Suicide rates in the U.S. have increased by 24% since 1999, with white and Native American women seeing the biggest increase, a new study from the U.S. Department of Health shows.

The study, conducted by Sally Curtin, Margaret Warner, and Holly Hedegaard of the CDC, discovered that despite generally declining mortality, the number of suicides has greatly increased in the past 15 years in the U.S., becoming one of the 10 leading causes of death across all ages and genders since 1999.

"1999 and 2000 is the recent low point in ... suicide rate and it has increased since then," Curtin told BuzzFeed News.

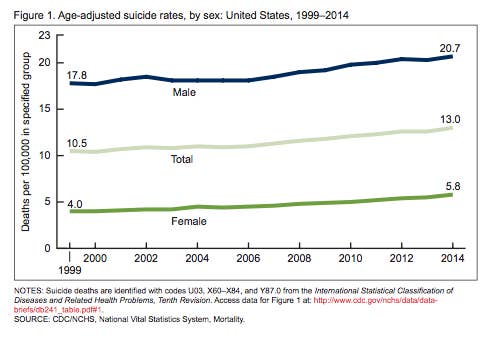

Before 1999, there had been a period of "nearly consistent" decline in suicide rates since 1986, the study said, but in the millennium the rates took a turn upward, increasing from around 10 people per 100,000 to 13 people per 100,000.

Though it was creeping upward since 2000, in 2006 the speed of increase in suicides doubled from 1% to 2% per year.

"Suicide deaths are due to a confluence of factors," Curtin said, saying that a widespread increase in suicide cannot be traced to one specific trend. "There are psychological, biological, and societal factors."

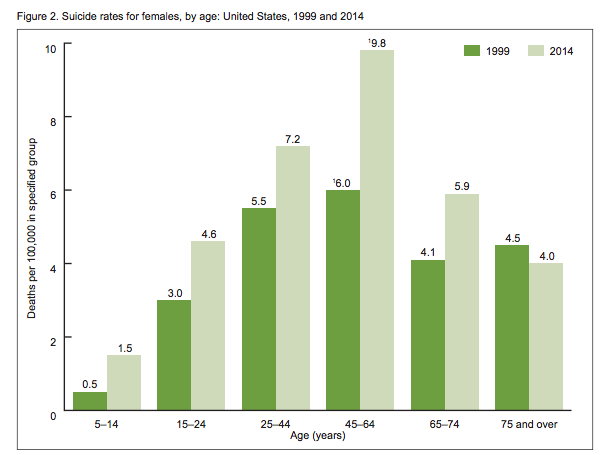

The largest jump in suicide rates since 1999 by gender was a 200% increase of suicide in girls between the ages of 10 and 14. The second largest was women between the ages of 45 and 64, at 63%.

The rate of suicide for men has been consistently higher than for women for decades, but starting in 1999, women began to catch up.

In 2014, the rate for men was more than three times that for women. But the percent increase throughout the study was much greater for women — an average of 45% increase — versus men's 16% increase.

The suicide gender gap was smaller in 2014 than it has been in decades.

A supplemental study tracking the suicide rates among genders and races in the U.S. showed that, for the first time since the government began keeping records of life expectancy, the CDC said white women's life expectancy took an incremental but unprecedented change.

Multiple CDC studies show that the life expectancy for non-Hispanic white women in the U.S. declined by one month — from 81.2 years to 81.1 years — from 2013 to 2014.

One of the report's demographers, Elizabeth Arias, told NPR that she believes this decrease is connected to the large increase in suicide among women over the past 15 years, as well as an increase in alcohol and drug poisoning — the abuse of which which is often connected to suicidal tendencies, the CDC reports.

These reports come just a few months after a non-CDC study by Princeton economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case demonstrated a rise in middle-age mortality among white people, which they connected to an increase in suicide and drug and alcohol abuse.

Native American women under 75 saw the largest increase in suicide rates of any demographic at 89% since 1999, while white women under 75 saw 60%.

Middle-aged white women were hit the hardest, with women aged 45 to 64 in 2014 dying from suicide 80% more often than in 1999, a rate three to four times higher than for women in other racial and ethnic groups.

Black men and the elderly were the only demographics to see a decrease in the number of suicides since 2014.

Though men over 75 remained the highest suicide demographic in the country, they saw an 8% decrease since 1999. Black men also saw an 8% decline.

The number of suicides involving guns and poisoning declined from 1999 to 2014, but the use of suffocation increased.

About one in four suicides in 2014 were due to hanging, strangulation, or other forms suffocation, in both men and women.

In 1999, suffocation was less than one in five, but the use of guns was much higher for everyone.

Poisoning, which includes purposeful drug overdoses, became the most used method in 2014, when in 1999 it was guns.

"Although the extent and direction of misclassification of suicide deaths is unknown," the supplemental report stated, "numbers and rates for these racial and ethnic groups are most likely underreported."