“You come back here, you take off your heels, and you put on your combat boots,” Denyse Gordon shouted as the contestants fastened the straps of golden stiletto heels, and zipped and unzipped garment bags. “You girls got it? Heels to combat boots, then back onstage, and show some leg.” Gordon smiled and lifted up her skirt, flashing her muscular calves.

Gordon, an Air Force reservist turned pageant director, stood in the middle of a room lit with fluorescent lights at the University of Nevada Concert Hall in Las Vegas, waiting for 25 military veterans to gather around her. It was hours before they would parade onstage in ball gowns, before they would be drilled on military history and participate in a “Push-up Princess” competition while a drill sergeant screamed commands, before they would find out who among them was the next Ms. Veteran America.

This wasn’t just any beauty pageant. Ms. Veteran America, now in its fourth year, was launched as a fundraising event for Final Salute, a nonprofit created to benefit the estimated 4,338 homeless female veterans in the U.S. — the fastest-growing segment of the homeless veteran population according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Judged by an all-female, all-veteran panel, the contest is more sisterhood than sabotage, the contestants striving to prove their resilience, grace, and poise. The winner receives $15,000 to be used on education, student loans, home purchase or repairs, or starting a business. She also becomes the official face of the contest and Final Salute, attending dozens of public speaking events, parades, morning talk shows, and next year's pageant.

Onstage, the women milled into a circle around Gordon. One contestant, Heather Worley, 30, a short, towheaded Army sergeant with youthful cheeks and a snub nose, leaned against a wall among discarded high heels. To her left stood Szu-Moy Toves, 40, a 20-year Air Force veteran and former bodybuilder with long black hair and a striking white smile. Kerri Turner, 32, an active-duty platoon trainer for the Washington National Guard and regimental operations officer, sat in front of the group, nervously clutching a large water bottle, her round eyes thick with mascara and fixed on Gordon. They all wore pageant sashes bearing “MVA 2015” over white T-shirts reading “Served Like A Girl.”

"The crown is not what it’s about."

“We so appreciate you girls’ hard work, dedication, and sisterhood over the past two days — over the past few months,” said Gordon, who won the title in 2012. “But you girls know, the crown is not what it’s about. The talent is not what it’s about—” her voice cracked. She paused, putting her hands on her hips and letting out a sharp sigh.

“Oh god, don’t start,” Toves said. The veterans began sniffling, pulling out tissues, and fanning their eyes to keep makeup from running. “I think we all just got a little bit of dust in our eyes,” another laughed.

Many of the women — contestants and judges alike — cried during the competition. Sometimes a song or monologue during the talent competition got to them. Other times their tears were aided by alcohol and the joy of being surrounded by fellow military women — a rare occurrence even before they'd left the armed services. Toward the end, some cried when they lost, and others, when they won.

“Military girls don’t get emotional,” Maj. Jaspen Boothe, a 15-year veteran and founder of the Ms. Veteran America competition, told BuzzFeed News. “That’s what we were always told. So it can’t be tears. It has to be dust.”

The fourth annual Ms. Veteran America competition took place over two days in and around Las Vegas. Sunset Station, the hotel-casino where the contestants stayed and the semifinals were held, smelled like decades of cigarette smoke and spilled cocktails treated with industrial-strength cleaner. Like in many other casinos in the area, the ceiling was made to look like a bright sky — but here the paint was peeling.

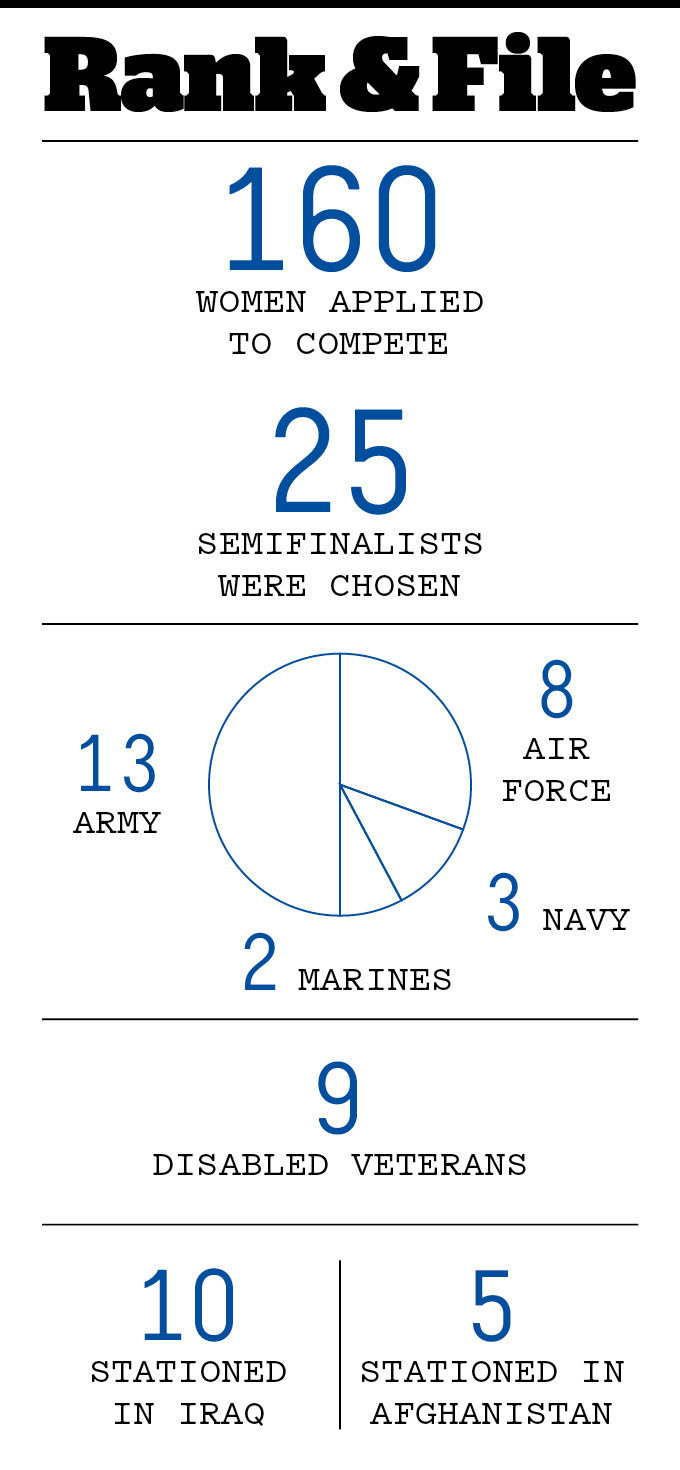

Though the semifinals and finals were held in October, the journey to Ms. Veteran America actually began months earlier. Over 150 women of different ages, races, upbringings, and military branches entered regional competitions over the summer, which took place in Virginia, Nevada, and over Skype. The panel of judges looked for applicants who were the most creative, eloquent, vivacious, and committed to helping their fellow women veterans.

Once chosen, the 25 finalists spent months soliciting donations for the charity, creating social media presences, and trying to get funding for their ball gowns, travel, and other expenses. Most came to Nevada on their own dime — no easy feat on veteran compensation and disability checks. Many had to find child care and take time off work, while others faced emergency surgeries, deaths of family and friends, PTSD flashes, and other catastrophes days before the main event.

“Preparing for this — getting donations, being on social media all the time — has basically been my life for the past few months,” Worley said, helping herself to the backstage snack spread. “My husband would sometimes get frustrated, saying, ‘I wish you had a little more time for me.’” But she needed to do this for herself.

At 8 a.m. the day of the semifinals, the 25 contestants — made up and stilettoed, large biceps bulging from cocktail dresses — squeezed into a waiting area for registration, meeting and greeting, then mostly waiting. They knew only 10 of them would move on to the next day’s finals, where they would compete in front of a live audience at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. They pored over binders, tapped their fingers, chatted in hushed tones, and checked their makeup using selfie mode on their phones. One woman fixed and refixed the harness of her service dog, a golden retriever named Grace.

They were waiting to be called one by one into the conference room to sit alone in front of a panel of five judges led by Command Sgt. Maj. Michele Jones, the first woman to reach that rank. There the judges asked each veteran about military history and current events, soliciting fact-based answers or personal opinions. The questions were “top secret” — a classification the women took very seriously — and reminded the contestants of the many nerve-racking, challenging tests they had to take as military trainees. An hour in, multiple women had emerged from the interview room sobbing.

“Right now is worst part of the whole competition,” Worley said between offering fellow contestants doughnuts. The sergeant is originally from Ohio but has spent the last seven years in Alabama, where she adopted a slight Southern twang. “It’s just that it’s all unknown that makes it so nerve-racking.”

“And also the sergeant major,” she said. “Talk about intimidating!”

“When a male veteran is homeless, his country failed him. When a female veteran is homeless, she failed her country.”

While the contestants waited, they swapped stories of first hearing about the competition — and reacting with disgust. “Great, just what girls want to be celebrated for after years of unrecognized military service — their appearance,” one contestant recalled. Another said she pictured women holding M16 rifles and parading around in bikinis and heels, waving at an audience of civilians. But as they learned more about the competition, they came to realize it was about charity, not bathing suits. More specifically, a charity for them.

Worley herself was homeless for much of her childhood. For years she lived in tents, motel rooms, or tiny apartments with her five-person family, working in fast-food restaurants with her mother long before she was the legal working age. At 17 she joined the military “without much thought,” she said. She was shipped off to South Korea.

Several other contestants became homeless after leaving the military, finding that the skills they'd honed since they were 18 were not applicable in the outside world. As they struggled, they felt overlooked by the VA and civilians alike.

“When a male veteran is homeless, his country failed him,” founder Boothe said. “When a female veteran is homeless, she failed her country.”

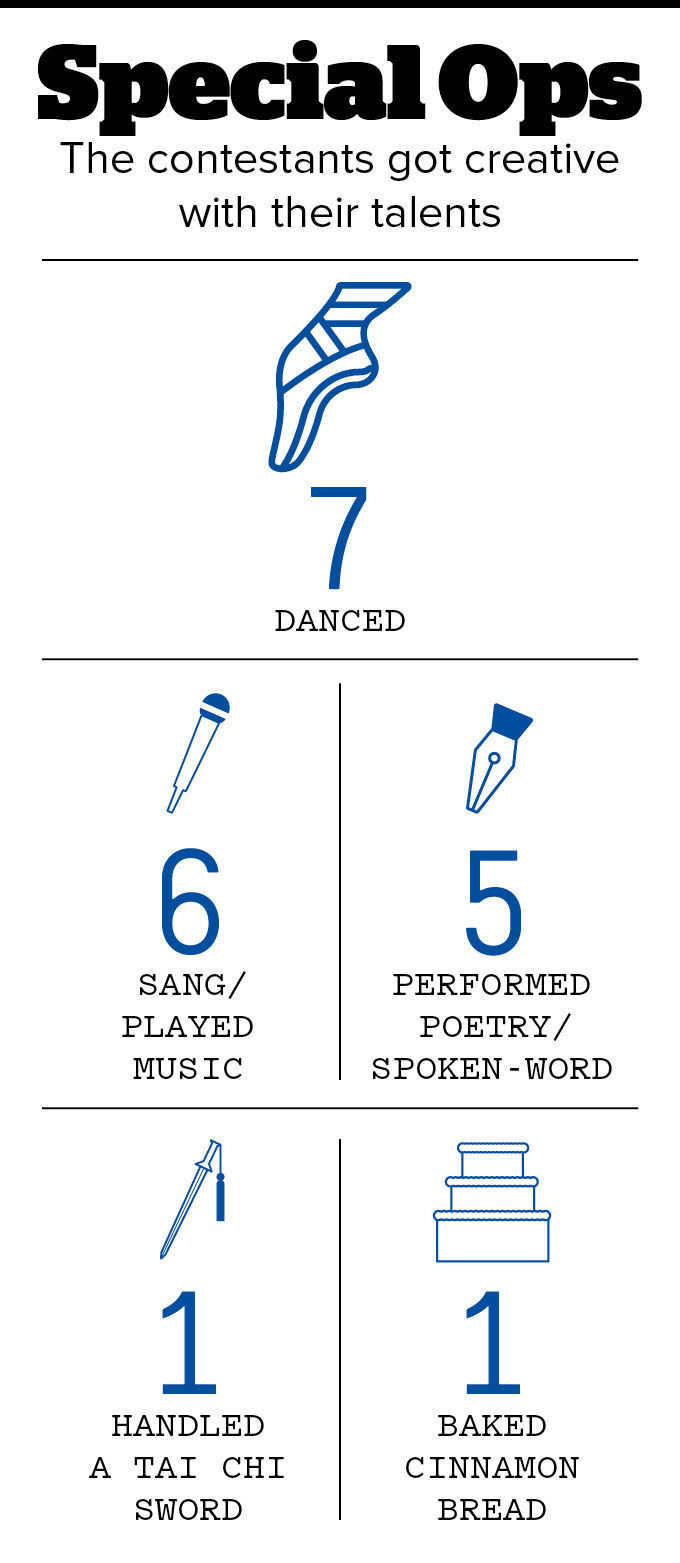

After the interviews and lunch at the casino’s buffet, the contestants returned to the waiting room for the next part of semifinals: the talent contest. In Ms. Veteran America, there are two distinct talent rounds. On the first day, the top 25 perform in front of the judges in a stuffy, windowless room at Sunset Station. Based on their performances — or, as Boothe put it, based on how hard it seems like they tried — and their scores from the interview section, the top 10 contestants move on to the next day’s finals, where they reperform their talent in front of a live audience.

The women got creative with their talents. One dressed convincingly as a World War II–era housewife — blue polka-dot dress, long red hair done up in a 1940s swirl — and hosted a faux cooking-show segment on baking cinnamon bread. Others screened documentaries shot on their iPhones about their lives, or showed off their sword-swinging abilities. One woman’s talent was particularly straightforward: correctly pronouncing her own name.

Toves wore a feathered tutu, bra, and headdress and performed a “traditional Tahitian dance that my military sisters taught me,” she said. As the self-described “motorcycle nut” shook her hips, the straw and feathers rattled, shivering like a peacock’s tail. She yelped enthusiastically and smiled at the judges like a practiced contestant.

Others were not as confident. Some trembled with nerves; others kept apologizing and asked to start over multiple times. “It’s OK, take your time,” said Jones. She wore a tailored, creaseless, military-inspired pantsuit with stiletto platform boots in matching army-green suede. She radiated such an air of authority that when she cracked a smile or laughed her loud, warm, laugh, those around her looked startled.

The judges cheered along, joked with the contestants, encouraged the ones who messed up, and, often, cried. For her talent, one woman told the story of having to deploy shortly after giving birth and return to a daughter who didn’t recognize her. “I watched my baby girl grow up through photos,” she said. When she returned from deployment, she said, “Here was this chubby baby, and it was so wonderful to hold her. But she didn’t know me.” Many judges wiped tears from their eyes and said they related.

Toves joined the military at 18 and gave birth to her son at 20, during her first active-duty station in the U.K. “I was too young,” she said. “I named him Chance because he happened by chance.” She went to work when he was 6 weeks old. The military base had a daycare, but her shifts were usually at night, so she had to find babysitters to watch her “little peanut.” “It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do,” she said. Chance took his first steps and said his first words with people she barely knew.

Turner, like Toves, was calm and assured during the talent portion. A petite woman with giant eyes, a Cheshire cat smile, and sleeves of tattoos, she was dressed in a white shirt, leggings, combat boots, and a puffy, wraparound skirt. The only returning contestant, she'd placed third last year. This time, with more free time to prepare after losing her full-time job days before the competition, she hoped to make it all the way.

Her talent was a monologue she wrote that followed four different women in four different wars, from Revolutionary to Iraq. “I come along my husband who was lyin’ on the floor bleedin’,” she said in an imitation old-timey American accent. “He told me he loved me, but to keep fightin’. So I heaved to cannon in the barrel, and I lit it.” As she switched eras, the skirt transformed into a 1950s apron, then a hippie poncho, and as she got to present day, a hijab.

Turner was a teen mom and the daughter of a teen mom. She had her first son at 16, her second at 19, and her daughter at 21. At the age of 22, Turner enlisted. She was seeking stability, financial independence, and a college education, she said. “And I got it: The military is the longest relationship I’ve ever had.”

She was deployed to Kuwait in 2012. “We were in the middle of the desert; everywhere you looked it was brown,” she said. “You wake up, go to the gym, look at the same colors and shapes every day, and go to bed. A groundhog day.” She organized a Christmas brunch and a Halloween zombie run to change things up. “I dressed up as a pregnant zombie with a baby zombie coming out of my belly,” she laughed. “It was awesome.”

But as the only female officer on special staff, it was lonely. “There’s only so many cock and balls jokes you can take,” she said. At one point she tried to give the men a taste of their own medicine by reading 50 Shades of Grey aloud in the office, but ended up spending most of her time in her shipping container turned bedroom by herself.

“The Army, ha! It’s a cross between high school and prison itself,” Turner said during her monologue, quoting from Sand Queen, one of her favorite books. She was in character as a woman deployed to Iraq. “‘Females aren’t allowed in combat! This is a man’s war!’ Seriously? ‘Cause here I am.” The judges applauded enthusiastically as she bowed.

The performances were followed by a dinner at the casino’s buffet. The women sat at a long table, eating sushi and lasagna of the same temperature and drinking cheap red wine they paid for themselves. Boothe handed out triangular glass trophies engraved “MVA 2015, The Woman Behind The Uniform” in categories like “Social Butterfly” — for the woman who was most successful promoting the contest and charity on social media — and “Hot Mama” — which “honors the woman who serves and sacrifices for not only her country, but her family as well.”

There were many tipsy tears, speeches, hugs, and raisings of glasses that continued into the casino bar next door. They talked about their experiences in the armed services: being mothers-at-arms, meeting their husbands on deployment, experiencing sexual trauma. What a relief it was to be around military women and let their “girl flags fly,” as Toves said.

“As a woman, you are constantly proving yourself to everyone around you every single day in a way that men just aren’t,” Turner said. She felt that if she presented herself as overly feminine she would be regarded as a “pretty girl” — a label, she said, one does not want to be given in the military.

“As a woman, you are constantly proving yourself in a way that men just aren’t."

Many of the others echoed this: Their colleagues, both male and female, assume the “pretty girl” only gets promoted because she sleeps with someone in charge, or someone in charge is trying to sleep with her. Turner said she watched this happen to other women throughout her career, so when she was labeled by her fellow soldiers as “basically one of the guys,” she was relieved.

Worley was not so lucky. When she was promoted to sergeant, she said, rumors began churning that it was due to a sexual relationship with her commander. Worley dismissed these claims, but when she was given the Leadership Award during her monthlong sergeant training course — an honor awarded to only one of the up to 190 soldiers who attend, and usually given to infantrymen or tankers, specializations only allowed to men at the time — the male soldiers did not take it well.

“I feel like that’s the first time I really felt that being a woman was detrimental to my career,” she said, shaking her head. As the award winner, it was her job in the program’s final week to make sure the other soldiers in the program marched in sync and remained organized. Try as she did, the soldiers disregarded her authority and instead yelled crude and cruel things at her, which she refused to repeat. Once, she said, one of the soldiers fell out of line — a serious violation of order — and began to yell the march counts over her head, drowning out her voice until she was forced to join the others and let him lead instead of her. The men in charge of the soldiers did nothing to stop him. The Army did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment on this occurrence.

For Toves, trying to be “one of the guys” was “probably the biggest downfall of my life." She would often attempt to out-drink her fellow soldiers, trying to seem cool and tough. In April 2008, Toves went out for a drink with another service member and “drank [herself] into oblivion," she said. "I couldn’t even say my name.” That night, Toves said, the man sexually assaulted her.

She didn’t report him. “I would be hung out on a line for the birds to pick at,” she worried, a fear that wasn't assuaged even by her best friend encouraging her to come forward. Toves’ alleged attacker was out of the military by then, and she just wanted to focus all her energy on helping herself.

Years later, right before she retired, when she “just couldn’t take it anymore,” she finally filed a report. The report was “restricted,” meaning no legal action could be taken against her alleged assailant, but military sexual trauma (MST) counseling would be made available to her, a Department of Defense spokesperson told BuzzFeed News.

She cycled through five or six counselors — both military and civilian — before she found a military sexual assault specialist who really helped her, but as soon as she felt they were “making headway,” the counselor was unexpectedly transferred to another station. After that, Toves tried to find another counselor through the VA but gave up, saying they confronted her with “complete insensitivity.”

VA spokeswoman Ndidi Mojay told BuzzFeed News she was aware the administration had been “tagged with a lot of challenges,” and that she thought many veterans’ complaints were fair. “But now we’re trying to change that,” she said. “When I as a woman veteran myself hear about women veterans not being provided for, I want to do all I can to help them.”

A number of other contestants told BuzzFeed News they experienced sexual assault in the military — some discussed it in spoken word or monologues during the talent portion. According to reports by RAND Corporation and the Pentagon, 20,000 of the 1.3 million active-duty personnel in the U.S. experienced one or more sexual assaults in 2014. But most of the women didn’t blame the structure, culture, or the military itself for the high number of assaults.

Even Denyse Gordon, who spent much of her reign as Ms. Veteran America 2012 speaking about her personal experience with MST and who studied it for her Ph.D., was hesitant to say the military had a particular problem with sexual assault. At least, she said, no more than the rest of the country.

“In a male-dominated culture where guys are encouraging conquests … it’s easy to see how something silly and stupid can turn into sexual assault,” Gordon said. “But it’s not just a military thing. It’s rape culture in general.”

The next morning was rough. Contestants emerged from their rooms clutching coffee and water bottles, wearing sunglasses indoors, bracing for the day of rehearsals, beauty preparation, and the finals. The women still didn’t know who had made the top 10; it would be announced live in front of the audience that evening. So at the rehearsals, all 25 would practice walking across the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, theater stage in heels to lady-power anthems. Unfortunately, a series of technical difficulties and scheduling confusion meant the rehearsals bled into hair and makeup time. “If I don’t get those eyelash extensions, shit is gonna go down,” one contestant said under her breath.

“I’m pretty nervous, yeah,” Worley said, as a volunteer stylist — from Combat Boots to Makeup Brushes, another charity for female vets — curled Worley’s fine, blonde hair. “Winning is a huge responsibility…and there’s that fear of what if I’m not enough?” Days before the competition, a family friend so close that her daughter referred to him as “Pop Pop” suddenly died. “I couldn’t think of anything else. It occurred to me not to come here at all,” Worley said. “But he was the one who wanted me to do this in the first place.” And, she said, soldiers stick to their mission.

“Winning is a huge responsibility. What if I’m not enough?”

Worley’s husband, Durwin, was in the sparse audience later that night, flipping through the large, glossy program with a short letter from First Lady Michelle Obama gracing the first page. A hundred or so of the contestants' friends and families, many of whom were dressed in decorated military formal attire, sat scattered around the large theater. Someone filming the event asked everyone to move to the first few rows so that on camera the theater would appear full.

“Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Ms. Veteran America 2015!” the masters of ceremony announced once the audience, now clustered in the camera-ready front rows, had resettled. The emcees were an unlikely pair: Marissa Strock, former military police investigator turned comedian and double “glamputee,” as she calls herself, and soap opera actor Lamman Rucker.

The contest was already out of order. Either the reigning Ms. Veteran America took to the stage and sung the national anthem before the hosts could introduce her, or someone had cut off the color guard. No one was sure, but everyone was confused. The hosts decided to move on to the main event and call the contestants onto the stage.

The first name was called, and a woman in a sparkling white ball gown walked out to Shania Twain’s “Man, I Feel Like a Woman.” The songs transitioned from Shania to Adele to Alanis Morissette to Beyoncé as the contestants streamed on and off the stage one by one. Their dresses glittered in the spotlight, but it wasn’t the traditional Miss America scene: When the women reappeared on stage, they wore combat boots under their ball gowns.

Once all the contestants were out, the room fell quiet. “And now for our top 10!” Rucker announced. They contestants flashed their boots and a little bit of leg. “Szu-Moy Toves!” Toves stepped forward, beaming. “Kerri Turner!” As more and more contestants were called, the unpracticed pageant smiles began to fade. “Heather Worley!” The remaining 15 were told to leave the stage so the top 10 could receive their applause.

And then, intermission. The contestants gathered in the dressing room as the audience milled into the lobby for cocktails. The announcement had divided the mood of the room in half. The disqualified sank into chairs and loosened their dresses. A few cried in each other’s arms or tearfully called their families, while others snuck out to the lobby to join their relatives for drinks.

Suddenly a loud bang reverberated backstage. The contestants screamed; one yelled, “Cover!” and ducked under a table. After a moment of tense silence, one of the contestants whispered, “Sorry!”

“Setting off a firecracker inside a room full of veterans is not the best idea,” Toves said between bouts of nervous laughter. The implicated veteran, who had been practicing her magic-trick–tap-dancing talent, sheepishly put her firecracker wand back in her suitcase and retreated into a corner.

The intermission was followed by the Push-Up Princess competition, a chance for any of the contestants — top 10 or not — to take home an award. The women lined up onstage at full military attention. They were still in elaborate makeup and hair extensions, but had swapped out ball gowns for gym clothes. Rucker introduced an Air Force sergeant who kept count of the push-ups. “If you break my pace, if you break form, you are out! We will go until the last woman is here. Is that clear?” she said in a piercing drill sergeant tone. “Push-up position ready. Get up! Hurry up!”

She began yelling her counts, “Up, two, three,” as the women yelled back the push-up count in unison. Two military men in fatigues ran around the stage, pointing out the women breaking form, bending their knees, or just plain giving up. The audience cheered and hollered, getting louder as women dropped out one by one.

After the winner of Push-Up Princess was declared, the top 10 finalists reperformed their talents, this time under a spotlight. For many, it was their first time performing on a stage. Turner’s routine — where she played a member of the military in different decades — was one of the first. When she was done, there was silence. Then, suddenly, a standing ovation.

Toves’ Tahitian dance was next. She shimmied onto the stage, the black-and-blue feathers of her skirt reflecting the spotlights. When she was done and backstage, her grin melted — she doubled over and held her calves. She was still feeling the repercussions of her 10 years of military broadcast journalism jobs, which involved running around with 42 pounds of camera gear and weaponry. Sometimes her knees just give out — and she hadn’t danced so intensely or worn heels for this long in ages.

Worley was one of the last. She was shaking from nerves. She tripped a few times during her dance routine, but she stayed with it. The audience clapped along, some cheering as Little Mix’s “Salute” pumped through the grating buzz of the auditorium’s sound system. Backstage she was out of breath, sweaty, flustered, her glittery eyeshadow smudged. “I was looking for my dad and my husband... I couldn’t see them.”

Worley met Durwin when she was serving abroad in South Korea in 2003 — her first time leaving the country. There was an “instant connection,” but their difference in rank was stark — he was a sergeant and she was a private at the time, and 12 years younger to boot. After two years of friendship and a long engagement, they married in 2008. The couple spent their newlywed months deployed at the Q-West Air Force base in Iraq. They renewed their vows at the ruins of the sixth-century St. Elijah Monastery as improvised car bombs went off in the distance. A few months before the end of their deployment, they conceived their daughter. “We kept it a secret because we knew if we told anyone, they’d hook me to a helicopter and ship me home within the hour,” Worley joked.

Around the time she gave birth, an injury Durwin suffered on a mission — he is bound by contract not to tell her how it happened — began to flare up. Over time, his health began infringing more and more upon his abilities, and his PTSD (which caused everything from stress to night terrors) was getting more aggressive by the week. After graduating communications school when her service was over, Worley was offered her “dream job” in broadcast journalism. But she couldn’t take it, she said, turning down the job to become his full-time caretaker. “We joke that I’m like a service person instead of a service dog,” she said, smiling and motioning to a contestant’s golden retriever, now in a tutu instead of a service vest.

“I began to feel like I was losing my identity.” She often used phrases like “take my life back” and “fill a void” to describe what the competition meant to her. Not being able to pursue her career pushed Worley to compete for Ms. Veteran America.

After the talent performances, the contestants were back in their glittery, sequined ball gowns. It was finally time for the top three to be announced. “I hope that you guys see that Ms. Veteran America is about more than pretty dresses and amazing talents and beautiful women; I prefer to call it a movement rather than a pageant,” emcee Strock said as the women shifted their weight from high heel to high heel and squeezed each other’s hands. “So, without further ado...”

“Can I get a drumroll from the audience?” Rucker said. A halfhearted drumroll followed. “Our top three are...Kerri Turner, Rachel Engler, and Andrea Waterbury!”

Cheers and screams echoed throughout the mostly empty theater. The three contestants put their hands to their faces, visibly shrieking and hugging the women next to them. They moved slowly to the front of the stage and huddled together, grinning as the cheers continued.

"I prefer to call it a movement rather than a pageant."

“One of these wonderful women warriors will be your next Ms. Veteran America 2015!” Rucker continued. The other contestants shuffled off the stage and filed into the audience, some still grinning, others disappointed.

It was time for the final question, asked onstage by the sergeant major. “To assure this is judged fairly,” Strock said, “all three finalists will be asked the same question.” The two who were not answering were escorted outside the building to stand in the persistent drizzle, where they could not hear the others’ answers.

“What effect, if any, do transgender military personnel have on military readiness? Explain your answer,” the sergeant major asked slowly.

Even though they were blocked from hearing each other’s answers, the women — who had to talk over a few heckling male audience members in military garb — gave remarkably similar responses. “I think that with the change we’ve already seen with 'don’t ask, don’t tell' being repealed, and the fight women are making for military service members, that … we need to not look at the shortcomings but look at them as a service member regardless of their gender,” Turner answered. “The military is always changing, and that we are always ready to accept any mission, and this would just be the same kind of concept.”

It was time to announce the winner.

“Could all the contestants come back out on the stage, please?” Strock said.

The 25 women filed from the wings onto the stage in uncharacteristic disorder. The nervous energy in the auditorium was palpable. A silence fell over the crowd.

“Ladies and gentlemen, your second runner-up...” Rucker said in a mock official announcer’s voice.

“Miss Rachel Engler!” The crowd cheered as last year’s Ms. Veteran America placed a small crown on her head.

“First runner-up… Andrea Waterbury!”

The crowd went wild. Turner had won. She realized it slowly, her face turning from a forced, anxious smile, to a grin of disbelief. Then it screwed up and she began crying uncontrollably.

“Ladies and gentlemen, your Ms. Veteran America 2015!” Rucker said as Turner was loaded down with a giant bouquet of flowers, a large velvet and rhinestone sash reading “Ms. Veteran America 2015,” and a sparkling crown so huge she had to hold it in place with one hand as she walked, sobbing and sniffing, around the stage.

“She really deserves this,” Worley whispered from the audience. “She’s been so committed.”

One month later, in her giant rhinestone crown and sparkling velvet sash, Turner pushed through hundreds of veterans waiting to walk up Fifth Avenue in the New York City Veteran’s Day Parade.

Alongside her husband and an MVA staffer, Turner wove through glistening old sports cars, containing equally old men in World War II and Vietnam uniforms holding carefully folded American flags on their laps. Next were the groups of uniformed airmen, Navy Seals, and Army cadets, standing in perfect formation and staring straight ahead, barely budging out of line as Turner pushed passed them with a quiet, “Excuse me.”

They were late and lost. The staffer had the map of where they were supposed to stand, but they were not sure how deep into the parade it was. With every New York City block the floats grew less impressive, the veterans' uniforms less perfectly pressed, the military personnel’s formations less exact. By the time they had reached their section, the only float was hosted by an anti-circumcision group. Most of the veterans were not in uniform but in puffy coats, some in “Make America Great Again” hats. A few sat in wheelchairs and were attached to oxygen tanks. It started drizzling and some of the marchers wrapped American flags around themselves for warmth.

“Well, that’s just disrespectful,” Turner whispered, glaring over at the group. “The flag is not clothing — if they were actually veterans they would know that.”

Still, Turner was thrilled to have the crown and, having lost her job just before going to the competition, glad to have something to take up her time.

“Isn’t this what it’s all about? Hard times?” Turner said, drawing a connection between her own unemployment and being the crowned representative of homeless women veterans. “But I believe God will provide. I feel confident that if I’m walking in faith, doing all the right things, something will happen for me.”

Many of the other contestants, Toves included, found their lives changed by the competition. The first day of the semifinals, Toves had described how much she was enjoying retirement — trips to Hawaii with her husband, drinking margaritas in the daytime, signing up for boozy painting classes with her sister.

But soon after returning home, Toves began to be offered paid speaking engagements about Final Salute at colleges, fairs, panels, and music festivals. “Just being out there talking to people, having conversations about homeless women vets. It’s amazing … people love what I’m doing.”

Despite the excitement, Toves wasn’t “all better,” she said. She still had those days, days when it’s hard to sleep and she feels “so yuck,” days when her MST comes back.

She is still not in therapy, and fights the hard days with willpower. “I’m like, Get out of this! Lock it up, airman!” Working out helps, reading books, painting — things she always loved doing but that “got blocked out.”

Toves also said that while she she wants to spread awareness about the many hurdles servicewomen face, she is not yet ready to become a spokesperson about her experience with military sexual trauma. She hopes to be able to write about it someday.

When Worley first auditioned for the competition, her family friend Pop Pop had promised to help out with Durwin and the kids, if she should she win and need to travel. “But when he died, I found myself torn between a responsibility to my family and a responsibility to my sisters [in arms],” Worley said. “When they didn’t call my name for the top three, that tension disappeared.”

Still, the competition awakened in her a better sense of her position in society — not just as a woman veteran but as a woman in general. “Having to study myself that closely for the competition, especially the interview portion, made me realize how often I feel I have to justify my existence.” This justification manifested itself in her speech patterns, Worley said, such as using “just” or “only” when talking about herself, subtle ways she thinks many women subordinate themselves. “We are not just women, and we are not only mothers, and we are not just veterans,” Worley said over the phone from her home in Georgia. “We are a complex combination of all those things.”

Turner stood in the November drizzle for hours. Floats of veterans surrounded by short-skirted cheerleaders passed by. The American Bombshells, a doo-wop group of non-military women dressed in sexy World War II uniforms, waved to her. Finally, it was her turn to walk up Fifth Avenue. She mostly walked alone, her husband falling behind as she ran over to the parade barricades to thank scattered veteran onlookers for their service. Many of them seemed confused as she handed them a small coin made by the Ms. Veteran America competition emblazoned with the words “The Woman Behind The Uniform” on one side and an embossed picture of heels and combat boots on the other.

“Did you serve?” many of the women veterans Turner approached asked, eyeing her sash. “Why isn’t she in a bikini?” many of the older male veterans asked each other, barely out of her earshot.

By the time she reached the main event of the parade — a red carpet and a stage set up on the steps of the New York Public Library — most of the onlookers had dispersed. An announcer read descriptions of everyone in the parade into a loudspeaker. Turner walked past, her crown sparkling in the sunlight that had just emerged from the clouds.

“They didn’t announce her,” her husband whispered.

Turner smiled, waved, and kept walking. ●

CORRECTION

Andrea Waterbury was the first runner up, and Rachel Engler was the second runner up in the Ms. Veteran America competition. A previous version of this article incorrectly stated their finishing positions.