WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Monday issued its most sweeping decision ever to protect LGBTQ people from discrimination, finding that a federal ban on sex discrimination in workplaces also protects employees on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Despite same-sex couples winning the right to marry in 2015, firing workers for being LGBTQ has remained legal across much of the United States, since federal law does not specifically name sexual orientation or gender identity as protected classes, unlike race or national origin.

In a 6–3 decision, the court held that a federal law prohibiting workplace discrimination based on "sex" — Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — applied to cases involving LGBTQ workers.

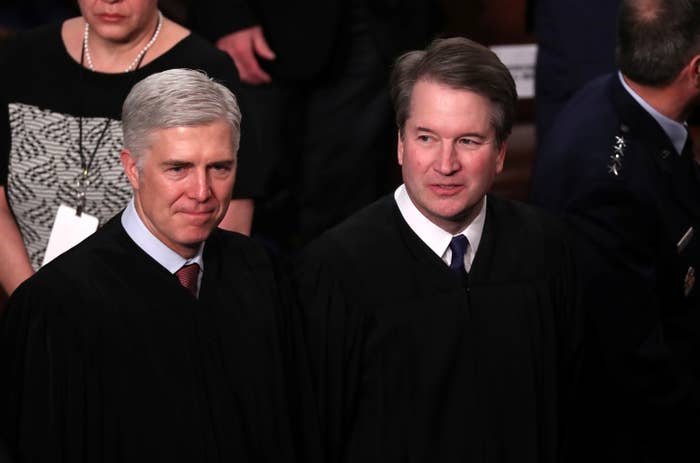

"Today, we must decide whether an employer can fire someone simply for being homosexual or transgender. The answer is clear," Justice Neil Gorsuch — one of President Donald Trump's two appointees to the court — wrote in the majority opinion.

"An employer who fires an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex. Sex plays a necessary and undisguisable role in the decision, exactly what Title VII forbids."

Monday's decision will have a ripple effect across the nation, particularly by banning workplace bias in dozens of the country’s Republican-controlled states, which never enacted state laws banning anti-LGBTQ discrimination.

The ACLU, which was part of the team of lawyers representing LGBTQ workers who sued after being fired, released a statement calling on Congress to update other federal civil rights laws that prohibit sex-based discrimination to make clear that those laws apply to LGBTQ individuals too.

"Our work is not done. There are still alarming gaps in federal civil rights laws that leave people — particularly Black and Brown LGBTQ people — open to discrimination in businesses open to the public and taxpayer-funded programs," James Esseks, director the ACLU's LGBTQ & HIV Project, said in a statement.

"Congress must affirm today’s decision and update our laws to ensure comprehensive and explicit protections for LGBTQ people and all people who face discrimination."

The Justice Department under Trump had argued against interpreting Title VII to apply to workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, reversing course from the Obama administration. Trump touted the confirmations of Gorsuch and Kavanaugh as a political win and a means of advancing a broad conservative agenda, which has included rolling back protections for LGBTQ people.

But Monday's decision highlights the fact that once judges and justices are confirmed to the federal bench, they enjoy lifetime tenure and are not beholden to the positions of the president who appointed them.

A Justice Department spokesperson did not immediately return a request for comment. Trump told reporters that he'd read the ruling and called it a "very powerful decision."

"I've read the decision, and some people were surprised but they've ruled and we live with their decision, that's what its all about," Trump said. "Very powerful. A very powerful decision actually. But they have so ruled," Trump said.

The decision comes just days after the Trump administration announced it was adopting a rule that would allow health providers to deny services to transgender people.

Democrats in Congress called on the Trump administration to update federal regulations to reflect the court's decision interpreting "sex"-based discrimination to apply to discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, including in the Affordable Care Act.

In a joint statement, House Judiciary Committee Chair Jerrold Nadler and Rep. Steve Cohen also urged the Senate to act on legislation already passed by the House that would update other civil rights laws that don't ban sex-based discrimination.

"[T]he forces against equality are still strong, and this Supreme Court decision is just one step on the path to LGBTQ equality," Nadler and Cohen said.

A spokesperson for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell did not immediately return a request for comment.

Title VII states that it's unlawful for employers to refuse to hire someone, to fire a worker, or to otherwise discriminate based on "race, color, religion, sex, or national origin."

Gorsuch wrote that Congress may not have been thinking about sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination when lawmakers included the term "sex" in that part of the Civil Rights Act, "[b]ut the limits of the drafters' imagination supply no reason to ignore the law's demands."

"The statute’s message for our cases is equally simple and momentous: An individual’s homosexuality or transgender status is not relevant to employment decisions," Gorsuch wrote. "That’s because it is impossible to discriminate against a person for being homosexual or transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex."

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan joined Gorsuch's decision. Justices Brett Kavanaugh — Trump's other appointee to the court — Samuel Alito Jr., and Clarence Thomas dissented.

Gorsuch rejected arguments by employers that as long as they treated all LGBTQ employees the same, it couldn't be "sex"-based discrimination. Employers had argued, for instance, that they could have a blanket policy of discriminating against LGBTQ people as long as they treated men and women the same.

But Gorsuch wrote that discrimination based on sexual orientation was ultimately about penalizing a man for being attracted to men and a woman for being attracted to women, and that gender identity discrimination was about punishing based on the sex they were identified with at birth.

"Any way you slice it, the employer intentionally refuses to hire applicants in part because of the affected individuals’ sex, even if it never learns any applicant’s sex," Gorsuch wrote.

Alito wrote in his dissent that Gorsuch had tried to present the majority's decision as in line with an approach to conservative legal decision-making known as textualism — rooting decisions in the text of the law and not other factors like legislative history or policy preferences — "but no one should be fooled."

Alito, joined by Thomas, wrote that a truly textualist approach would be based on what lawmakers understood the term "sex" to mean in 1964, and there was "not a shred of evidence" that Congress interpreted the term to refer to sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination at the time.

Alito wrote that he would allow employers to fire workers for being LGBTQ as long as the policy was applied equally to men and women. He rejected Gorsuch's contention that sexual orientation and gender identity were "inextricably bound up with sex."

Gorsuch was Trump's first Supreme Court nominee and had wide support from Republicans and conservative legal advocates; he replaced the late justice Antonin Scalia. Carrie Severino of the Judicial Crisis Network, which spent millions of dollars to support Gorsuch's nomination, tweeted in response to Monday's decision that "Justice Scalia would be disappointed that his successor has bungled texualism so badly today, for the sake of appealing to college campuses and editorial boards."

Kavanaugh, who asked just one question during arguments in the Title VII cases last fall, wrote a separate dissenting opinion that argued the majority's decision "usurps the role of Congress." He wrote that LGBTQ Americans could "take pride" in Monday's decision and praised their "extraordinary vision, tenacity, and grit," but he also disagreed with Gorsuch's interpretation of "sex."

"Instead of a hard-earned victory won through the democratic process, today’s victory is brought about by judicial dictate — judges latching on to a novel form of living literalism to rewrite ordinary meaning and remake American law," Kavanaugh wrote.

The Supreme Court’s decision stems from three cases that debate Title VII’s meaning — turning on the question of whether anti-LGBTQ discrimination is based on a person’s “sex.”

The first involves a woman fired from a Michigan funeral home for coming out as transgender. Aimee Stephens — who died May 12 — had presented as a man when she started her job in 2007 at R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes in Michigan. Six years later, after Stephens announced plans to wear women’s clothes, the owner, Thomas Rost, fired her.

In siding with Stephens, a 49-page opinion led by Judge Karen Nelson Moore of the US Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit found she raised a valid Title VII complaint: “The unrefuted facts show that the Funeral Home fired Stephens because she refused to abide by her employer’s stereotypical conception of her sex.”

Stephens' widow, Donna Stephens, said in a statement Monday that the ruling honored Stephens' legacy.

"My wife Aimee, was my soulmate. We were married for 20 years. For the last seven years of Aimee’s life, she rose as a leader who fought against discrimination against transgender people, starting when she was fired for coming out as a woman, despite her recent promotion at the time. I am grateful for this victory to honor the legacy of Aimee, and to ensure people are treated fairly regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity," Donna Stephens said.

Another one of the three cases before the court was Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, in which Gerald Bostock claims he was fired by the county for being gay. His Title VII claim had been dismissed by lower courts.

Bostock’s case was consolidated with a lawsuit filed by Donald Zarda, who sued his employer, Altitude Express, alleging the skydiving company terminated him for his sexual orientation in violation of Title VII. With support from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a federal agency that handles civil rights disputes, Zarda prevailed at the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals. The court found that a gay man wouldn't be targeted if he were instead a woman dating a man; thus he faced discrimination because of his sex.

"A woman who is subject to an adverse employment action because she is attracted to women would have been treated differently if she had been a man who was attracted to women," the majority wrote in an opinion led by Judge Robert Katzmann. "We can therefore conclude that sexual orientation is a function of sex and, by extension, sexual orientation discrimination is a subset of sex discrimination.”

Like other courts in Title VII cases, judges based pro-LGBTQ decisions in part on the landmark Supreme Court case Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins — a 1989 dispute in which a cisgender female employee claimed she wasn’t promoted because she didn’t appear feminine enough; the Supreme Court found that Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination also bans sex stereotyping in the workplace. Another key Supreme Court case cited by lower courts is Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., a 1998 case in which the Supreme Court found that Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination also prohibited workplace harassment in the case of a man who was perceived to be gay.

But in arguments last year, the Justice Department told the Supreme Court those older cases did not apply and sex discrimination cannot be construed broadly to include LGBTQ workers because, as a general matter, it is legal for sex-segregated rules to exist, such as restrooms and dress codes.

The issue of restrooms has been particularly thorny. During oral arguments in October 2018, several justices wondered what consequences ruling for Stephens would have on using bathrooms — such as transgender women using bathrooms that match their gender identity — as well as implications for women’s sports.

ACLU national legal director David Cole, who argued on behalf of transgender workers, said a bathroom or sports policy was not an immediate issue before the court. But he said forcing transgender people to use facilities that clash with their gender identity would "impose a discriminatory injury."

The Trump administration disagreed, arguing that sex discrimination occurs only when “similarly situated” individuals are treated differently — not comparing a gay or transgender person to a straight or cisgender person. For gay workers, the Justice Department said, “An employer who discriminates against employees in same-sex relationships thus does not violate Title VII as long as it treats men in same-sex relationships the same as women in same-sex relationships.”

Gorsuch dismissed the bathroom issue entirely, writing on Monday that the fight over Title VII was about workplace discrimination and not those other issues: "we do not purport to address bathrooms, locker rooms, or anything else of the kind."

Alito countered that Gorsuch was too casual in dismissing the effect of Monday's ruling on other areas of the law, including on issues like what bathrooms transgender people use and the many other federal laws that prohibit discrimination based on sex in areas such as healthcare, housing, and education.

"Although the Court does not want to think about the consequences of its decision, we will not be able to avoid those issues for long. The entire Federal Judiciary will be mired for years in disputes about the reach of the Court’s reasoning," Alito wrote.

Lawyers for Clayton County in the Bostock case argued that Congress had not intended to protect LGBTQ people under Title VII, saying that “the original public meaning of the term ‘sex’ at the time Congress adopted Title VII in 1964 was the trait of being male or female, not sexual orientation or homosexuality.”

The case for Stephens was brought in the name of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a largely autonomous federal agency that championed her cause. But once the case reached the Supreme Court, per typical procedure, the solicitor general at the Justice Department took over to represent the government.

In Stephens’ case, this meant government lawyers now argued it was legal to fire her — taking the opposite position as the EEOC even though it was representing the agency. LGBTQ advocacy lawyers stepped in to make her case.