LITTLE ROCK, Arkansas — The car pulled up to the clinic and she threw herself out before it had fully stopped, running toward the door. She was doubled over holding her stomach, with her other hand on the ground to keep herself from collapsing. Sweat rolled down her forehead and tears clouded her eyes; she could barely see anything except the pavement in front of her. She had never experienced pain like this.

“I need to get inside,” she said through gritted teeth to the security guard helping her up and onto a bench. She couldn’t be let in just yet, other people were checking in. “It feels like I’m having 10 periods.”

Once the nurse saw her, she knew there wasn’t time for a proper check-in. They rushed her straight past the security check, through the clinic, and into the procedure room; gave her the anesthesia as soon as they could; and called for the doctor.

At 21 weeks pregnant, this was her last chance to get an abortion.

A fetus cannot survive outside of the womb at 21 weeks, but Arkansas has a ban on abortion after 22 weeks from a patient’s last period, and the clinic doesn’t perform abortions after 21 weeks from a patient’s last period (which it estimates to be 19 weeks from conception).

A., who asked that her name not be used because she hadn’t told any of her friends or family she was pregnant, had been trying to get an abortion since she was six weeks pregnant. She didn’t have the money herself, and even if she did, there is an ever-dwindling number of abortion clinics in the South. She turned to the man who’d gotten her pregnant, who at first offered to pay for the abortion but, based on texts reviewed by BuzzFeed News and interviews with A., later reneged.

A. may be one of the last women able to get an abortion this far along in Arkansas. A new state law banning abortion after 18 weeks of pregnancy is scheduled to go into effect in July. Little Rock Family Planning Services, the clinic where A. had the abortion, has vowed to join other abortion rights organizations to challenge the ban, but it’s not clear whether the courts will block it.

Friends used to tell her she looked like Miley Cyrus, she said, standing in her hotel room the morning before the abortion, and even in her second trimester of pregnancy, wearing an oversized T-shirt and socks with Birkenstock sandals, you could still see it.

A. had already traveled to Little Rock in an attempt to get the abortion four or five times. Maybe more than that, she told BuzzFeed News on the drive to the clinic in early June; she had lost track.

“Since March 8, I’ve been trying to get here every weekend,” she said. “I’m still not convinced it’s gonna happen, something else will go wrong and I will have to have this baby.”

The first barrier to her getting the abortion was the man who got her pregnant. He wasn’t someone she knew well, and they were never in a relationship.

“Something else will go wrong and I will have to have this baby.”

She found out she was pregnant and told him soon after, text messages provided to BuzzFeed News show. She told him she was getting an abortion and that she didn’t have the money for it. He said he would pay, and she was grateful.

She was about to get her degree, and she couldn’t let this mess it up. She felt like the “fuckup” in the family, she said, and this was her chance to set that straight. She was good at what she was studying, knew what she wanted to do, and, for the first time, saw a clear path to do it. But she had immense debt, including student loans, and the fees she had to pay to finish her degree were exorbitant.

She took some extra jobs on top of her schoolwork, but soon she started getting intensely ill. She had severe, chronic morning sickness (she prefers the medical term “hyperemesis gravidarum” because she believes it more accurately portrays how horrific she was feeling) and spent hours every day on the floor of her bathroom throwing up. For weeks she felt weak and cloudy and couldn’t keep anything down but bread. She lost nearly 25 pounds, she said, and was having a hard time driving, working, and doing schoolwork. Sometimes it got so bad that she considered calling 911, but she didn’t want to have to pay the hospital bills. In order to get to the appointment and back, she needed help.

At first the man was comforting and helpful. He would bring her groceries and walk her dog. When she was six weeks pregnant, he drove her to her first appointment at Little Rock Family Planning Services, where the clinic workers confirmed the pregnancy, told her her options, read the state-mandated script about the risks of abortion and of continuing the pregnancy, and made a follow-up appointment after the mandatory 48-hour waiting period.

But soon he started saying he didn’t want her to get the abortion. He attempted to guilt and pressure her by saying this may be his last chance to have a baby and she was taking that from him (he was in his early thirties), saying she was “killing his child,” the texts show. He called her a “bitch” and an “asshole” and repeatedly asked her why she couldn’t just have the baby and let him keep it.

“I’m not a fucking breeder,” she recalls telling him.

She wanted to keep the pregnancy a secret, but he told many people around town, painting her as heartless. She felt like she was walking around with a scarlet letter around her neck.

Eventually his pleas and attention began to scare her. He frequently called her drunk, late into the night, until she picked up. He texted her endlessly even when she told him to leave her alone because she was sleeping or working. Over and over he texted her that they were connected forever because of this pregnancy and that she would regret the way she was treating him, though he insisted in the texts that these were not threats.

She started answering his phone calls out of fear that if she didn’t, he would show up at her house. Her roommate had moved out and she was living alone, which made her even more frightened. There were some times that she was “90% sure he was outside,” she said.

“I’m very against guns and everyone here is very Southern and always makes fun of me for it — they love them, they want to shoot them all the time,” A. told BuzzFeed News. “So my friend knew something was up when I told her that I wanted to get a gun to protect myself.”

“After this situation I’m like, how are people so pro-life?”

He made it clear to her that if she had the baby, he would force himself into her life, and said to her that he believed had more rights to the child than she did. She needed to get out of Mississippi and away from him and sever any connection between them.

Eventually she realized he was actively sabotaging her chance to get an abortion. He told her he was researching abortion laws in the surrounding states and knew the cutoff date for her to get an abortion, she said. The texts show that, despite this, he kept standing her up when they had arranged to go to the appointments, saying he had to postpone them again and again. Despite her sickness, on several occasions she drove herself to Little Rock to go to the clinic, only to find out he had lied about wiring the money to it.

“I wasn’t pro-life or pro-choice before this. I didn’t take a stance because I was very much like, you do what you need to do — if it’s not affecting me, I don’t care. If you want to dye your hair purple and run around naked, cool. I’m not gonna judge,” she said. “But after this situation I’m like, how are people so pro-life? You don’t know; it’s a situational thing. You can’t know until you are in this situation.”

By the time she realized he was never going to help her, she was too far along to scrounge the money together herself in time. In Arkansas, second-trimester abortions cost around $2,000 with sedation, and her family was dealing with a death in the family, grief, and medical bills related to other life-threatening health issues. She couldn’t ask them.

When she started desperately trying to take care of the abortion herself, all the barriers that make it hard for women in the South (and many other places in the US) became crystal clear to her. Abortion clinics closer than the one in Little Rock either didn’t return her calls or don’t sedate women during the abortion procedure. She was already obligated to pay $250 to the Little Rock clinic for the first consultation, mandated by state law, and didn’t want to have to do that somewhere else.

She started selling her possessions, her electronics, clothes, and furniture, but it still wasn’t enough. Weeks passed. Finals came and went, and the school allowed her to walk in the ceremony even though the events of the past few months had prevented her from fulfilling the requirements to graduate.

“My goal was, I cannot be pregnant when I walk across that stage. I’ve been working so hard for this, it’s a huge deal for me and my family,” A. said. “That is the one part of this that still makes me sad. I hate him for making me get to the point where I had to walk across that stage pregnant.”

Then, finally, she found the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund, an abortion fund based in Jackson, that pays for anything that will help women access abortion in the South. She got on the phone with the head of the fund, Laurie Bertram Roberts, and they instantly clicked. She stayed on the phone for three hours.

“Until I found them, I was preparing to have a child, with no desire to do it,” A. said. “It wasn’t until I talked to … Laurie on the phone and she said to me, ‘No matter what, until this is taken care of, we’ve got you,’ that I realized I had to stop saying to myself, ‘OK, I’m just gonna have to have a kid.’

“I had no options,” she continued. “I was literally like, do I just start drinking bleach? What am I gonna do? I just want my life back.”

Roberts’s partner drove two of her daughters who work as abortion doulas for the fund from Jackson to pick A. up and take her to Little Rock to finally get the abortion. But when she got there, it turned out the clinic had gotten the date of her last period wrong: She wasn’t 18 weeks from her last period, she was 20 weeks from her last period, which required a more elaborate, two-day procedure. She had to return the following week, but if she missed that appointment, that was it.

A. is not alone in experiencing these barriers to obtaining an abortion. A study from a reproductive rights research group affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, found that many patients who had abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy did so in part due to logistical delays, “including difficulty finding a provider and raising funds for the procedure and travel costs,” the study said. It also found that most women seeking abortions around 20 weeks were often “in conflict with a male partner or experiencing domestic violence.”

The morning of the final trip, they were running nearly two hours late. The rain was beating down on the windshield, and the cars on the highway had slowed to a crawl. Arkansas was experiencing historic rains that had overwhelmed the river’s levees, flooded several towns and farmlands, and caused crashes on the highways that brought them to a near standstill. The driver was chain-smoking Newports and cursing at the cars around them. A. felt sick.

When they finally pulled into the clinic, two middle-aged protesters were standing outside, one with a sign reading, “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you. —God.” A clinic escort in a rainbow vest with a rainbow umbrella came and escorted A. and her doula inside, checking them in with the armed security guard at the clinic door.

The clinic was entirely beige with framed impressionist paintings of flowers hung around the hallways. A door to a nurse’s office was open, and one wall was covered in a collage of magazine cutouts of male celebrities, like Idris Elba and Kit Harington, some with googly eyes stuck in suggestive places. A sign hung over the front desk reading, “A good man can make you feel strong, full of energy, and able to take on the world. No sorry, that’s coffee! Coffee does all that.”

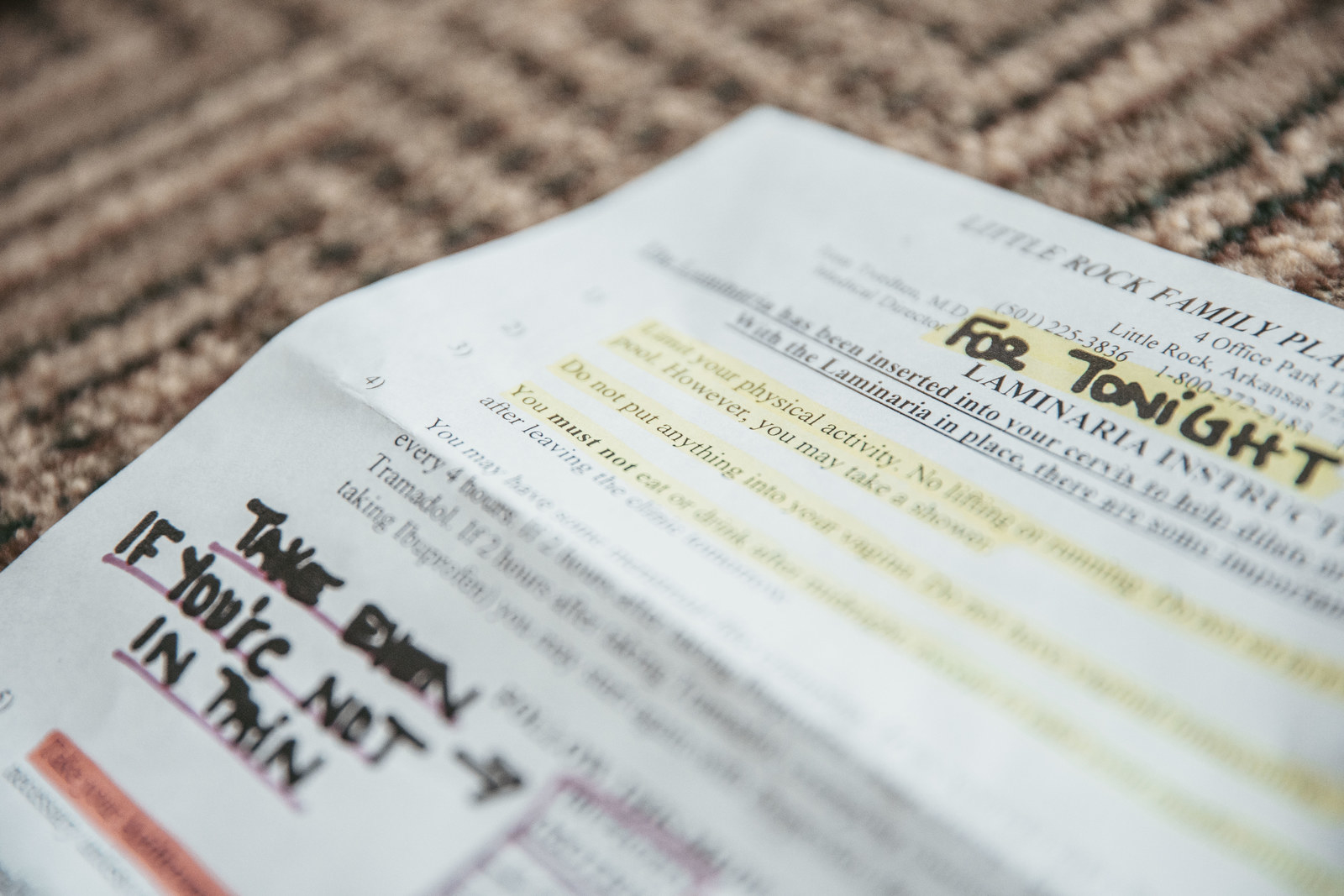

The clinic workers called her “lamb” and told her to lay back. They inserted matchstick-like pieces of seaweed into her cervix called laminaria, which, overnight, would expand and help “soften and open” the cervix, the head of the clinic, Lori Williams, told BuzzFeed News. They handed her a complex sheet of instructions detailing her medication schedule and the dos and don’ts for the night before the procedure. (Do: Take a lot of ibuprofen. Don’t: Eat or drink anything after midnight, get in a hot tub, or have sex.) The clinic worker covered the sheet in different-colored highlights and small handwritten notes to help A. understand it, then handed her a stack of diaper-sized menstrual pads and a plastic sheet, in case her water broke. That night, all she had were rainbow Tic Tacs and painkillers.

She woke up “feeling like death.” She had deep circles under her eyes and her skin had taken on a sallow yellow sheen. On the way to the clinic she was doubled over, with her head pressed against the seat in front of her, her hair being tangled by the wind coming through the open windows, barely able to talk and taking deep breaths. The pain grew more intense and she started sweating, feeling like she was going to pass out or vomit or both. The 22-year-old abortion doula from the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund, Sarah Roberts, rubbed her back and told her it was almost over.

It finally hit her: She wasn’t going to have the baby.

Just a few hours after she had stumbled into the clinic, the procedure was over. She had finally had the abortion.

“Let’s get a drink!” A. shouted to Sarah Roberts and her sister Aolani Jefferson as she came bounding out of the clinic and into the fund’s car.

The abortion was over and she was strangely euphoric. She was chatty and cracking jokes and wanted to listen to music. Back at the hotel, she sat on the floor and put on makeup in the mirror for the first time in days, then realized she hadn’t eaten since 9 the night before and she was starving. A. and her abortion doulas walked to a nearby Mexican restaurant to get tacos and margaritas.

“I am never going to regret doing this.”

“I feel amazing; I think I’m just on a high of like, I won. I did it,” A. said, shaking a bit too much salt onto her avocados. “I want to celebrate. I want to have a baby shower but a, like, my life shower. I can start my internship, I can leave Mississippi; I’m honestly riding on air right now.”

She slurped her margarita and felt a distance from the self who was pregnant just a few hours before. She started reflecting and thinking about her future. The color crept back to her face and her contagious smile reappeared.

At the next table, two mothers sat down holding newborn babies. A. stopped eating and stared at them.

“I’m looking at those babies right now and I should feel bad, but I don’t,” A. said. “I just want to hold them. I want to have one; I’ve wanted to be a mother since I was 9 years old. I’ve always worked with kids; it’s what I do and what I want to do, but right now I just feel relief. I am never going to regret doing this.”

She shook herself out of it and took another sip of her drink.

“This is never going to be something I regret; like, after the shit I went through, I know how strong I am,” A. said, her bubbliness fading slightly. “This is the first time in five months that I’ve had control over my life, starting now. It’s me now, it’s not anyone else.”

Sarah and Aolani raised their glasses. “To your life!” they said.

“Thanks,” she responded. “I’m gonna need a nap.” ●