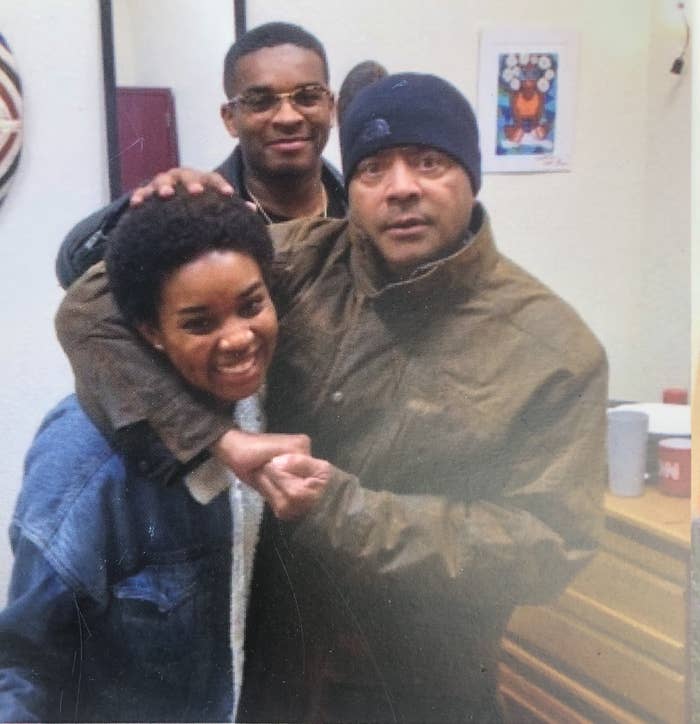

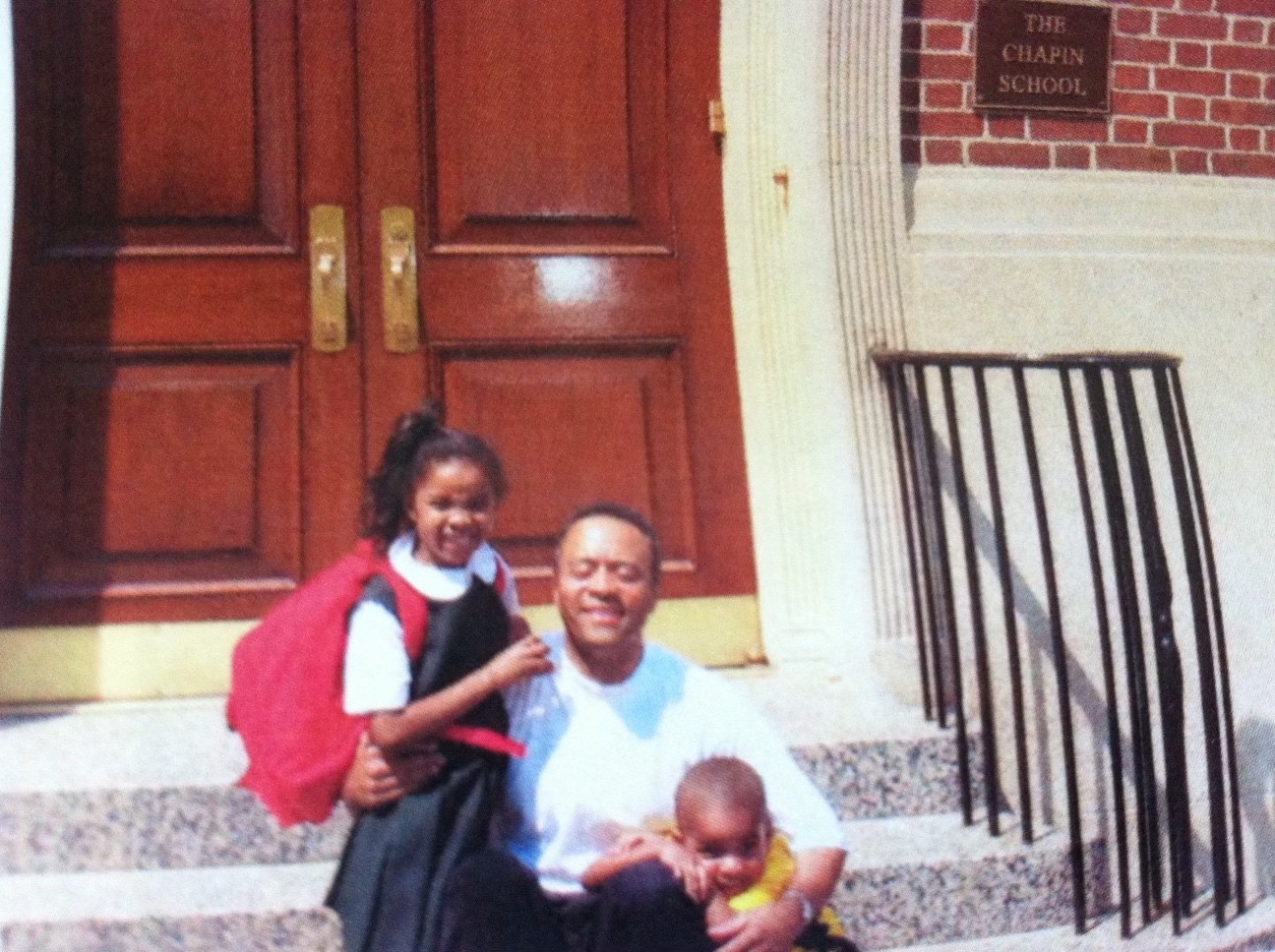

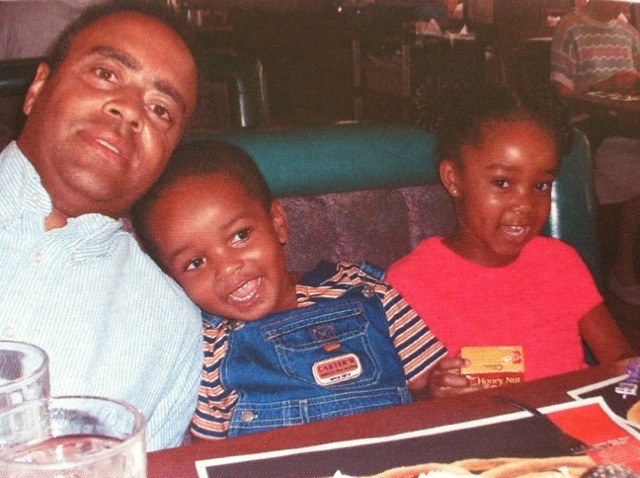

On June 13, 2020, my life changed forever. My father, brother, and I had driven to Hampton University, an HBCU in Hampton, Virginia, to retrieve my belongings from the dorm. It was clear by then that the COVID-19 pandemic was going to permanently disrupt my upcoming senior year. The entire drive, something just felt off with my father. I brushed it off as the exhaustion he likely felt while making the seven-hour drive to my school.

As I packed the remainder of my belongings, my father closed the door and asked my brother and me to sit down. The seriousness in his usually cheerful voice caused us to feel immediate concern. He then uttered the shocking words, “Yesterday, Tacoma police did a wellness check and discovered the body of Uncle Blakey. It was a suicide.”

I immediately burst into tears because I couldn’t imagine that my father’s brother, one of the people I trusted most in the world, was gone.

In the days following, I began to reflect not only on my uncle’s mental health but my own. As a 12-year-old, I had attempted suicide, but due to the stigma of mental illness in the Black community, I never talked about it; the only people who knew were my immediate family.

During that time, I felt ashamed that I was feeling depressed and that something wasn’t right with me. I had a stable home environment and family support, yet I still felt miserable. Instead of confiding in my family or even the therapist I had at the time, I continued to pretend that everything was perfectly fine.

Afterward, I struggled with emotions of guilt and shame because of one question that I was always asked: Why didn’t you ask for help?

It’s simple: I didn’t feel like I deserved it. As I saw it, there were more serious problems in the world besides a 12-year-old’s mental health struggles. While my parents had never directly said my mental health wasn’t important, I didn’t feel as if I could ask for help.

If it wasn’t for one of my classmates calling the police to do a wellness check, I truly don’t believe I would be here.

Once learning about my uncle, I wished I would’ve reached out more and talked to him about my own struggles. Maybe being open to sharing mine could’ve granted me more time with him.

The history of discrimination and racism in healthcare is a barrier to getting help

The Black community often shies away from conversations regarding mental health because of the stigma that is attached to mental health problems.

According to a 2013 study of 272 African American men and women ages 25 to 72 published in Nursing Research, about 30% reported having a mental illness, most often depression. In general, people were not very open to acknowledging psychological problems, were concerned about stigmas, and were more open to religious coping than other mental health services.

Mistrust in the medical field is a major reason why many don’t want to enter therapy, or even consider it as an option. Decades of racism and discrimination in the American health system, including mental health care, have been well documented.

“We have a lot of cultural mistrust in the medical and mental health professionals,” said Thomas Vance, PhD, an adjunct professor at the New School and therapist.

In the 1800s, psychologists such as Samuel Cartwright purposely created false mental health conditions such as drapetomania and dysaesthesia aethiopica, which characterized enslaved people’s efforts to escape as mental illness.

Used as a way to control the Black population, these harmful diagnoses weren’t disputed or addressed until decades later.

Given that the medical community has not historically been a safe place for the diagnosis and treatment of mental health problems for the Black community, many have considered religious or family support as safer and more acceptable than traditional psychiatric care. What’s more, a lack of health insurance or funds to pay for mental health care is a problem for many in Black communities.

People also don’t know how to reach out or get help, and, as a result, they continue to struggle in silence.

Growing up, I often heard dismissive responses like “you’re exaggerating” or “just pray on it” when expressing the need for a mental health break.

As a 12-year-old in a New York City public school, the day before I attempted suicide, I reached out to the school therapist. I was told she was too busy and that I should come back tomorrow.

Even though I was in therapy at the time, I didn’t completely feel comfortable sharing my emotions with my therapist. While she tried her best to be warm and welcoming, as a white person she couldn’t fully understand or empathize with many of the obstacles I was struggling with.

Black Americans face multiple challenges when it comes to mental health care

Finding a Black therapist can be incredibly challenging. Not only do you have to find one who takes your insurance or has a low copay but, the number of Black therapists is devastatingly low.

According to the American Psychological Association, African Americans only account for 4.24% of psychologists in the United States. (Psychologists make up roughly one-third of mental health professionals; therapists can also be substance abuse counselors, licensed professional clinical counselors, licensed clinical social workers, or marriage and family therapists.)

The Loveland Foundation aims to “bring opportunity and healing to communities of color,” particularly to Black women and girls, and has a therapy fund that helps defray costs. Other organizations such as Therapy for Black Girls and Black Men Heal are trying to bridge that gap and attract more Black people of all ages to try therapy.

“This started off with myself and several therapists volunteering our time and office spaces to ensure this program could happen,” said Zakia Williams, cofounder and chief operating officer of Black Men Heal.

Established in 2018, Black Men Heal was created as a resource to help more Black men on their mental health journey. Unfortunately, men are often pressured not to show emotions, not only in the Black community, but in American society in general.

“We tell our boys that showing emotion is a feminine thing. So, then they grow up and they don't show emotion,” Williams said. “When we are trying to get men to talk about their feelings and open up about being vulnerable, it's been embedded in them intergenerationally for so long that they immediately shut down.”

With rates of suicide in Black males ages 10 to 19 increasing by 60% in the past 20 years, Black Men Heal aims to decrease those numbers by destigmatizing therapy.

“Just like if you have a toothache, you go to the dentist — mental health should be seen in the same light,” Williams said.

Therapy for Black Girls is another organization that provides resources and help for people to get therapy.

“My core group is always going to be Black women because we are essentially the backbone of our community,” said Krystal Miller, social worker and owner of Melanated Mask.

Melanated Mask is a mental health center in New York that focuses on holistic mental health practices for BIPOC people. The center offers trauma-centered yoga, integrative mental health coaching, herbal solutions, and psychotherapy to help people on their mental health journeys.

Since 2018, Miller’s clinic has been advertised on Therapy for Black Girls with the goal of attracting Black people of all ages to experience the power of therapy.

“I kind of always knew that this is what I wanted to do,” Miller said. “I was doing a lot of peer counseling within my high school and within my Queens community.”

A large part of Miller’s work focuses on Black women, who are often seen as the glue holding communities together. While women are twice as likely to experience depression as men, Black women are only half as likely to seek care as white women.

“One thing that I've always asked whenever I did workshops for other Black and Brown women was: When's the last time that you saw your mother cry? Many can't answer that question,” Miller said. “Your mother is human. She has emotions. But she has to hold it together to get everybody else in line.”

Therapy may help you deal with systemic racism and generational trauma

Therapy may also help millions of Black Americans around the country who have experienced systemic racism that has seeped into numerous facets of our everyday lives.

“A lot of times we're encouraging folks to just go talk to somebody, but we forget that we have intergenerational trauma that got passed down,” Miller said.

When enslaved people were emotionally, physically, and sexually traumatized and then liberated without any psychological or economic restoration, this caused trauma that reverberates down through the generations, writes Dr. Joy DeGruy in her book Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome. “Due to being held captive, abused, raped and mutilated for the means of economic wealth, these formally enslaved peoples showed signs of what can best be described as PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder),” she writes.

During the Black Lives Matter protest of 2020, billions of Black people around the world were exposed to traumatic images of violence against Black bodies. Between May 25 and June 5, content relating to Black Lives Matter was viewed on social media over 1.4 billion times. The extreme coverage and often uncensored videos and images have retraumatized generations of people in the Black community.

“While some people felt good about finally having these conversations on an international scale, some were drastically impacted with negative effects on their mental health,” Vance said. “This is where terminology such as ‘racial trauma’ pops up and we start learning that type of language. It's not just traumatizing; this is racial trauma, which is uniquely different for Black, Indigenous, and other folks of color, because it impacts them specifically.”

Destigmatizing language is one of the easiest ways to make therapy appealing. Pushing back against phrases such as “he/she is crazy” or “therapy isn’t for Black people” can help break that social stigma associated with therapy and make it appear less scary to some.

“We need to keep the media accountable when they're utilizing language that is stigmatizing,” Vance said. “We need more mental health professionals entering those spaces and having those conversations.”

When I was in therapy as a 12-year-old, I didn’t feel fully comfortable expressing all of my emotions. Now as a 23-year-old with a therapist who not only looks like me but can relate to my experiences, I can say: It really does work wonders.

“You have to be comfortable with your therapist,” Williams said. “That's why Black Men Heal has been such a success.”

Black people are not a monolith and occupy a variety of spaces. Black Men Heal takes a deeper look and doesn’t just pair people based on race but takes into account one's environment, gender identity, and a plethora of other factors.

It’s also perfectly normal if you and your first therapist aren’t the perfect fit. It might take two or three to find someone you feel comfortable with.

“If you feel like you are not comfortable with one therapist, it's OK to start over until you find that right fit,” Williams said.

Breaking down the social stigmas when it comes to therapy isn’t easy, but taking those first steps into exploring what it can do for you can make all the difference. Therapy is a necessity that all Black people, regardless of financial status, should have access to. While it is often perceived as a scary and shameful thing, it is the complete opposite. No matter the stage in your life, you’re going to encounter problems. Having an unbiased person listen and help you solve those issues can truly make all the difference.

“For us, especially as Black women, we are the holders of our seven generations before us and seven generations after,” Williams said. “So, what are we doing differently for those who are coming after us?”

As I reflect on that dorm room conversation I had two years ago, I believe it was a wake-up call. I had attempted to neglect my mental health and distance myself from therapy, but my uncle’s passing forced me to reexamine it.

Seeking help and speaking out for the first time can be nerve-racking but if it’ll save your life or the life of a loved one, I promise you it’s completely worth it.

Dial 988 in the US to reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. The Trevor Project, which provides help and suicide-prevention resources for LGBTQ youth, is 1-866-488-7386. Find other international suicide helplines at Befrienders Worldwide (befrienders.org). ●