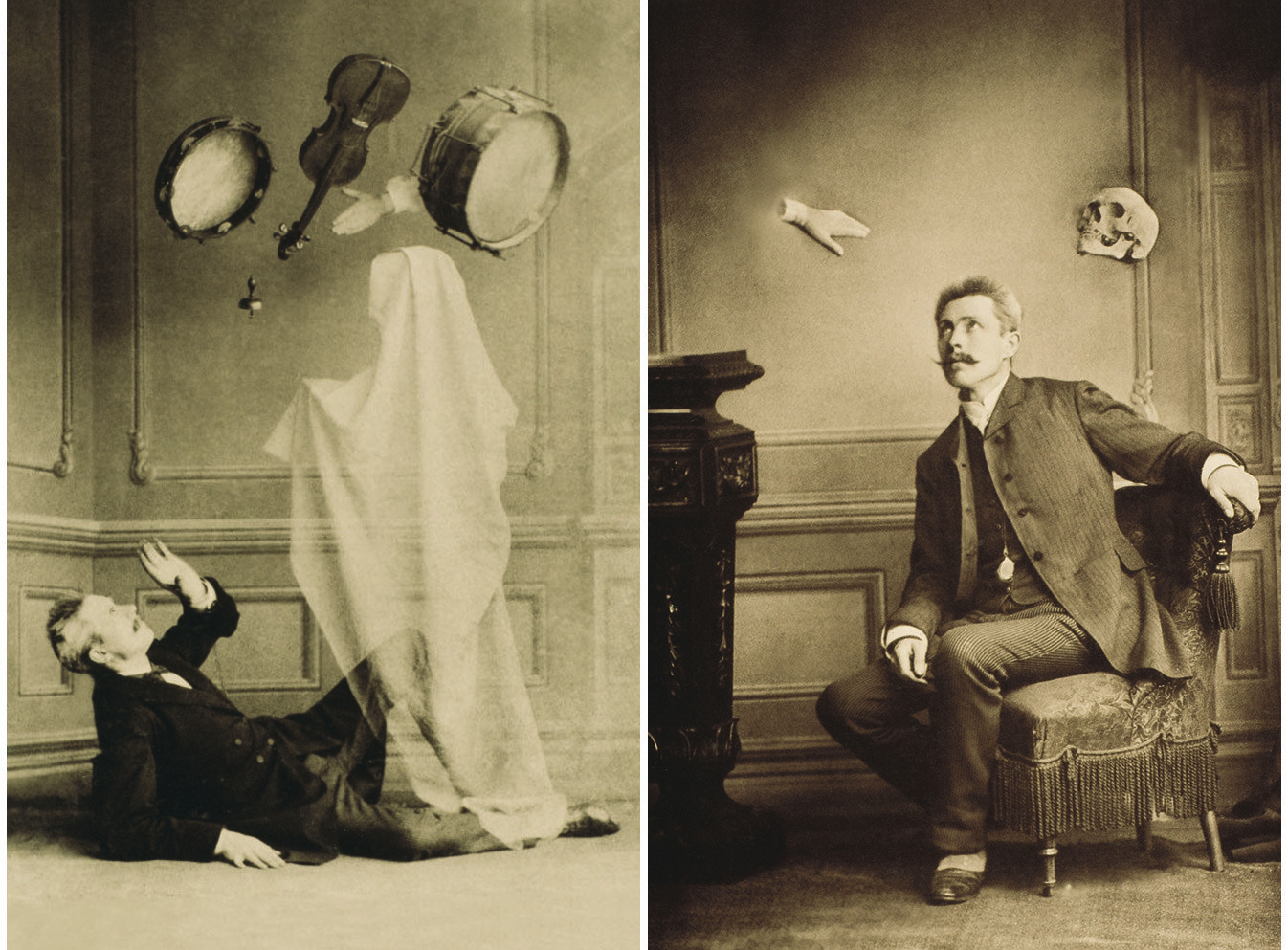

These sorts of interactions can cut in both directions. On the one hand, practitioners of illusions have directly offered valuable insights that have helped drive advances in human psychology. One of my favorite is examples of this comes from one of the earliest systematic attempts to explore the psychology of eyewitness testimony. In the late 1880s, the amateur magician S.J. Davey helped design an experiment in which he used his sleight-of-hand knowledge to stage hoax séances — the researchers were interested in how people’s recollections of the events might deviate from what actually happened. Ironically, for a study of memory reliability, this experiment itself has been largely forgotten.

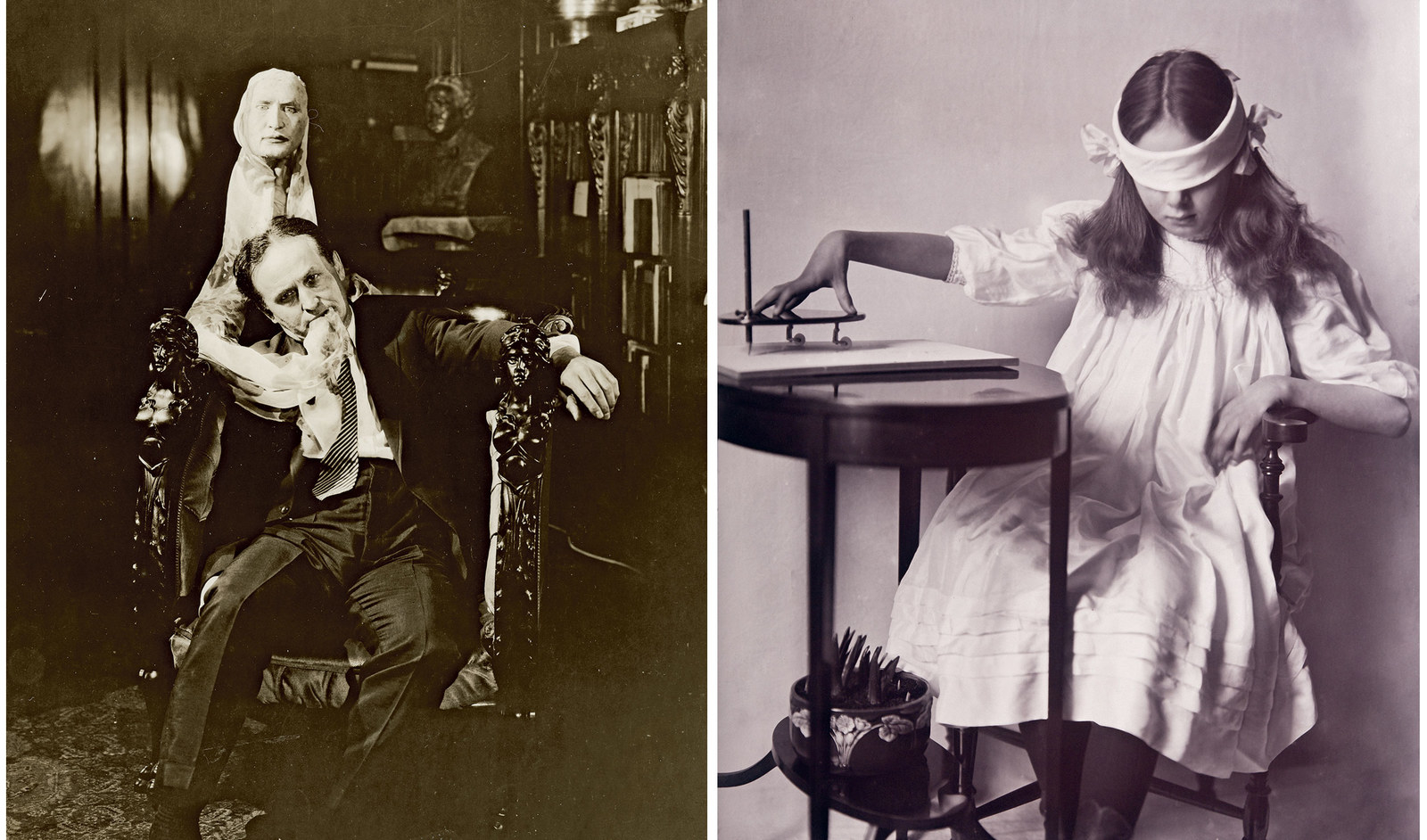

On the other hand, individuals have used illusions to conduct elaborate hoaxes that have tricked researchers into embracing false conclusions. The American spirit medium “Dr.” Henry Slade famously convinced a number of prominent German scientists to try to rewrite fundamental laws of physics to accommodate the concept of intelligent extra-dimensional spirit people.

What was it about this era that made something so obviously unbelievable today, feel so authentic back then?

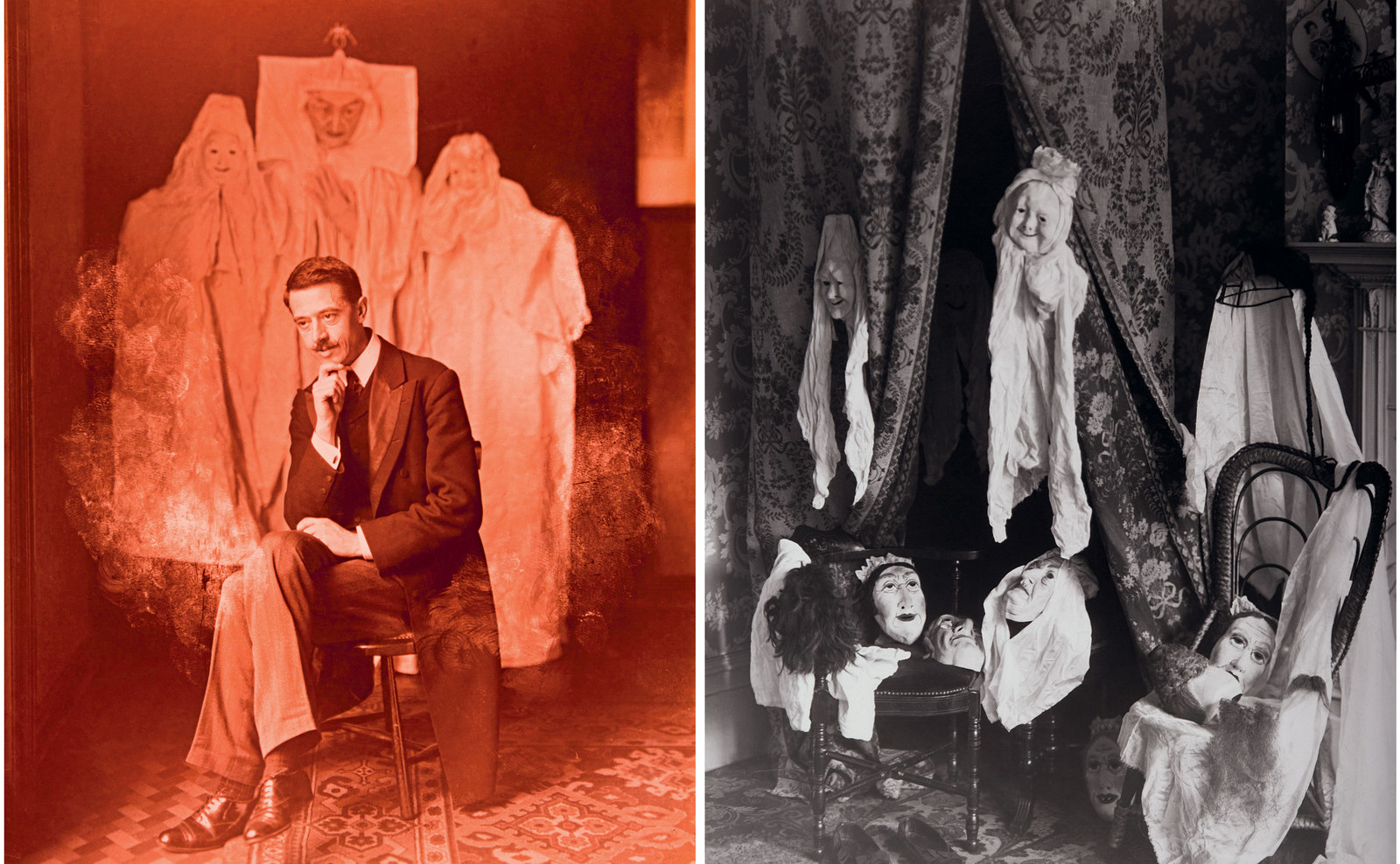

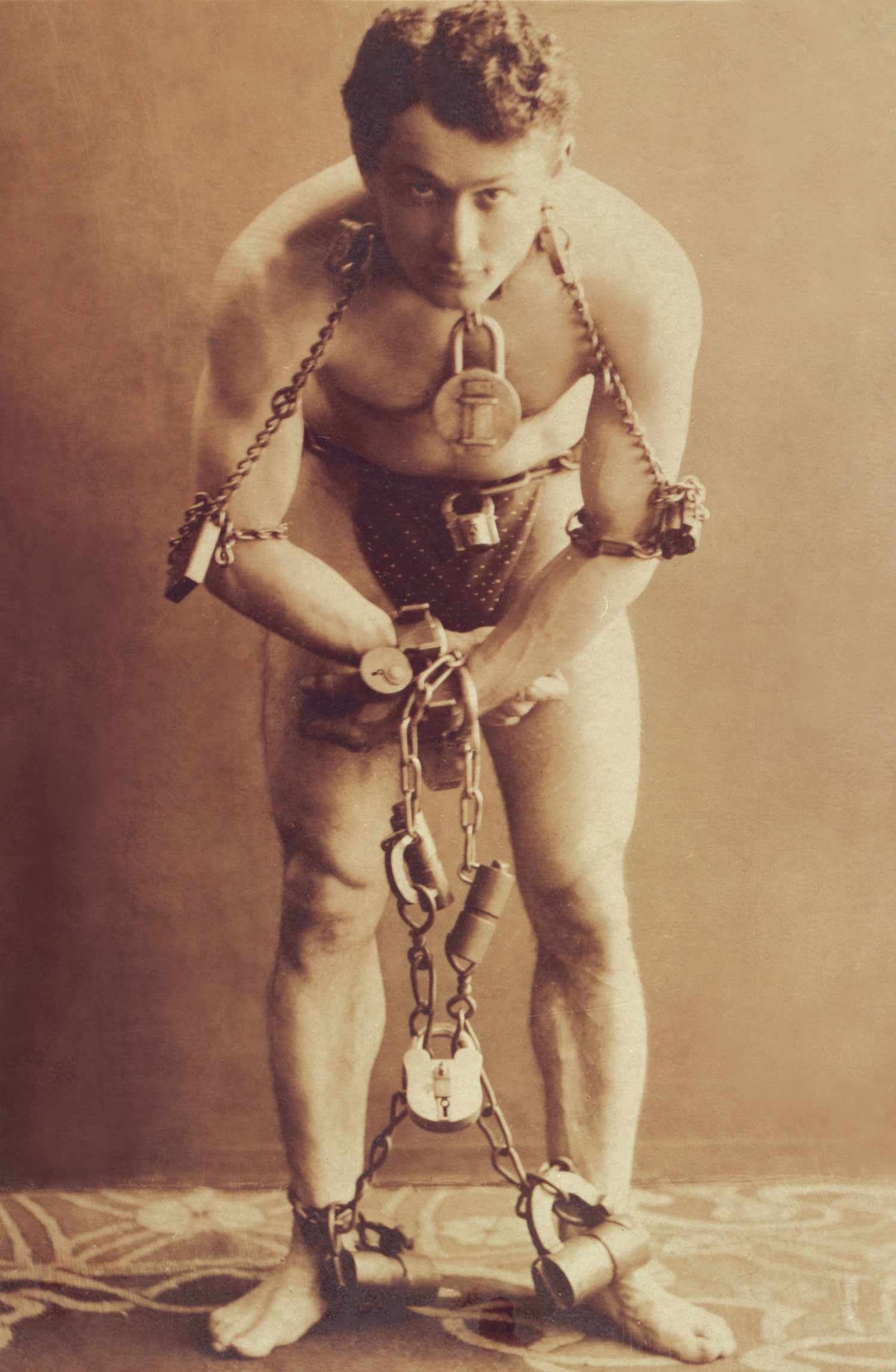

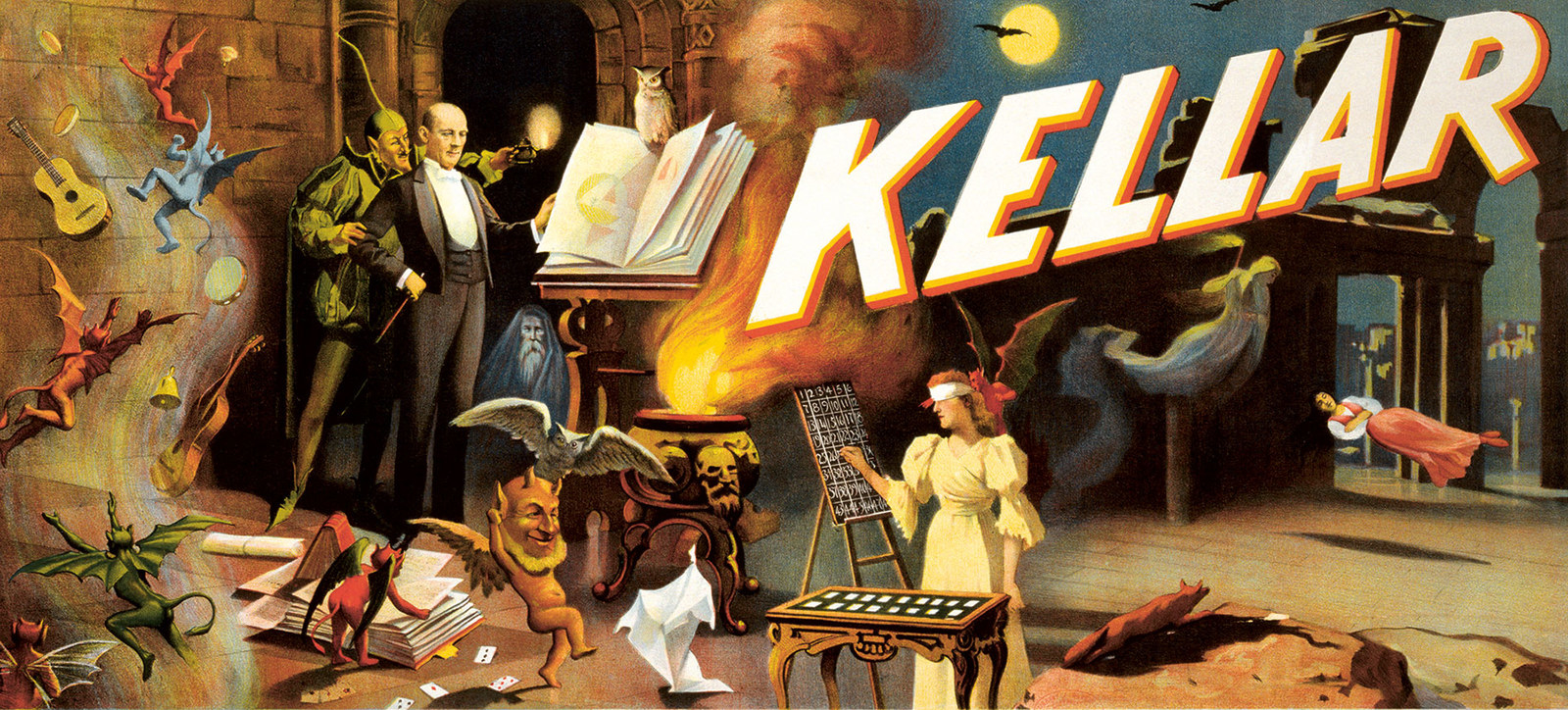

MT: Much of The Spectacle of Illusion is focused around turn of the 20th century. This time period is fascinating to me because of three key historical developments that were all happening in concert. One development was the rise of “modern magic” — the style of performance spearheaded by the French stage magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, from whom Houdini adapted his own stage name.

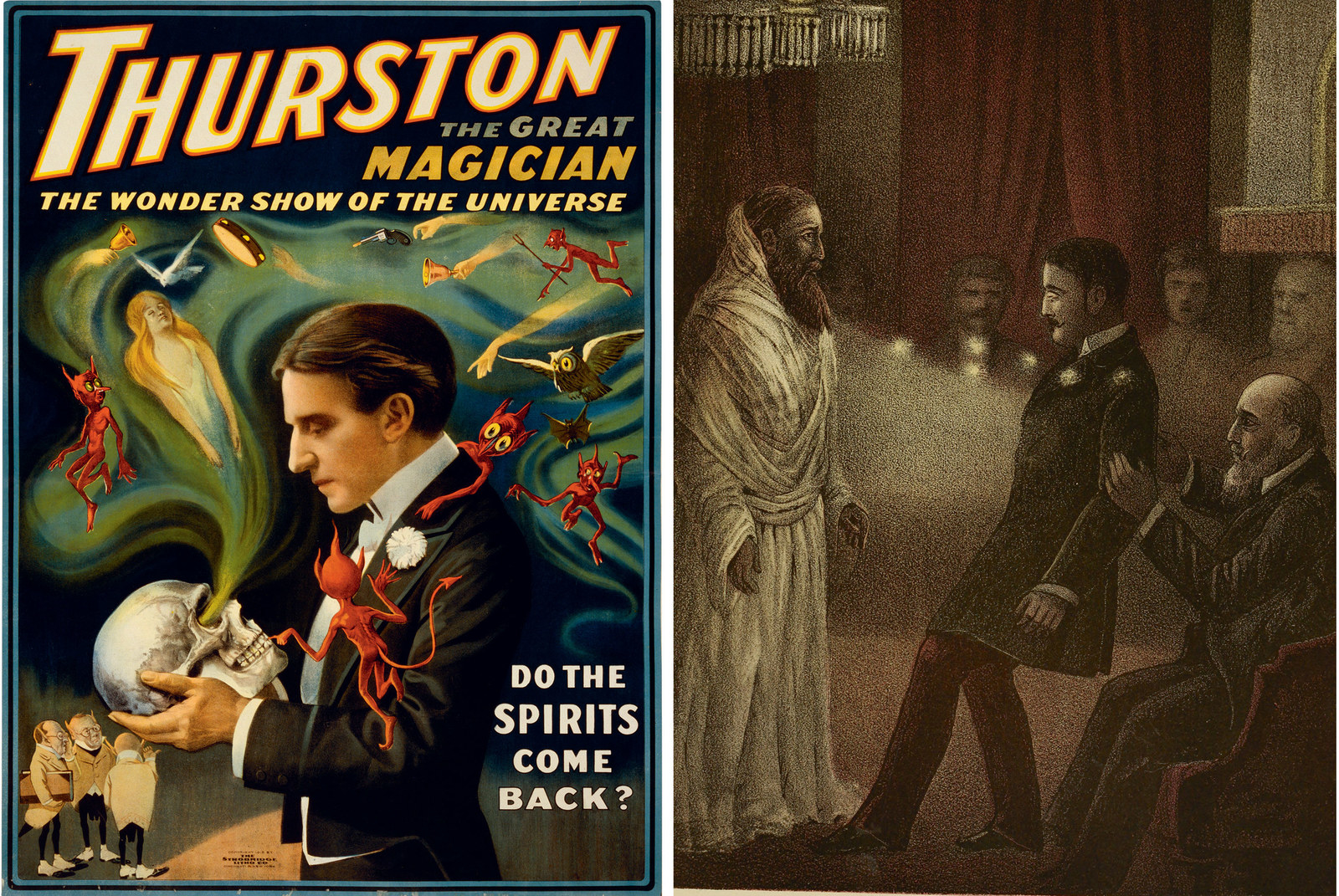

The second was the development of “modern spiritualism,” which was sold as a new kind of religion that offered empirical evidence of miraculous phenomena, where more traditional religions might have preached faith. And the third development was the emergence of experimental psychology as a scientific discipline, as researchers like William James and Wilhelm Wundt sought to legitimize the idea that the human mind itself could be the subject of empirical investigations — an idea that some of their colleagues thought was just as radical as the claim that mediums could talk to dead people.

The interplay between these three movements is really the driving narrative of the book. How fraudulent spiritualists would adapt magic-trick methods to in order to create illusions of empirical miracles. How magicians would use the act of debunking fraudulent spiritualists as a platform for promoting their own brands of entertainment. And how psychologists sought to develop methods to scientifically explore illusions and deception — variously embracing and confronting spiritual mediums, and sometimes appealing to magicians’ practical expertise to help drive their research.

Are any of these “illusions” still used today to deceive people?

MT: Absolutely. While magic methods and psychic cons have certainly developed over the years in many ways, there are definitely some core principles that seem to remain relatively dependable.

Hot reading techniques are a lovely example of this idea. Broadly speaking, cold and hot reading methods are used by performers to give the illusion of having access to knowledge or information that they couldn’t possibly have obtained by normal means. The performer might claim that information was obtained telepathically, or they might claim that the information was obtained by spirits whispering in ways only a psychically sensitive person like themselves can hear. The presentation is really only limited by the performer’s imagination.

These days, you can often learn a great deal of information about a person based on their publicly available social media. The effect remains the same, and the principle is similar, but Facebook updates can be used in place of informal networks of fraudulent mediums.

Can you talk a bit on how you went about uncovering these histories and researching this book?

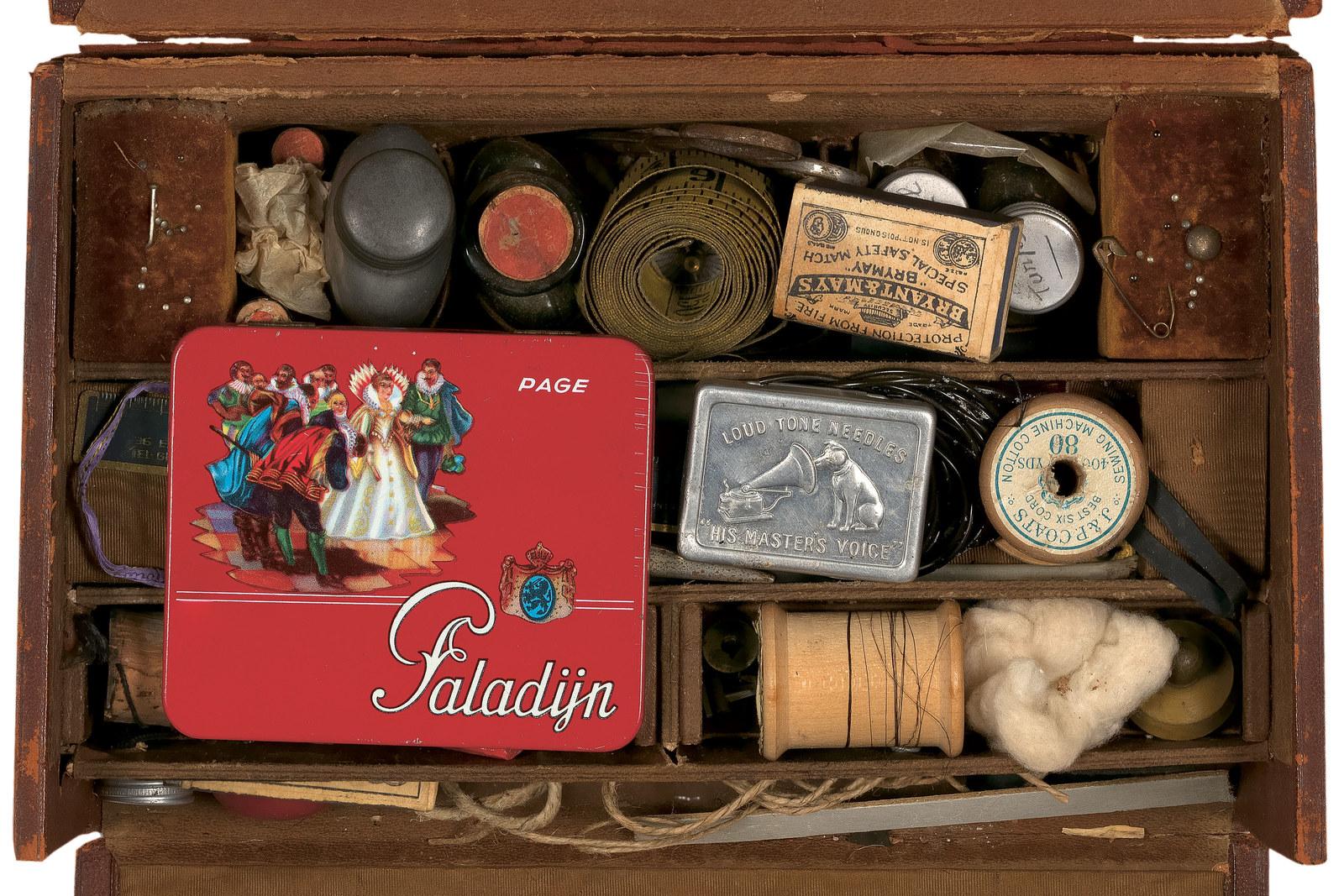

MT: Happily, I’d already been in the habit of collecting stories about magicians, psychics, and scientists when Thames & Hudson initially approached me to write the book. My research had begun when I first decided to conduct visual cognition experiments involving magic tricks as part of my doctoral project. In the process of preparing that project, I went searching for other examples of researchers who’d conducted similar work.

Unsurprisingly, it’s not a huge body of literature. In the present day, there’s been some great work by folks like professor Richard Wiseman and Dr. Gustav Kuhn, but I really dropped down a rabbit hole when I started looking further back. Turned out that a number of legendary figures in experimental psychology had been involved with magic and spiritualism, but it wasn’t the sort of work you’d find referenced in a contemporary textbook.

Has this book been a passion project for you?

MT: As an experimental psychologist and magician who incorporates magic methods into my experiments, I definitely feel a strong personal connection to this project.

Additionally, in the process of researching many of these events, I found myself developing a weird sort of affection for these characters. Even the ones who might, in hindsight, seem a bit...morally dubious. I love that I have the opportunity to make some of their stories better known again. Based on my own experiences and research, I’m quite skeptical of the claim that it’s possible to psychically or spiritually communicate with the dead, but I absolutely get the appeal of connecting with the past. I just prefer to connect via archives as opposed to mediums.

After your research was complete, was there any aspect of these histories that was entirely unexpected?

MT: I was initially quite taken aback by how intimately psychical research and early experimental psychology were intertwined. I can understand why psychologists were so keen to distance themselves from what they considered to be pseudoscientific ideas, but I think in some cases this has led to some really cool work fading into obscurity.

It was quite fun, as someone with a background in contemporary cognitive psychology, to wade into some of this early work. These were situations where the researchers were working in entirely new fields and developing novel methodological paradigms, often with mixed results. I was delighted to unearth little gems of work that ended up being remarkably prescient — forgotten studies of memory and unnoticed experiments on noticing.

What do you hope people will take away from this book?

MT: Psychology is an interesting science because people tend to believe that they are innately experts in their own cognitive processes. On a day-to-day basis, we all successfully navigate and interact with the world around us by using are perceptions and our memories. But in many ways, these processes do not operate in the way that we might intuitively feel they do.

As a psychologist who specializes in illusory experiences, I’m not trying to say that people’s minds are flawed or their cognitive systems are limited, but I am trying to say that these systems are often weirder than most of us imagine.