Sometime in July, I got COVID and exiled myself to my basement for six days. I periodically emerged for food, or a few minutes in the backyard, but for the most part I stuck to isolation. My only companions were bottles of Gatorade and Paramount+’s hit TV show Yellowstone. Over five days, I watched the four available seasons.

Yellowstone follows John Dutton, played by a gruff and grave Kevin Costner, a sixth-generation Montana rancher desperately trying to fend off the forces threatening to take the titular ranch — be it the city slicker gentrifiers, the neighboring (fictional) Native American tribe, or the various elements of government. On the sixth day, I anxiously started the series again. I’d noticed that, more than any other show on television, its politics were working on me without me ever being open to them. Somehow, by the time I finished a season of Yellowstone, I found myself just a little more libertarian than I ever thought I would be. How does this show do that? What mechanisms does it use to pull off this magic trick?

It may not be television’s best show, but because of its extraordinary popularity, there is little doubt that it is America’s most important drama right now.

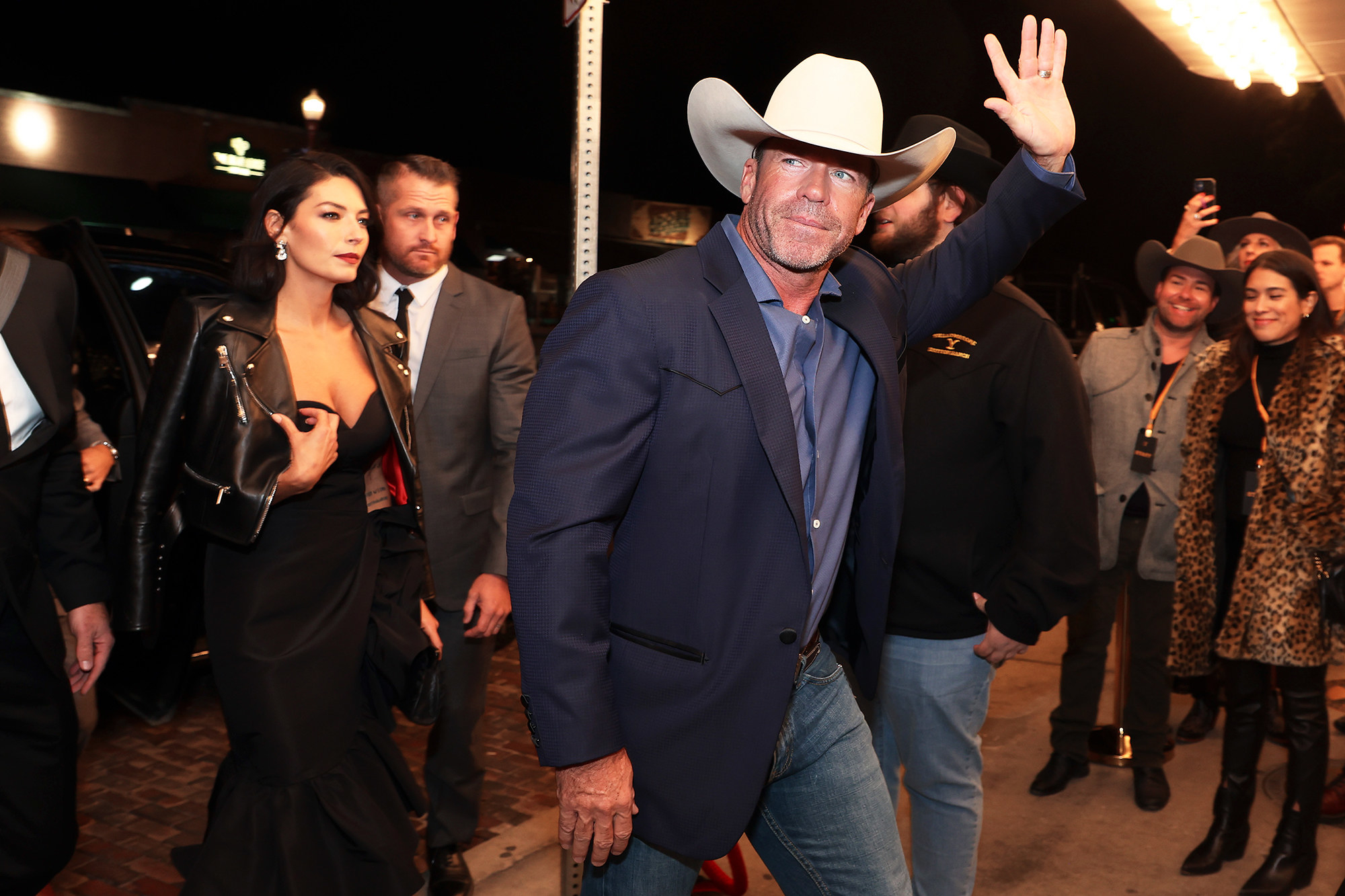

Yellowstone only debuted in the summer of 2018, but it’s already outdated to call it a mere TV show. The vast and ever-expanding world, helmed by creator Taylor Sheridan, can now be considered a proper universe. (Indeed, the folks at Paramount refer to something called The “Taylorverse.”) A prequel series, Yellowstone 1883, aired last year, while its follow-up, Yellowstone 1923, arrives in December. Spinoff 6666 will debut next year, and we’re already in spinoff-of-a-prequel territory: Bass Reeves, a spinoff from 1883, is due next year as well.

In its relatively short existence, Yellowstone has become America’s most-watched TV show — last week’s Season 5 premiere averaged 16 million viewers, making it the most-watched TV show of this year and the highest cable season premiere since The Walking Dead in 2017. Its popularity has jumped significantly since Season 4 ended, and specifically, its popularity jumped 60% among younger audiences. Numbers like these once befuddled the tiny but loud crowd of people whose job it is to write about TV on the internet, but we’re thankfully past the stage of being surprised at Yellowstone’s popularity.

Yellowstone features a whole raft of significant social tensions and myths crashing against each other. It may not be television’s best show, but because of its extraordinary popularity and its willingness to play with the existential crises over land, identity, and power, there is little doubt that it is America’s most important drama right now.

Yellowstone is occasionally described as HBO’s Succession on a ranch, but given the disparity in viewership numbers, perhaps it would be more fitting to flip that and say Succession is Yellowstone in a boardroom. The two TV shows can’t help but be compared — both debuted in 2018, and both concern a curmudgeonly powerful patriarch searching for a worthy heir to lead an institution that also represents a family legacy. But Succession’s most-watched episodes earn a fraction of the typical Yellowstone audience.

The comparison also falls short when it comes to acclaim — Succession has bagged a staggering 48 Emmy nominations (so far!) in its life and took the Outstanding Drama trophy twice. Yellowstone has a single nomination, in a category called “Outstanding Production Design For Narrative Contemporary Program (One hour or more),” an award category that sounds like I just invented it.

In Succession or Billions or the rest of the other prestige rivalry dramas, the goal is to unseat. Logan Roy’s enemies seek to become him, to seize what he has. What makes Yellowstone compelling is that John Dutton’s enemies are trying to make his way of life obsolete. The tensions in these shows may be similar, but in Yellowstone, the stakes are more existential.

In Yellowstone, the stakes are more existential.

John is the owner of the Yellowstone Dutton Ranch, the largest ranch in Montana. He is regularly besieged by forces threatening to break up his ranch. His enemies are numerous — Native Americans from the fictional Broken Rock tribe, as well as tanned developers who see the land’s vast tourism potential.

To fend them off, John mercilessly uses all tools at his disposal, conveniently represented by his three surviving children: there’s Beth (Kelly Reilly), who knows how to ratfuck executives in the language of business; Jamie (Wes Bentley), who does the same using the levers of the law; and the youngest, Kayce (Luke Grimes), a former Army vet and through-and-through cowboy skeptical of his family’s power while still doing his father’s bidding. John barely tolerates Beth’s methods and detests Jamie for starting to resemble those in the halls of government. He reserves more of his love for Kayce. Out of the whole Dutton clan, Kayce appears to be the one most connected to living with the land. If Yellowstone is King Lear, Kayce is Cordelia with confirmed kills.

While the Yellowstone ranch is threatened on multiple fronts, the show confers legitimacy to some of those threats while highlighting disdain for others. The weekend cowboys, hedge fund managers, and academics who see Montana as a place to gentrify are Yellowstone’s main enemies. In lengthy diatribes, the Dutton family takes turns admonishing these outsiders.

By contrast, Yellowstone makes significant effort to imbue the tussle over land with the Native American tribe with complexity. No one is “right” in Sheridan’s portrayal of this tension, and the show connects the Duttons and the Native Americans quite literally: Kayce is married to Monica (Kelsey Asbille), the daughter of a Broken Rock elder, and for significant portions of the show they prefer to live on the reservation, away from the Dutton trappings of wealth. Even as John ruthlessly pushes against the tribe’s advances, he has a grudging respect for their claim to the land.

Concurrent with the Dutton house drama is the drama of the ranch bunkhouse, where the ranch hands live. Yellowstone sees the bunkhouse as the path to an honest day’s work — its staff are the ones who make the ranch work. In one story arc, Jamie falls out of favor with his family, and his stint at the bunkhouse is what begins his redemption. The bunkhouse is also the primary site of one of Yellowstone’s most compelling character developments — young rancher Jimmy (Jefferson White) comes to the ranch as a lost fuckup unfamiliar with having to earn a living. By Season 4, Jimmy is transformed into a proper cowboy. The bunkhouse values are competence and independence above all else.

It’s hard to conclude that Yellowstone sees John Dutton as a hero, or even an anti-hero. Yellowstone shows clearly that these people murder and undermine people far too much for them to be worth rooting for morally. The drama portrays John as rapidly losing touch with how to keep his ranch — over the show’s evolution, he gradually makes riskier and riskier decisions, forcing him to mobilize more of his family and his workforce to clean up his messes. And even as he fights for the ranch’s future, John is increasingly cruel to all his children. But is the series about heroes? Or about the unrelenting cruelty of reality?

Despite the sprawling TV empire, the most direct analogy for Taylor Sheridan’s work is not Shonda Rhimes or Dick Wolf. Sheridan is not the white Tyler Perry, either. The closest comparison point for Sheridan is West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin. In both of their conceptions, personal events are meant to illustrate relationships to institutions.

Sheridan’s shows’ desire to subvert institutions is as strong as Sorkin’s desire to reinforce them: In Yellowstone, the Duttons see government offices, the law, and the state as dials to manipulate in service of keeping the ranch; in Sorkin’s shows, from West Wing to The Newsroom, Sorkin writes impassioned arguments for the state, for the media, for the Constitution itself. Sheridan seeks ambivalence, while Sorkin is after reverence. Both use the same instrument to play radically different tunes.

Yellowstone’s fourth season ends with John Dutton issuing what can be understood as a thesis statement for the show. When a powerful corporation seeks to put an airport in the middle of his land, John responds by running for the governor’s office. In his announcement speech, he stoically announces that “there is a war being waged against our way of life. That is progress in today’s world.” Then, a warning: “If it’s progress you want, then don’t vote for me. I am the opposite of progress. I am the wall it bashes against. And I will not be the one who breaks.”

By the time the fifth season premieres, we see that the message has worked: Dutton is indeed the new governor. Deeply unconcerned by the way a traditional politician is supposed to operate, John issues a number of edicts meant to punish the people who see Montana as a second home or a vacation rental. When his eldest son, Jamie, objects by saying some of his dad’s policies will set the state back by 30 years, Beth retorts, “That’s a good start, the plan is to set it back a hundred.”

Sheridan has scoffed at the conception of Yellowstone as a “red state Succession,” and he’s right to do so. If Yellowstone is conservative, its conservatism is not a modern-day conservatism: Republicans are obsessed with identity politics and the free market. Yellowstone is explicitly anti-capitalist — the Duttons regularly turn down unfathomable sums of money and opportunities to become even richer. The show has a solid environmentalist bent, even if it occasionally condescends to the environmental movement (one subplot makes fun of animal welfare protesters for not understanding the intimate relationship between ranchers and animal welfare).

Yellowstone also does not shy away from supporting its Native characters in their goals of self-liberation. Kayce’s wife, Monica, takes an active role in baiting the white men preying on Native women; Chief Thomas Rainwater (Gil Birmingham) wants the land back, and is willing to do what he needs to get it. The show has been praised for its three-dimensional representations of Native Americans in story (if not necessarily in casting). There’s plenty of room in the Dutton version of Montana for Black cowboys and both good and evil Native Americans. Racial diversity is not a threat in the Montana of Yellowstone.

Whether Yellowstone is a “conservative” show or not isn’t a particularly interesting question. The push and pull over who owns land and who is trying to take it away, and what the land is for, is as urgent today as it was 200 years ago, and Yellowstone explores that deftly.

The real threats are the outsiders who want to change the land. In the show’s pilot, on a routine visit to an ice cream shop, Kayce tells his son that the transplants “sure can make ice cream.” When the child asks what a transplant is, Kayce grimly replies, “It’s a person who moves to a place, and then they try to make that place just like the place they left.” For the young boy, this doesn’t compute. “That don’t make sense,” he replies. “Not one bit,” Kayce affirms.

John Dutton insists, almost pathologically, that the world is simple. He tells this repeatedly to his children, to his enemies, to his ranch hands. That modern society has overcomplicated things is one of Yellowstone’s central offerings. It all comes down to two things: the land, and the work.

Season 5 of Yellowstone sees John doing things he never thought he’d do in order to keep the ranch intact. He’s uncomfortable with performing the duties of the governor’s office — he doesn’t want to travel, doesn’t want to glad hand. None of the typical trappings of power appeal to him. When he’s presented with an early challenge, he considers moving in a direction that may see the Yellowstone ranch taken from him and put in a trust. For the children, this is worrying. But John is willing to do it if it means keeping the land intact.

Watching Yellowstone, I am regularly surprised at how much I am moved by a rich man’s plight to hold on to his ranch. But then again, Yellowstone manages to reframe several ideas in ways I didn’t expect. A group of ranch hands undergo the gruesome process of having the Yellowstone “Y” branded on their body as a test of loyalty. It makes for gory viewing, but Yellowstone is also able to twist this horrid image into a badge of honor.

The future of the Dutton family is central to the Yellowstone plot, but Sheridan is not entirely sympathetic to their success. Instead, Yellowstone is invested in presenting their conflict over land as eternal and moral, the most fundamental battle. Yellowstone’s biggest accomplishment is rendering this enduring dispute with urgency and clarity. ●