You can trace my lineage when I speak Korean. My Korean teachers could hear the American in the rounded vowels and slurred consonants, and in the wild and lyrical intonations they could detect southern blood, and would ask, without fail, if my parents were from Gyeongsang-do, a province southeast of Seoul. For months, each of them tried — and failed — to drill the accent out of me and get me to mimic the Seoul accent: clipped, with a steady, almost monotone texture.

The first time I went to Seoul was about a decade ago. It was the beginning of summer, and I spent the first month holed up in a one-room down the hill from where I was taking Korean language classes. I was 23, and I had decided to come for the summer until I figured out what I was doing with my life. I was exhausted, but I didn’t know that then. What I knew was that I was depressed, and that I could not continue to live in San Francisco or New York or anywhere else in America so I might as well leave. All told, I ended up staying for almost three years.

The students I fell in with at the language institute were young, out of college, still in college, peripatetic men and women, some in a midlife crisis, others in a quarterlife one. We were lost, so we came here: half-Koreans, adoptees, one-and-a-half, second, and third generation Korean-Americans — gyopos — from Tulsa, Buenos Aires, Yokohama, Munich. We didn’t have much in common with one another, other than the fact that we were still figuring out our shit and nobody was in a rush to get a real job.

They were drinking friends, and I had a million of them.

We spent the day doing grammar exercises and our nights barhopping around Sinchon, a college neighborhood at the nexus of three major universities. At night the neon lights turned on and the pavement would be papered with flyers advertising kissing rooms and bottle specials. Drunk kids would take turns kicking padded soccer balls on the street. Usually we would start off at a barbecue place and get $3 servings of pork belly and soju, the national liquor that either tastes like sweet vodka or rubbing alcohol, depending on your mood. I learned a catalog of drinking games that started with either counting or pointing, but always ended with shots of soju perfunctorily plopped into mugs of cheap, clear beer.

We were lost so we came here.

I remember one winter night we went to this dimly lit bar in a half basement, where one of the girls was friends with the bartender, whom she called Justin oppa — older brother. Justin oppa practiced tricks, spinning empty tequila bottles around his long forearms and back. On special occasions, he would light a drink on fire.

A Korean-American girl, who had a face like a Cheshire cat but whose name I can’t remember, jerked her head and shouted, "Look at the LBHs!"

"What?" I asked.

"The LBHs!"

"What's that?" I shouted back. I followed her gaze to a table of four white men with fat stomachs and shit-eating grins. They had a familiar look in their eyes as they scanned the bar.

"What does that mean?" I asked.

"Losers Back Home!" She laughed. I threw my head back and laughed with her.

In that first year I took long walks around the city. I would get on the subway, a clean, almost noiseless contraption that hummed you to places. I let it take me to theater districts and street stalls, brightly lit cafés, galleries, and museums. I liked how I could slip into the scenery and stay still. The seasons sank into one another. For the first time it was quiet — there wasn’t that low-grade buzzing that happened when I would walk around a mall in Tampa or the streets of Brooklyn.

During the winter break in between quarters, I decided to work on an apple orchard. The farmer couple that ran it picked me up the night before to go camping underneath a magnificent sheath of ice, which they would climb with their friends. When we arrived at the campsite, some of their friends’ children had been eagerly awaiting “the foreigner,” and were appropriately disappointed when they saw me. “You’re not American!” they chirped. “You just studied in the States as an exchange student!” It is an odd sensation of displacement, when the narrative context is suddenly reversed: I was a foreigner who looked native.

After the children had been put to bed, the adults huddled around the fire, roasting pork belly and shooting soju from paper cups. “I know you were born in the United States,” one man said to me while chewing on a piece of gristle, “but you will always be Korean.”

I was a foreigner who looked native.

In the spring I joined a gay men’s tennis group, made up mostly of white collar workers in their thirties and forties, that met every Sunday around noon on clay courts on the north bank of the Han River. I was the youngest, the maknae, with a shoddy forehand but a curiously dependable backhand. We played tennis for five or six hours, sliding back and forth on the baked clay until our legs were streaked with orange dirt. Around sunset we would wash up at the faucets outside and then head to a restaurant and share big, satisfying pots of braised pork spine topped with crushed perilla seeds. Afterward, I would go to Jongno, a quiet neighborhood in the heart of Seoul for a second round at a pojangmacha, a drinking tent, with another one of the members, H, where we would drink until dawn.

The pojangmacha we went to reminded H of home: Jeju Island, a rocky crag off the southern coast of the peninsula where they have their own dialect and the women are famous for harvesting abalone and sea cucumbers from the ocean. The pojangmacha was one of many that lined the street: big red tarps with strings of light bulbs, a cart full of fresh seafood and meat, and plastic tables scattered around it. The ahjumma, a woman who moved from Jeju, had run the tent since the ’80s. She set up each day around 7 p.m., and packed up almost 12 hours later at the first signs of sunlight. She called me “Teacher” and him “Osaka,” because he had moved there when he was an adolescent. We saw our love for Korea reflected in each other — as a place of infinite missed possibilities.

The food was incredible. Everything was cooked to order — squid marinated in a vinegary red pepper sauce doused with sesame seeds, fish bursting with roe that you ate head to tail, and freshly steamed cockles. Sometimes she would tell you what to get. And always, she would fry up some eggs and give them to you on the side — even if you didn’t ask.

On some nights, if you were eyeing someone at a nearby table, you could tell her, and she would take a temperature of the situation and maybe urge all of you to sit together. If you were feeling morose about marriage pressures, she’d commiserate with a beer and give you advice. Sometimes she would tell you to make your parents happy and settle down, have kids. Forget about this life.

In the winter, she lit gas heaters, Velcroed the plastic sides, and weighed them down with jugs of water. Cold winds buffeted against the tarp, as steam collected on the plastic inside. Men came in groups of two, four, six, sometimes nine and ten, huddling around the little blue, plastic tables, raising their glasses to one another. Gay men who wanted nothing more than to be in the company of their kind, even for just a moment, to loosen the knots at their throats and say, let us drink to this and that and one another. I was there too, raising my glass and calling them older brother, friend, lover, until daybreak.

How can I describe what it feels like to be in a place where you belong?

It sounds like a sigh. It tastes like electricity.

It wasn’t until I had come out as gay and moved to New York City from Florida for college that I became sharply aware of my race — that I was Asian-American and therefore undesirable. I had imagined New York to be a gay utopia, but it was there, when I wanted to kiss someone or go on a date or went to gay clubs, that I felt it most. This rupture. A glass wall. Forever a spectator and never a participant. My last year in college, I discovered for the first time that I found another gay Asian man attractive. At a party, he told me that he liked my writing. I thanked him and told him I thought he was cute. “I don’t date other Asians,” he spat out, as though unspooling venom. I said nothing, because I understood that we had both internalized racism in ways beyond our understanding.

To come of age as a gay man in America necessitates identifying with whiteness and constantly measuring yourself against it. While overt racism of the “No fats, no femmes, no Asians” variety has (mostly) gone underground, it’s still the operating logic of desire even when there are no white men present. The real tragedy though is how it changes you: We shape ourselves around those expectations, whether it’s around the ideal — masculine, fit, wealthy — or around what they expect you to be: diminutive, pleasing, wanting. Sometimes you’re the exception, the one plucked out of the pile. The one not like the others. Both ways of being though, feel like states of disavowal.

To come of age as a gay man in America necessitates identifying with whiteness and constantly measuring yourself against it.

In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson writes about how she wishes she could imagine female sexuality that hadn’t been tainted by sexual violence. “I don’t even want to talk about ‘female sexuality’ until there is a control group,” she writes. “And there never will be.” In Seoul, that’s what I believed I could have. I was living in an alternate universe where I could imagine, scene by scene, a parallel history. In the spring, I would watch packs of high schoolers in their uniforms bombarding a fried chicken stand after school. I pictured myself among them, 16 years old, with dark navy pants growing short for my legs. He would have the childhood I believed I should have had. He would grow up confident — a bright young man. He would never question his place in the world, and would be utterly mystified if someone tried to explain that experiencing racism wasn’t just a slur, but also a feeling of isolation, in which you believe yourself to be ahistorical, a person without a people.

I believe the reason why so many Korean-Americans stay in Korea, long past when it’s good, is because that particularity of being a racial minority, which had been such a burden throughout our lives, had become a relative privilege. Seoul is a very easy place to live as an American. You can make a decent living teaching English; no experience required. A college degree, although pro forma, is easily avoided. Despite — or perhaps, because of — Korea’s recent history of utter destitution, it is a place where speaking English or being white still has real, material benefits. There lingers a strange mixture of awe and bitterness toward white people. Consequently, Seoul is a city filled with expats who do not necessarily love the city, but rather, love what it can do for them. They love who they can become.

I was living the life I thought I had missed out on, with all of its attendant fun, power, and pleasure. I was ravenous for it, and believed there would be no consequences. I drank. I was good at it and every night was an exhibition of will. Once I downed an entire bottle of soju in a single shot on a dare. You would be a good businessman here men said, slapping my back. I grinned and poured everyone another round and told them to drink. I invited myself to tables of strangers, and sometimes I slept with them. I flirted with women. I flirted with married men. I could be anything I wanted, because for the first time, I felt that I could.

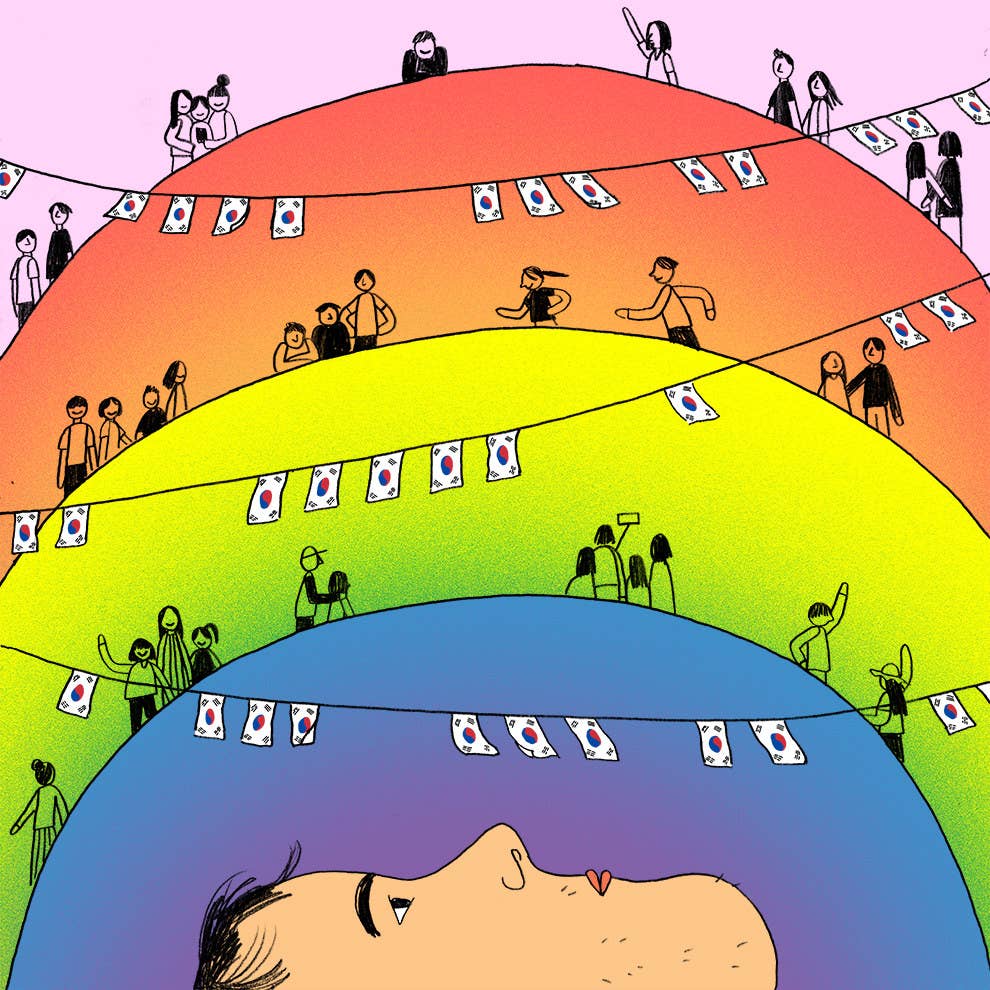

This life, too, was a masquerade. One gyopo friend from Texas said that Korea was like quicksand, and the more you struggled to leave, the more the country would suck you in. I felt that pull, how I could become lulled into this false sense of self. I was Korean-American, and felt I had to stake my claim back home in America. This was a moment to exist in the hyphenate, in the breath between two worlds.

I went back to Seoul again early this January on assignment to profile BTS, who had, without even trying, become the most successful K-pop group in America. On the weekend, I was at a loss over what to do with myself. I was so used to living in Seoul that I didn’t know how to pass through as a tourist. I went back to my favorite places and found that many of them were still there — the Korean-Japanese café with its beautiful wooden bar and fermentation projects, the barbecue pork place that sourced their meat from black pigs from Jeju Island, and the North Korean naengmyeon restaurant that made their buckwheat noodles from scratch.

Of course, I went back to the pojangmacha too, the one called Jeju Island, to see if it was still there. My friend warned me that the neighborhood of Jongno had changed rapidly in the past few years. The area had become trendy, and the hidden, sometimes seedy bars, had been replaced by sleek storefronts for expensive restaurants and tasteful boutiques. That Saturday night, straight couples crowded the tiny walkways in long coats waiting for tables and commenting on how they never knew such a cute place existed.

I was so used to living in Seoul that I didn’t know how to pass through as a tourist.

We got to the pojangmacha a little early. The ahjumma took a beat to remember me, but called me “Teacher” when she did. I told her she looked great, and she laughed that she had gotten a little tuck. I looked around at the tent, and everything looked the same, but the clientele had changed. It had become gentrified in all meanings of the word; it was a gay neighborhood that had receded a little further back into the closet. My friend told me that local business owners had formed a revitalization committee that deliberately kept gay people out. The transformation was stark and violent.

I got the cockles and the shishamo, and we quietly sipped on soju. It tasted like gasoline. I thought back to the last night I had spent in Seoul in this same pojangmacha, crying with friends over scallops and soju. It was the end of summer and the weather was cool and crisp like a melon split open. The ahjumma couldn’t believe that I was leaving. It was a slow night, and she was drunk after a few beers and burned our eggs and gave them to another table. She called me a bitch when I told her I was leaving for the States the next day.

There’s a Korean word jung that’s translated as “feeling,” “heart,” or “sentiment.” It has no English equivalent. The Chinese character has two parts: one that means heart, and the other that means the color blue or green, colors that have no distinction in Korean. It’s the color of youth. It’s the feeling you have when you meet someone for the first time, but remember them, as though from a past life, and it’s the thing that bunches up in your throat, day by day, so that when it disappears, it takes something of yourself. It’s the thing that makes you hold on when you should let go. Koreans often say that love is tragic, but jung is lethal.

The ahjumma demanded to know when I would come back to Korea. I didn’t know, I said, but I promised that I would. ●

E. Alex Jung is a staff writer at New York Magazine/Vulture.

This essay is part of a series of stories about travel.