Some days, the calmer days, Tiffany Malcousu will stay home and work remotely, her 12-year-old son on his laptop at the other side of the dining room table, pretending he and his mom are coworkers.

She got them a Keurig machine recently and he loves working it, pushing down on the lever and watching the steam rise. Most mornings he’ll make his mom a cup of coffee while she makes him hot chocolate, and they’ll sit and drink it together as they start their work. Sometimes, when he doesn’t have class, he’ll put a blanket down under the table and take a nap at her feet as she types and takes Zoom calls.

Other days she’ll get an urgent call and have to rush out of the apartment, just after waking her son for virtual school, and drive to whichever of the 11 homeless family shelters she works with that need her most that day. Her gas and E-ZPass bills have gone way up during the pandemic, and she feels like she’s perpetually pumping gas into her car, watching the numbers rise.

Tiffany is the director of children’s services at Win, a nonprofit that is the largest conglomerate of shelters and supportive housing for families experiencing homelessness in the city. Before the pandemic, she oversaw Win’s teachers and had meetings with executives. But now, Win’s staff is one third the size it was pre-pandemic, and a lot of the on-the-ground work falls to her. Her days and hours are unpredictable, and she’s found herself doing jobs she didn’t sign up for: school administrator, communications person for the city, tutor, therapist, tech person.

On those hectic days, her son will stay in their Brooklyn apartment, taking his remote classes on his own. Her father, his grandfather, lives upstairs and checks in every few hours.

“I opted to do 100% remote learning for him. School is too risky, and it’s a blessing he’s old enough to do it,” Tiffany told me when we first met in September. “The families in shelter, they don’t have that option.”

The start of school this fall has been complete chaos for nearly every parent, teacher, and student in the US. Reopening plans have changed constantly and many parents weren’t even sure whether their kids were physically going to school or not until the last minute. As schools opened in Southern states in August, parents watched for coronavirus spikes. And in many other places, including New York, the first day of school kept being delayed. Originally it was supposed to be after Labor Day, on September 8, then it got delayed until the 16th and then the 21st. City officials finally opted for a staggered system (different age groups starting in person on different weeks). But then, just as younger children were finally starting class in early October, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo ordered schools closed in areas where coronavirus rates were spiking. This roller coaster forced parents all over the city to rearrange their work schedules and childcare plans, to beg more favors of relatives or shell out more money for babysitters, to try to relay city policy to their children in hopes of explaining why they couldn’t see their friends or teachers just yet.

But this chaos has already been widely reported. From local education journalists detailing the policy changes and union negotiations affecting students and parents to poignant personal essays from white-collar parents attempting to balance working from home and making sure their kids are actually learning remotely to medical workers forced to isolate from their families to do their jobs to the infamous learning pods of the rich and ultrarich, in some cases worsening school segregation and harming public school enrollment.

For those in shelters without a steady address, limited or no internet access, and enough privacy to quietly study and attend classes, the chaos everyone is experiencing is even more pronounced. And for the children, these access issues have even higher stakes.

For those in shelters without a steady address, limited or no internet access, and enough privacy to quietly study and attend classes, the chaos everyone is experiencing is even more pronounced.

Chronic absenteeism not only impedes a child’s future by making them less likely to graduate on time — if at all — and removes them from an important support system, it’s also illegal. Parents could face fines for their children’s absence, or, in some cases, Child Protective Services could even get involved.

Students experiencing homelessness are already at a significant academic disadvantage, and the pandemic will likely only widen the gap. According to the National Center on Family Homelessness, students without housing are twice as likely as students with homes to get suspended, repeat a grade, drop out of high school, or be expelled. This is often due to a lack of school supplies, frequently changing schools, and an unstable or violent family environment. Because adults without high school diplomas are less employable, or can often only get jobs at lower pay levels, they are more at risk of becoming homeless themselves as adults, continuing the cycle.

While shelter workers all over the country are struggling to manage these issues, New York City, with its sprawling homeless shelter system, is an extreme case. Over the past few years, New York City’s homelessness has reached the highest recorded levels since the Great Depression. Families, often led by single mothers (9 out of 10 families in Win’s shelters are led by women), make up about 65% of that population. Around 1 in every 10 of New York City’s public school students is experiencing homelessness — that’s over 100,000 children in transitional housing, most of whom are Black and Latinx. Only around 7% of unhoused New Yorkers are white, according to the Coalition for the Homeless.

The people left to help mitigate this compounding crisis are shelter workers like Tiffany. But like Tiffany, they’re often parents who are dealing with some of the same education and childcare struggles as the families they’re trying to help. Without the proper support from the city and state, an already fragile system could crumble under the strain of a pandemic, leaving families without housing to suffer.

“I think shelter staff have mostly been left out of the conversation and praise for essential workers, and that’s a big mistake,” Marjorie Jeannot, the residence director for the BronxWorks Willow Avenue family homeless shelter, told me over the phone in early October.

“Our staff have been on the front lines every single day since March, doing incredible work,” she added. “I don’t want them to be the forgotten group.”

When I first met Tiffany in mid-September, it was during New York’s third attempt at launching the first week of school. It had just started to rain, so we sat in the echoey lobby of Win’s newest family shelter in Park Slope, Brooklyn, 6 feet apart. Tall with smiling eyes, she wore a crisp black suit, stilettos, and a mask that read ”Black Queen” in shiny pink font. Because of the pandemic, we could only meet once for about an hour.

Tiffany, “a fabulous 40 years old,” worked as a school teacher for 17 years before joining Win two years ago.

Throughout the interview, several shelter staff and a member of Win’s press team stood nearby, watching us silently. I was told I wasn’t allowed to speak to Tiffany without the supervision of Win’s press team, and while Tiffany was often very open with me, it sometimes seemed like she was holding back, painting a shine on a hard job. I felt this way with several of the shelter workers I spoke with from other organizations as well — a suspicion of the press, or concern that something they said would upset the New York departments of Education or Homeless Services, making their jobs harder. (Neither department responded to a request for comment about this concern.)

Tiffany and the press team told me they chose the shelter — named after Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress — because it was their newest; it had only been open for a few months. The others, which had been in use for decades, were older and busier.

I stayed on the ground floor during my visit, which held the lobby and administrative offices. Across a large, empty courtyard, was a brand-new, as-yet-unused daycare center and classroom for toddlers. The pristine building is all glass, concrete, and steel, resembling the new high-rise condo buildings in Brooklyn’s many gentrifying neighborhoods. In September, 80 families were staying on the floors above, each in individual units.

“Our staff have been on the front lines every single day since March, doing incredible work,” she added. “I don’t want them to be the forgotten group.”

In normal times, Win’s shelter would hold classes and activities for families in community areas and their kids would be able to play together. But since March, Win, along with other city-funded shelters in New York, implemented strict coronavirus protocols: Masks are required outside of shelter apartments, and social distancing from staff and other residents is encouraged. At Win, activities are online, or bags of crafts or games are distributed to be played in individual units.

As Tiffany and I spoke, information packages about school registration, voter drives, and remote learning for high school students, written in both Spanish and English were displayed on a folding table in the shelter lobby. Transparent bags containing apples, crackers, and milk, sat next to them. Mothers pushed heavy strollers through the lobby, plastic hoods protecting their babies from the rain. Or they dragged their kids along as they grabbed at the bags of snacks, one pulling her tiny mask over her eyes to hide from us, giggling. Tiffany motioned the families toward the tables, instructing them to help themselves.

“It’s been a tough few weeks for these parents, a lot of hard choices,” Tiffany told me. “We don’t want clients to leave their kids in the unit alone, but we understand the need to work, it’s what they need to do to get out of the shelter. We understand that they have their fears about sending their children to the school building, and we don’t want them to have to choose between the safety of your children and providing a living for your family.”

New York City has attempted a “blended” school reopening program, which allows parents to opt their kids into going to school a maximum of two days a week, with online learning for the other three. Parents could also choose to keep their kids remote the whole week, the option Tiffany chose for her son.

Kids under the age of 18 in New York shelters generally aren’t allowed to stay in their units alone (though the city’s Department of Social Services has started making case-by-case exceptions for older children during the coronavirus outbreak, a spokesperson for the agency told me over email). Despite this, most of the families in Win’s shelters — and around half of families in New York generally — have chosen to keep their kids completely remote. The NYC Department of Education (DOE) has implemented COVID-19 safety protocols in public schools, and random testing of students and teachers, but several parents I spoke to said they just didn’t trust the schools to keep their kids safe from the coronavirus.

This introduces a catch-22 for some families living at shelters: In order to continue to receive subsidies or unemployment from the government, parents must be working or actively looking for work, but with many shelters’ childcare services limited or paused during the coronavirus, parents who don’t have family or neighbors available to watch their children are often forced to stay home with them, making them unable to work and potentially keeping them all in the shelter system even longer.

In an attempt to help mitigate this problem, the New York DOE introduced a program called Learning Bridges, which provides childcare and supplemental teaching during the workday. Only kids enrolled in “blended” learning qualify for the program, leaving parents with fully remote kids in the lurch. Qualifying kids gather in socially distanced classrooms during the days they’re supposed to be remote, taking classes separately on iPads with headphones. The program gives priority to families in shelter and transitional housing, those receiving child welfare services, children of essential workers, and students with learning disabilities. However, it is only accepting 100,000 students in total. There are more than one million public school students in New York City.

A mother of one of the families I spoke to at Shirley Chisholm, Jennifer Bones, 32, had been forced to choose between a job and her kids, she said. She worked for New York City’s Parks Department for a while, but then three of her family members died from COVID-19, as well as her best friend’s dad. Her youngest’s father, who is staying with them in the shelter, works as a chef with long, unpredictable hours. Not working is making her feel “crazy,” she said, but when she was working she had to leave her kids with friends, family, or neighbors in the shelter. She felt it was just too dangerous.

“In the situation I’m in, I do have to work, in order not to stay here, but I’m not gonna do anything until I can be sure that everything is OK,” Jennifer told me.

“I always hear myself talk, and I’m like that sounds crazy, you’ve gotta get out of here,” she continued. “This isn’t home, and I’m trying to get my kids home, but in the same token, I just want them to be safe.”

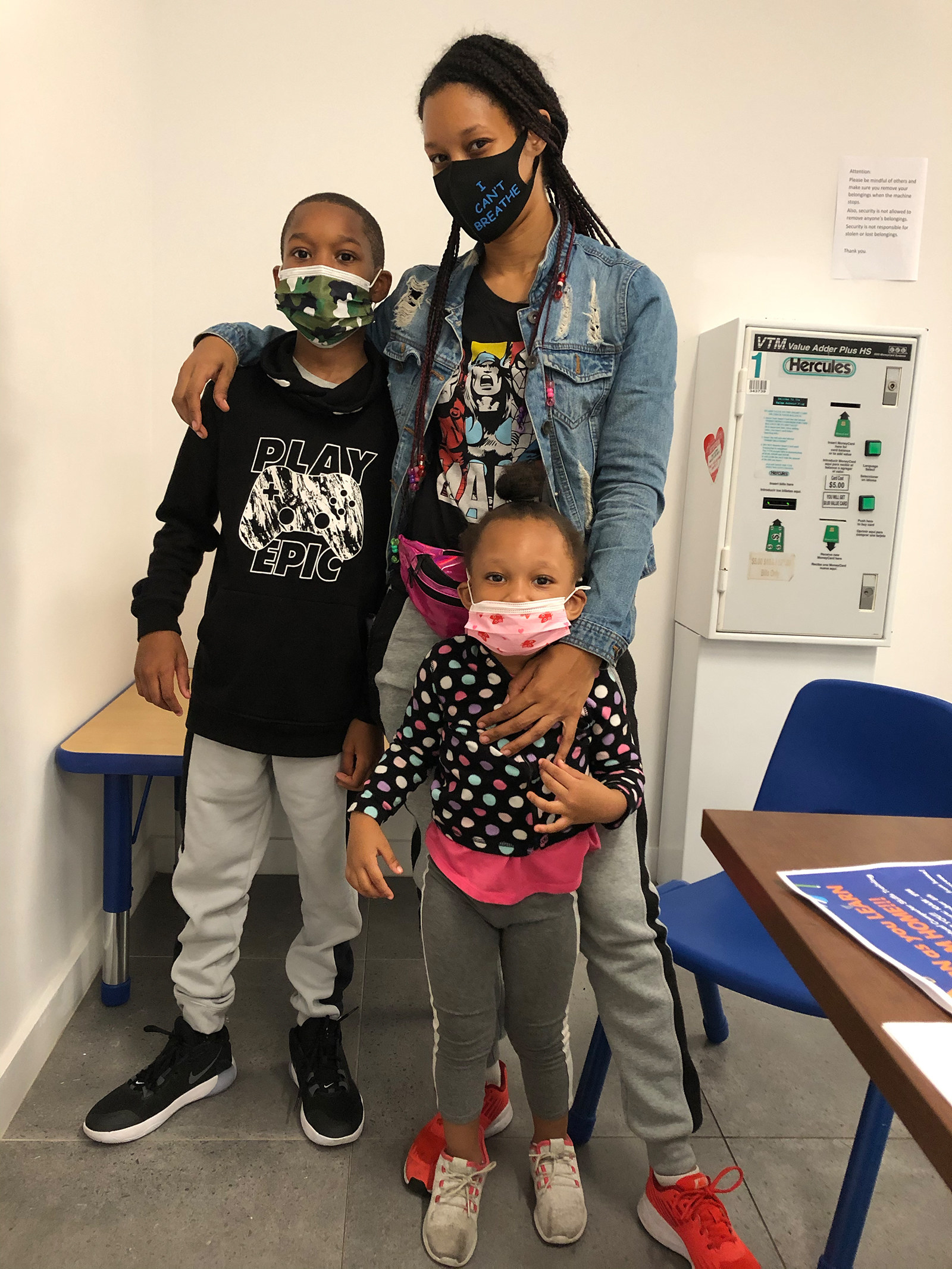

As we spoke, Jennifer sat in the chair in the lobby that Tiffany had just vacated to take a call, and Jennifer’s 9-year-old son, Kordae, stood behind her playing with her braids. Her 2-year-old daughter sat on her lap, pulling at her own tiny mask.

Before the family got to Shirley Chisholm they were staying in another family shelter. But the city had tried to transfer them out of that one and into another shelter with a bad reputation that Jennifer said she couldn’t even think of living in. It wasn’t Win’s, but she wouldn’t tell me the name.

“There were too many bugs!” Kordae chimed in.

“And other stuff,” she added with a look toward me, indicating it was “stuff” she didn’t want to discuss in front of her kids. “I was not keeping my children there,” she simply said.

So she stayed on the phone with 311 “all day every day, until they got us out of there,” she said. “So now we’re here, and I’m happy we’re here because it does make remote learning so much easier. I’m less stressed because of the surroundings.”

Marjorie Jeannot, the residence director for BronxWorks, gets up most mornings at 4:30 a.m. to go for a run or a walk near her home in Long Island before commuting to the Bronx.

Dawn, when everyone else is asleep, is the only time she has to herself the entire day, she told me. Sometimes she gets calls late into the night — 1 or 2 in the morning — to help manage some crisis at the shelter.

Family homeless shelter workers’ jobs have always been difficult: They help the families find work and stable living situations to get out of shelters, help them get mental health and medical care, manage childcare, help their kids succeed in school, and manage constant crises, often at all hours. Marjorie moved from Haiti to New York when she was 14, and has worked at Bronxworks in different roles since she graduated from college about 20 years ago. But she’s an anomaly, she said, as shelter work generally has a high turnover rate. Most of her staff only last a year or so.

“My own mother, I think her prayer for me would be, ‘Oh god, get out,’” Marjorie said. “But I just happen to love it.”

The sheer volume of people in the system is overwhelming. In July 2020, there were 13,046 families with 19,278 children in the New York homeless shelter system, about two-thirds of the total shelter population. That’s just in one month, that number fluctuates wildly, and thousands more families are experiencing homelessness outside of the system, bunking temporarily with friends, neighbors, family members, or on the streets. Win houses around 4,700 people a night, and BronxWorks has capacity for 276 families. Most of the kids in those families attend different schools, all over the city, making coordinating their education during the pandemic an even more complex task.

“This isn’t home, and I’m trying to get my kids home, but in the same token, I just want them to be safe.”

But the high turnover in these jobs is less about the complexity of the work than it is about how personal it can get, Marjorie told me. Shelter workers have to deal with highly intense situations and make hard decisions, ones that can have tremendous impact on the lives of the families in their care.

“It could be a suicide, or an attack. It could be some sort of domestic violence situation. It could be a runaway, which we have a lot,” Marjorie told me over a video call from her office. “Sometimes you have to get Child Services involved, and that’s always hard,” Marjorie added. “If you’re getting a child removed from their home, a parent isn’t going to be happy, even if it’s in their best interest.”

Marjorie told me that her staff gets threatened by people in the shelter regularly. She herself has been attacked by clients on several occasions, she said, and had all four of her tires slashed.

During the pandemic, the amount of “negative incidents,” as Marjorie put it, has largely stayed the same, but they’ve become about people refusing to socially distance or wear masks, or keep to the strict rules the shelter put in place to try to mitigate the spread of the virus.

“The stress is really high for staff in the shelter system. It’s good work, but it’s hard work. It’s a job you have to love to remain in,” Marjorie said. “And the pandemic has certainly added another layer of stressors, I would say. It’s been really hard.”

For some shelter staff, this was just too much. When the severity of the coronavirus became clear, many shelter workers quit their jobs, unable to leave their children or parents at home alone, or afraid that it put them and their families at higher risk of catching the virus. Win had to significantly cut the number of staff on-site to enable social distancing, and Marjorie’s shelter has been understaffed for months.

As a result, Tiffany, Marjorie, and their remaining staff are doing the jobs of the colleagues they can’t replace.

“I’ve never really had a work–life balance, which has been a concern for everyone that knows me,” Marjorie added. “But with the uncertainty of this time, I’ve had to take care of both clients and staff, make sure everyone is OK all the time, and it’s just become so much harder.”

When Tiffany took the job at Win on, she told me, she never expected she would spend so much of it watching YouTube videos, trying to figure out how to fix iPads for students to get online to take their classes.

“I have a bunch of text messages already this morning of kids starting school soon and the tablets not working,” Tiffany told me, waving her phone. Even if the iPads are functional, she added, sometimes the parents don’t know how to log their kids in or what the online schedule is.

“There are times where I've helped kids log on, or say, ‘You're supposed to be in this Zoom classroom with your teacher,’ and the teacher would say to me, ‘Thanks for helping, because we haven't seen this child for a couple of days,’” Tiffany said. “And it's not the fault of the parents. It's just not knowing.”

“I have a bunch of text messages already this morning of kids starting school soon and the tablets not working.”

It even happened to her own son. He had been in his online classes all week, completing and turning in all the assignments, his face floating in the little video box next to the 40-something other kids in his class. But he had forgotten to hit submit on the online attendance sheet in the morning. So as far as the school was concerned, he hadn’t shown up.

And the New York DOE hasn’t been making managing these issues easier, Tiffany said.

“There’s no communication at all, we haven’t received anything from DOE,” Tiffany told me. This is a point she reiterated frequently, both during phone conversations and in person. “There's so many obstacles and challenges and scenarios that we present to them, and yet we get no solutions or answers yet.”

Over the summer, Tiffany spent her days making sure families understood the “blended” learning system and knew what schools their kids were going to, how to log on to the classes, how to pick up workbooks and textbooks for their kids, and how to get them to school if they were going in person. DOE didn’t have finalized transportation contracts with school bus companies until days before the original first day of school was supposed to start in mid-September. This was a significant problem for parents experiencing homelessness, as they often try to keep their kids in the same school no matter what shelter they move to, to give them some stability. Kids in shelters often have to commute hours across boroughs to get to their schools.

The only reason Tiffany was able to provide the families with this information, however, was because she is a parent herself. Tiffany regularly receives information from her son’s school about DOE decisions, which she immediately disseminates to her staff. She is even still accidentally signed up for messages about her son’s old charter school, which has helped her know what the plan is for unhoused families whose kids go to charter schools.

“I am taking my home to work every day to do this. We would be lost if I didn’t have any children,” Tiffany said. “Without me checking my personal information, we just wouldn’t have been able to do our jobs.”

Families experiencing homelessness can be hard for schools and the DOE to get in touch with. Most families don’t stay in one shelter for more than a few months, shifting to another shelter or temporary housing with friends or relatives, making them hard to locate. Many families in shelters, including two other mothers I spoke to, are escaping domestic abuse situations, and have changed their phone numbers or emails to be harder to find. Other parents are not fluent in English, and the schools and department haven’t communicated with them in their language. Without shelter workers communicating information about schooling, they might never receive it.

In August, Win’s CEO Christine Quinn wrote a letter to New York Mayor Bill de Blasio and New York's DOE Chancellor Richard Carranza, outlining all the issues the families in their shelters were facing, and chastising them for their “inadequate communication.”

BronxWorks was facing a similar issue over the summer, but just as school started up, the DOE sent a representative to stay on-site, helping with technological issues and getting answers directly to the parents.

NYC DOE told me in an email in October that it has several programs to help combat chronic absenteeism, especially for students in transitional housing, and that there are 117 DOE representatives who work in shelters across the city. However, those representatives worked remotely after school shut down in March and didn't work over the summer, so the city hired 100 “community coordinators” to help students in temporary housing in their absence. The DOE spokesperson also told me that their agency met with Win staff in June about technological issues facing the families and responded to a number of emails from Win staff over the summer. But to Tiffany, this wasn’t enough.

“I think they just don’t realize that we are the bridge between what the kids are supposed to be doing, and making sure they know that and they can do it,” Tiffany said.

But New York’s DOE has been trying their best in an arduous situation. Reopening schools safely, trying to manage the needs of the millions of public school students and their parents, as well as the safety concerns of teachers and their union, is no small feat.

In March, as schools shut down, the NYC DOE made a herculean effort to get more than 300,000 iPads with built-in internet to any kids who needed them across the city, including around 15,000 in shelters. In early October, a DOE spokesperson told me that the city is buying 100,000 more devices for students in need, prioritizing those in shelters.

Though it’s clear the City has been overwhelmed. The DOE is understaffed, just like the shelters, and the federal government hasn’t been helping where it could, education advocates I talked to said. Trump at first refused to provide aid funds to help the city, then Congress reportedly short-changed New York on the aid it did provide.

“We’ve been working hard to ensure our students experiencing homelessness have the tools and resources they need to succeed this school year, whether they are learning in school or remotely,” Sarah Casasnovas, a spokesperson for the NYC DOE, emailed me in response to questions about New York’s plans for students without housing.

A DOE spokesperson told me that they believed the state and federal government response did not match the severity of the pandemic and the financial crisis, and that more support for schools, students, teachers and staff was necessary to get through this critical time.

New York isn’t alone in having its reopening plan go haywire. No state seems to have the right answer during an unprecedented pandemic.

In August, schools in several states, including Georgia, Indiana, Tennessee, and Louisiana, closed their doors just days after reopening for in-person learning due to coronavirus outbreaks among students and staff. This was damaging to those states’ students without homes as well, as coronavirus outbreaks tend to affect lower-income people with unstable housing and healthcare the most severely, putting them at increased risk.

In California, school reopening has been very limited, with the vast majority of students learning remotely. This prompted mayors from the state’s 13 largest cities to call on California Gov. Gavin Newsom to make in-person learning more widespread, specifically referencing its negative effect on students without homes and their lack of access to remote learning.

“So what’s to be done?” Marjorie said when I asked her what she thought the best plan for schooling during a pandemic should be. “Just try our best I guess, get as much support as we can.”

And they’ve been doing just that. Win has been using fundraising dollars to hire IT professionals, buy students headphones, laptops, and Wi-Fi hotspots. BronxWorks converted its recreation room into socially distanced classrooms, taking down colorful pictures and putting up smartboards, spacing school desks 6 feet apart from each other, and nailing plexiglass to the front and sides, creating small transparent cubicles. When Marjorie and I last spoke, it hadn’t opened yet, but the plan was to sit kids with their devices and headphones at the different desks, all learning different lessons in different schools all over the city, but all turning to the same on-site tutors for in-person help.

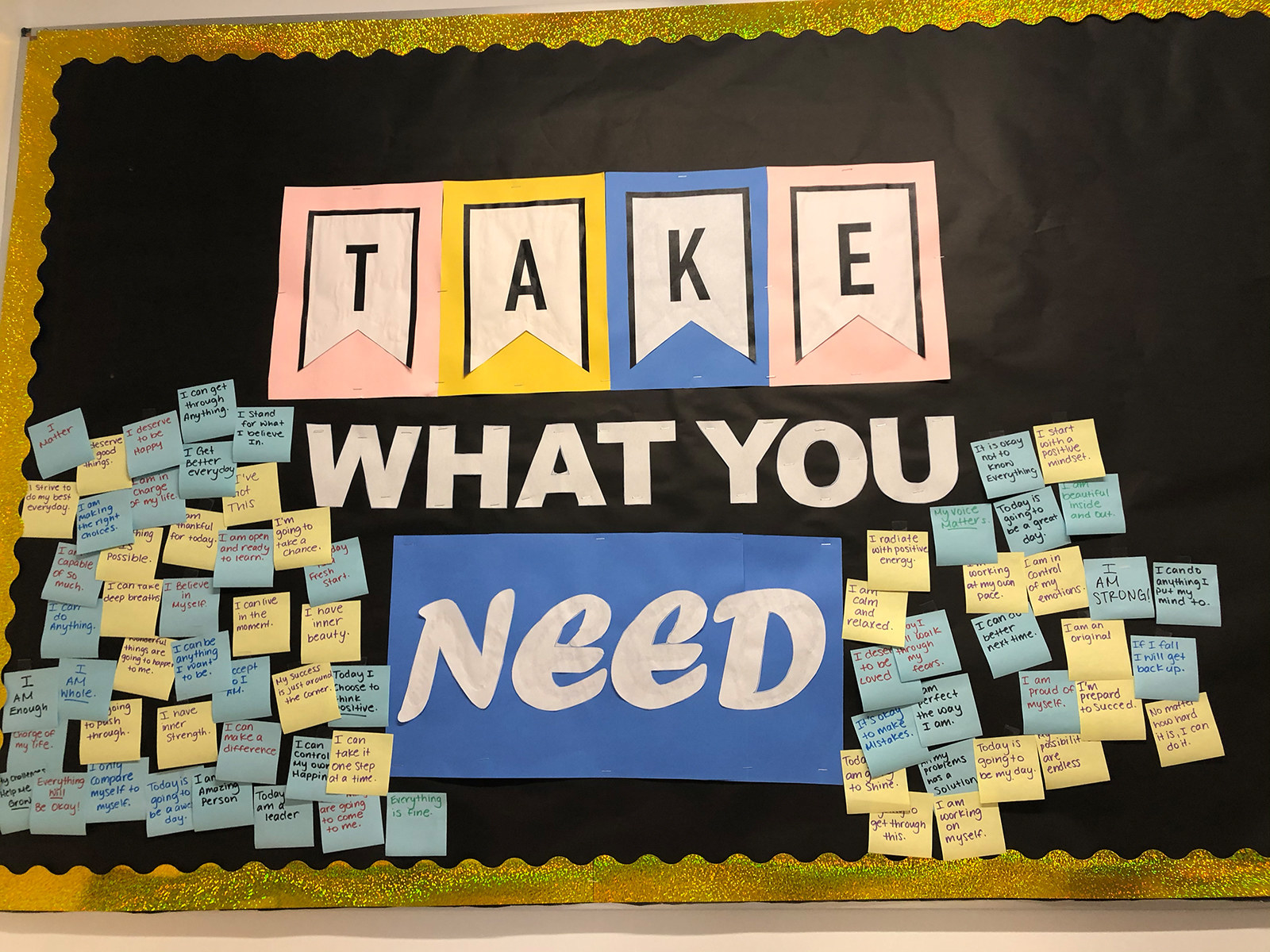

At the end of my visit at Win, they took me on a tour of their own brand-new classroom. It was decorated like a kindergarten classroom, but the city hadn’t given them permission to open it yet. Pictures of important Black historical figures covered the walls, and construction paper cutouts of butterflies fluttered around the doors. The toys and miniature furniture were untouched by kids, some still in plastic wrapping, giving the room the uncanny feeling of a museum exhibit.

A large sign on the wall read “TAKE WHAT YOU NEED.” The letters were surrounded by sticky notes, all in the same handwriting, featuring different inspirational phrases. “I am capable of so much,” “I can get through anything,” “Everything will be okay,” and “No matter how hard it is, I can do it.”

“We can’t wait for this to open, for us to be able to provide these kids with as much support as we can,” Tiffany said. “But that support will need to change of course, depending on what happens as school reopens, as it goes on.”

“And that’s the thing isn’t it,” Marjorie said when I asked her about her plans going forward. “No one even knows what the future holds, but especially not now. We just have to wait and see.” ●