On the evening of April 25, 1986, routine testing at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant near Pripyat, Ukraine, went horribly awry as the worst-case scenario of our modern age was realized.

A catastrophic failure of the No. 4 nuclear reactor resulted in a massive explosion that released enormous quantities of radioactive fission products into the air. Within the first four months of the accident, 28 people had died and the surrounding wildlife populations were left devastated by the effects of radiation exposure. The nearby town of Pripyat was evacuated and has remained a virtual ghost town for the last 33 years.

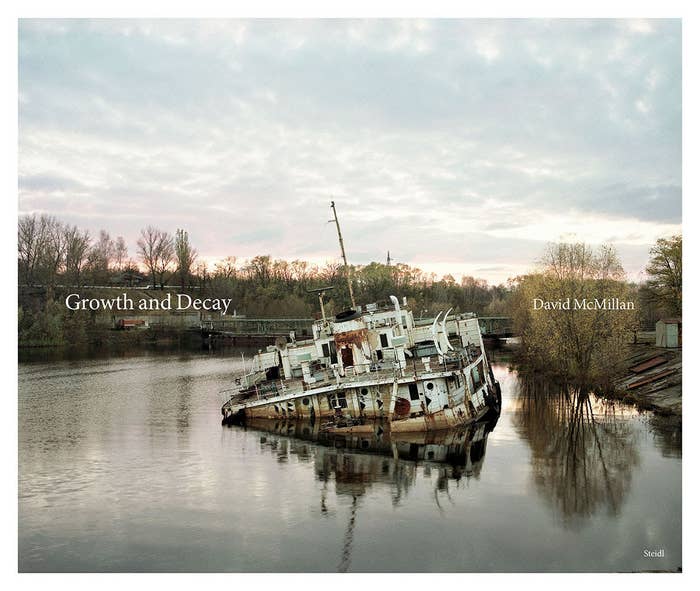

Since 1994, photographer David McMillan has made 21 trips into the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone — and under proper guidance and extreme care has documented the changing landscape as nature slowly reclaims what civilization is left in this nuclear wasteland.

His new book Growth and Decay is the result of these excursions and features some 200 of these haunting and beautiful pictures. Here, McMillan shares with BuzzFeed News a gallery of images from the book and his words on what goes into making a picture in a nuclear fallout zone.

What is it about Chernobyl that keeps you returning?

David McMillan: I studied painting, but became more interested in photography. The subject of my photographs had a lot to do with the tension between nature and culture and this led me to begin photographing in Chernobyl in 1994.

After that initial visit, I was happy with the photographs — and sensing I had only seen a portion of what was there, I returned six months later.

After several years of photographing in Chernobyl, it became clear that there was this dichotomy occurring: Nature was proliferating while the built environment was deteriorating, and this became the scope of the book.

Have you ever worried for your health or safety while making these pictures?

In the ’90s, I was often transported in vehicles too contaminated to leave the exclusion zone and I had to spend the night in a dormitory outside of the zone. These days, I stay in the town of Chernobyl and my guide drives his own car.

As far as safety is concerned, I accepted that there was a risk of sorts, but I was advised where the most highly contaminated areas were and to spend less time there. As the threat of radiation has diminished, the proliferation of wild boars has been somewhat concerning, but the current hazard is the buildings that are collapsing.

When looking back at years of work, were there new narratives or interesting details that you might have overlooked or not been aware of at the time?

My original visit in 1994 was speculative in the sense that I didn't know what I'd find or how freely I'd be allowed to travel. As I gained a sense of the scope of what was possible, I realized there were several themes I responded to, such as the abundance of Soviet-era artifacts and the aforementioned growth and decay.

The rephotographing of sites I had seen on previous visits became important, and photographs of floors and vegetation became new subjects for me. The zone was changing, and I wanted that to be part of the body of work. I have to say that on every visit, there were situations which I hadn't previously realized could make an interesting photograph, but suddenly seemed to have possibilities.

Is there a specific image or story behind an image that means a great deal to you?

With so many photographs made over a long period, there are several that seem key, in the sense they opened me to looking at a situation as having a rich photographic potential. Photographing the reactor from a fixed vantage point over the years, as well as Soviet flags in a stairwell, are examples that are intellectually satisfying.

There are some photographs I love for their unexpected beauty. An example is slippers and toys on a kindergarten floor that has extraordinary color. Some of the photographs have an emotional resonance because of the health consequences the accident had for so many people, and this has been most acute for me with the photographs of kindergartens and playgrounds.

Do you consider yourself an optimist in regard to environmental issues?

My optimism has been dampened lately by the stream of reports about arctic ice melting and governments unwilling to take the necessary steps to slow down climate change. Nor has the threat of a nuclear disaster lessened, from either weapons or accidents. I'm not a scientist, of course, so I can't give an educated answer as to whether it's too late, but I passionately hope it isn't.

What do you hope people will take away from your book?

I'd like to think that if this succeeds as art, then it's capable of generating complex emotions — including the apprehension of beauty coupled with the tragedy implicit in what is being described. I imagine some people will look at it because of a curiosity about the aftermath of the accident. Some will have their environmental views reinforced.

Do you plan on returning to Chernobyl?

Every year I’ve wondered if I should return, but I always concluded it was worth investing the time to find out. If I got a few new photographs it would have been worth it, and if not at least I tried. The book has seemed like a kind of summation, but I’d hate to not get that one next photograph that could be wonderful. There’s a good chance I’ll go again.