I hear it from friends all the time: “When will it go back to the way it was before?” And I get it. Six months into the coronavirus pandemic, I, too, hate it here. The deaths keep increasing, the cases keep surging and swelling, and it’s all hard to watch. But those rising tallies are a background hum to the main noise, a shrieking in my brain resisting change. I hate it here. I don’t know how to smile at strangers from behind a mask; I keep forgetting sidewalks and escalators now come with “keep right” instructions; I don’t know if it’s rude to hold the door for someone behind me or if I should just let it shut in their face. Everything is in flux, and nothing is settled.

On the best of days, I hate it a lot, and I feel the knot in my stomach pulling back to Before. And, rationally, I know things weren’t great Before. The earth was already warming to historic levels. Everyone I know was still burned out and just trying to survive. But Before was familiar. Before was navigable. It was a hell we knew. Now, the future of the pandemic stretches before us, unfamiliar and unknowable.

The rupture was sudden and the grief for shattered realities that we can’t properly mourn is unyielding. In the face of such a rupture, you have two choices: You could either desperately search to go back to Before, or search for a new way to do...everything.

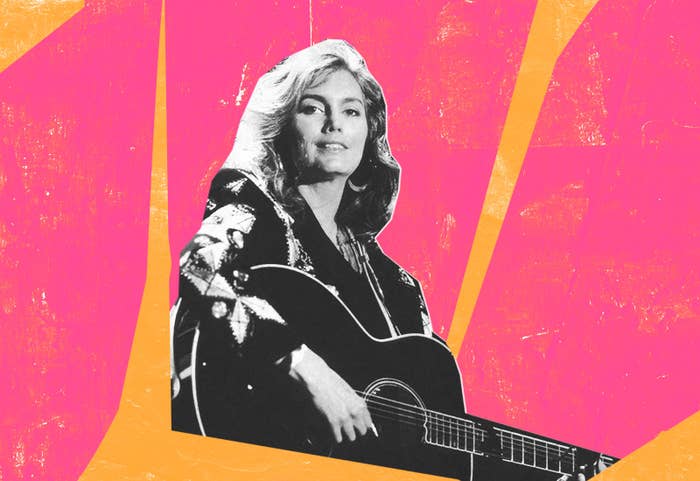

I’ve been thinking about ruptures this week as country legend Emmylou Harris’s masterpiece Wrecking Ball turns 25. Harris didn’t experience anything as dramatic as a global pandemic when she was making Wrecking Ball, but in the early 1990s she was adrift. She was in her late forties, and the country music establishment didn’t quite know what to do with her. Radio mostly had room for the big stadium sounds of a Garth Brooks, and less room for the traditionalists like Harris.

Harris left Warner, her major label, and went to an independent label. No one would’ve blamed her if she'd taken a bow and comfortably stepped into the “best-of compilations” stage of her career. Her new label made a play for country radio — 1993’s Cowgirl’s Prayer — but it didn’t work. She told the LA Times, “Country radio was not interested in me — I was too old, or whatever.”

With a new freedom to untether herself from her past, Harris turned firmly toward the unknown, searching for a new way to do…everything. She wandered beyond the bounds of the classic sounds that made her famous, beyond the expectations of a country artist widely seen as in the twilight of her career. At 48, with her eighteenth album, Harris redefined what a career-redefining album means.

Wrecking Ball was a departure from Harris’s history, but it wasn’t a betrayal of it — just a recognition that it wasn’t serving her anymore. Perhaps this is why I’ve been taking Wrecking Ball with me for long walks in the pandemic nights, walks that run double, triple its 53-minute runtime so I can keep living in it, again and again. I’ve been inhabiting this album during the pandemic, feeling the unbearable tug of resisting change but leaning on Harris’s steady voice. We’re both uncertain of what’s to come, but we’re sure as hell that we can’t go back.

The first thing you notice about Wrecking Ball is its sparseness. This is no accident — Harris handpicked Daniel Lanois to produce the record, and his trademark sound is all over it. The producer best known for working with U2 imbues everything he touches with what’s been labeled a “shimmer” effect — he makes vast sounds and draws your attention to the spaces between the notes.

These spaces between the notes are where you might find the divine dappling through. You get lost in those spaces. They are also the spaces through which Harris’s voice floats like a dream. Country music writers were suddenly resorting to words like “atmospheric” to describe what they’re hearing.

I feel the knot in my stomach pulling back to Before. And, rationally, I know things weren’t great Before.

This is not to say the country music establishment embraced the record — country radio mostly ignored it. It was as if it said: Stay in your lane, and do what we expect of you. And it was a hell of a lane that Harris occupied — for 17 albums and three decades before Wrecking Ball, she had earned the status of country royalty.

Harris can write — she cowrote “Boulder to Birmingham,” and she never has to prove herself in the writing department ever again — but she built her name on her unmatched ability to interpret other people’s songs. From Townes Van Zandt to Dolly Parton, Harris cemented a legacy of transforming her voice into a canvas for a song’s emotions.

But after finding herself with a trio of albums that didn’t catch the attention of country radio, she looked to reinvent herself. And in the mid-’90s, Harris wasn’t the only one looking for reinvention. In ’94, after years of slumping record sales and fading status, Johnny Cash released American Recordings, an album produced by Rick Rubin. Who, at the time, was mostly famous for his work in rap and metal music. It was an unusual pairing, to say the least, but one that paid off big-time: Recordings reintroduced Cash to a younger audience through covers of the likes of Nick Lowe and Glenn Danzig.

In an interview with the LA Times, Harris spilled a bit on how she ventured outside the expected and chose to work with a producer most famous for working with U2 and Peter Gabriel: “It was what he did with Dylan on Oh Mercy which brought me back roaring back to Dylan. That record moved me so much — I loved the production, I loved the songs.”

The Lanois-produced Oh Mercy turned the tides for Bob Dylan, who had spent much of the ’80s receiving poor review after poor review. In the hands of Lanois, a 48-year-old musician/songwriter won over critics with an audacious record that pushed the boundaries of what a Dylan album could sound like. “Ring Them Bells,” the centerpiece of Oh Mercy, might make you believe in God.

The collaboration between Harris and Lanois resulted in the sublime. The pair assembled a song list, which included some of the greatest songwriters working at the time — Gillian Welch’s “Orphan Girl,” Julie Miller’s “All My Tears,” and Kate & Anna McGariggle’s “Goin’ Back to Harlan” among them. The title track was penned by Neil Young, who sang backing vocals. Harris had always been a genius curator of songs, and in this album, there was not one choice out of place.

Wrecking Ball is a musical feast. The drums alone sound like a symphony, rich enough to fill the room with their echoes. Beautiful guitars come to the forefront and then recede like waves crashing on the shore. The bass rumbles and rages. But the album is undoubtedly built around Harris’s voice.

There is not a voice in all of music as honest as Harris’s. It is raw and beautiful and intimate, so much so that it occasionally feels odd to refer to her by her last name when it feels like you know her so well. “Goodbye” may be Steve Earle’s song, but when she sings, “But I recall / All them nights down in Mexico / One place I may never go / In my life again,” you believe her aching pain.

Harris’s voice and its arresting truthfulness has always been her secret weapon. On Wrecking Ball, it’s made to be the star. On “Where Will I Be,” the album’s opener, she sounds tentative and searching. On “Deeper Well,” she wages a revolution with her voice as the music seethes and brashes around her. On her take on Dylan’s “Every Grain of Sand,” when she sings the line “In the fury of the moment / I can see the master’s hand / In every leaf that trembles / And every grain of sand,” you might think you’re overhearing a private prayer.

Harris puts on a master class in how to render yourself vulnerable and fragile and insist not to break.

Harris puts on a master class in how to render yourself vulnerable and fragile and insist not to break. The album is rightly seen as a transcendent achievement. Later, she told the Guardian that the album was a turning point that “got her musician juices flowing again. It was like putting dynamite to a logjam.”

The album transformed Harris’s career. A moment that could’ve easily, respectably been the graceful winding down of a titanic career instead became a rebirth. Wrecking Ball never did win over country radio, but its blend of folk, Americana, and country bowled critics over and introduced Harris to an alternative music audience hungry for rooted rock music, rock music that paid tribute to its ancestors.

Harris found the new audience she deserved amid an alternative music scene where women were making the most interesting music. Two summers later, she was invited to join the headliners’ stage of the all-woman festival Lilith Fair, cofounded by Sarah McLachlan. Among its headliners: Sheryl Crow, Fiona Apple, Indigo Girls, Jewel. As Chuck Sudo noted in 2014, in the wake of Wrecking Ball, Harris “became a godmother of sorts for the Lilith Fair crowd and female singer-songwriters finding critical and commercial success themselves.”

These days, I hear Wrecking Ball everywhere I go. I hear it in Brittany Howard’s spacious echoes in Jaime. It’s all over Brandi Carlile’s last album’s rich sound, so intimate that it sounds like she is singing only to you. In Billie Eilish, I hear Harris’s literacy in straining and breaking in her voice.

I sense it, too, in the risks Kacey Musgraves took with Golden Hour — the freedom to trust yourself and leap and not worry about whether they’ll call your music “country” or not.

Wrecking Ball has been keeping me company through the pandemic. It is my unwinding record, the soundtrack to my turning inward. It has served as witness and balm to my deepest anxieties about the world right now. Will my family be safe? How will the pandemic change my job? What happens if schools close again? Unanswerable questions ring around my head constantly, and Wrecking Ball is always there to greet them.

In April, author Arundhati Roy wrote a moving piece about the great unsettling brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. “Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to ‘normality’, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture,” Roy wrote. “But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.”

I think of the doomsday machine and the chaos of Before. If everything went back to “normal,” I would not have the questions that haunt me today. But it’s also clear that whatever we were on course for before the pandemic wasn’t good either. Everything is changing, and this liminal place is unsettling.

Twenty-five years later, Wrecking Ball is still an album for the unsettled. For those unsure of what’s to come but damn sure that Before wasn’t working. Harris’s voice, fragile and assured, lights the way. Its opening notes ask: Wouldn’t it be a tragedy to come out of all this unchanged? Wouldn’t it be a shame if you go through all this chaos, trying not to let it affect you? ●