President Donald Trump was in New Hampshire on March 19 when he promoted executing big-time drug dealers and running a blitz of ads that “scare” teens from “going to drugs of any kind.”

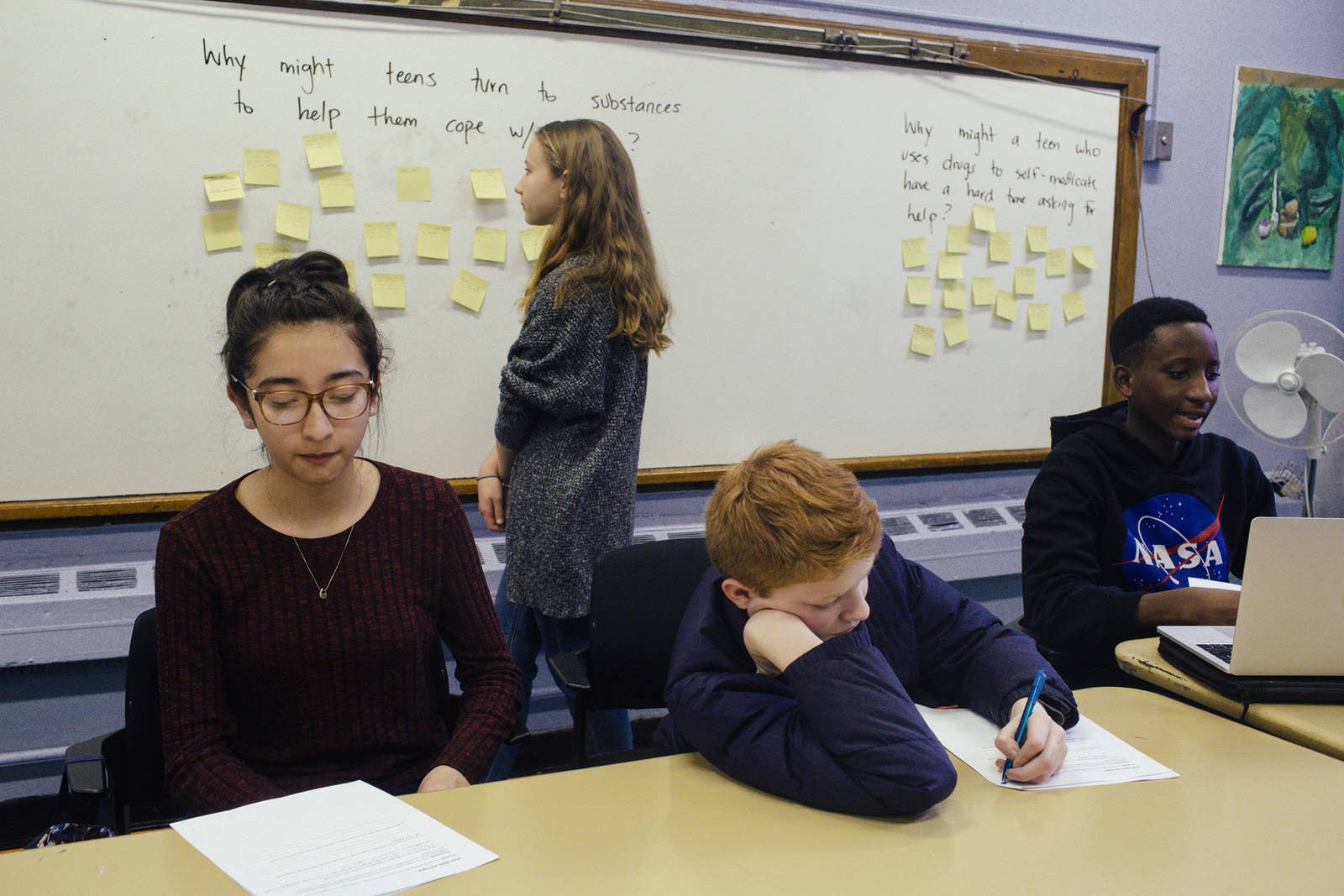

Eighteen hours after Trump's talk, 14 public school freshmen filtered into a classroom at Bard High School Early College on Manhattan's Lower East Side, where Drew Miller, a health teacher with a sex ed background, led them in totally different talk about drug use.

“If you’re choosing to use, make sure you’re in a good place, and with people you trust and a safe location,” Miller told the 14- and 15-year-olds, who are enrolled in a prototype drug course focused on making safer choices and reducing harm. “If you’re taking it, start with a small dose.”

Much of what is taught in the 14 sessions, which run 50 minutes each, may seem like common sense. But a dictum that doesn't demand abstinence is a fairly revolutionary act in American public schools, where anti-drug programs like D.A.R.E. have told kids for decades to "just say no."

“Why practice harm reduction?” Miller asked, referring to a central tenet of the course. It’s anchored on the idea that drugs cannot be eradicated completely, and that minimizing risk is best done through health services and education.

“Teens often find themselves in places where drugs are happening,” one girl offered. Several students yelled their ideas to cut risk: not taking any drugs, taking smaller doses, and not mixing substances.

The New York City Department of Education runs the course, but the curriculum was created by the Drug Policy Alliance, an advocacy group that supports medical treatment over criminal penalties for drugs and the legalization of marijuana. Trump’s war-on-drugs rhetoric is nothing new — trying to petrify kids into sobriety is a tactic that’s been used for decades. But there’s little scientific evidence teaching full abstinence from drugs works. The Drug Policy Alliance hopes this sort of drug class can be expanded, and that it could actually work.

New York state lawmakers in 2015 required schools to start providing “the most up-to-date, age appropriate information available regarding the misuse and abuse.” The Drug Policy Alliance responded by developing the class, “Safety First: Real Drug Education for Teens,” based on a pamphlet that the group wrote for parents. For schools, it combined instructional videos, homework, and free-wheeling conversations, all designed to meet the federal government’s National Health Education Standards.

Sasha Simon, who sits in on the classes to monitor their trial run, worked in sexual health education before starting at Drug Policy Alliance last year to launch the new classes.

“For once, somebody did it right,” she said after one of the sessions. “And I thought, I will push this as much as I can.”

Trump may actually like one aspect of the class — it does scare the kids.

Miller played a video about fentanyl and similar potent synthetic opioids, which are sometimes mixed into other drugs with fatal consequences. “It’s very easy to overdose,” a narrator in the video warned. “Carfentanyl is 10 times more powerful than morphine.”

“Oh my god,” a girl in class gasped. Two others clasped their hands over their mouths.

“I’d say you could die,” another student said about the advice she would give anyone considering opioids. “I’d say don’t do it — the harms can overtake the pleasure you get out of it.”

“If you give them the facts, they’re scary enough. You don’t need to say, ‘Don’t do it.’”

Simon reflected in the teachers lounge, “If you give them the facts, they’re scary enough. You don’t need to say, ‘Don’t do it.’”

But Trump has a different scare tactic in mind. As he said in New Hampshire, he wants to depict addicts in a state of depravity in order to “scare [kids] from ending up like the people in the commercials.”

Lewis Nelson, chair of the department of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, told BuzzFeed News that simply trying to scare kids into abstinence can have mixed results.

“Some children respond to scare tactics, but these can compel others to use,” he said. “Most people who hear that drugs can cause you to lose control, or even die, will avoid them. But some thrill seekers, or even just teens who believe they are invincible, may crave that sort of risk.”

“There is no magic bullet,” he added. “Although abstinence is optimal, we have learned in public health that this endpoint is only partially achievable. For those who use, harm reduction is essential.”

Harm reduction stands apart from Drug Abuse Resistance Education, D.A.R.E., a federally endorsed class that began in 1983. D.A.R.E. used to warn that pot would lead to crack, and still, it tells students to never try a drug. The medium is also the message: D.A.R.E. is taught by a cop. According to a 1998 study produced for the National Institute of Justice and presented to Congress, “D.A.R.E. does not work to reduce substance use.”

It remains the most prevalent drug education program in the US, reporting a budget of $10.3 million from private and public backers, with programs in all 50 states, reaching 75% of the country’s school districts. As criticism has mounted, D.A.R.E. has tried to adapt, and it reports that a new program for elementary schools, keepin’ it REAL, reduced marijuana, tobacco, and alcohol use by 32% to 44%.

Nelson isn’t opposed to D.A.R.E. and programs like it, he said. “They may work for certain students, but they need to be paired with harm reduction efforts for those who do not respond to abstinence education.”

D.A.R.E. has taken a hard-line stance against marijuana legalization, warning that it leads to more use of marijuana and suggesting that, in turn, leads to hard drugs.

Richard Mahan, D.A.R.E.’s chief operating officer, told BuzzFeed News his program does not teach complete abstinence, per se.

However, Mahan declined to share any current D.A.R.E. curriculum with BuzzFeed News, instead describing it as “state-of-the-art prevention science that focuses on providing students skills for safe and healthy decision making.”

If students were to ask, he wrote by email, “We respond by stating directly that students should never use illicit/illegal drugs of any kind.

It’s difficult for Americans to agree on what “works” in drug education, partly because they have different ideas about what qualifies as “working.”

The federal government’s Monitoring the Future Survey, which asks students in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades questions about their habits, has become the standard model to measure teen drug behavior. It asks when students try drugs for the first time and how often they use them. If officials say the results look good, they generally mean kids are avoiding new drugs and using them less often.

It’s difficult to agree on what “works” in drug education because Americans have different ideas about what qualifies as “working.”

The 1998 study for Congress about D.A.R.E. used metrics like these. It concluded classes that provide information, arouse fear, make a moral appeal, or build self-esteem, are all “largely ineffective for reducing substance use.” Rather, it found that teaching skills to resist social pressure “do reduce substance use. But the effects of even these programs are small and short-lived in the absence of continued instruction.”

Not surprisingly, researchers have different ideas about how to measure the success of the program at Bard High School.

Simon believes that asking about how behaviors changed during the course is “not important,” she said. “I think that what’s most important is that we are making sure young people are safe, not that we are preventing their use.”

Better metrics are whether students understand concepts like dose and dosage, considering their mindset and setting, and ability to keep each other safe, Simon added. She was also interested in the longer-term outcomes of creating adults who know how to avoid abusive habits.

“I don’t need to ask a teenager and make them feel uncomfortable,” she said. “I don’t need to ask a teacher to ask their student what drugs are you taking and how often.”

Indeed, at one point, Miller asked the students to not turn in a drug questionnaire they’d been given.

“You don’t have to do that,” he said as a class wrapped up. “It’s asking about your habits. If I collect it, and you report that you are doing something, I would have to — I would be concerned and have to talk to you.”

But Nina Rose Fischer, an assistant professor at City University of New York who is studying the class, thinks questions about drug use serve to understand the class’s impact. She’s comparing the cohort in at Bard in Manhattan to a control group at another public high school in Queens, where students are taking a more standardized health class. Her survey asks about drug use patterns before and after the class.

“We say how many times per day do you smoke weed, when do you smoke weed during the week?” said Fischer, whose research, which is also being funded by the Drug Policy Alliance, will be synthesized in a report.

She said students may divulge that they smoked pot during school before the course, but after the curriculum, they may report they’re only using it over the weekend. “And that,” she said, “would be seen as a harm reduction achievement.”

Some parents were alarmed by the Drug Policy Alliance’s stance on pot laws, Simon said. “I’ve gotten pushback from parents who are like, ‘What are you talking about with my kids? I know you are trying to legalize this. Are you trying to influence our kids to do that?’”

“We would not encourage drug use — we would never teach them to use a drug,” she said. “We give them tools to figure things out for themselves, which is much more important than to 'just say no.'”

But the legality of drugs — the risk of punishment, both under school rules and criminal law in particular — comes up regularly.

“If we were to legalize marijuana,” one of the girls volunteered, “it would be safer because people would know what’s in it. With legalization, people are less likely to put something into your body that you’re not aware of.”

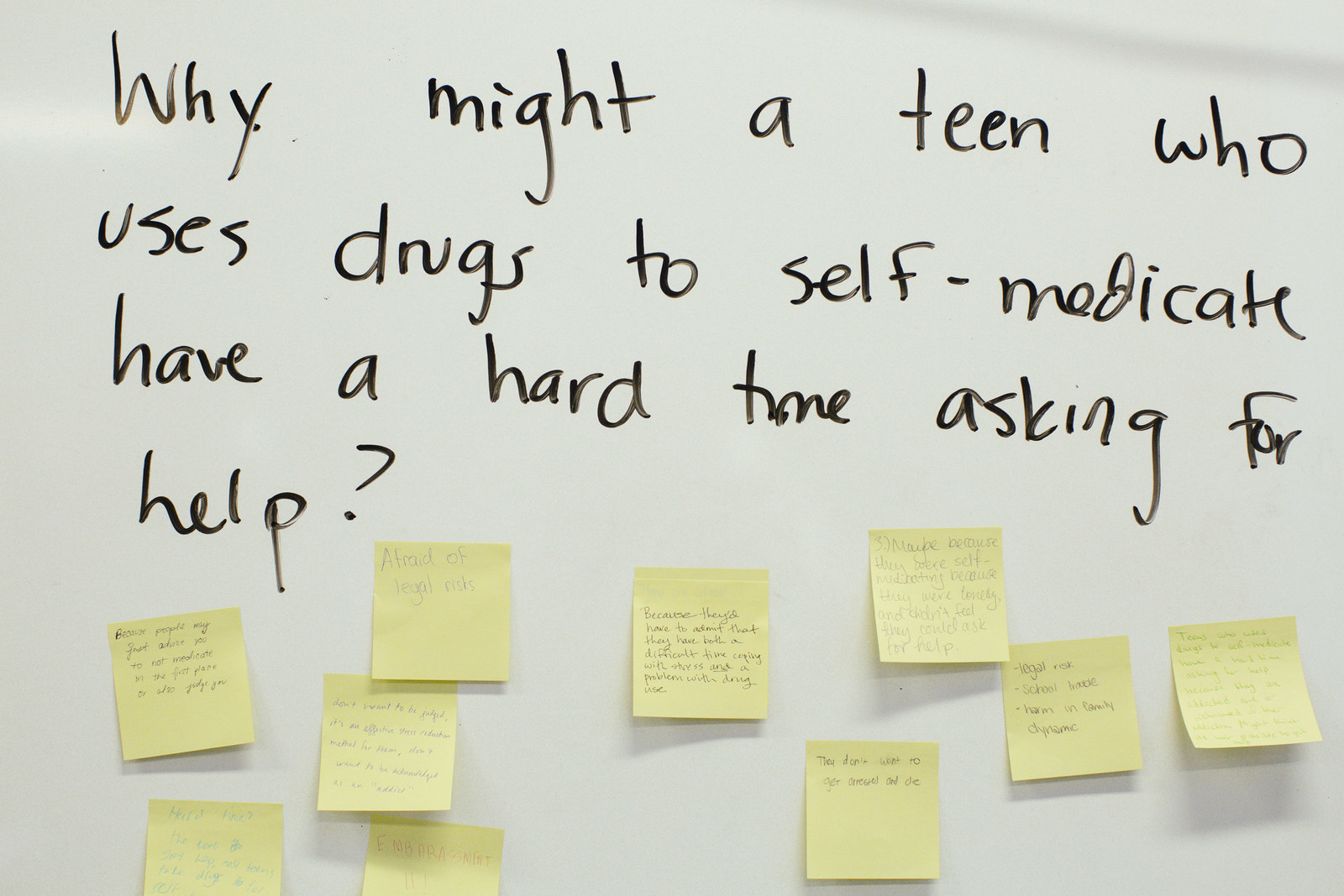

On Friday, March 23, the class talked about why people use drugs in the first place, and they debated the idea of “self-medicating” — that drugs can be used to relieve stress.

The conversation among the students straddled the line between possible benefits of drugs and alcohol — they can be fun and relieve stress — and the harms that can come of them. Rather than focusing overdoses and addiction, this particular discussion was about issues like a hangover or avoiding your problems.

“People might feel better in the moment, but it’s not long-term effective,” Miller warned.

Which is to say, the conversation reflected the sort of internal dialogue an adult might have with when deciding whether to order a third glass of wine and risk a hangover.

Or as one student put it, “It’s self-medication if it works briefly, but if it has longer-term repercussions, it increases the stress long-term.”