Each episode of TLC’s long-running docuseries My 600 lb. Life begins in the same fashion: with a grunt and a sigh. My 600 lb. Life purports to be the standard reality television series, no different than The Real World or the Love & Hip Hop franchise, except the subjects of the camera’s intense gaze are people who weigh more than 600 pounds and, in extreme cases, close to 1,000 pounds. Across both elements of the franchise — My 600 lb. Life and My 600 lb. Life: Where Are They Now? — we’re introduced to people classified as “morbidly obese,” meaning they’re 100 pounds or more above their “ideal” body weight, without regard for how that designation is used to stigmatize people.

For one year — two years if they’re featured on Where Are They Now? — we follow each patient as they’re guided through a weight-loss program created by Dr. Younan Nowzaradan, a surgeon who behaves as if he’s the Gordon Ramsay of weight loss. Nowzaradan is known for being blunt (and calling it being honest), acting in ways that can seem incredibly cruel, and literally telling his patients they’re one extra cheeseburger away from becoming immobile—if they’re not already—and dropping dead. His high-protein, low-carb diet program, which encourages patients to consume 1,200 calories a day, is one of the few in the United States that focuses specifically on people for whom it’s deemed too risky to have bariatric surgery because of their size.

Dr. Now, as he’s often called, requires his patients to lose a certain amount of weight before performing a gastric sleeve or full gastric bypass to ensure the surgery is as safe as possible and they have less chance of dying on the operating table. Over the course of two hours of television designed to humiliate, we follow each patient’s journey—beginning with said fat person, who is identified by their first name, age, location, and approximate weight, typically struggling to get out of bed, use the bathroom, and shower. Sometimes, the subject— not a person deserving of dignity, but a subject—can walk to the bathroom on their own. But often, a caretaker—their child, a neighbor, a romantic partner, a next-door neighbor— helps them sit up, helps them walk to a portable toilet, and then helps them into the shower.

Sometimes, they have to literally shit in their beds because they’ve completely lost their ability to walk. Once they’re in the shower, the only thing preventing their most intimate parts from being displayed is a small blur similar to the one TV shows use to cover a raised middle finger. Subjects who are able to shower treat us to a close-up: soap pouring over their body as they attempt to clean between every fold on their flesh because, as many of them say, their bodies may develop an infection if they’re not immaculately clean. Once that’s done, it’s on to the most important thing: eating. The camera zooms in as the subject eats whole slabs of bacon, boxes of doughnuts, multiple pizzas, fast food, fast food, and more fast food.

From the show’s perspective, we have to see these subjects eating because that’s the only way the disgust will really sink in. These are fat people! the show tells us. Look at them! Do you want to be like them? Stop eating! It’s at this point that the show fully loses itself to depravity. The subject details their entire life story from childhood, mostly focusing on how and why they’ve gained weight. The subjects were once, as they often put it, “normal size”—until something traumatic caused them to begin gaining weight. The show reserves between three and five minutes for them to document their worst experiences—incest, rape, the untimely death of a parent, being rejected for being transgender—and then conveniently tucks those tears away, because that trauma is deemed a distraction from the overall point of the show. Yes, their pasts are sad and all, but we’re here to poke fun at these fat people, and we shouldn’t ever forget it.

These are fat people! the show tells us. Look at them! Do you want to be like them? Stop eating! It’s at this point that the show fully loses itself to depravity.

By the time our subjects arrive in Houston to meet with Dr. Now, they’ve all declared that they’re at their wit’s end. They’re going to die if they don’t lose weight, and he’s their last hope before they eat themselves into an early grave. Dr. Now is sure to reiterate that—over and over again—as the subjects break down in front of him, begging for his help and saying that they have no idea how they got to the point of being bedridden. He doesn’t peel back this layer of the onion either—being fat is enough. We don’t see him sending his patients to psychotherapy to address their issues or immediately referring them to a professional nutritionist who can help them learn how to nourish their bodies without “overeating.” Instead, he gives them a weight-loss goal—lose 50 pounds, 60 pounds, or 70 pounds in the next two or three months—and a strict diet. Eat 1,200 calories, walk every day to strengthen your body, and you’ll be good as new, mind and emotions be damned.

Following the success of My 600 lb. Life, TLC released Too Large, another reality TV show about fat people losing weight, in 2021. Though it has the same premise as My 600 lb. Life, it isn’t as degrading, because Dr. Charles Procter, the bariatric surgeon who oversees the show’s weight-loss program, helps the patients in every aspect of their lives instead of berating them for ratings. He recognizes that many of his patients—like Corey, who gained weight after his mother rejected him because he’s gay—need more than a strict food regimen. They need a doctor who cares about their overall well-being. While Dr. Now typically doesn’t send his patients to psychotherapy until they’re in danger of regaining the weight they’ve lost, Dr. Procter immediately refers his patients to a counselor. While Dr. Now pokes fun at his patients who are struggling with their hygiene, Dr. Procter talks to his patients about the benefits of hiring an in-home health aide.

While both shows treat fatness as a humiliating condition, Too Large has found a way to humanize the people it follows, allowing them to keep their dignity. It’s an exception in a larger pool of shows that would rather embarrass fat people than help them in whatever way they need, whether it’s losing weight or getting a housing voucher to prevent them from becoming homeless. There comes a time within these shows when the subject is encouraged to “debut” their smaller body, showing off their new figure to family members and friends who’ve been waiting for a reveal that proves their loved one has been cured. These previously bedridden people are now able to fit into clothes that used to be inaccessible to them. They’re off crutches, out of wheelchairs, and able to walk around their neighborhood. Their children respect them again because they no longer have to take care of them. They start dating and, sometimes, they fall in love. They become visibly confident, wearing flashier, splashier shirts and bolder wigs, putting on a piece of jewelry or two, adding an extra switch to their walk.

These shows tell us that losing weight not only lengthens a person’s life but also gives them the confidence to face life’s obstacles, take a risk on love, and make others proud in the process. What they don’t tell us, however, is the moral conundrum that accompanies shows airing some people’s last moments for the sole purpose of poking fun at them. Multiple patients have died either while filming My 600 lb. Life or in the months and years afterward, and their deaths are nearly always attributed to “obesity.” Many of them die from heart attacks, a fear that plagues me as someone with heart failure, so Dr. Now is often praised in Reddit forums for attempting to save their lives. But what kind of savior would flaunt a person’s sickness on television for ratings? Apparently, one who understands that fat jokes are a specific kind of currency that can always be cashed in season after season.

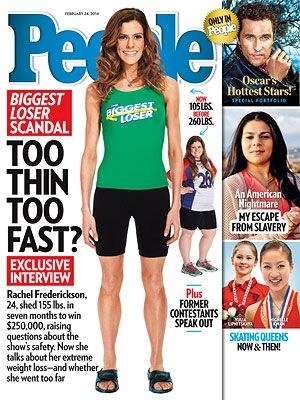

My mother and I often used to joke that we should attempt to be cast on The Biggest Loser, especially when the show was in its heyday on NBC. “We should throw our name in the ring,” my mother would say to me half jokingly. “Oh no, I don’t think so! You won’t embarrass me on television. Plus, we’re not even fat enough. They’d kick us off in two weeks.” The Biggest Loser is a reality TV show that rewards people for losing weight. The person who sheds the most pounds, no matter how it’s attained or if it’s sustained after the season ends, is awarded a cash prize and the adoration of millions of television viewers who just can’t believe how quickly they dropped all those pounds. For several years, People magazine would dedicate a cover to debuting the svelte new body of each season’s winner. During the show, each contestant would discuss how their weight was holding them back in various elements of their life—from their ability to find and retain gainful employment to their mental health. Once the number on that scale is lower, the world is suddenly more open than it has ever been before. Their weight—their “super obesity,” if that phrase floats your boat—is preventing them from living even a marginal portion of the lives that should be open and available to them.

But in order to get access to that brand-new life, there’s a grueling gauntlet fat people must endure. We must push our bodies to their limits on national television to show the normal, thinner world how miserable we are in our current states. We must prostrate ourselves in front of those who can help us see the error in our ways—in this case, the bariatric surgeons and fitness coaches who will scream at us until we see the light. And then, we must restrict how much food we consume and exercise excessively until we lose enough weight to qualify for the cover of People or for bariatric surgery.

For many years, I avoided shows like My 600 lb. Life. Though my mother, who has experimented with nearly every diet on the market, was a devoted viewer of what I’ve referred to as the fat reality TV show vortex, I’d leave the room when The Biggest Loser or True Life: I’m Fat as Hell graced our screen. I did this for myriad reasons, but let’s start with the obvious. These shows are ridiculously exploitative. People lose and gain weight all the time, but shows that use this premise to drive ratings—whether it’s WE tv’s Mama June: From Not to Hot or TLC’s Wednesday slate of fat-focused television—reinforce the very idea that fat bodies are a problem to be solved, a conundrum in dire need of being fixed. Even the milder fare, like 1000-lb Sisters and One Ton Family, which are exactly what their titles suggest, feed into this idea. Eventually, though—as is often the case when you’re living in the same home with someone—my mother’s consumption interests bled into my own. My 600 lb. Life became one of the shows that we shared, that we are within the universe of, that we have a secret language about. “Have you watched our show?” became second nature for us on Wednesday nights after we’d both finished working.

People lose and gain weight all the time, but shows that use this premise to drive ratings reinforce the very idea that fat bodies are a problem to be solved, a conundrum in dire need of being fixed.

My obsession was sparked by a single episode: A 42-year-old Black woman named Octavia lives in Kansas City, Missouri, with a roommate. She weighs more than 650 pounds and hasn’t left her bed in nearly three years, so she uses a pail at the end of her bed as a toilet. Her roommate, who moved in with her when she became bedridden, brings her a bucket with soapy warm water so that she can wash as much of her body as possible. The best moment in Octavia’s entire day is when her sister brings her niece and nephew to visit her. Their visits increase her social interaction and allow her to pressure her sister to purchase her lunch and dinner. Candy is the language she shares with her niece and nephew, whom she allows to reach into a huge plastic bag and remove a piece or two to enjoy.

Though Dr. Now tells Octavia that it’s dangerous for her to move to Houston to be near his clinic, she disobeys him, packs up her apartment—her bedroom had been in the living room to begin with—and rides in the back of a van, a trip so painful that she complains about her aches and pains the entire hours-long ride. When she arrives in Houston, she’s immediately chided by Dr. Now for making the trip, and then shot down. Because Octavia hasn’t lost any weight since their initial phone call, she’ll need to lose more than 50 pounds in two months in order to qualify for bariatric surgery. Dr. Now is worried about Octavia’s overall health because she’s unable to stand or walk, so he hospitalizes her to speed up her weight loss and help her begin walking. Though not every patient is hospitalized, many of them are, depending on the overall state of their health. Octavia’s put on an intensely restrictive diet, and nursed—tough love, be damned—back to some semblance of health. By the time she leaves the hospital, she’s lost more than 60 pounds and she’s able to stand for a short period of time and take a couple of steps. It isn’t enough for bariatric surgery, but it’s enough to be released from the hospital and prove to Dr. Now that she can lose weight on her own.

But when she gets home, she gains weight instead. When she comes to the clinic for her next weigh-in appointment, Dr. Now tells her she’s always blaming someone or something for her weight gain instead of taking control of her health. In his eyes, Octavia’s lack of discipline is the problem and it’s her lack of discipline that will eventually kill her. As I watched the episode, I felt frustrated by Octavia. Why couldn’t she just say no to the “unhealthy” foods her roommate is bringing into their apartment? Why can’t she just force herself to walk, even if it’s just from her bed to her front door and back? Though I know weight loss is never as easy as doctors purport it to be, I still bought into Dr. Now’s manipulative rhetoric. After all, lose weight, save your life doesn’t seem like that difficult of a mandate. I can remember turning to my mom on the couch and asking, “Does she want to live or not?” She just shook her head. By the end of that episode, I was hooked. I went back and watched every season of the show, and I kept cycling through those same emotions: jubilation for those who follow Dr. Now’s program and lose weight and frustration with those who just can’t seem to get themselves together enough to follow his diet.

For those seeking Dr. Now’s care, eating “healthy” and exercising isn’t enough. I know that. And yet, watching fat people try and fail to lose weight still ensnares me so much that My 600 lb. Life has become appointment television for me. I’ve been studying fatphobia for so long that I can pinpoint obscure fatphobia in the most “body-positive” pop culture. I know My 600 lb. Life shouldn’t be airing on television. I know TLC has built its wealth on the literal backs of people from marginalized communities, including trans people (My Pregnant Husband; I Am Jazz), little people (Little People, Big World; The Little Couple; and 7 Little Johnstons), undocumented immigrants (90 Day Fiancé, anybody?!), and fat people, but somehow, a network that puts a bull’s-eye on the back of the very community I write and advocate for draws me in week after week.

As ashamed as I am to admit this, there’s a particular two-part episode of My 600 lb. Life that I’ve watched, repeatedly, both on TLC and in perpetual reruns on Hulu. It features Janine, a woman in her mid-fifties who is only able to transport herself by motorized scooter from her bed to her bathroom and to a local McDonald’s and back. There’s no doubt Janine is lonely, and she repeatedly says that she’s miserable in her body. She lives alone in Seattle, hundreds of miles from her siblings, who reside in Colorado. Both of her parents, who adopted her when she was a few months old, are deceased, and she ponders if they ever really loved her to begin with. She believes they intentionally treated her differently than her siblings. Knowing that Janine’s biological mother was fat, her adoptive mother put her on a diet at the age of four, and she’s been on the wretched dieting path ever since.

Janine is so lonely, in fact, that her cat is her only company, and she carries on full conversations with him as she eats waffles covered in strawberries and whipped cream. If My 600 lb. Life were actually invested in the health of its subjects, Janine’s tormented past—being abandoned, being adopted into a family that cared far more about the physical size of her body than her mental health, and being so isolated that she has to hire a stranger from the internet to travel with her to Houston—would’ve been Dr. Now’s primary focus. Instead, Dr. Now repeatedly shames Janine for not seeking care sooner. It begins when she attempts to travel to Houston by plane and suffers a debilitating panic attack that forces her to be carried off the plane on a stretcher and hospitalized. Next, Dr. Now yells at her for not abandoning her motorized scooter, though it’s clear that she’s unable to walk without it. When she begins telling Dr. Now’s nursing staff that she can’t walk without assistance, he calls her “delusional.” We see, repeatedly, that Janine is calling out for help, and no one is willing to step in and intervene in a way that preserves her dignity.

It takes two hour-long episodes, multiple breakdowns, and an invasive procedure that literally causes her hair to fall out for Janine to be taken seriously enough to meet with a psychotherapist, who simply tells her to forgive herself for everything she’s done to “punish” her body. I have watched this episode of My 600 lb. Life so often that I can recite it nearly word for word, starting with the moment Janine uses a metal contraption of sorts to wipe her butt and says, with jest and in full view of the camera, “Want to know how a fat woman wipes her ass? This is how.” There’s no logical reason for me to be so obsessed with this show—even browsing Reddit threads during and after episodes to gauge what other people are saying, and crying when episodes end with the subjects dying.

As I absorb the subjects’ stories, no matter how tragic they are, I get to reinforce to myself that I’m superior because my weight is “under control.”

But as I’ve watched and laughed and cried, it’s become clear to me: feelings of superiority can breed the most monstrous behavior. Fatness is intertwined in my very being; I don’t know who I am if I’m not fat. But I’ve also prided myself on not being that fat. Many fat people have that moment when we walk into a room—sometimes with strangers, sometimes with friends— and we look around, sizing up everyone around us and attempting to figure out if we’re the largest person there. For me, that moment dictates a lot about what happens next. If I’m the largest person in the room, I feel an innate urge to shrink, to make myself as unobtrusive as possible. I position myself in a corner where nobody can see me, lean against the wall, and pretend as if this is natural posturing.

But on the rare occasion when I’m not the largest person in the room, when I size everyone up and gleefully notice someone bigger than me, it imbues me with a wicked, false confidence: “Now there’s someone else to focus their attention on.” I no longer have to be a wallflower because someone else can fill that role now. In these moments, I siphon that other fat person’s energy. Suddenly, I have an effervescent buoyancy, and I feel confident enough to socialize, to speak to strangers, to put my shoulders back, hold my head high, and own a room.

That same dynamic functions in my obsessive, repetitive watching of My 600 lb. Life. As I absorb the subjects’ stories, no matter how tragic they are, I get to reinforce to myself that I’m superior because my weight is “under control.” I’m still mobile. I can still walk into a plus-size store and purchase clothes. Doctors discriminate against me, but I’m not at the mercy of any particular provider to receive the care I need. In other words, I’m able to create distance between the fat body I inhabit and their fat bodies. I know I gain nothing from investing in fatphobia and perpetuating it toward those larger than me, and yet, it’s much easier to laugh at fat people on television than to think about those laughing at me.

Dr. Now routinely tells his show’s subjects that they smell, that their bodies have an odor, that they could be living a better life if they just slimmed down. He often couches these insults in humor and feigned concern, pretending as if his cruelty is really about preserving his patient’s life. The reality, however, is that he’s able to play up their shortcomings for the camera—bringing in equal amounts of ratings and disgust from viewers who have bought into the idea that it’s only their eating habits and never their genes or their trauma that have brought them to the point of immobility. It’s painful to admit that I feel morally superior to fellow fat people on reality television. I am sure—nearly positive— that this will disqualify me as a fat-positive activist. People might screenshot parts of this essay and spread it on social media to prove that I’m a fraud or that I purport to care about fat people in public, but in private, I am just as complicit in fatphobia as the very people and institutions I criticize.

Unlearning is a difficult process. It first requires you to look in the mirror, admit that you’ve benefited from a system at the expense of other, more marginalized groups, and then actively work to create new commitments and behaviors that dismantle that system. But when you’ve been indoctrinated into a fatphobic theology where thinness is the god to be idolized, and every element of your life underscores this worldview, it becomes easy to pick apart people whose bodies are more unacceptable than yours, even if only slightly. Peering out the window and asking, “Do I walk like her? I hope not. She’s waddling,” covers my own fear about being the person being judged in the way I’m judging. I deploy these skills, forged in fire and struck against iron, while watching My 600 lb. Life. I’m especially guilty of doing this when said person refuses to follow Dr. Now’s program and continues to either gain weight or lose it more slowly than Dr. Now would prefer. “That’s an absolute shame” is one of my favorite retorts, followed by “Well, that episode was a waste of time. They didn’t lose any weight!” I couch these barbed comments in the additional skin I’ve formed over time. I’ve learned that it’s better to strike first, to preemptively project before the echo can return, even if it comes at the expense of your self image. You see, if I am obsessed with this show, then no one can be obsessed with me. ●

From Weightless by Evette Dionne. Copyright © 2022 by Evette Dionne Excerpted by permission of Ecco, a division of HarperCollins. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Evette Dionne is a journalist, editor, and culture critic. She is the former editor in chief of Bitch Media and the current executive editor of YES! Media. Lifting as We Climb: Black Women’s Battle for the Ballot Box, Dionne’s middle-grade nonfiction book about Black women suffragists, was nominated for a National Book Award and won a Coretta Scott King author honor. She lives in Denver with her partner and her two pets and they are likely listening to Beyoncé right now.