The campus of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff was empty, blank, and cold — like much of the landscape my father and I had driven through on the way from Little Rock. I was back at home for Christmas this past year, now a full-grown 32 years old. Though we only lived 45 minutes away, and though I’d attended a historically black university myself, I’d never actually walked the campus of my dad’s alma mater, the place he talked about constantly. He remained stubbornly convinced it was the best university in the world.

He’d grown older since the last time we’d driven together, and so I felt guilty for riding shotgun. But having spent his adult life driving from one rural town to another, working to help community organizations throughout the Delta get grant money, he knew these country roads like the wrinkles on the backs of his hands. Having moved away to Washington, DC, at 17 to attend Howard University, and then on to New York City, I barely drove.

Once on campus, I snickered at everything I could: the odor that permeates the town of Pine Bluff, until you grow used to it (sulfur from a nearby paper mill), the haughty pride residents harbor for their native city. I made jokes at the expense of the place, took the kind of mincing steps that are the physical equivalent of pinching your nose around pools of stagnant water.

The jokes were meant to cover my nerves. I could feel us inching toward a fight I’d thought we’d settled in the intervening years. But, to be honest, my dad was starting to annoy me — how quiet he’d grown, how reverent, nostalgic, while marking what had been where, back in his day. Past the old agriculture fields, which had provided useful information to black farmers intent on maintaining their families’ land. Past the building that had once housed the laundry where he’d made money to pay his tuition. I knew that eventually I was going to say something that would set us off, take us right back to the arguments we’d had more than a decade and a half ago, as I’d agonized over my college decision.

We’d worked ourselves into such a froth of passive aggressiveness that one night in the spring of my senior year of high school. I splayed the acceptance letters I’d received from the four colleges I’d applied to across the dining room table, my attitude that of a spades player holding the last four books. This was me setting him. I asked him to pick for me, complained that I just couldn’t decide. He bested me by taking the folders with Ivy League crests on them, the ones he knew I coveted most, and casually tossing them to the floor.

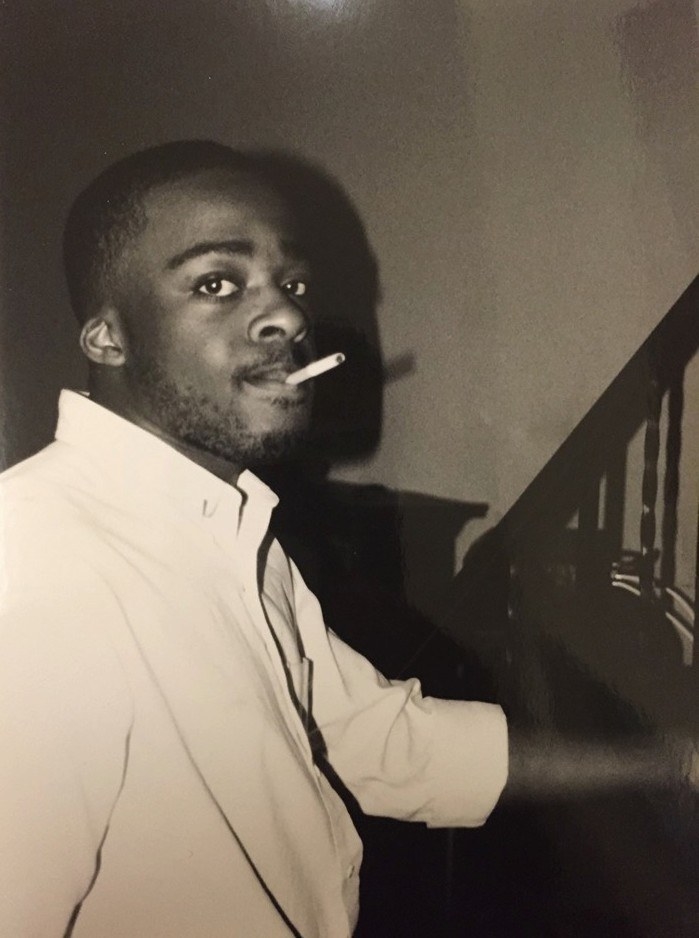

My father grew up as one of 13 children on a farm in the Union Chapel community in central Arkansas. Once he’d graduated from his local segregated high school in the mid-1950s, he — like any other black person interested in a college education back then — had attended a historically black one: the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, known at the time as the Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College. He managed to stay for two years, joined the military to secure more funding for school, and then returned to finish.

Most black families, like mine, are only one or two generations removed from segregated schools being the law of the land.

The University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, the state school established under the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 in an effort by the federal government “to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes,” was not an option for him, or for many other promising black students in Arkansas who were denied access to state universities by Jim Crow laws that prohibited integrated public education.

My father remembers that history of disenfranchisement quite lucidly, as do the other alumni of AM&N. They were beneficiaries of a second Land Grant Act, the Morrill Act of 1890, which established many of the HBCUs that educated black populations throughout former Confederate states. Many black scholars arrived on those campuses from farms, much like my father had, and from there lapped the globe.

Much of this country does not, it seems, remember that history — or remember who got loans to buy houses, or who got to use water fountains, or whose granddaddy came home from the war and got a voucher and whose didn't. But the truth is that most black families, like mine, are only one or two generations removed from segregated schools being the law of the land in our country. The legacy of that history hasn't disappeared, just as — despite America's best efforts — neither have we.

To my dad, with his history, my hesitation in choosing a school must have seemed fatuous and entitled. For me, it wasn't so simple. I had already dismissed land-grant HBCUs like the one he'd attended (schools with "state" in the name) in favor of private ones — Morehouse and Howard — that to me were glamorous by association with shows like A Different World or Living Single. Those were the schools my older cousins had chosen, whose parents had made it out of the countryside by now and into the suburbs. Those were schools, I thought, where you could walk around haughtily because you’d been granted access to a secret dialogue — schools you could brag about at the family reunion.

I worked myself into a frenzy, breathless over what a bold stroke it would be for me to choose an HBCU. I convinced myself that it would be a salve for my own feelings of disenfranchisement, that it would be a place where I could exist outside the myth America had written me out of — that there I would not be exotic or exceptional; I would be real, in a way I had never felt up until that point.

In the end, I decided that place was Howard. Or rather my dad and I decided, since they offered journalism as a major, and I’d expressed a desire to be a writer. I picked up the other folders from the floor, signed the cards to say that I would not be attending, and so seemed to have signed away whatever purchase I’d established within the American meritocracy. Doing it felt powerful and romantic — pushing away the Great American drives of capitalism, individualism, and egotism.

Howard snatched that romance from me quick. I brought books and dreadlocks down to my shoulder, tortoiseshell glasses, patience for conversations deep into night, and a dream of being a writer. But there were other dreams that showed up, and I always felt as if I were playing runner-up to the School of Business kids who flooded the yard in their suits, and the bio majors who eschewed talk for textbooks. I envied many of them their first internships, which seemed impossibly fancy, and the institutional support I saw them getting. I cracked wise about how folks only got excited over niggas doing STEM, made what I thought were clever associations between the University’s favoring practical sciences over my beloved humanities with Booker T. Washington raising us from the plantation.

I shrank into myself, first from the same shock we all encountered — that we were not the only smart black students in the country — and then from what lingered: that journalism was not the same as fiction writing, that the school offered a total of two creative writing courses in prose writing, and that by the end of my freshman year, I’d completed them both. The stoicism with which my father met my requests to transfer over the phone, telling me to stick it out, made me feel for the first time the limit of my privilege. With two siblings also pursuing advanced degrees, saying no to a full scholarship was beyond our family’s means. Having very little experience then with money myself, I instead took this to mean that my father’s pride was worth more to him than my well-being.

I decided that it wasn’t about the money, but rather a score he wanted to settle to prove that HBCUs were just as vital as any other university, and that made me bitter toward the school — but more pointedly, toward him. I suspected that he heard my laments about the lack of support for humanities at Howard as a façade, me still needing to hold myself apart from the place somehow. To my father, HBCUs provided everything there was to want in all the world.

To my father, HBCUs provided everything there was to want in all the world.

I guess I'm a part of that retention story you hear, about HBCUs struggling to support students through graduation — though a bit of an exception maybe, as a kid who arrived on full scholarship and four years later walked away without a degree. By then I’d skipped way too many classes to matriculate in four year, holed up in the library reading, writing, desperate to keep my dream of writing novels alive. Pride kept me from asking for help from anyone at the university, and pride drove me away. I was too ashamed of sticking around longer than four years to get a degree I fantasized about not showing up to receive, anyway.

For years after I left Howard, I struggled with a creeping insecurity that my entire academic career had been a waste of work. In my mind, every résumé or round of pitches I never got a response to, which in 2008 was a brutal number of them, had less to do with a struggling economy and more to do with the fact that I hadn't gone to a school with strong enough inroads into New York media. I had put myself in a position where I'd had to be twice as good, and had failed to do it. I didn't know enough about media, or the way that it was changing then, to blame the industry itself — and so I blamed my father, instead.

That’s what was getting to me this past winter, and what pricks at me whenever he takes on a tone of braggadocio. It sounds so flimsy to me now, that tone, even 15 years beyond the first time we ever talked about colleges. It sounds so much like the weak pride I summoned myself those first years at Howard, what I'd taken up but had not fully believed. It sounds like his need to stoke his own pride, a need I can acknowledge and respect, but it also feels like a denial of my experience, a refusal to acknowledge that such an experience almost broke me.

In the car on the way to Pine Bluff, I found myself facing the fear, again, that my father knows something I don’t. It’s so difficult to see history through his eyes, even when that history comes from his own mouth. I fear that not knowing it will require him, again, to rescue me. I’m older now. I’m supposed to be doing the rescuing.

I think my dad tried to teach me to distrust the need I felt to distinguish myself with false laurels, and certainly not to pursue those laurels without thinking about how they might serve the wider black community. America had made him wary of words like “Ivy League,” and wary of traditions he thought devalued people who looked like me, pinned a ribbon to some and shushed others.

But I fear that when I most need to remember the lessons he tried to impart, I will have forgotten them, or find that they are not my own. Maybe that’s the reason we talk to one another the way that we still do: him desperate to make sure that I know what he wants me to know before he can’t tell me anymore, me desperate to show him I can take care of myself. Maybe the truest thing he wanted me to know is the unending tension of Du Bois's double consciousness, the legacy of systematic oppression — that the tension won’t leave you in the face of your tantrum, that you will constantly work to resolve it, that you cannot wish yourself into someone else’s myth. That would be suicide.

You cannot wish yourself into someone else’s myth. That would be suicide.

I’ve watched students graduate from HBCUs, both Land Grant and private schools, and wondered what was wrong with me that I did not find the experience as rewarding. Lack of patience, maybe, the need to be living a narrative that seemed coherent — an instinct that made me inflexible, something that life would teach me anyway.

At times, I’ve been critical of HBCU old-heads like my dad — that they have to be so dogged in their institutional loyalty, so unyielding about what such institutions meant to their lives, and what those schools will mean to yours. I also know the history those institutions come from and resent that they have to argue for their continued legitimacy. My vision was not long enough when I was at Howard, to understand how the university was working to sustain itself, or to understand that I, for the privilege of attending that school without accruing any debt, had to begin to understand myself as a part of that larger ecosystem. I certainly did not commit myself to making the institution into a place I could speak of as reverently as my father does of his alma mater.

This week, I shut my computer after reading that Betsy DeVos had visited Howard’s campus to meet with the current president, Wayne A.I. Frederick. I shrank from the photo of all those university presidents pinched into the Oval Office like a preacher’s collar. I laughed heartily along with my father, which was nice, when they complained that President Trump had hoodwinked them into little more than a photo op, agreeing that yup, they should have known better. Because, in many ways, I still act like the University is mine.

But hearing Betsy DeVos call HBCUs “pioneers when it comes to school choice” incensed me; it made me slap my hand over my mouth. She’d shamed me by snatching language I might have applied to my own predicament a decade ago. I’d wanted choice, then.

Ultimately, I had to choose New York to find my tribe: black people who read and talked with the same abandon that I did, some who are HBCU alums, some expatriates like myself, some who never went at all. I love HBCU alum sweatshirts, what they mean to say to the world, acknowledging the secret those students speak to one another and the marvels they’ve seen. But I won’t wear one. I’m only an alum the way Puffy is one — wise enough to speak of validation stickers and Soul Food Thursdays in the Blackburn, but only just.

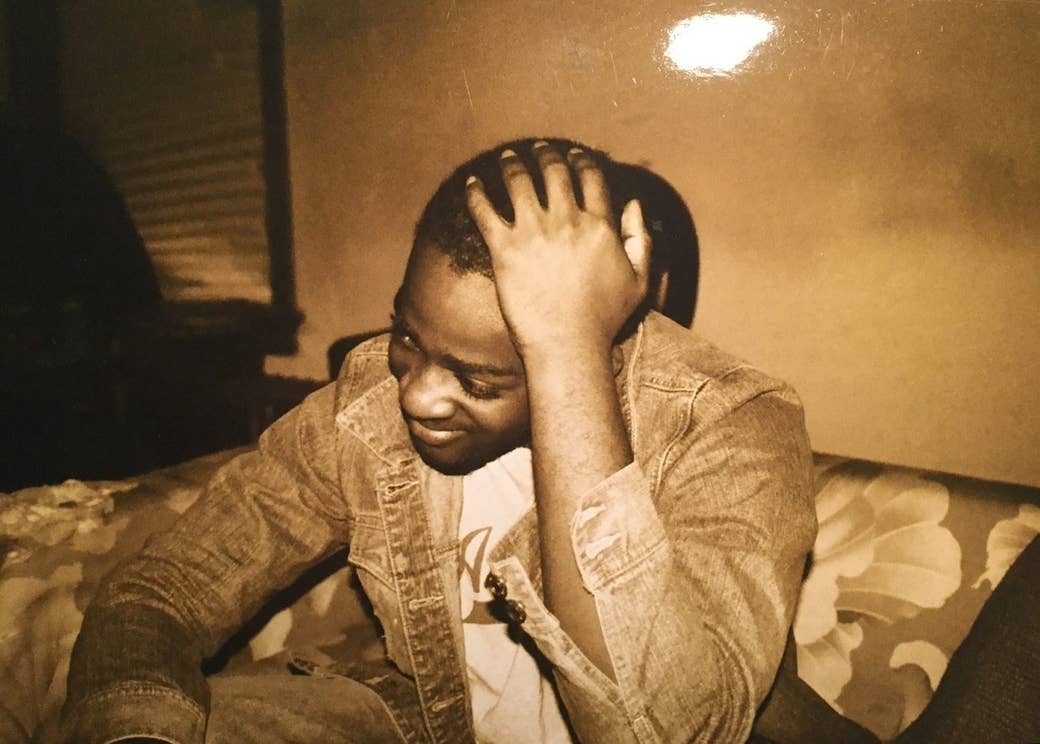

Many called for Betsy DeVos to consult the histories of historically black institutions, following her gross misinterpretation of what they represent. I’d like to submit these two histories, my dad’s and my own, to be considered as well. Because that is a history: me as a high school senior trying to make a college decision, me standing in the bleachers for Black College Football Classics, me in the years since I walked away from Howard. My own life is a reckoning with the history of HBCUs, and with the families and communities these schools have shaped.

HBCUs and their legacy have been a burden I’ve wanted to slough off at times, for the things I thought they cost me. It’s tempting to want to ignore their history, to wrap them in language that makes them more convenient to our contemporary moment. But that’s not the way history works.