KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI — “Stop the car!” a police officer yells in the video, pulling out his gun as a silver Audi minivan kicks it into reverse, swerving away from him. The officer runs after the car.

“Get out, get out, get out,” the officer says, his words blending together. He aims his gun with one hand at the Black man driving and holds his radio with the other.

A fast-moving situation. An officer with a drawn weapon. A Black man suspected of a crime. Bystanders screaming at the police that the man behind the wheel has a mental condition. And a video broadcast on social media. Time and time again the world has seen these videos end in tragedy.

But no one is shot in this video. At the tensest moment, a soundtrack amps up music that would fit in a Fast & Furious trailer. Without incident, the officer gets the driver out of the car and takes him to a hospital for mental health treatment.

This video, which was uploaded in July 2020 and has more than 87,000 views, is one of hundreds the Miami Police Department has put out since it started vlogging in 2015 (the most popular has 3.4 million views). Miami is just an early adopter of a renewed tactic. Now, police departments across the nation are producing slick videos, pushing a “good cop” image after years of outrage over shootings, many captured on video and published to social media, and the resulting protests demanding accountability. The New York Police Department has posted over 800 videos to its channel, including web series called Beyond the Badge and Neighborhood Policing. The Los Angeles Police Department regularly posts bodycam and security footage, sometimes cutting it together with a moving score, like this video of an officer providing first aid to a man injured during riots after an LA Lakers championship game.

The videos continue the tradition, popularized by shows like Cops and Live PD, of glorifying police work via highly edited, suspenseful, “documentary”-style entertainment. But these are coming from the departments themselves, with police employees editing and uploading the clips right to YouTube. A new form of “copaganda,” as activists refer to it. There has been a boom in these shows and channels over the past 19 months, after both Cops and Live PD — criticized for years for glorifying police work and perpetuating racial stereotypes — were canceled amid the summer 2020 protests. (Cops is now making a return on Fox Nation.)

Current and former spokespeople for five different police departments said these videos help with “public education,” “community outreach,” recruiting, and morale.

But most critically some officials say they are made to counteract the dominant online presence of the police accountability and reform movements of the past eight years.

When video of George Floyd being choked to death started circulating around the world, “every police department that was watching that in the country went. Oh, F.U.C.K. is this going to hit us?” said Lauri Stevens, the founder of SMILE, an annual conference, awards, and training outfit for law enforcement social media use.

“And it did, and they knew it. They knew it from the minute it happened, it’s going to come down on us.”

The reaction among departments was an age-old tactic strengthened by new technology: Drive the narrative you want to get out.

Still, some of the officers who make the videos are reckoning with their involvement in them. Take Officer Malcolm Whitelaw of the Kansas City Police Department, who was at the vanguard of his department’s video strategy. He’s also grappling with being the public face of the very system that’s caused him fear in the past.

I followed Whitelaw for a few days this summer as he made and edited a video about applying to become a police officer. The goal was to boost recruitment.

We walked around police communications and media headquarters in Kansas City, the department recruitment office, and the police academy as he filmed in selfie mode, explaining how to apply and what someone should expect if they are accepted into the academy.

“People tell me my videos look like Live PD, but I don’t really think so,” Whitelaw said when the camera stopped rolling. “I’m still kind of figuring out my style.”

Whitelaw, who is Black, is a 29-year-old former marketing student who has been on the force for six years. He’s hulking and friendly, with a squinty smile.

Whitelaw loves working as a police officer, but, he told me repeatedly, he doesn’t consider it his identity the way he believes many of his colleagues do. It’s just a job, he said. At the end of the day, the badge comes off. Then he’s just Malcolm.

He was a patrol officer before he started making videos for the department at the beginning of 2021. The videos were his idea, inspired in part, though maybe subconsciously, he conceded, by his experience patrolling last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests.

“As I was standing there, there were some girls, like, yelling at me, and I kind of got confused because this is a young white girl telling me that I don’t understand what it means to be Black,” Whitelaw said, sitting at a conference table with his two white bosses, who were nodding along. “And I’m like, I have more experience in this field than you.”

Later, during a break from shooting a video in the recruitment office, away from his colleagues, we discussed the issue further.

“I’m a police officer, and I’m also Black. No confusion there. And so my experience as a police officer is very different sometimes than those that don’t share my skin complexion. Because, well, where do we police? Right? We police in areas with people that look like me,” Whitelaw said, his voice lowering an octave.

For Whitelaw, and for the Black protesters he was patrolling, dealing with police hostility and brutality had been a reality their whole lives.

When Whitelaw was a sophomore in high school, living just outside of Kansas City, he said, he was walking home from school when suddenly an officer pulled up and, gun out, stopped him. Whitelaw didn’t know what was happening and the officer didn’t explain, he said, but kept telling him to stay where he was. Soon, several more cops pulled up around him. They held him there until they figured out he wasn’t the guy they were looking for.

“I matched the description,” Whitelaw added. He was scared, and his mother was furious.

“Growing up, I didn’t like the police, I wouldn’t talk to the police,” Whitelaw said. “My head was hardwired like that. That was a huge hurdle to get over because I had all the same thoughts as the people that don’t like the police. You know, I had started working for a department” — he later clarified his encounter with police was with a nearby department — “that pulled me over at gunpoint.”

Whitelaw said he regularly encounters people who still think that way, who see him as a traitor for being a Black police officer. Because of that, he said, he finds himself having to “exist in that place as a human being, not so much getting caught up in my skin color.”

“There’s people who look at me and they hate me that much more because I’m Black. ‘How dare you?’ You know, like, ‘How dare you be a police, you know what they’ve done to us.’ That’s what people are thinking,” Whitelaw said.

“It’s sometimes so disheartening because it’s like, I’m the best person to have right here, you know. Because I’m not looking at you because of who you — because of this situation,” he stumbled over his words. “I’m looking beyond that. We can handle our business, and I’m gonna treat you as a person you want to talk to with respect.”

He hopes to bring some of this understanding into his videos. Whitelaw has been obsessed with YouTube since he was a teen, fantasizing about creating his own videos and becoming a sensation on the platform. After watching Miami’s police vlogs religiously, he decided that his department should do something similar.

The chief approved it, and Whitelaw’s been on special assignment in the media unit since the beginning of 2021. When I was with him in August, he said that so far the office had given him almost free rein. He taught himself video editing and about equipment online and invested a significant chunk of his own money (though he wouldn’t say how much) in cameras and lenses. The department put out its first vlog in March.

After the first couple of YouTube videos, the KCPD YouTube channel had a 1,000% increase in viewership — this is according to Whitelaw — and saw 1,400 new subscribers in the first few weeks. Things have steadied since then. As of mid-January, the KCPD had published its ninth video and had nearly 7,000 subscribers. Whitelaw also recently launched a KCPD TikTok page, hoping to reach a younger, wider audience.

Right after the channel launched, he started getting inundated with requests from officers in other departments to be featured on the videos. Pro-police commenters leave positive feedback and aspiring officers use the forum to ask Whitelaw questions in the comments about how to become a cop. He has even started getting recognized in public, he said.

Whitelaw’s hope for these videos is that they show the benefits of community policing, not just to the public but to current and future officers. Officers, with burnout, social pressures, and a high-intensity work environment, sometimes need a reminder of why they got into the force, Whitelaw said.

“As police officers, a lot of times we have to be so rigid, right?” Whitelaw said. “We’re dealing with, you know, traumatic events, and sometimes when you’re out there, you kind of forget to be a person. So that’s what I try to get people to feel and remind them: You are a person.”

He added that it doesn’t hurt that the videos help boost morale, by making officers feel badass, “seeing themselves with cool music and, you know, different shooting angles, and seeing how much fun people are having.”

While I was with the KCPD, Whitelaw made a video about the testing process for applicants to get into the police academy. It came after the chief requested that the KCPD up its recruiting game.

The plan was to follow the latest group of applicants as they took the exams. Whitelaw gave his followers a tour of the academy’s training facilities. He walked backward along an indoor running track, filming in selfie mode and breathing hard as he talked through his KCPD-branded mask.

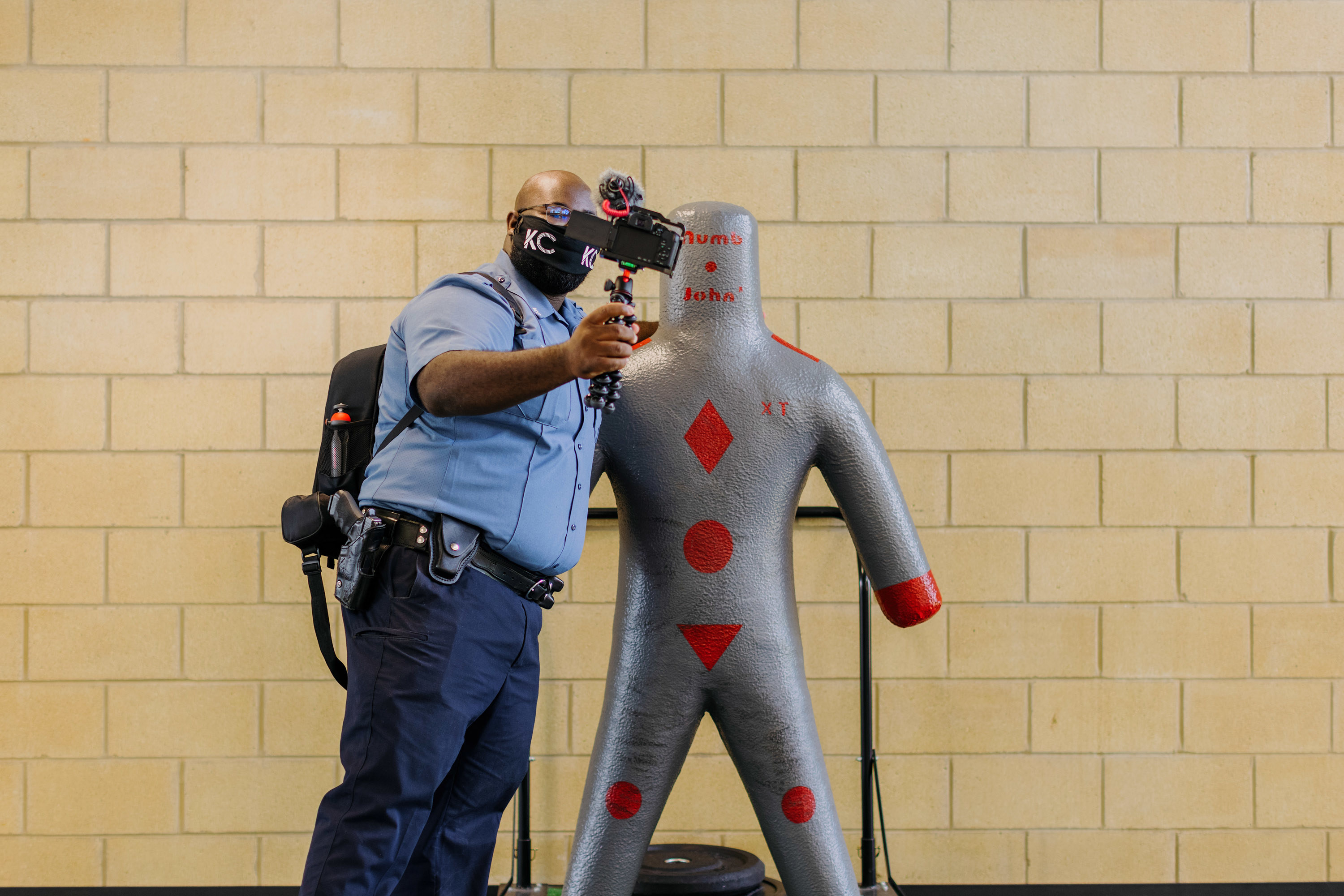

“Us police officers, we try to de-escalate using the best de-escalation tactics, which you will learn at the police academy,” Whitelaw said, walking up to a punching bag. “But, you know, life is very unpredictable.” He lightly punched it three times, then walked over to a life-size, silver, rubber figure with red shapes marking its chest, stomach, crotch, and knees. This dummy, named “Numb John,” is for baton training, he explained.

Next, we walked downstairs, past large cardboard printouts of a white, bald man with a goatee in a fighting position. He was covered in hundreds of tiny holes on his back, stomach, and crotch (stun gun practice, Whitelaw remarked). Then we entered the hand-to-hand combat training room. The room looked like a karate dōjō. On one wall hung a “thin blue line” American flag, and on another hung two black-and-white pictures of officers putting people in, apparently, chokeholds. Between them was a banner reading “‘Come to the Party People’ - Jim Lindell.”

(Lindell invented a controversial alternative to chokeholds, which the KCPD has argued is less dangerous despite repeated calls from local organizers to ban the use of the restraint, though the department has refused.)

We entered the exam room. Most of the 22 people applying to join the police academy had already taken their seats. The majority were white and male.

The officers allowed me to take a quick poll of the applicants. I asked if anyone had watched Whitelaw’s videos for the KCPD, and four people raised their hands. I asked if anyone regularly watched YouTube videos from other police departments or about policing, and eight of the applicants raised their hands — all men, mostly white.

“I spend a lot of time on YouTube watching videos about what it’s like” to be a police officer, Jay Humfeld, 42, told me. He’d been thinking about becoming a cop for a while, but watching Whitelaw’s videos — as well as Live PD and other police content fed to him by YouTube and Facebook’s algorithms — helped push him to actually apply.

Once YouTube’s algorithm learns you’re interested in this genre, it’ll take you from officers in Houston using a heat-tech drone to find a fugitive hiding in a sewer system to a montage of police dogs in the Kansas City K-9 unit opening car doors with their snouts to a trans officer in Seattle standing in front of a skyline and telling her story. They’re largely a behind-the-scenes look at the job — the action, glamor, humor, and camaraderie. But they all share a message: We are the good cops.

Two of the other applicants, a 28-year-old named Juan and a 22-year-old who asked me not to use his name, both of whom have military backgrounds, said they’d also watched Live PD and Cops, as well as videos from the KCPD and other police departments. They said YouTube fed them both kinds of videos interchangeably. The 22-year-old said he used to watch the Miami Police Department videos and thought they were “kinda cool.”

“Police departments are making videos about what they do every day, and the different kinds of police officers like SWAT and vice, just everybody, it’s cool to learn about,” he said. He added that the main reason he was applying was that his uncle had just retired from the KCPD the week before.

Juan estimated that he watches about 30 to 40 minutes of these videos a week unless he gets in a “scroll hole” and loses track of time. Entering the police force is a common career move for people with a military background, he said, but the videos also helped him understand what police work was really like, they made him feel like he could actually do the job.

“That and also, I feel like there’s this negative connotation to police work, and the way people see it,” Juan added. “I just want to be the best person that I could, and help the community.”

In posting dozens, or hundreds, of hours of content on a regular schedule, police departments are essentially turning themselves into multimedia publishing platforms. They use Twitter to break the news, Facebook Live to give press conferences, Nextdoor to track and respond to neighborhood issues, Instagram to defuse tension with positive counterprogramming, TikTok to reach Gen Z, and long YouTube videos to provide ongoing entertainment and “education.”

Nick Perez, a current police officer who started and starred in the hyper-popular Miami Police Department YouTube channel, told me that when his unit began the channel, they were seeing a lot of outrage over police violence online.

“Back in 2015. It was a very anti-police atmosphere that was going around social media and there was no real pro-police side, nobody speaking on behalf of the police departments,” Perez said. The result, he said, was, “OK now here’s the police side, but we were doing it to reach out to our community as the Miami police department. However, we kind of took on the role of the pro-police content that was coming out.”

Other police agencies caught on, he said, and suddenly, “with the idea of reaching our community, we kind of reached the world.”

“The news was running stories about police whatever, what was happening with police in a negative light, but all we were doing was showing what we were doing,” Perez said later. “Which in turn made [people say], ‘let’s share their positive story.’ [There was] a lot of anti-police rhetoric, and we were the positive story coming out around that time.”

Perez’s YouTube videos have also significantly boosted recruitment for the department, he told me, highlighting a recruitment video they recently posted that resulted, he said, in 1,000 new job applications in 12 hours.

The massive protests that erupted after police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, were the catalyst for not just Black Lives Matter but for police departments to realize they needed to embrace these new methods if they wanted to be heard, Stevens, the founder of SMILE, said.

“Ferguson was a huge, huge, huge event, Charlottesville was huge, Baltimore, all of them were big in the whole social media policing [uptick]. But Ferguson was a real peak in police social media,” said Stevens.

“The Ferguson Police Department were doing zero with social media when the whole ‘Hands Up, Don’t Shoot’ situation went down,” Stevens said. “Now they’re very much in support of using social media and understand that they have to use social media, because they get how social media was their undoing that day.”

One former police officer — who asked not to be named so as not to jeopardize his new career — worked in police media outreach in a liberal city for years, but left the force in part due to the systematic problems exposed by the Black Lives Matter movement. He said that he faced a lot of debates in his department over how to use social media, particularly video platforms.

“OK, so I’ve learned more about this wonderful human driving a patrol car and responding to tough calls,” he said. “But I’ve got a problem with the person who stopped me last week and was very dismissive and rude, or called my friend a racial slur, or refused to give me their name and badge number.”

If there is no clear way to file a complaint about that other person or to successfully hold them accountable — which there very often is not — then showing examples of positive policing without any means of accountability is creating a false narrative, he said.

“It’s a really fine line if you’re only doing one and not doing the other,” the former officer said. “Then that — that borders on propaganda.”

Kansas City illustrates the problem. In order to file a complaint against a KCPD officer, citizens have to contact the Office of Community Complaints, “a non-police, civilian oversight agency.” However, the site makes clear, if the office deems the complaint worthy of an investigation, it hands that complaint over to the department’s Internal Affairs Unit. According to KCPD’s Office of Community Complaints, of 1,059 complaints in Kansas City between 2016 and 2019 against police officers, 246 investigations were completed, and only around 12% ruled in favor of civilians, the OCC said in a statement. The Police Scorecard, a public database tracking police accountability nationwide, found that of the 132 use-of-force complaints during that time, 0% ruled in favor of civilians. KCPD’s OCC said in a statement that “most of the force investigations either do not present enough information for the OCC to make a determination or the evidence proves conclusively that there was no violation of policy or procedure,” and added that in cases where the office does not rule in favor of the complainant, they may still take “corrective action” like training or policy reviews.

The KCPD has, though, recently been held accountable in the court system. In November, an officer was found guilty of killing Cameron Lamb in his home during an erratic driving investigation. The trial was reportedly the first for a KCPD officer accused of killing someone in the line of duty since 1942.

The videos also raise other questions of accountability. Robin Andersen, a professor of media studies at Fordham University who has studied media treatment of police and the military for decades, observed that the officers in these videos often deal with people with mental illnesses, sending them off to hospitals and emergency rooms instead of arresting them.

Replacing police with mental health professionals has been one of the major demands of police reform activists. And since last summer’s protests, several cities around the country have attempted to oblige, rolling out pilot programs that send specialists instead of police to behavioral health calls. According to a Washington Post database of fatal shootings by police, almost a quarter of the people shot and killed by police since 2015 have mental illnesses.

The results from the first three months of New York’s version of this program were promising, and New York expanded the program in November. More people called for and received help than they do from 911 calls, New York 1 reported, and fewer people were transported to the hospital (which often does very little for a patient and leaves them with exorbitant medical debt). In June, the KCPD started requiring all of its officers to take a 16-hour “Intro to Crisis Intervention” course (though, KCPD noted, 55% of its officers have taken the full 40-hour course), and the department has one, five-person squad called the Crisis Intervention Team. It specifically responds to mental health calls but is composed of police officers. The department does not currently have plans to replace officers with civilian mental health specialists, KCPD said.

“It is so clear, the reason these videos exist is to block and attempt to affect the public’s demand for police reform,” Andersen said. “They’re saying, ‘We don’t really need this. We are really nice guys already doing really good work and helping people.’ But we know that is, in reality, not the case.”

In a statement responding to Andersen’s analysis, KCPD’s public information officer, Jake Becchina, disagreed. “Our department is constantly striving to be a better version of itself. We don’t always get it right, but we try to make improvements,” Becchina wrote. “We would never say that we are perfect and reform/improvements/change (however you would like to say it) are not needed. As such providing videos to try to prove that reform isn’t needed would be counterproductive to our mission.”

Outside of the Kansas City Police headquarters, statues memorializing fallen officers were wrapped in cellophane since the protests. All year, people protesting police brutality had been graffitiing them with “BLM” and “No Justice No Peace,” so the city covered them up. One statue, not wrapped, was a metal sculpture of a man plugging his own ears, his shoe in his mouth, and his tie around his eyes. It sat directly in front of one of the entrances to the building. The sign next to it read “Communications.”

Inside, cubicles are covered in children’s drawings, bobbleheads, plants, and family photos. An indoor putting mat stretches between the desks, leading to a conference table and a whiteboard with the words “Twitter is not real life” written above plans for the team’s social media strategy.

Pro-police paraphernalia faces Whitelaw’s desk from almost every direction: a pegboard sign reading “Blue Lives Matter KCPD,” the “thin blue line” flag on a large wooden police badge, a shelf designed like the American flag holding police badges in each stripe. Whitelaw’s boss, Jake Becchina, wears a "thin blue line" dog tag with a prayer on the back around his neck.

“I don’t have any Blue Lives Matter stuff,” he said flatly when I asked him about it when we were away from the office. “It ain’t my cup of tea. And that’s all I’m gonna say about that.”

The day after shooting the video at the academy, Whitelaw sat in his cubicle, preparing to edit the new footage and to add captions and a soundtrack. He wanted to get it out as soon as he could, so the next academy class would have even more applicants. His colleagues were sitting at the conference table, explaining to the least online among them what an influencer was. One of them called Whitelaw an influencer, and he chuckled.

“What if you are, though?” I asked, sitting behind him. “We’ve had a lot of discussions about how you don’t consider this job your identity. But if these videos get more popular, and you’re kind of the face of the department, how do you feel you’re going to reconcile those things?”

“I’ve kind of, like, feathered the idea, if that makes any sense,” he said. “Because outside of this world, I’m just me. I wouldn’t want to, you know, confuse the two. I love the department. I love the community. But like, am I going to be running around being, like, Officer Whitelaw everywhere I go?”

I pointed out that he said people were already starting to recognize him on the street.

“You’re asking me something that I haven’t necessarily thought about,” he said. “So your question is, what does it look like when I’m out there in the world, and I’m not just a random Black dude, even not in uniform, walking around in the streets? But now I am Officer Whitelaw from YouTube. That’s how people recognize me.”

He took a deep breath and thought about it more, talking through the question aloud until he came to a conclusion.

“If you have to be the face of something, at least it’s being the face for the right reasons, or good reasons, things that are positive,” he said, and started chuckling again.

“Because there will be a face of the department some other way, so it might as well be me.” ●