The Home Office will face a judicial review this year over long delays in making asylum decisions for unaccompanied children, BuzzFeed News can reveal.

More than 1,600 children who arrived alone in Britain to seek asylum had been waiting more than a year for a decision last August, new figures show.

Asylum cases are supposed to be decided within six months, and those involving unaccompanied children are meant to be prioritised because of their vulnerabilities.

But Freedom of Information requests by lawyers on the case reveal:

For unaccompanied children under 14, it took an average of 627 days to hear a decision on their asylum case last year.

In August 2018, there were 3,457 unaccompanied children seeking asylum in the UK waiting for a decision on their case.

64% were waiting longer than six months, and of those, 47% were waiting more than a year.

Despite the priority that is supposed to be given to children claiming asylum alone, other, less urgent applications are routinely decided much more quickly. The average time for a decision in other asylum cases was 347 days in 2018.

Lawyers working with children in these cases say the impact of these delays on young people’s mental health, wellbeing, and education is profound.

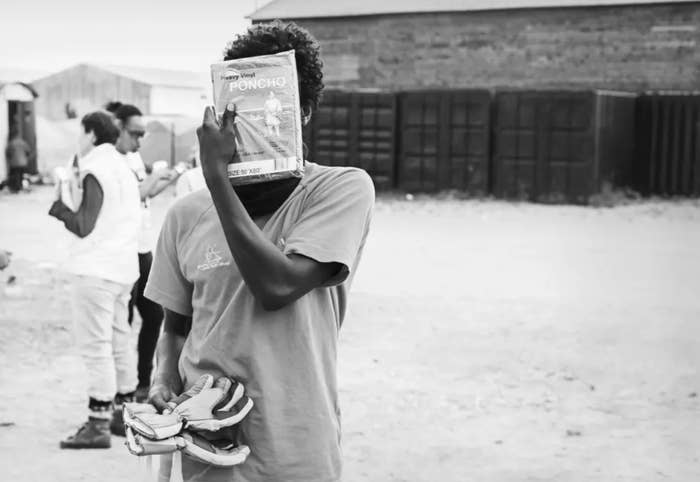

The test case centres around a young man who was 17 when he arrived in Britain to seek asylum from his home in northeast Africa. He was one of 750 children brought to the UK directly from Calais, France, by the Home Office as part of an operation to clear the camp there in 2016.

The young man, known only as MK to protect his identity, is now 20 and waited almost two years for a decision. He was only granted asylum at the end of last year after legal proceedings began against the Home Office.

The Home Office has conceded that the delay in his case was unlawful.

MK told BuzzFeed News the long wait had put a huge strain on him and made it difficult to concentrate at college while his future was uncertain. “Always in my head was, Will I get asylum? Will I get asylum? I couldn’t think about anything else,” he said.

Repeated reports by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration have criticised the Home Office for significant delays in making asylum decisions for unaccompanied children. In an inspection report in March 2018, the Home Office was told it needed to revisit all of the recommendations made in 2013 and “make improvements that stick”.

Daniel Carey, a solicitor at Deighton Pierce Glynn who is bringing the case, said: “It is really significant that the Home Office has now accepted that the long delays our client experienced were unlawful. But there are thousands more children affected by such delays and their cases have still not been resolved.

“Having seen many of these cases now, it is clear that the prolonged uncertainty can have a really debilitating effect on what are already very vulnerable young people at a formative time of life. It is promising that the Court will now look at the systemic causes of all this at a further hearing.”

Similar attempts to use individual cases to judicially review the Home Office have resulted in the fast-tracking of a decision in the case so that it can then be argued it is academic. This time, the judicial review was granted despite the expedited decision because lawyers pre-argued in their submission that the case should be allowed to continue because it was indicative of a systemic problem.

For MK, and hundreds of children and young people in the same situation, the long waits have destructive consequences.

In a witness statement written while he was still waiting for a decision, MK said: “The waiting is affecting me in every possible way. Not knowing about my future is impossible, the uncertainty is killing me.”

His 18th and 19th birthdays went by while waiting for an asylum decision, drastically reducing what help he was entitled to and meaning he had to be uprooted from the town in the southwest where he was living to a place miles away on the east coast where adult accommodation was available. He has not been able to continue his education despite being accepted onto a course.

Commenting on the move in his witness statement, MK said: “I was a smart student and I was happy studying. Now all my hope is shattered and I feel like I cannot absorb information in the way I used to. My condition is deteriorating day by day and I feel like I am considered an animal rather than a human being. I just eat one meal a day and try to sleep and that is it.”

He is lonely in the adult accommodation he was moved to and said many of those in neighbouring rooms have serious mental health problems and he has seen them self-harm.

In his statement, he said: “I do not have a social worker or an advice worker since it has been the Home Office’s responsibility to look after me. It feels like I have been abandoned. I was given some numbers if I needed any support or help. I have tried calling the numbers, but I am just put on hold and then my phone credit runs out.”

He added: “I feel like I have been failed. The Home Office brought me from Calais to this country and so I expected that there would be someone to take care of me emotionally and physically. This has not happened.”

Shadow home secretary Diane Abbott said: “It is shameful that the Government would treat already vulnerable asylum seekers in this way. To leave children feeling abandoned and without hope of a stable future, is yet another example of the Tories hostile environment.

“It is unacceptable that the Home Office is falling short of its own guidelines and is not prioritising these delays.”

Coram Children’s Legal Centre, the Refugee Council, the Law Centres Network, Asylum Aid, and the Migrant and Refugee Children’s Legal Unit at Islington Law Centre all provided evidence for the case of how the young people they worked with were affected, revealing the scale of the problem.

Rosalind Compton, a solicitor and outreach worker at Coram Children’s Legal Centre who provided evidence for the case, told BuzzFeed News the impact of months — and years — of indecision is profound.

“Children’s perception of time is different,” she said. “When you’re 40, a year is a long time but it’s a much smaller percentage of your life. When you’re 16 and you’re going through the critical teenage phase, especially in relation to education and forming friends and social links, you have a less clear identity, having that uncertainty for a year can be really damaging.”

She added: “They become incredibly anxious about waiting for a decision. I’m constantly seeing children saying ‘I can’t concentrate at college, I can’t sleep because I just want a decision’.”

Compton believes that not having an asylum decision also impacts the level of support unaccompanied children get from local authorities.

She said: “I’ve seen they get treated slightly better by social services if they can see they have a valid leave to remain.

“I saw a young person a few months ago who was very distressed because he had medical issues that meant he had seizures sometimes and severe night terrors. He’s been sharing a room with a friend who had once called him an ambulance. The friend had been granted status and moved into different accommodation, and what he understood from the social worker was that his friend had been moved because people with leave were housed in one place and people without in another. There was a sense that accommodation was for people who were moving forwards and his was for people left behind.”

A Migrant Legal Project worker said in a witness statement that they had not experienced a single case of an unaccompanied child where a decision had been made on the claim within six months — and that most decisions were made after children turned 18. Out of 27 cases seen by the project since 2016, 23 involved delays of over a year, and 17 of these had experienced a delay of 18 months or more. The Home Office did not give reasons for the delays or respond to requests for expedition.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “We do not routinely comment on ongoing legal proceedings.”