Everything about W. Kamau Bell’s new four-part Showtime documentary about Bill Cosby feels laden with risk. For one, there’s that title: We Need to Talk About Cosby. This invitation is at once off-putting and exhausting. Do you feel particularly up for the task of Talking About Cosby, with all that entails? After all, Talking About Cosby has become a site of fracture and division, especially for Black people. There’s the physical safety risk to the filmmaker: Cosby fans have been known to threaten those who publicly criticize him. And then there’s the professional risk of touching an uncomfortable topic. Writing about it for Time magazine recently, Bell notes, “This docuseries feels like it could be the end of my career.”

The film ought to become the gold standard of public reckonings — a thoughtful and thorough look at a monster.

But the largest risk Bell takes is artistic. We Need to Talk About Cosby, which premiered last week at Sundance, features women telling harrowing stories of being drugged and assaulted by Cosby, while at the same time tracing the comedy giant’s groundbreaking career and how he managed to burrow his way into America’s consciousness. (Cosby was convicted of sexual assault, but his conviction was overturned after a court found prosecutors were bound by an agreement not to pursue charges; he denies all allegations.) This is a precarious balance, one that could easily be misconstrued as an attempt to salvage Cosby’s legacy by framing what he is being accused of in the larger context of a titanic career. But Bell walks a messy, delicate line, managing to acknowledge Cosby’s impact while arguing that we have a duty to recanvass his accomplishments for clues that Cosby was the monster he is accused of being. He found plenty.

Bell’s documentary weaves powerful accounts from Cosby’s accusers with poignant insights into his legacy from academics, journalists (including an interview with BuzzFeed News deputy editor Jamilah King), comedians, and legal experts. The film ought to become the gold standard of public reckonings — a thoughtful and thorough look at a monster, a tender and clear-eyed recognition of what he gave us, and an urgent plea to not lose sight of either, no matter how hard it is to look.

“I am a child of Bill Cosby,” Bell states in the introduction of the series. “I’m a Black man. I’m a stand-up comic. I was born in the ’70s. I was raised by Fat Albert, Picture Pages, The Cosby Show,” he says.

Given that we know Cosby is accused of drugging and sexually assaulting more than 60 women, it seems weird for Bell to identify as a “child of Cosby.” You still say that? Some viewers may find themselves asking this question with a raised eyebrow, especially after Bell says early on that he believes Cosby committed the crimes he is accused of. But Bell’s investment is necessary.

The central question of the series, Bell suggests, is: “What do we do about everything we knew about Bill Cosby, and what we know now?” It’s a matter of disharmony, a dearth of concordance: “We loved him for such a long time,” Bell says, that the accusations felt like “new information,” a sudden alteration to an image we know so well. So Bell begins the task of integrating the two dissonant ideas of who Cosby is.

The timeline dispels the notion that Cosby’s career highs were somehow a separate era from the intentional evil.

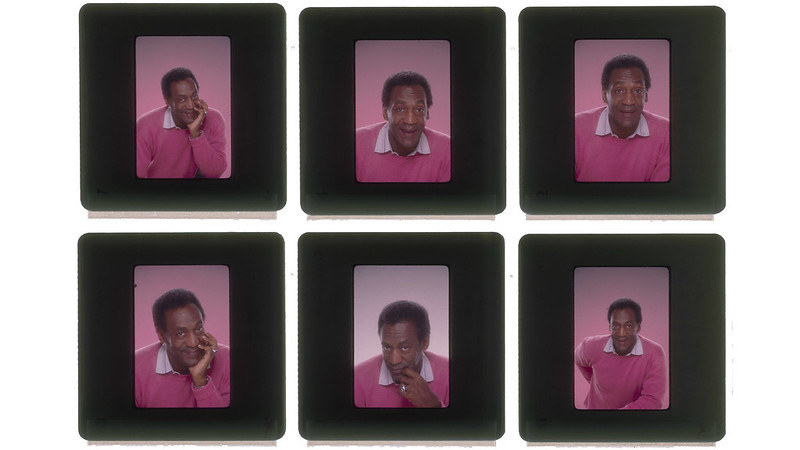

This schism is the engine of the series. To explore it meaningfully, Bell deploys a simple tool in a powerful manner: As he methodically charts the rise of Cosby as a clean comedian and bankable action star, all the way to the most powerful face on American television, an elegant timeline slots in the accusations Cosby faces during each phase of his career.

The effect is immediately devastating. The timeline dispels the notion that Cosby’s career highs were somehow a separate era from the intentional evil. The earliest story comes quite soon into Cosby’s rise, and from there, as Bell painstakingly chronicles Cosby’s growing influence, he carefully sews in the stories of Cosby’s accusers onto the chronological map.

Juxtaposing the two makes for an unsettling watch. In the first episode, Bell sheds light on Cosby’s powerful protest against using white stuntpeople in blackface, and how it directly opened the door for Black stunt performers. It’s a little-told story of how Cosby’s stance quite literally created an industry for Black people where none existed. But the act is quickly contrasted with one of the most harrowing tales of assault, which comes from Victoria Valentino.

In startling detail, Valentino tells the story of meeting Bill Cosby in 1969 shortly after her young son drowned. She says the comedian offered her and her friend pills, and under the pretense of driving them home brought them to a townhouse. Here, Bell’s camera is unflinching as Valentino recalls what Cosby did after drugging her: First, she says, he tried to rape her friend, and when she interrupted him, he raped her instead.

Then the examples pour in: Cosby was allegedly drugging women while making radical educational television like 1978’s Picture Pages; he was doing it while redefining stand-up comedy; he was doing it while he was starring in and running one of the most successful shows in the history of American television. Bell’s timeline serves to merge the two separate images of Cosby into one.

Beyond tracing these contradictory ideas, Bell excavates Cosby’s career to show what we had missed all along. When the talking heads react to footage of Cosby delivering his infamous “Spanish fly” routine, about spiking women’s drinks, we learn that he first told the bit in the 1960s and was still telling it in the ’90s (“Cosby, from almost day one, was telling us that he was willing to — and didn’t think anything was strange about — putting things in women’s drinks,” reacts academic Marc Lamont Hill).

Bell also plays his interview subjects a clip of The Cosby Show where Dr. Huxtable deviously explains how people “get all huggy-buggy” after eating his homemade barbecue sauce. Bell is in effect asking us to consider that perhaps Cosby has been giving us glimpses into who he has always been all along. It unsettles the notion that the Cosby story is some sort of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde tension. The New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb drives home the point: “You could make the case that it was all Mr. Hyde.”

Bell lovingly shows how transformative Cosby’s portrayal of Black love was. I found myself tearing up during a particularly moving sequence where Bell shows his guests the iconic Cosby Show scene where the Huxtables lip-synch Ray Charles’ “(Night Time Is) the Right Time.” Bell’s guests take turns expressing how much that scene meant to them, as Bell himself highlights the significance of the scene: Yes, we may hear a white audience laughing in the studio, but that scene is not for them. All the actors are facing away from the audience and turned toward Cliff Huxtable’s parents, a symbol of Black love, a tribute to older Black generations.

Elsewhere, guests come alive as they recall the theme song to Picture Pages, Cosby’s educational show for preschoolers. Or perhaps they find themselves still laughing at Cosby’s legendary dentist bit. But as the fond memories come rushing in, so does the horror of having to acknowledge that the person they had loved cannot be squared with what they have come to know about him.

The discomfort is the thing. Bell expertly highlights multiple dualities of Cosby. Yes, there is America’s Dad/America’s nightmare. But Bell also unearthed a special where Cosby is fiercely political and angry about racism, which runs directly counter to the dominant idea that he was a comedian who sought to avoid talking about race. We see him as a champion of young Black people, who funded scholars in HBCUs, juxtaposed with the moralizer-in-chief delivering the infamous pound cake speech. The man who championed Black people in writers rooms and directing chairs and makeup departments, set against the grouchy elder admonishing Wanda Sykes for how she speaks.

Through it all, the binding principle is Cosby’s ability to win America’s trust. The trust Cosby worked hard to win became his weapon: He used it to prey on women. In Bell’s documentary, women repeatedly tell stories of how their alleged assaults began with them trusting Cosby. Some of the women even introduced Cosby to friends and family, only to find that he had charmed them so thoroughly that the women had a difficult time getting their loved ones to believe them.

Toward the end of the documentary, Bell hits an unexpected roadblock: Just as he was about to wrap up filming with his guests, news broke that Cosby’s conviction was being overturned and the comedian will be released after three years in prison. We see Bell react with exasperation and disbelief — even if he had known where the project was headed, Cosby’s release complicates the ending and the story. “I don’t really know what this film is anymore,” Bell confesses. It’s an ending as untidy as the beginning — Cosby is free, but his reputation is in tatters. His alleged victims saw justice done, then undone. Those of us who loved and revered him for what he gave us now have to confront that it’s the same man who did so much damage. As one of Bell’s guests concludes, “He’s America’s Dad, but America’s dads have a rape problem.” None of the answers seem conclusive. Bell makes us confront that they were never going to be.●