On Feb. 17, 1997, at approximately 4 a.m, Audrey Polk was asleep in her sister's house in Detroit, Mich., when a stranger broke in, snuck into the room where she was sleeping, and sexually assaulted her. The mother of two young children called the police, who sent over some officers who happened to be up the road at Leo's Coney Island — a downtown staple — having a late-night snack.

As Polk remembered it, the police spent a few minutes walking around the house and left, barely doing anything. The case was handled so poorly, she said, that when one of the police officers who dealt with it testified in court more than a decade later, he admitted that he was embarrassed by how the investigation had been handled. "The police didn't do a thing," Polk said. "I was thinking to myself, Shame on them, shame on the entire department."

After the police left, Polk also went to a Detroit hospital to have a rape kit compiled and to the police station to fill out a formal report. For months, she persistently followed up with the department about the progress of her case, but after repeated silence, she said, "I just gave up, and I wanted to let it go."

Then, on Feb. 3, 2011, almost 14 years to the day after the attack, Polk finally heard from the prosecutor's office. They said they knew who had raped her and wanted to know if she wanted to move forward with charging him. "For 14 years, I'm moving around knowing this person — monster, I should say — is out there and law enforcement never did anything," Polk said. She eventually went ahead with the prosecution, and now her attacker is serving a 28-year sentence. But, she said, "They just left me on a shelf for all these years and nobody gave a damn."

Polk was not alone. Her kit on the shelf was just one of 11,304 in Detroit's backlog of untested rape kits.

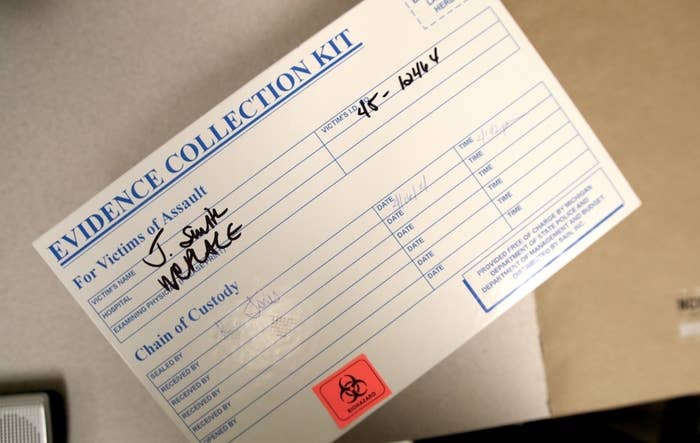

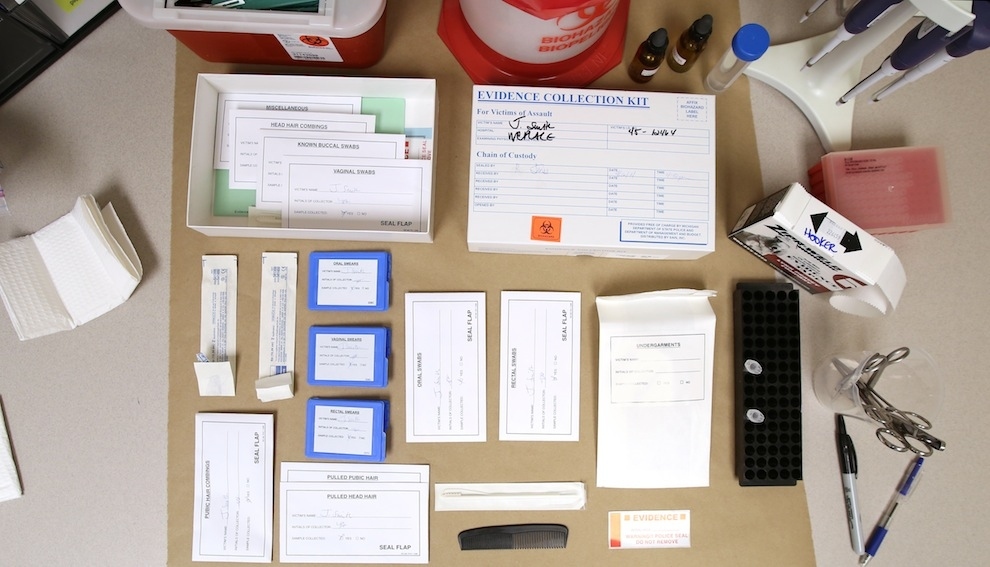

A rape kit itself is about the size of a lunchbox. The box is designed to store evidence in paper and keep the contents dry, which is the best way to preserve DNA. And while some of the backlogged kits are from 1989, as long as they haven't been submerged in water, a lab can still pull DNA decades later; the kits don't have an expiration date. They're filled with tiny envelopes that contain swabs and smears for each body part that has been touched during the assault, as well as hair and a comb used to collect the hair, and an envelope for undergarments. When a kit is collected, everything that may have been touched is swabbed for DNA. The lips, breasts, and vaginal areas are the most common places to collect DNA. The kit is as full or as empty as the victim wishes.

Five years after being appointed Wayne County prosecutor, Kym Worthy had a big project land on her desk. In August 2009, then-assistant prosecutor Rob Spada went to a Detroit Police Department overflow warehouse, looking for a particular piece of evidence for a case he was prosecuting. As he began wandering around the building, he found something unusual: boxes upon boxes stacked on top of one another at the back of the third floor. No one knew what was in them, or how long they'd been there. Later that day, Spada brought Worthy back down to the warehouse. What they found was a shocking number of rape kits — 11,304 they would later discover — that had been, allegedly unbeknownst to any department in the city, stored away.

"Literally and figuratively, we were blowing dust off these kits," Worthy said. Worthy went home that night and started researching. "I just googled '10,000 rape kits' and I was shocked because I didn't realize at the time there was a national problem. Everywhere popped up across this country, where they had backlogged or even worse — which is our case — untested. These cases were ignored and just pushed aside."

On a blustery cold day in February, Worthy is at her office in the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice in downtown Detroit. The building, dated and chipped around the edges, fits in perfectly with its city. Worthy, dressed in a suit with her hair slicked back into a tight bun, speaks quickly, as if someone might cut her off if the words don't roll off her tongue quickly enough. It makes sense, since so many in the county have tried to silence her, but the strong voice she has mastered gives her an opportunity to tell the astonishing story of the hand she was dealt in the prosecutor's chair of a troubled county.

The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that there are currently 400,000 untested rape kits across the country, and Detroit's backlog is the second largest federal authorities are aware of, having just recently been surpassed by Memphis. (Experts, however, say that it's possible that other cities have similar or even larger backlogs that have slipped through the cracks.)

Worthy immediately began a still-ongoing battle to open, test, and prosecute the backlog of cases, along the way becoming an outspoken advocate for taking sexual assault seriously in a city that has many crimes to combat. Worthy began calling the Detroit Police Department to get answers, and said she was told an internal investigation would be conducted to figure out who was responsible for ignoring so much evidence.

But Worthy wasn't going to wait around. In her mind, enough time had already been wasted and lingering would be a greater injustice to those tens of thousands of victims.

"They were not in order, they were not packaged the same, they were just all over," Worthy said, describing the condition of the neglected evidence. "One of the first things we had to do was build a database and figure out what we had." Since nothing in the rape kits indicated they were attached to a police report and nothing in police reports indicated they were attached to a rape kit number, this was a significant undertaking.

With a grant from the National Institute of Justice, Worthy and her team, along with volunteers, took all the information they could off each kit: victim's name, address, where the rape occurred, the date of the attack, etc., and created a database. Then they hunted for any police report that would match the data.

As she and her team dug through police reports, Worthy said she also noticed a pattern of how police officers treated victims. They found testimonies, she said, stating that officers had made comments like, "This victim is a ho. I don't believe anything she says." The DPD said it had no comment about victim treatment.

"They felt free to write these very degrading things about rape victims in their file in black and white," Worthy said. "And we were amazed that we saw this type of vitriol." Worthy vowed to not only open and prosecute all of the kits in the backlog, but to also look at the way victims were treated from the minute they came into the system and how that treatment could be improved.

Worthy and her team first dived into the database with a grant-funded initiative called Project 400, which tested a random sampling of the kits to gain a better understanding of the scope of the problem: how many offenders were still alive, how many victims were still alive, and what kind of cases they had (the number of stranger rapes versus victims who knew their attackers).

The prosecutor's office soon realized it was getting hits off these kits, and reached out to the Joyful Heart Foundation, an organization founded by Law & Order: SVU actress Mariska Hargitay to work with sexual assault victims, to be its national partner. With the NIJ grant, Joyful Heart's Vice President of Policy and Advocacy Sarah Tofte traveled to Detroit dozens of times over two and a half years to help create a task force, working in collaboration with the mayor, police, victim services, and crime lab to learn about victim notification, best practices, trauma and how it affects someone over the years, and what evokes certain behaviors. This research helped the team build a process for testing the kits and notifying victims.

Tofte also had experience raising money. In a city that had no funds to give — to this day, the city has not given a dime to the project — the task force had to utilize other resources, like foundations, grants, and private funding. Due to the severe budget constraints, Worthy said her office made a decision at the beginning of this initiative to not contact a victim until it could begin an investigation, which could be a year or longer after a kit was tested.

Because of the onslaught of work, newer rape cases are also suffering. Since 2009, when the backlog was discovered, 4,834 sexual assaults have been reported. Through the NIJ, the prosecutor's office has established one set of prosecutors who specialize in prosecuting those new sexual assault cases, and one set to handle the cold cases. "We're not doing it effectively right now because we don't have the resources," Worthy admitted. "I'm down almost one-half of my staff than I was two years ago because of the budget problems we're having in the county."

For decades, Detroit has struggled with riots, high crime rates, rapid population decreases, and the downfall and bailout of the auto industry. And since 2000, the city has dealt with a corrupt mayor (whom Worthy put behind bars), 1 in every 3 residents living below the poverty line, and the consequences of half of property owners being unable to pay their taxes. Detroit declared bankruptcy on July 18, 2013, but because the backlog wasn't receiving any funds from the county before the bankruptcy anyway, its progress wasn't derailed by the announcement. The bankruptcy filing has, however, further strained the prosecutor's office and general resources.

"Our victims are receiving an even greater injustice because now that we know about the rape kits, we can't even investigate and prosecute because we don't have the staff, which is unconscionable," Worthy said. "I don't know how anyone in their right mind that can live with themselves can allow this to happen, and I'm talking about the funding source."

But it's not just financial issues in Wayne County that are standing in Worthy's way. She detailed a deficit elimination plan that had been recently placed on her desk from Wayne County CEO Bob Ficano's office calling work on non-grant-funded sexual assault kit investigations and prosecutions "low priority," and saying that the work "should be discontinued." The letter was distributed Feb. 11.

On March 13, the CEO's office released another letter redacting the sentence and stating the comments about sexual assault were "based on an early draft" and were "inadvertently and mistakenly included." Questions as to why the comments were included in any drafts and why it took more than a month to issue a redaction were not answered by the CEO's office.

"We're a mandated office and last time I checked sexual assault was a crime. Their attitude is 'forget about those victims,' and it's pathetic." Worthy said. "So sexual assault is a low-priority crime to the CEO we have here in Wayne County. Those are the issues we face every day."

Despite the setbacks, Tofte said she was amazed by the work being done in Detroit. "In my professional experience it's been astounding to see in a city that has gone bankrupt that it would be the last place to do rape kit reform or establish a model, and yet that's exactly what Detroit has done," Tofte said. "I've worked with other cities that have many more resources that have been pulling teeth to get reform and Detroit is the total opposite."

There are two major problems with a backlog. The first, as Worthy put it, is that the system "discriminates our victims based on what year they were violated." The second is that the longer a rape kit sits around, the more susceptible it becomes to damage. And the most effective way to prosecute someone in a sexual assault case is with a rape kit, because that is where DNA is stored.

At the Michigan State Police Forensics Lab in Northville, Mich., variations of kits are constantly coming in. While a consistent process recently has been implemented so that all kits coming to the lab are complete from a court's perspective, that was not the case with kits more than a couple years old. For example, the lab has received kits with only one or two items collected when eight to 12 are really needed: with hair sample but without the comb (both should be placed in the kit before it's sealed); with the kit not sealed properly or at all; or with the DNA washed away (for instance, by showering or going to the bathroom before collection). The lab will try to pull DNA from every kit, but these types of situations make it much harder.

Billie Hooker, a forensic scientist at the lab, unpacked a rape kit with BuzzFeed. When evidence first comes into the lab, she explained, it's screened for bodily fluids. The lab looks for evidence that connects with an allegation from a victim. For instance, if the victim alleges that his or her arm was licked, the lab looks for saliva on a skin swab. A report is written up after the screening stage stating what was detected. Then DNA processing occurs, which is a process where chemicals are added to tubes filled with the DNA that was pulled during the screening. They extract, or open, the cells in order to pull the DNA out. Then they have to determine a numerical value of how much DNA is in the sample, a process referred to as quantifying, which the lab will use to know how much they need to amplify. Basically, they want to make millions of copies of these regions that are specific to the process. The FBI sets 13 regions, and you need all of those 13. A certain amount of DNA is needed in order to successfully quantify, but, even if there isn't enough, the lab will still try it. And that sample will, ideally, produce a profile. The profile gets cross-referenced with the CODIS system, a police log of DNA, in hopes of matching the DNA to a suspect.

One of the reasons the backlog has taken so long to tackle is the price: Typically it costs between $1,500 and $2,500 to test a kit. The high cost is the result of the highly trained professionals needed to work on the kit, the expensive equipment, and the constant replacement of supplies to keep the tools and tubes DNA-free. On top of this, all of the work has to be reviewed by three analysts before it leaves the lab.

The prosecutor's office, however, has recently been able to cut the price of testing a backlogged kit almost in half by working out an agreement with the labs due to the volume of kits coming in. According to the Detroit Police Department, approximately 2,500 of the 11,304 kits have already been tested, and 7,400 kits were sent out to labs in December 2013 and January 2014. Of the remaining 1,100 kits, "many were either tested in the first waves of testing or there are reasons not to test the kits (i.e., the case has been adjudicated, guilty pleas, etc.)."

Wayne County Safe, a nonprofit formed in 2006, is the only program in the county that collects rape kits, deals with crisis intervention, and works with survivors after an assault. It's open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and everything is free. And about 70% of its cases come from the city of Detroit.

In Wayne County, kits are no longer collected by hospital staff. Instead, when someone goes into a hospital and states they've been attacked, the hospital contacts WCS, who works with the patient to determine where they want to have the services done.

Eight years ago, kits were mainly collected by people who weren't well trained or didn't know what to look for, a problem that has been improved by WCS centralizing that process. Police, meanwhile, dealt with staffing issues and officers who made their own judgment calls about believing a victim, according to WCS executive director Kim Hurst. WCS now works with police officers to diminish prejudice and victim blaming.

"This can't happen again," Hurst said. "We can't have kits sitting around because an officer didn't believe a victim." Victims are now automatically given WSC's contact information when an assault is reported, and the organization remains involved in the process at every step. WCS experts are trained and specialize in handling sexual assaults, and supporting victims along the way. They frequently join victims when they meet with the prosecutor or in court and provide counseling.

Another issue for victims is physically getting to the help they need. Detroit's public transit system is one of the worst in the country; buses can sometimes take hours to come. In some cases, Hurst said, victims have even been attacked at bus stops. The organization pays for victims to be taken to and from their offices, with cab drivers who have been prescreened and don't have a criminal record.

But just like with the prosecutor's office, none of the funds for these services come from the city.

"Going to the city, there wasn't a lot of interest or support, in 2004, 2005," Hurst said. However, in the midst of severe cuts due to the Chapter 11 filing, Hurst said she is actually glad the city never backed them. "It has worked out very well for us. This bankruptcy hasn't affected our flow financially."

WCS does have state and federal grant funding, as well as private donations. And just like Worthy, Hurst knows that if the city had any resources to devote to her organization, they would be doing a lot more work. She detailed a plan to hire additional staff and advocates, as well as to establish a more comprehensive rape crisis treatment center.

To date, almost 100 serial rapists have been prosecuted from the backlogged kits, Worthy said. The attackers have been located in 13 states across the country, the furthest being in Alaska. There is no longer a statute of limitations in Michigan for criminal sexual conduct in the first degree, so while there are cases from the 1990s in the backlog that had already outrun their statute of limitations, the prosecutor's office can use evidence from newer cases to argue the older ones. And if DNA is found, the statute will be tolled — essentially legally suspended. Worthy's office is also working to implement a system that will allow all victims to be able to see exactly where their kit is, from police headquarters to the lab to the courts. "If UPS can track a package, a rape victim should be able to track their kit," Worthy said.

"It's an incredible story and should inspire other cities," Tofte said. "If Detroit can do this, anybody can do this."