Depending on who you speak to, Colleen Hoover’s novels are the be-all, end-all of horny contemporary literature or the end of culture as we know it. Her work has become a lightning rod on #BookTok, where her superfans, called the CoHort (cute), react to her work’s steamy sex scenes and narrative twists. But haters often point out that a number of the central relationships in Hoover’s novels feature semi-fucked-up power dynamics at best and romanticized abuse at worst. Not since E.L. James’s Fifty Shades saga has there been an author’s work as simultaneously beloved and derogated as Hoover’s.

According to the New York Times, Hoover’s books have outsold John Grisham’s and James Patterson’s combined. The woman behind them is just as much of a phenomenon as her work. Hoover, a self-made author, navigated the cutthroat, tricky publishing world on her lonesome. Her first novel, 2012’s Slammed, was a young adult romance book, more adult than young, about a high school senior navigating a romance with her English teacher. (Many of Hoover’s novels focus on women — young or otherwise — in semi-forbidden relationships with men.) It was self-published and, though it took seven months, eventually reached #8 on the New York Times’s paperback fiction bestseller list; 10 more of her books have reached the list since.

Within a few months of Slammed’s publication, she had earned $50,000 in royalties. Even after Atria, a branch of Simon & Schuster, published a few of her books, Hoover opted to self-publish another, 2013’s young adult novel This Girl (the third book in the Slammed saga). She does not need anyone — a business, a publisher — to advocate for her writing; she has done it all on her own terms.

Amidst the headlines and TikToks, a conversation about the nature of Hoover’s work has been lost. Concerned tweets don’t often go further than identifying her stories’ troublesome relationship dynamics or lazily labeling one of her books “the worst piece of English literature.” I read approximately 4.8 of Hoover’s novels, about 20% of her oeuvre. It is certainly easy to slot Hoover’s work into the supposedly lesser subcategory of fiction known as “women’s fiction,” if only because Hoover’s work centers on female characters. But her work spans several genres: She writes young adult novels, thrillers, mysteries, and straight-up romances. The women at the center of Hoover’s books are laser-focused on their immediate worlds: who they love and why. That’s often a man, but can, at times, extend to family (as is the case with Slammed’s dying parent subplot).

Her women are detached from the news, detached from politics, mostly detached from friends and their jobs, in a passive and uninteresting sort of way. The protagonist of Ugly Love, a young nursing student named Tate who falls in love with her brother’s moody coworker Miles, is rarely ever at or interested in her school or work. She does nothing but hang around her brother’s apartment. “It’s been two weeks since I’ve seen Miles but only two seconds since the last time I’ve thought about him,” Tate tells us, information I would never want to hear from a nurse. If there are people she’s seeing apart from colleagues and these two men, we’re granted no access to them. Her life begins and ends within the apartment building where her crush lives.

Hoover’s women are often orphans, or living far from home, tethered only by their relationships to Hoover’s men, who are at best aloof and evasive, and at worst, downright manipulative — like Jeremy, who lures self-professed introvert Lowen to his Vermont property under false pretenses in Hoover’s 2018 Rebecca knockoff, Verity. The fantasy that Hoover often presents in her writing is one of sexy domination, not unlike E.L. James (who is thanked in Hoover’s acknowledgments). Smart, supposedly competent women allow their worlds to be turned upside-down and inside-out by dynamic, intriguing men they meet because for the first time in their lives, they’re being seduced.

In Slammed, 18-year-old high school senior Layken (her parents couldn’t decide between “Layla” or “Kennedy,” so Layken it is) relocates from Texas to Michigan and falls for the cute neighbor, a slightly older boy named Will who takes her to a poetry slam before the two make out ferociously. But when she shows up at her new high school, it turns out that he’s her English teacher, setting the novel on a whole other course. It’d be one thing if the two were able to keep their hands off each other, or if they lived more than a house apart, or if their younger brothers weren’t best friends, but Hoover’s circumstances dictate that Layken and Will are thrust together again and again until they can’t resist. “Nothing about this has been easy,” Will tells Layken. “It’s a daily struggle for me to come to work, knowing this very job is what’s keeping us apart.” The agony!

For Hoover’s women, it is better to have nothing with someone than it is to have no one at all.

These are quite conservative novels, all things considered, by which I do not mean “Republican” or “neo-fascist,” but traditional and retrograde. For Hoover’s women, it is better to have nothing with someone than it is to have no one at all. In Slammed, Layken’s love interest being her English teacher is treated as a romantic obstacle or administrative inconvenience, not an abuse of power or even a controversy (the book bends over backwards to remind you that she’s 18, which makes it fine). The obstacles Hoover comes up with are not supposed to actually make these relationships unappealing — just the Big Bad to be dispelled before true love can prevail. So what if Lowen’s love interest Jeremy is keeping his first wife alive in a coma! So maybe Tate’s crush Miles is still mourning his first love, who happens to be his stepsister! The expectation Hoover sets in her work is that love can overcome all — even if it ends badly, even if it seems wrong. The endings, in turn, get repetitive: No matter the problem, how scandalous or tormented the person or situation, these two end up together, bound for life.

It’s possible that Hoover’s books are popular merely because, like those of James and many novelists before her, they are rich with graphic sex scenes. There’s a significant range on display, from the relatively conventional sex scenes of Tate and Miles doin’ it missionary style (“‘I want you on your back,’ he whispers”) to the more evocative depictions in Verity, in which Lowen becomes obsessed with the toothmarks on Jeremy’s headboard, a symbol of his first wife’s pleasure. “Sometimes, I would straddle my pillow and bite down on the headboard while I touched myself, pretending he was beneath me,” she muses. Later on, she gets to live her fantasy: “I can feel Verity’s teeth marks beneath mine... I bite harder into the wood as I come, determined to leave deeper marks than she ever did.” Hot? I’m not sure. But funny, definitely; evocative and memorable.

On a craft level, Hoover often exemplifies a trend in postmodern language degradation with sentences that are plain, expected, and rhythmically repetitive. She is reliant on adverb and adjective-rich descriptions. Eyes are not brown, but chestnut. People walk not slowly, but languidly. Her narrators believe themselves to be the center of the universe — often a side effect of seduction. In many ways, this puts her work in conversation with Harlequin romance novelists before her, who seek to create a particular type of easily absorbed image (fluttering eyelids, a strong hand on a breast). Hoover favors the present-tense first person; sometimes the books have the narrative gumption to switch points of view each chapter. It’s stream of consciousness without the actual consciousness. Mostly the prose reads something like a nature documentary script: Here you see the woman debase herself, here you see the woman forgive the man. “I just smile gently at him. He doesn’t return the smile, but he doesn’t look away. We hold eye contact for several seconds, and I feel his stare stirring things up inside me,” Lowen reports in Verity.

After a significant time dedicated to the Hoover backlist, I found myself charmed, even somewhat hooked. They are quick reads, full of heavy petting and light introspection. They are entertaining. Having picked one up, I willingly picked up more. At their best, Hoover’s books are begging for a streaming service adaptation; I just know that at least a couple would make for great Hulu originals (derogatory), with their lusty, lurid suggestiveness. Imagine — this could be happening in a simple little town like yours.

They are quick reads, full of heavy petting and light introspection.

But if it wasn’t the writing, and the endings grew more and more predictable, what was it that kept me — and many other readers — crawling back? For that answer, I went not further into Hoover’s work but to the recent tabloid magnet Don’t Worry Darling, director Olivia Wilde’s sophomore film. In Don’t Worry Darling, a young couple, played by Florence Pugh and Harry Styles, live in a sleek, 1950s-inspired utopia where the men work all day and the women clean and gossip and fix cocktails. There’s something amiss in their little suburb, though it takes the length of the film for Pugh’s character to realize what that is. The film’s politics are muddled at best, but perhaps what’s most intriguing (and messy) about Don’t Worry Darling is that it doesn’t seem to find the 1950s inherently bad. It embraces midcentury modern aesthetics with a shrug; hey, it’s easy to look good in an A-line skirt. No matter the blatant oppression endured by women, queer people, and people of color during that era. That Don’t Worry Darling’s characters are content — to a point — feels not unlike Hoover’s hetero heroines. Her books share that kind of traditional belief that these old-world gender dynamics are totally fine, as is deferring to a boyfriend or husband at every step, as long as they’re chosen.

Hoover’s novels are about women to whom things happen, not who make things happen for themselves. These men enter their lives via serendipitous happenstance. Anything bad that could happen to a woman, to anyone, does. Cancer, heart attacks, death of children, death of parents, abuse, gun violence — it’s all there. The world is terrible for women; we know this. Perhaps there’s a degree of catharsis for some of the readers of Hoover’s work: The world is bad, even for women who are always cumming (also the plot of Don’t Worry Darling, more or less).

One series in Hoover’s bibliography attempts to break the form, starting with 2016’s It Ends With Us, about a young woman named Lily whose tormented relationship with hot neurosurgeon Ryle — Ryle — recalls her father’s abuse of her mother. Regardless of the book’s mechanics, and Ryle’s pleading, Lily winds up forging her own path ahead (hence the title). Though the book is dense with relatively troublesome aspects — an unwanted pregnancy is kept, for instance — the typical narrative is questioned. This time, no matter how screamingly good the orgasms are, the relationship itself is deemed not worth it.

In the book’s acknowledgements, Hoover details the book’s similarities to her own upbringing, saying the abusive relationship in the novel is drawn from her own parents’ story. In the thoughtful and elegant author’s note, Hoover writes, “At times, I wanted to hit the Delete button and take back the way Ryle had treated Lily. I wanted to rewrite the scenes where she forgave him and I wanted to replace those scenes with a more resilient woman — a character who made all the right decisions at all the right times. But those weren’t the characters I was writing. That wasn’t the story I was telling.” Her books are not meant to be instructive: She is showing us what she knows.

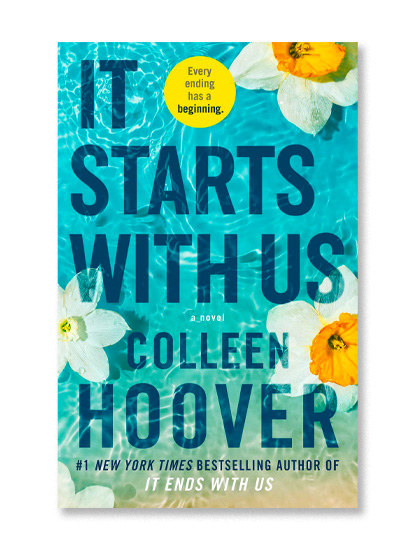

Hoover’s latest novel, which came out last week, is a combination prequel and sequel to It Ends With Us, called (what else?) It Starts With Us. This book sees Lily pursue romance with lost love Atlas amidst the ashes of her old relationship with Ryle. The expansion of the It Ends With Us universe might provide some closure for Hoover’s readers, who, Hoover’s preface notes, rushed to TikTok to ask what would happen with Lily and Atlas.

Yet Hoover’s decision to return to one of her more prescient and realistic(ish) texts suggests that she’s still pushing the idea that love conquers all, that the way out of abuse is through another man, another lover. Hoover’s women are rarely, if ever, thinking outside of their romantic relationships, or lack thereof. If they’re not thinking of men, they’re thinking of the women who surround their men — their ex-wives, ex-girlfriends, ex-stepsisters-turned-girlfriends — or maybe their parents, and their own suffering. They are, for better and worse, daughters of fathers or girlfriends of boyfriends, women who cannot exist by themselves, because neither they nor Hoover know what they would be — or if they even matter. Maybe they don’t want to be out there, though. “There’s nothing in the world that compares to the feel and smell of brand-new rain,” Tate says in Ugly Love. “His lips come down gently over mine, and I find myself comparing the feel and smell of brand-new rain to his kiss. His kiss is much, much better.” ●