Of course there was no way that Viet Thanh Nguyen could have known that just a week and a half before his new story collection The Refugees was published, President Donald Trump would issue an executive order temporarily banning refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries, and protests would erupt in cities across the country in opposition to the ban. But they did, and so Nguyen — whose 2015 novel The Sympathizer, about a Vietnamese spy who becomes a refugee in Los Angeles, won the Pulitzer Prize — has found himself having written the most timely short story collection in recent memory.

The stories in The Refugees — haunting and heart-wrenching, but also wry and unapologetic in their humanity — mostly tell the tales of Vietnamese refugees in the US, roughly from the late 1970s to the present. (A couple of stories take place in Vietnam.) A ghostwriter in her thirties is visited by the ghost of her teenage brother, who died at sea while the family was fleeing Vietnam. A young refugee gets taken in by a gay couple in San Francisco and has his own sexual awakening. A woman who’d escaped to the US with her mother visits her father and her half siblings in Vietnam. Throughout, Nguyen demonstrates the richness of the refugee experience, while also foregrounding the very real trauma that lies at its core — a trauma that is decidedly different from other immigrant stories.

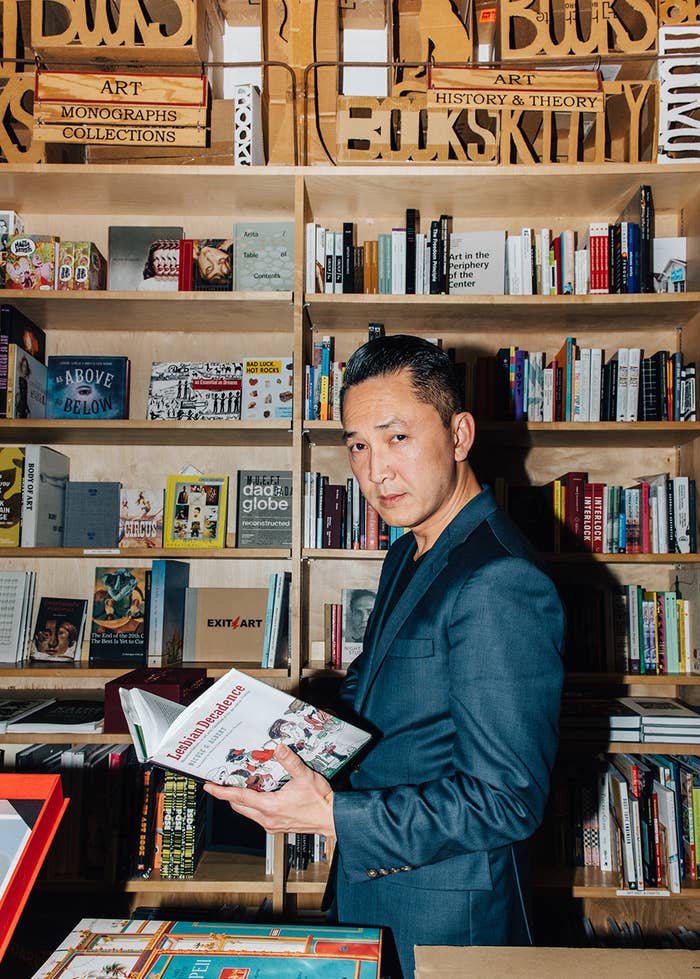

“The idea of the immigrant is so central to the American dream and the American mythology,” Nguyen said on a recent afternoon in his office at the University of Southern California, where he’s been a professor of English and American studies and ethnicity since 1997. His office is lined with books on shelves and in piles on the floor; a black-and-white poster of Miles Davis hangs behind his desk. “That idea of the immigrant as being part of an American story is so fundamentally strong that I was automatically being put into that story by reviewers and critics and so on. I had to actively say, ‘No, it’s not accurate.’ We need to understand how refugees are different so that we don’t erase the specificity of their experience.”

Nguyen, who is 45, was born in Buon Me Thuot, a city in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. When he was 4, in 1975, he and his family fled as South Vietnam fell to the North Vietnamese Army, and were settled by the US government in a refugee camp in Pennsylvania. As a child, he briefly spent time with two different American families — a period he has described as traumatic — before being reunited with his own family in Harrisburg. The Nguyens moved to San Jose, California, in 1978, where Viet’s parents opened a Vietnamese grocery that catered primarily to the refugee community there. Nguyen eventually graduated from UC Berkeley in 1992, where he also got a PhD in English in 1997. Besides his fiction, he’s published several well-received nonfiction books; his most recent, 2016’s Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, which he describes as a “companion” to The Sympathizer, was a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

The stories in The Refugees, which were written between 1997 and 2014, are not autobiographical, but they’re informed and influenced by Nguyen’s experiences. (In The New Yorker, Joyce Carol Oates wrote that Nguyen’s fiction is “pervaded by a shared intensity of vision, by stinging perceptions that drift like windblown ashes.”)

Nguyen is adamant that he's not writing for a white audience — that his stories and novel are speaking to Vietnamese people who instinctively understand the world his characters live in.

In one story, a young boy opens the door to a white stranger — something his mother has told him never to do — who robs them; an almost identical thing happened to Nguyen as a child. And throughout, there are breadcrumbs of details from The Sympathizer, like the song “I’d Love You to Want Me,” also the title of one story in this collection and the centerpiece of a pivotal scene in The Sympathizer, which was written after the stories in this collection. “In some ways, the narrator of The Sympathizer is someone who might have lived in the world of The Refugees, but on the margins,” Nguyen said.

Nguyen is adamant that he’s not writing for a white audience — that his stories and novel are speaking to Vietnamese people who instinctively understand the world his characters live in. “Therefore, I would not have to translate, and anybody who didn’t know what I was talking about would have to read more carefully and be more attentive,” he said. And particularly, when telling the stories of Vietnamese refugees and the Vietnam War, it is a world that is almost always mediated through the (usually white) American experience.

But when it came time to sell The Sympathizer, he found that the story wasn’t resonating in the way he'd hoped: On the day of the auction for his book, “13 or 14” publishers passed on it. “It was a horrible day,” he said. “I knew that the book was going to be bid on, hopefully, and then no bids came in through the entire day. So I had to sit there while the rejection notices came in, and by 2 or 3 p.m. our time, I thought, My god, my worst nightmare has been realized. I can’t sell this book. Then at the last minute, Grove [Atlantic] came through.”

Editorial departments at publishing companies are over 80% white. “It’s hard to read into why the book was not accepted, but I would imagine a lot of it has to do with this refusal to write a book that would be recognizable to the majority of editors in New York,” he said. “Some of these emails that I got — they didn’t say, ‘It’s because I didn’t get it,’ but I think someone said, ‘I couldn’t crawl into the voice.’ Another person said, ‘I got halfway, the book lost me.’ Stuff like that.”

Nguyen’s editor at Grove Atlantic, Peter Blackstock — who was only 26 when he bought The Sympathizer — said he was surprised to be the sole bidder. (The book received rapturous reviews; in the New York Times Book Review, Philip Caputo called it a "remarkable debut novel" and compared it to the work of Joseph Conrad, Graham Greene, and John le Carré.) “I thought that there would be an auction and, you know, maybe we get this or maybe someone would be able to offer a bit more money than we'd be able to and so we wouldn't be able to publish it. So it was obviously a great result for me.”

Nguyen sold The Refugees to Blackstock, along with a sequel to The Sympathizer called The Committed, which is still in progress. The original title of The Refugees was I’d Love You to Want Me, but Blackstock said that eventually the title didn’t seem quite right. “It’s a little challenging to remember a title that long,” he said. “So we came up with some other titles based on other stories in the collection. And then I said, ‘What about this idea of the refugees?’”

Nguyen’s wife, Lan Duong, is a fellow refugee and a professor at University of California, Riverside; they live in the LA neighborhood of Silver Lake, where they are raising their 3-year-old son, Ellison (named after Ralph Ellison). For them, the personal is inherently political. “We do try to talk to him in a somewhat adult way by talking about politics when it becomes relevant,” Nguyen said. “We’ve already talked to him about genocide, and he knows the word ‘genocide.’ If you ask him, ‘What’s Thanksgiving?’ he’ll say, ‘Genocide.’ We taught him a word for Donald Trump. He will say the word. People will think I’m trying to indoctrinate a little 3-year-old, but I’m okay with that, because I think children are indoctrinated in every society from the moment they’re born, so if you don’t agree with that indoctrination, you have to begin counter-indoctrination at a young age as well, so we try to do that without overwhelming him.”

Nguyen is trying to teach his son Vietnamese, even though he’s “not great” at it himself: “I got him bilingual editions of Curious George and other classic literature, but he doesn’t want to read them, he thinks it’s work.” But keeping that part of his heritage alive for his son is crucial. “We teach him some basic words, and his pronunciation is actually really good. Teaching children about heritage in a country that doesn’t respect heritage, for the most part, is very challenging. We just have to keep chipping away at his resistance to that, just as my parents did to me. When I was young, they made me go to Vietnamese language school. I hated every moment of it — nevertheless, it made its imprint on me. It’s important to try to do your best to retain some sense of the language and the history and the culture.”

Nguyen’s parents, who still live in San Jose, are not readers of his work, which has not yet been translated into Vietnamese. “My parents can read some business documents in English, but they’re not reading literature in English,” he said. One time, though, he brought a Vietnamese translation of one of the stories in The Refugees, “The Other Man,” to his father. “It’s a story about a Vietnamese refugee who turns out to be gay when he makes it to San Francisco. I never heard from my dad again about that story, because my parents are devout Catholics and they’re conservative. So if they actually read my stuff, it might be shocking for them, given the politics and everything that the books deal with.” They have, however, read things about Nguyen. “I went home this past weekend and I gave my dad a couple of articles written in Vietnamese about me, and he was very happy to read those. They’re proud of me, of the nature of the accomplishment, but not necessarily of what I’ve written.”

Several of Nguyen's stories deal with the complicated relationships between refugees and their grown children.

Several of Nguyen’s stories deal with the complicated relationships between refugees and their grown children. In “I’d Love You to Want Me,” a woman whose professor husband has dementia and has started calling her by the name of another woman is visited by her grown son, who wants his mother to quit her part-time job so she can stay home and take care of their father. Nguyen writes:

“Vinh sounded nothing like the boy who, upon reaching his teenage years, had turned into someone his parents no longer knew, sneaking out of the house at night to be with his girlfriend, an American who painted her nails black and dyed her hair purple. The professor remedied the situation by nailing the windows shut, a problem Vinh solved by eloping soon after his graduation from Bolsa Grande High. ‘I’m in love,’ Vinh had screamed to his mother over the phone from Las Vegas. ‘But you wouldn’t know anything about that, would you?’ Sometimes Mrs. Khanh regretted ever telling him that her father had arranged her marriage.”

Mrs. Khanh also wonders if Vinh still remembers their escape from Vietnam on a fishing boat. “After the fourth day at sea, he and the rest of the children, bleached by the sun, were crying for water, even though there was none to offer but the sea’s. Nevertheless, she had washed their faces and combed their hair every morning, using salt water and spit. She was teaching them that decorum mattered even now, and that their mother’s fear wasn’t so strong that it could prevent her from loving them.”

“I grew up seeing what my parents had gone through,” Nguyen said. “I would in no way want [Ellison] to go through any of that, which means, unfortunately, that of course he’s going to change. Generationally he’s going to be a very different person. He will be a very assimilated Vietnamese-American for whom Santa Claus always brings gifts. It didn't happen for me — I didn’t have any toys when I was growing up — but I don’t want to deprive him. So he’s going to become a very different person. I don’t know what kind of a different person, but inevitably, he will be more of an American for the good and the bad than I could ever be.”