Donald Trump’s plan to end birthright citizenship by executive order was immediately denounced by legal scholars as an illegal intrusion on the Constitution’s 14th Amendment. But the United States knows something about ending birthright citizenship because it played an active role in helping another country bring it to a close — the Dominican Republic.

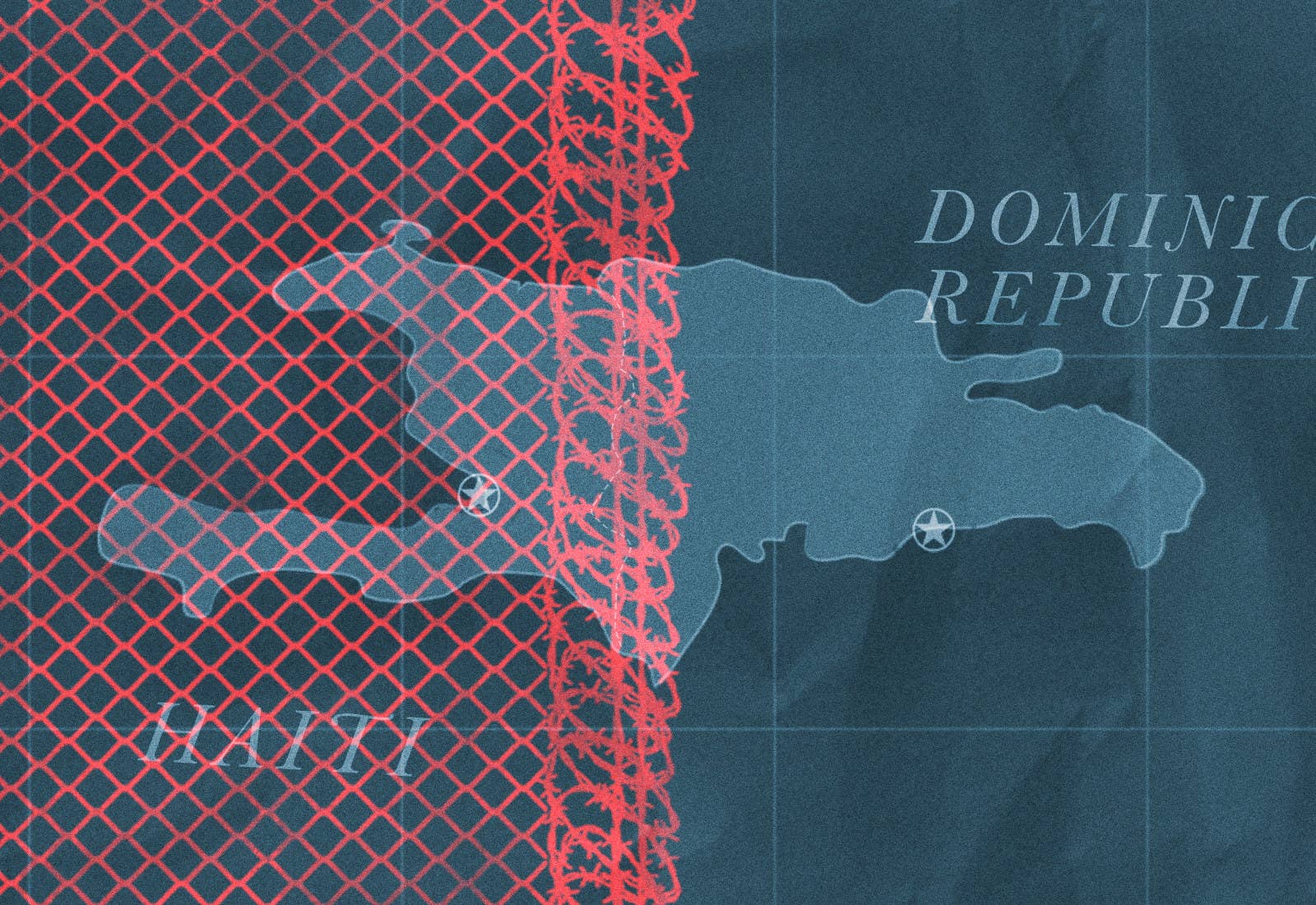

That role, which was unfolding before Trump became president, has long been the subject of criticism — from the Organization of American States, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and former Peace Corps volunteers who served in Haiti, which shares the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. Trump’s criticism of birthright citizenship and call for a wall on the US–Mexico border have renewed concerns that the US is inflaming the Dominican Republic’s already hostile xenophobic attitudes toward its Haitian minority.

Some also worry that what has happened there could happen in the United States.

“Before President Trump proposed the wall with Mexico, we in the Dominican Republic have been raising the need for a wall,” Pelegrín Castillo, founder of the National Progressive Force Party and a staunch supporter of a 2013 Dominican court ruling that effectively stripped citizenship from thousands of Dominican residents of Haitian descent, said in a recently published interview. “We see in the Trump administration and in the policies that he promotes an opportunity to rethink all these issues, because with the previous administration it was not possible.”

That’s a reference to the Obama administration, which opposed a Dominican law that eventually was used to strip citizenship from people who’d been born and lived in the Dominican Republic for their entire lives, but who could not establish with documents where they’d been born. During that same period, however, the US helped fund the Dominican military forces that carried out the forced repatriation to Haiti of thousands of people of Haitian descent who had never lived there.

The presence of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic has been a source of tension since the 19th century when Haiti occupied the Dominican Republic, then helped the Dominican Republic overthrow Spanish colonizers in the 1860s. In 1937, 20,000 Haitians were killed along the Haitian–Dominican border in what was known as the Parsley massacre, when Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered the deaths of anyone who mispronounced the Spanish word for “parsley” so that soldiers could tell whether they were Dominican or Haitian. Those who appeared to be the latter were killed.

But Haitians also were the primary source of cheap labor for Dominican sugar companies. Originally, this was seasonal labor; eventually, the workers stayed in the Dominican Republic. Dominican economic growth has continued to require cheap labor, and Haitians have played that part.

But many Dominicans resent the Haitians — not just the migrants, but Dominicans of Haitian descent — and that resentment has led to a series of Dominican actions intended to find a way to send Haitians and their descendants back to their side of the island. “In the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, [there was an] informal process in which a Haitian Dominican would show up, an official would take a look at him and say, you don’t look Dominican to me,” Ernesto Sagás, associate professor of ethnic studies at Colorado State University, told BuzzFeed News.

Under the Dominican Constitution, those born on Dominican soil were Dominican, even if their parents weren’t — unless the parent was “in transit” when the child was born. That exclusion dated back to the days of ships passing through. But well into the 20th century, it was being used to discriminate against Dominican citizens whose parents came from Haiti.

Officials “would argue that Haitians were in transit, regardless of how long they had lived there,” Sagás said. “They’ve been in transit for 20 years. How could that be? Doesn’t matter.”

In 2004, a new immigration law was passed that said that the “in transit” provision of the constitution applied to the children of undocumented workers, regardless of how long the undocumented workers had been in the Dominican Republic. In 2007, the Central Electoral Board — Junta Central Electoral, or JCE — began applying the 2004 law retroactively, refusing to issue or renew identity documents to Dominicans of Haitian descent born before 2004.

The JCE didn’t do that all on its own. The United States helped, under the guise of helping the Caribbean nation modernize its record keeping and investigating fraud. Marselha Gonçalves Margerin, a human rights lawyer and advocate who works on the issue of stateless people in the Dominican Republic, said it was US money that helped the Dominican Republic revise its record keeping to better track its citizens and more effectively strip citizenship from people it determined had been born of undocumented parents.

In a 2010 report, the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights was critical of the US’s role. “The US position on these issues has been ambiguous at best, as both USAID and State officials have publicly supported civil registry policies in the context of so-called anti-fraud reforms, and may in fact be providing technical assistance to advance the process,” the center concluded.

The State Department confirmed the assistance to BuzzFeed News, saying the effort was intended to reduce document fraud and, in the words of a spokesperson for the Western Hemisphere Affairs division, “enhance border security through the prevention of illegal drug smuggling, migrant smuggling, and human trafficking.”

But identifying alleged document fraud also played into another goal: identifying people who were not entitled to Dominican citizenship.

In 2010, the Dominican Republic changed its constitution to say that, if you are without papers, regardless of how long you have been in the country, your children are not citizens. In 2013, a newly created constitutional tribunal stripped citizenship from people whose parents were undocumented in a case known as La Sentencia. The ruling went back to 1929 and impacted thousands upon thousands of people.

People who “were born, grew up, served in the military, died Dominican … Whoever was not born from parents legally — a Dominican parent — those people were not Dominican, they had to apply [for citizenship],” Sagás said.

The constitutional tribunal had gone further than had been expected by the government, which now found itself with an international crisis on its hands.

“US human rights organizations were very vocal against the court ruling in 2013, and were very vocal in documenting some of the problems, particularly as it came into force in 2015,” Michele Wucker, author of Why the Cocks Fight: Dominicans, Haitians, and the Struggle for Hispaniola, said.

Under that pressure, the Dominican legislature passed a law that divided people affected by the court decision into Group A and Group B.

People in Group A were those who had documentation. Under the law, once the validity of their birth certificate had been established, their nationality could be restored. But people in Group B — “children of foreign parents in an irregular migratory situation” — had no such papers. They could apply for regularization of their status as migrants, and then, after two years, would be authorized to apply for Dominican citizenship.

Daniel Erikson, who served in the White House as special adviser to former vice president Joe Biden, said the law was seen as a “major step they took to mitigate what many saw as negative effects” of the 2013 court decision. But it also introduced a process that was “slow, cumbersome, not that well understood, [and] puts the burden of proof on individual instead of the state.”

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights went further, calling the law “an impediment to the full exercise of the right to nationality of the victims.” People who still faced the risk of deportation to Haiti, even if they themselves had spent their whole lives as Dominicans.

According to the International Organization for Migration, 40,000 people were deported from the Dominican Republic to Haiti between August 2015 and May 2016. Fifteen percent of those told the IOM that they had been born in the Dominican Republic.

Erikson recalled the Obama administration as “being quite critical of it at the time.”

Nevertheless, the reality remains that the security forces carrying out the deportations had been trained by and were at least in part funded by the United States.

That was a particular issue for former Peace Corps volunteers who wrote a letter of protest to the State Department. “The security forces that appear poised to carry out mass deportations within the country, including the US-trained border patrol agency, CESFRONT, have received more than $17.5 million in assistance from the United States since 2013, the year that the Constitutional Court handed down its ruling,” the letter read.

That letter called for an end to military aid to the Dominican Republic under US laws that prohibited assistance to any unit of foreign security forces suspected of violating human rights. The letter noted that the Inter-American Court of Human Rights had “called for redress to victims who suffered illegal deportations, the denial of identity documents, and arbitrary deprivation of nationality.”

But aid was not suspended. A State Department spokesperson said US officials determined then that cutting off military aid would be counterproductive. “Our assessment was that we would be better served by working with the Dominican Republic to address this situation rather than ceding the progress we were making with the Dominican military in the security sector by halting our military assistance,” the spokesperson said.

“Clearly, the United States has a checkered policy when it comes to aid and some of the foreign policy,” said Rose-Marie Belle Antoine, a law professor at the University of the West Indies and a member of an Inter-American Human Rights Commission delegation that visited the Dominican Republic in 2015. “It gives a certain amount of legitimacy to the regime and allows them to continue this facade.”

Deportations have continued, she noted, and the tensions around immigration status, nationality, and race are still “very bad.” “There have been some sort of cosmetic changes, but it hasn’t gone far enough,” she said.

And many worry that the Trump administration would be even less likely than the Obama administration to discourage the Dominican Republic from deporting people of Haitian descent. They note recent news stories about people who’ve long thought they were US citizens being denied passports because their births took place at home and were registered by midwives.

“The Dominican Republic has been a training ground for the nativists in the United States,” Margerin said.

“It’s clear Dominican politicians are not going to feel pressured by the Trump administration,” Erikson said.

But it isn’t just that US policy might embolden Dominican policy. It’s that Dominican policy, or a version of it, might become US policy.

“The Dominican Republic in a way foretold what was to happen in other countries,” Antoine said. “Even in the United States.” ●

CORRECTION

This piece originally included a photo of a Peruvian flag that was misidentified as a Dominican flag. That photo and caption have been removed.