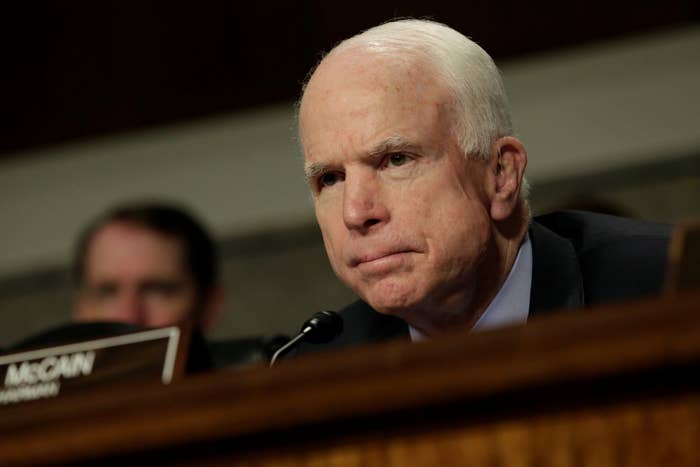

Republican Sen. John McCain died Saturday at the age of 81. The veteran US senator, who spent five years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam as a young Navy pilot, had been diagnosed with brain cancer in July 2017.

McCain's Senate office confirmed his death in a statement. "With the Senator when he passed were his wife Cindy and their family," it read. "At his death, he had served the United States of America faithfully for sixty years."

McCain, the senior senator from Arizona, a father of seven, and a former Republican presidential nominee, served in Congress for 35 years. Most recently, he was the chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

McCain was a war hero turned senator, nicknamed a “maverick” for his no-nonsense style and willingness — sometimes to the chagrin of his staff and fellow Republicans — to speak his mind. Following his diagnosis, McCain continued to serve in the Senate as he received treatment, often attending votes in a wheelchair. Even after he was diagnosed, McCain continued to make waves by bucking his own party — including memorably voting against his party’s plan to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

McCain had been absent from Washington since December 2017. On Aug. 24, his family announced that he was ending treatment for cancer. “In the year since [his diagnosis], John has surpassed expectations for his survival. But the progress of disease and the inexorable advance of age render their verdict,” the family said in a statement. He died the following day.

"My father's passing comes with sorrow and grief for me, for my mother, for my brothers, and for my sisters," McCain's daughter, Meghan McCain, said in a statement, "He was a great fire who burned bright, and we lived in his light and warmth for so very long. We know that his flame lives on, in each of us. The days and years will not be the same without my dad — but they will be good days, filled with life and love, because of the example he lived for us."

Even after he left Washington, McCain remained an important voice on issues such as foreign policy and torture, opposing President Donald Trump’s pick of Gina Haspel to be CIA director because of her involvement in the agency’s torture program after 9/11. After he announced his position, a White House aide said McCain’s opposition to the nomination didn’t matter because “he’s dying anyway,” prompting outrage from Republicans and Democrats alike. (The aide was later fired.)

At home in Cornville, Arizona, McCain spent his final months with family and friends reflecting on his lengthy career and broad legacy. In a memoir released in May, McCain made a plea for civility “even in times of political turmoil such as these,” urging Americans to “recover our sense that we are more alike than different” and warning against isolationism, restating his long-held belief that the US should occupy a prominent place in the world — positions that have often separated him from the president’s own rhetoric.

“Before I leave,” he wrote, “I'd like to see our politics begin to return to the purposes and practices that distinguish our history from the history of other nations. ... Whether we think each other right or wrong in our views on the issues of the day, we owe each other our respect, as so long as our character merits respect, and as long as we share for all our differences, for all the rancorous debates that enliven and sometimes demean our politics, a mutual devotion to the ideals our nation was conceived to uphold, that all are created equal and liberty and equal justice are the natural rights of all.”

In July, the US Navy added McCain’s name to the warship named for his father and grandfather, both of whom served as admirals in the Navy. The USS John S. McCain was rededicated to all three men in a ceremony in Japan to honor his service.

“As a warrior and a statesman who has always put country first, Sen. John McCain never asked for this honor, and he would never seek it,” Navy Secretary Richard Spencer said at the time. “But we would be remiss if we did not etch his name alongside his illustrious forebears, because this country would not be the same were it not for the courageous service of all three of these great men.”

Asked last September, not long after his diagnosis, how he'd like to be remembered, McCain told CNN, “He served his country and not always right. Made a lot of mistakes. Made a lot of errors, but served his country. And I hope we could add honorably.”

McCain remained resilient throughout his treatment, adopting, according to longtime friend Sen. Lindsey Graham, a forward-looking attitude. “We talked about what we could do this summer. Maybe doing some events, if he gets a little stronger, at the McCain Institute. We were talking about the future,” Graham told CNN in May. “We're not talking about funerals.”

Other fellow senators — some friends, others occasional foes — spent recent months reflecting on McCain’s life and legacy. “I came here five and a half years ago never having met John McCain, and have gotten to know him over that period by serving on his Armed Services Committee, by traveling with him,” Maine Sen. Angus King, an independent who caucuses with Democrats, said on the Senate floor in May. “I told some friends in Maine over the weekend, traveling with John McCain is like a long march with Paul McCartney. You work hard, and everyone in the world knows him. And he is an extraordinary leader, and one of the most principled people I’ve ever met.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who fought McCain on what would become a signature piece of campaign finance legislation, the McCain–Feingold Act (“He won and I lost,” McConnell said), visited McCain in May. “We had some laughs and even reminisced about the battles; sometimes we were on the same side, and sometimes we weren’t. But one thing about our colleague, John McCain — you’d rather be on his side than not,” McConnell said on the Senate floor after returning from Arizona.

McCain was born in 1936 at a military base in the Panama Canal Zone — an American territory at the time — where his father was stationed. McCain, who comes from a line of distinguished Navy officers, grew up moving from one military base to another across the US and overseas.

In 1954, McCain began studying at the US Naval Academy, where he earned a reputation as a troublemaker. It was during his time in Annapolis that he met Carol Shepp, who would later become his first wife. McCain’s first child, Sidney, was born in 1966, and he adopted Carol’s two children, Doug and Andy, from a previous marriage.

In 1967, McCain — by then a combat pilot serving in the Vietnam War — narrowly escaped a massive explosion aboard the USS Forrestal that killed more than 130 people. McCain was hit with shrapnel from the blast.

The major turning point in McCain’s life came just a few months later. McCain was flying a bombing mission over Hanoi when his plane was shot down by a surface-to-air missile. With multiple broken bones, McCain was captured by the North Vietnamese, who tortured and beat him over more than five years as a prisoner of war.

During his captivity, McCain was offered early release, but he refused. “I just knew it wasn't the right thing to do,” he told the Arizona Republic in 2007.

McCain was finally released in 1973 and returned home a hero. He was awarded the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Bronze Star, and the Legion of Merit for his service during the war. In Congress, he was a major opponent of the use of torture, given his experiences.

McCain and his wife Carol divorced in 1980 and he married Cindy Hensley, heir to a large Arizona beer distributorship, shortly after. Together, they would have Meghan, Jack, and Jimmy, and adopt Bridget from Bangladesh.

Though he had been given a taste of Capitol Hill while serving as the Navy’s liaison to the Senate before his retirement at the rank of captain in 1981, it was in 1982 that McCain’s political career truly began, when he was elected to the US House of Representatives for Arizona’s 1st Congressional District.

In 1986, McCain ran to represent Arizona in the Senate and won. Throughout his time in Congress, he earned a reputation as a “maverick” for his tendency to speak his mind and publicly call out members — even presidents — of his own party. He was a frequent presence on national television and was a reliable quote for reporters covering the US Senate and his campaigns. That reputation led to the creation of the “Straight Talk Express,” a bus he drove to campaign stops during both of his presidential bids.

McCain’s presidential aspirations would go unfulfilled, however. He ran for the Republican presidential nomination in 2000 and lost to George W. Bush, who would go on to win the presidency. In 2008, McCain clinched the nomination but lost the general election to Democrat Barack Obama. McCain chose Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin as his running mate that year, a move many viewed as damaging to his campaign, but one that launched her career in national politics.

During his years in the Senate, McCain had a major impact on foreign policy, as the chair of the Armed Services Committee and one of the party’s highest-profile hawks.

Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, McCain joined forces with then–Democratic senator Joe Lieberman to push for a bipartisan commission to prevent future attacks, which became the 9/11 Commission and helped to reshape the US government’s intelligence and national security structure.

McCain’s name is affixed to another major piece of legislation from that era, the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, or “McCain–Feingold,” as it’s more commonly known. McCain, along with then-senator Russ Feingold, a Wisconsin Democrat, pushed for the legislation to add new limits to campaign finance laws for years. It passed in 2002 and limited corporate and national party spending in federal elections, among other things. The bill also mandated candidates’ use of disclaimers at the end of their ads affirming that they “approve this message.”

However, parts of the McCain–Feingold law dealing with corporate spending in elections were overturned by the Supreme Court in the groundbreaking Citizens United v. FEC case. That decision, combined with the law’s restrictions on political parties, have, in part, been blamed for the resulting rise in campaign spending by outside groups.

More recently, McCain was a member of the “Gang of Eight,” a bipartisan group of senators who introduced comprehensive immigration reform that passed the Senate in 2013. But the bill never passed the House and the framework was ultimately abandoned.

“It’s pretty hard to think of any serious issues facing our nation without recalling the role that John played in so many things that are important to our country,” McConnell said in his floor speech in May, recalling how Republicans viewed McCain as “the shadow secretary of state during the Obama years, as he traveled the world — sometimes on a long weekend — to some of the least desirable places to visit.” McConnell also spoke about McCain’s years of work on veterans issues.

“At this point in his life he obviously has a little time to sit, rest, and reflect under that desert sky,” McConnell continued. “To simply take in the beautiful, peaceful nation he’s worked so hard for so long to protect and pass on to our children.”

“I didn’t want to miss the opportunity to tell him how much his friendship meant to me,” McConnell said. “So that’s why I was out there this weekend. And while I was there, I said I was confident I was speaking for everybody in the Senate. And conveying our deepest respects to him for all he’s done for this country during a truly extraordinary life.”