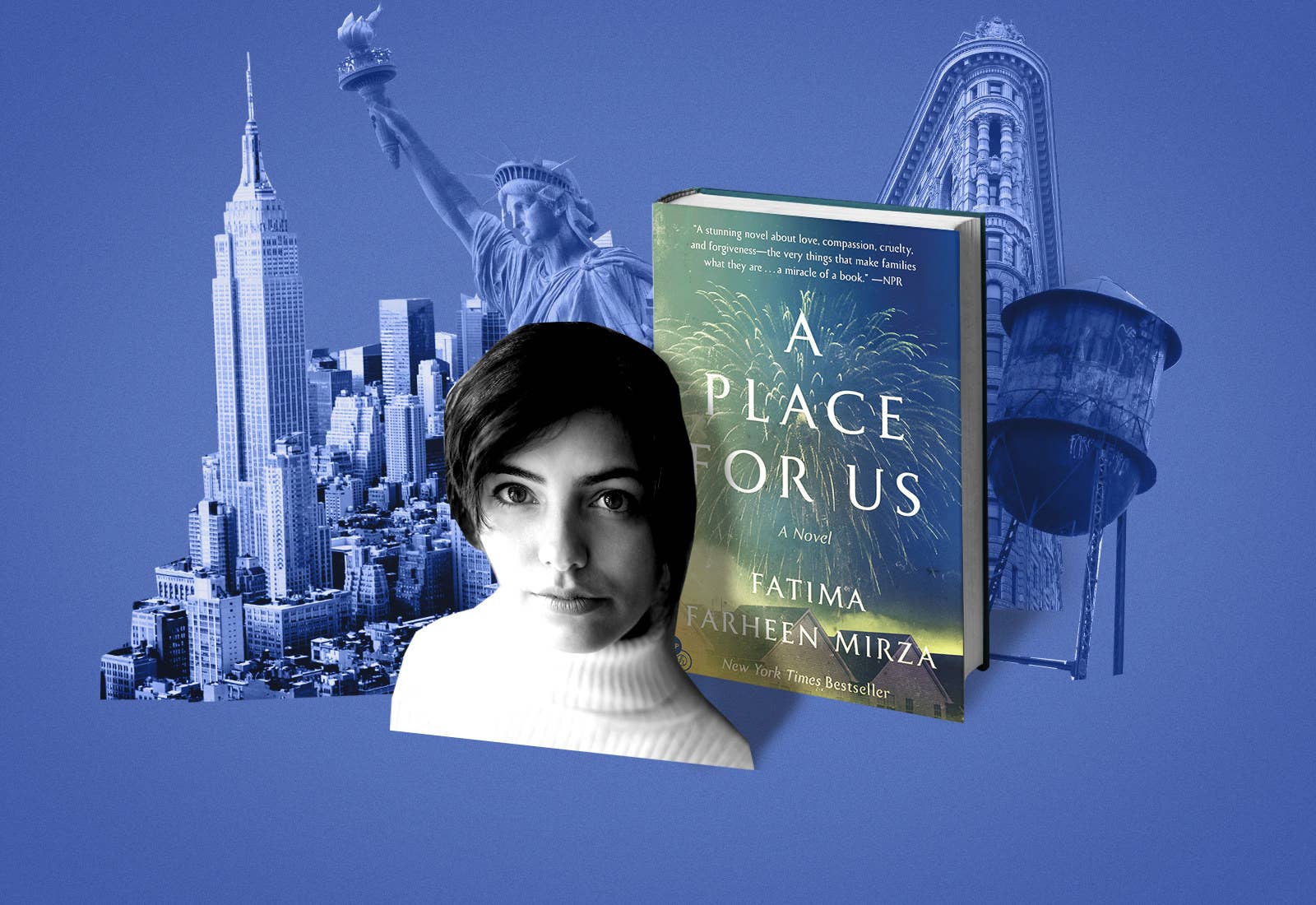

A Place For Us is one of five books selected for this year's One Book, One New York program. You can get more information and check out the other books here.

Hadia is thirteen and sitting on the top of a picnic table painted red, loosening the knot of her scarf and watching the boys from her Sunday school class play basketball during their lunch break. Amar is among them, despite being much younger. She focuses on him from time to time, to make sure he is keeping up with them, that they are not shoving him or denying him the ball. But her brother holds her attention only briefly before she returns to follow the movement of the eldest Ali boy, who weaves through the rest of the boys with an ease that looks graceful to her. From where she watches, it appears that the others are afraid of him or in awe of him — they seem reluctant to steal the ball, they cheer louder when he scores.

And he scores often. She tugs at the knot of her scarf again. It is a hot day. Abbas Ali, the eldest Ali boy, is the only one in the entire community Hadia has spent years maintaining a secret admiration for. She is not alone. The other girls have not been nearly as reticent. Already, he has a reputation in the mosque among the girls. He is kind to the youngest girls, pathetically adored by the girls his age, and even the older, teenage girls tend to comment on how incredibly good looking he will be when he grows up — sometimes to his face, because he is thirteen and so much younger than them, and that kind of compliment is not yet inappropriate. Hadia is among the adorers his age, and her mosque friends share anecdotes about him in the bathroom, magnifying his inconsequential actions: Did you see how he asked Zainab if there was any tea left in the ladies’ section?

To speak of it would be to lessen what she is beginning to feel.

She finds them foolish. She has no interest in engaging with the other girls and their childish fervor, their embarrassing giggles and obvious whispering. She refuses to add to his awareness of the effect he has on girls, refuses to speak out loud her thoughts on the matter — she has not even told Huda, with whom she shares everything. To speak of it would be to lessen what she is beginning to feel.

She is ashamed by how she watches him. By the details she notices. The sweat that glistens on his neck. The way he wipes his forehead with the back of his hand. His voice commanding the other players on the court. How they listen to him, and how, when the voices drift toward her, she knows which one is his. The few seconds when he lifts his shirt to wipe his face. She looks away then, before looking back, despite herself, a heat rising to her face. He is still young, skinny, she thinks. She is still just a girl, crooked teeth and bushy eyebrows, dressed in loose clothes her mother picked for her, a shirt that falls just above her knees, jeans a size too big, to ensure any hint of her body is hidden. Not the kind of girl a boy like the eldest Ali boy would ever notice. But still. The boys stop to take a break; some head for their water bottles and others lean forward and rest their hands on their knees, breathing heavily. Amar picks up the basketball before it rolls off the court and stands beneath the hoop, begins to practice. The eldest Ali boy looks over at the picnic table. At her. She looks away.

After the bell rings, she takes her time walking into the mosque where their classes are held. The other girls go on ahead, their steps quickening from the awareness that Quran class is next and the Arabic teachers are all so strict and punctual. Hadia fiddles with her scarf, untying it and retying it again. The knot under her chin feels heavy whenever she thinks of it. In the lobby that contains cubbies for all the shoes, she removes hers slowly, loops two fingers in the straps and tucks them away. The lobby is the only section of the mosque, besides their classrooms during Sunday school, that isn’t segregated. Everyone seems to slow when they are in the lobby, linger, wanting to take advantage of the brief moment when the veil between the genders is lifted. The boys who played basketball file in, sweaty and playfully shoving one another and kicking off their shoes before running to class. They do not notice her. The eldest Ali boy enters and next to him walks her brother. Amar is looking up at him in the way he would often look up at Hadia, when they were younger and her ability to make up new games mystified him. He has not looked at her that way in months, has stopped hovering in her doorway before his bedtime to tell her some trivial detail of his day.

As they approach, Hadia is suddenly more aware of herself, if only because of the eldest Ali boy’s presence in the room. This is my body, she catches herself thinking for the first time as he walks toward her, her heartbeat quickening and a drum gently throbbing in her ears. These are my skinny arms, my limbs, my skin he sees. It is thrilling — the sudden realization that beneath the layers of cloth, she has a body, a beat, a drum.

He gives her the kind of smile that girls gather in the bathroom to talk about, hooks his arm around Amar’s neck and says to her, “Your brother’s not so bad, you know.”

Your brother, he said. Your.

He announces to the few other boys that remain in the hallway that Amar will be on his team from now on. He pulls Amar closer to him for a moment before letting go. And it is that subtle display of affection for her younger brother that makes Hadia look at him in another way, aware of not only his eyes and how startling they are, or how he makes everyone in their Sunday school classes laugh, but also of how kind he is, how good.

Amar has a stunned look he tries to conceal; he busies himself by kicking his shoes into a cubby, smiling the whole time to himself. The eldest Ali boy walks into the corridor and heads to the Quran class that Hadia will soon be late to. Lately, Amar has had a rough time at school and difficulty keeping friends. Toward the end of last year, his grades had plummeted like never before, he had lost what little motivation he might have possessed, and his third grade teacher decided it would be best for him to repeat the year, considering he had done terribly on almost every single test. He has just begun third grade again. Amar looks at her and his smile widens before he rushes to his own class. She stands in the empty lobby, taking in the silence and the scattered shoes.

When she enters the classroom she spots the only empty seat, in the front row of the girls’ section, just behind the four rows of boys’ desks. The boys have the first few rows reserved, so that the order of the classroom may be maintained, so they cannot look at the backs of the girls at their desks and get distracted. Girls are not like boys, they are told, girls have control over their desires. It is up to the girls to do what they can to protect the boys from sin.

Sister Mehvish, their Arabic teacher, is the strictest of them all. She has a thick Arabic accent and a mole the size of a little grape on her upper lip.

“So gracious of you to join us, Sister Hadia,” Sister Mehvish says. “Why don’t you begin our class by reciting the surah you had to memorize.”

Everyone turns to look at her. Her face burns when she sees that the eldest Ali boy is looking, too. Hadia confesses she was unable to finish memorizing the surah, a lie she tells to save herself from the greater embarrassment of having to recite it aloud, drawing even more attention to herself, risking the possibility of fumbling the correct pronunciation, and the look she knows she will get from the other students who, as usual, have not bothered to memorize it at all.

“Of course you didn’t,” Sister Mehvish says, and some of the students snicker.

The only empty seat is directly behind the eldest Ali boy’s. He leans back in his chair, turns to face her when she sits, and she catches some sympathy in his eyes — but by the time she has settled and he has turned to face the teacher, she realizes it could easily have been pity. He rocks in his chair throughout the lesson, taps his pen against his blank binder paper, and she finds it hard to concentrate on the Arabic words Sister Mehvish is writing on the chalkboard. She remembers his arm around Amar, the points he scored, the moment he looked to her from the court, the vein in his neck, the skin revealed when he lifted his shirt — she feels instantly and intensely guilty for storing away that brief glimpse of his skin, especially ashamed that it has come back to her in a class for learning the Holy language, Holy texts. She does not recognize herself, and tugging on her loose sleeve so it covers her hands, she does not know if she likes herself. But he has a small speck of a birthmark where his hair meets his neck in the shape of a strawberry, and every so often he runs his hand through his hair, then lets his hand rest at the back of his head, so close that she would hardly have to stretch to touch him if she dared. Twice, she thinks he will turn to look at her, but he does not.

When the class is over everyone stands, no one faster than Hadia. The eldest Ali boy turns to her, nods toward Sister Mehvish, and rolls his eyes. That drum in her body again. Sister Mehvish has her back turned to the class and is erasing the words that look like scribbles from the board, creating a cloud of white dust. Hadia looks back at him. He has not looked away from her. He pulls an almost empty packet of gum out from his pocket and removes the last piece, a stick wrapped in silver foil, and extends it to her, his palm open, his eyebrows raised. Hadia reaches for it, her fingers lightly graze the surface of his palm. She wants to say thank you but does not, she can feel her face getting warmer, she fears he will notice a change in color, so she offers a small, quick smile and walks away. Her classmates have not noticed and Hadia looks up to where she imagines God is, sometimes a spot on the ceiling, other times a patch of brilliant blue in the sky, to thank Him for the moment passed unseen. She doesn’t want to be the subject of the next story they share in the bathroom: Did you see how he offered Hadia a stick of gum?

In the corridor light, the silver wrapping of the gum gleams. She tucks it into her pocket like a secret. ●

This post has been updated and re-published with new header art as part of the 2019 One Book, One New York program.

Illustrations by Amrita Marino for BuzzFeed News.

Copyright © 2018 by Fatima Farheen Mirza. From A Place for Us by Fatima Farheen Mirza (Hogarth, June 2018).

Fatima Farheen Mirza is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she was a Teaching-Writing Fellow. She has taught creative writing courses at the University of Iowa, Iowa Young Writers' Studio, and Catapult. She was awarded the Michener-Copernicus Fellowship in 2016 and The Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Creative Achievement from The University of California, Riverside. She has received residencies from The Marble House Project and The MacDowell Colony. She currently lives in Brooklyn. A Place For Us is her first novel.