Madonna is done talking about her age.

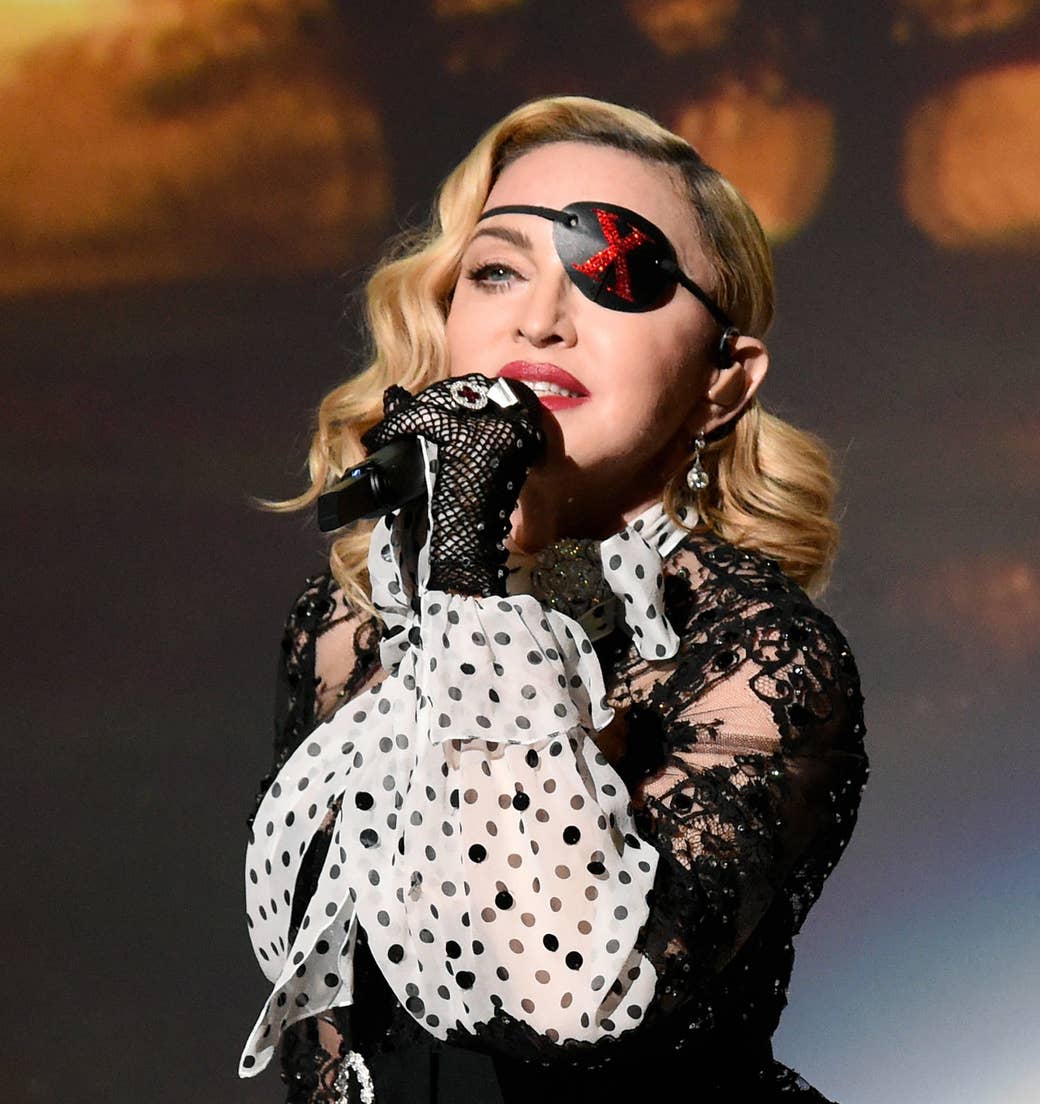

In the press cycle for her 14th studio album, Madame X, released last Friday, the pop icon has lamented “being punished for turning 60” to British Vogue and feeling “raped” by a New York Times Magazine profile’s “never ending comments about [her] age.”

Her anger, on the one hand, makes perfect sense. In the last 10 years, Madonna, who’s built a legacy on shredding societal norms, has often called out the media for its tireless astonishment at a woman still playing the pop game past her 50th birthday. We should take her art at face value, her frustration implies, and question why we’re so shocked by her mere continued existence.

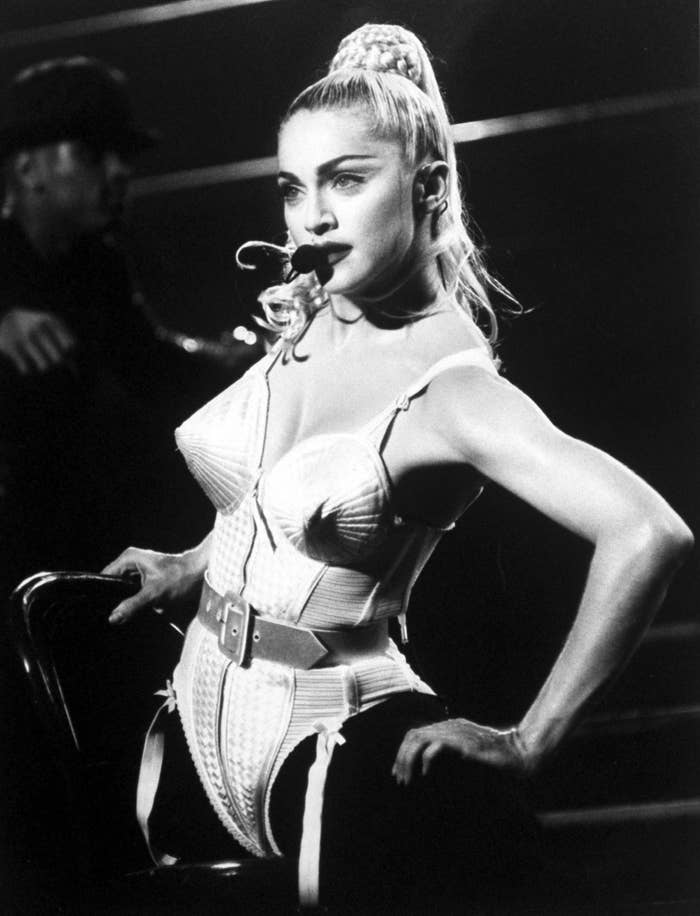

On the other hand, Madonna’s indignation is a little puzzling. This is capital-P Pop music, after all, a medium that justly or unjustly is about fetishizing youth — the heightened emotions, the horniness, the athletic live performances — and isolating the fickle tastes of a teen-skewing, music-consuming public. This is doubly so for women. It was true when a 25-year-old Madonna writhed around in a tattered wedding dress on MTV, electrifying teens, horrifying their parents, and blueprinting pop stardom as we know it. And it remains so this year, with the ascent of the 17-year-old goth pop phenom Billie Eilish. A 60-year-old pop performer is just not something you see a lot.

In fact, as one of just a handful of women pop artists who’ve maintained relevant pop careers deep into their thirties and beyond — Cher, Tina Turner, Janet Jackson, Kylie Minogue, Mariah Carey, and now Beyoncé among them — it actually feels wrong not to note Madonna’s age. It’s a crucial part of what makes her fascinating and exceptional in 2019.

Even more head-scratching, Madonna spent her late thirties and forties pioneering a mode of middle-aged pop stardom that flaunted maturity and leveraged honesty about aging to her advantage. From 1998’s masterpiece Ray of Light through 2005’s Confessions on a Dance Floor, Madonna made music that was proudly older and wiser while sacrificing none of the sex appeal or fun we often associate with pop.

It’s in the years since then — during a curious pivot over the past decade toward less idiosyncratic and, at least conceptually, more radio-friendly material engineered to compete with the Gagas and Arianas of the world — that Madonna’s career has stalled. Contrary to her protestations, while ageism may be part of what’s stymieing Madonna — and it’s worth noting that she’s had seven top 10 singles since her 40th birthday, a herculean achievement in pop — the thing that’s most certainly holding her back is music unbefitting and unreflective of her status as pop’s Doyenne Supreme.

Her new album, Madame X, ostensibly arrives as a reset, and it raises the question: Is Madonna’s problem the public’s fixation on her age? Or her resistance to talking about it?

When it comes to pop, maturity is a bad word. In its very DNA, pop is music for young people, made primarily by young people, and that’s been true at least since Elvis swiveled his hips on The Ed Sullivan Show. The most familiar pop, the kind on which an entire industry has churned for decades, is about baby love, dancing the night away, teenage dreams, and dying young, and not, for instance, intimate reckonings with motherhood.

But Madonna has proven herself a potent exception to that rule, a woman who will go down in history as much for her formidable catalog as she will for remaking pop culture in her image. And with Ray of Light, she pulled off her neatest trick yet.

Following her initial apex in the late ’80s, the singer’s ultra-lascivious 1992 album Erotica, released when she was 34, did drastically worse in sales than her previous album, 1989’s Like a Prayer. It was pegged as one of pop’s most infamous flops (no matter that it’s one of her very best albums). While she attempted to right the ship with 1994’s softer Bedtime Stories, by the middle of the decade all signs pointed to Madonna’s heyday being in the rearview mirror. And that wasn’t a huge surprise. She was a woman pop star in her mid thirties, and most of her former chart competitors — Cyndi Lauper, Paula Abdul, Taylor Dayne, Belinda Carlisle, and Debbie Gibson among them — had all experienced precipitous career declines.

But, ever the brazen chameleon, Madonna boldly switched tacks. On Ray of Light, she swapped the combative sexuality of Erotica and Stories for incisive introspection on her life as a 40-year-old mother. As she told Billboard at the time, “I feel like I’ve been enlightened, and that it’s my responsibility to share what I’ve learned so far with the world.” And she did.

Everything had indeed changed, and the public rewarded Madonna for being honest about it in her work.

Atop adventurous electronica from then-unknown producer William Orbit, Madonna sang about the birth of her first child, the isolation of her life as a globe-trotting superstar, and the sacrifices of fame that had come back to haunt her. She explored her discovery of yoga and kabbalah and selflessness, processed wounds from childhood, and unpacked intergenerational familial baggage from a decidedly adult perspective. “When I was very young, nothing really mattered to me but making myself happy,” she sang on the ethereal house anthem “Nothing Really Matters.” “Now that I am grown, everything’s changed.”

Ray of Light was a profoundly risky move for a pop star, asking her audience to ditch the teen-idol provocateur rolling around in the wedding dress or twisting her cone bra and instead embrace her exactly as she was then: a proudly middle-aged woman. As pop, it could have been a complete disaster. Instead, it sold 16 million copies, launched three top 10 singles, and earned Madonna her first and only Album of the Year Grammy nomination. Everything had indeed changed, and the public rewarded her for being honest about it in her work.

Light also gave Madonna’s career a second wind as pop’s reigning earth mother, able to compete on the charts with the Britneys and Christinas, less than half her age, but with music miles away from their featherweight teenybopper anthems. She followed that album with three more containing some of her finest hits, each treading the line between innovation, pop’s youthful inclinations, and the wisdom of maturity to (mostly) critical acclaim and commercial success.

By the time the last of these, 2005’s Confessions on a Dance Floor, arrived during Madonna’s 48th year, it felt like she’d defied gravity. She’d spent her forties, geriatric in pop years, proving there was a place for a middle-aged women pop stars who sang about being women and middle-aged. Dance Floor’s lead single “Hung Up” was a victory lap, a return to disco frivolity but with lyrics that explicitly took on her commitment to never looking backward. “Time goes by so slowly for those who wait,” she reflected, “no time to hesitate.” It became her 36th top 10 single.

While it’s true that pop consumers are often young and fickle, and stars can sometimes inhabit personas to great effect, our culture also rewards authenticity — access to the inner workings of our icons. That’s why it’s such a treat to hear 19-year-old Taylor Swift detail a crush, 22-year-old Kesha recount a debauched night, 25-year-old Ariana Grande on the dissolution of her first engagement, and 82-year-old Leonard Cohen’s pontifications on mortality.

Truth is intoxicating, and Madonna’s career rebirth in the late ’90s and early 2000s highlighted how baring it all could counteract the whims of even the most youth-ravenous, capricious industry around. The staying power of radical truth has been borne out in the careers of other aging women pop artists as well. Janet Jackson broke out at 19 with her seminal coming-of-age record, 1986’s Control, and had a more successful run in her thirties than most, thanks largely to her 1997 opus, The Velvet Rope. Rope, like Light, smartly wore wisdom on its sleeve and veered sharply from Jackson’s previous musical approach, with the 32-year-old largely abandoning the feel-good empowerment and playful sensuality of her earlier work.

Instead, she dug deep into depression, childhood trauma, the AIDS epidemic, and even the physical abuse she sustained at the hands of her ex-husband. It was edgy material for pop that succeeded because of — rather than in spite of — its unapologetic adultness, setting her apart from the teen pop stars who had followed in her wake. The Velvet Rope was a massive commercial success and is widely seen as one of the greatest pop releases of the ’90s.

But unlike Madonna, Jackson struggled mightily throughout her forties. She followed up Rope with a series of far lighter albums aligned more directly both with the pop of their moment, and then was dominated by her most fervent imitator, Britney Spears. (It should be noted that this period also coincided with the Super Bowl “wardrobe malfunction,” which had a huge and undue impact on Jackson’s career.) Jackson’s latest album, 2015’s Unbreakable, marked a return to introspection and generally chilled-out Grownness, and was not a commercial juggernaut. But it did succeed as a critical darling, helping to rejuvenate her image, restore public goodwill, launch a successful comeback tour and Vegas residency, and induct Jackson, now 53, into this year’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

More recently, Beyoncé, with both her self-titled visual album and especially 2016’s landmark Lemonade, gave her own career new life by ditching the trappings of mere pop stardom and embracing the role of pop music’s most profoundly candid matriarch. On Beyoncé, she dove headlong into the contours of her marriage to Jay-Z and established herself as the most audacious modern feminist in the industry. On Lemonade, she laid bare the depths of her pain as a mother experiencing punishing infidelity, tying her experience back to both her personal lineage and that of black women more generally.

Light, Rope, and Lemonade each dared to defy the notion that pop is purely about being young. To the contrary, they asked us to relish these women’s adultness — and the messiness, gray areas, growth, and, yes, sex appeal therein. Their makers, in turn, were fearless in their desire to keep it real and not to stoke the youth machine of the Popular Music Industrial Complex. And their audiences were more than willing to listen.

In the same Times Magazine profile that drew Madonna’s ire, Vanessa Grigoriadis observed that Madonna’s discography writ large has been “one long process of meaning-making, of understanding herself through her art.” It’s an important observation. Despite being known for remaking her image each album cycle, Madonna’s most indelible work has been about self-interrogation, whether that be around her Catholic faith, her abusive marriage to Sean Penn, or her willingness to come clean about life as a stroller-wielding, Downward-Dogging mommy. Little of that has been present on her last three albums.

Instead, 2008’s Hard Candy, 2012’s MDNA, and 2015’s Rebel Heart have been mired in anonymous trendiness. These albums mostly featured hotshot producers of the moment, like Timbaland on Candy and Diplo on Heart, and a Madonna dead set on either recalling her past glories or angling for the zeitgeist she once effortlessly created. Each has been a commercial and critical failure.

Madonna, then, has posited Madame X as another of her famous reinventions. She even created a new character for the record, the titular Madame who is “a secret agent traveling around the world. Changing identities. Bringing light to dark places. ... A dancer. A professor. A head of state. An equestrian. A prisoner. A student. A mother. A child. A teacher. A nun. A singer. A saint. A whore. And a spy in the house of love.” More enticing, Madonna enlisted Mirwais, producer of the excellent Ray of Light follow-up and sister album Music, to work behind the boards; she mentioned in an Instagram comment that she yearned for the days “when I made records with other artists from beginning to end and I was allowed to be a visionary.”

To her credit, Madame X is a return to brazen sonic experimentation. The production, handled by Mirwais along with Jason Evigan, Mike Dean, and others, is uniformly excellent and bizarre while maintaining the cohesion Heart sorely lacked. Together with Madonna, they’ve incorporated elements of dancehall, classical strings, reggaeton, Portuguese fado, hip-hop, Latin pop, Brazilian funk, and more into dark, dizzying whirls that shapeshift over each song’s runtime in thrilling ways — the lush disco beat that emerges halfway through “God Control” is a stunner.

Madonna is right. Pop, as a rule, is not always kind to older women. But her career is living proof that rules were made to be broken.

But while the character Madame X may be an entire litany of things, what’s wholly unclear from the album Madame X is who Madonna is in 2019. Much of the album’s lyrics trade in broad sociopolitical commentary, the brand of quote cards your liberal mom might have posted on Facebook during the Women’s March: “We came out of the dark / Everyone has a spark” and “Your future is bright / Just don’t turn off the light” on the Quavo-featuring “Future.” Or “Your world is such a shame / ’cause your world’s obsessed with fame” on “Dark Ballet.” Or “Lord have mercy / Things have got to change” on “Batuka.” What exactly needs to change, though, is never made clear.

When Madonna’s not sloganeering, she’s singing lovely but undistinguished ballads like “Crave,” a lilting Spotifycore tune that brings to mind Halsey’s “Without You.” Other times, she indulges in fun, if unnecessary, Latin-tinged dance tracks like “Faz Gostoso” and “Bitch I’m Loca,” passingly enjoyable but light in the way of artistic revelation. It’s never quite clear that any of these songs need to exist when we’ve already got pop landmarks like “Frozen“ and “La Isla Bonita” in the bank.

What’s missing once again, as with all her recent work, is Madonna herself — the woman, the mother of six, the 60-year-old who’s survived against all odds, the artist who more or less created the game and who is now being asked, once again, to blaze the trail forward for shamelessly older women in pop. An album that addressed these things would be groundbreaking, a perspective that only Madonna, just as she is right now, could add to the conversation. In its place, we have the sonic manifestation of her lashing out at the Times profile: music that feels defensive and guarded and even a little condescending, a middle finger to any fan who would very much like an update on Madonna’s life in her music.

Madonna is right. Pop, as a rule, is not always kind to older women. But her career is living proof that rules were made to be broken. And she need look no further than her own work to know that art that engages honestly with the self, at any age, can melt barriers and maybe, just maybe, put a sexagenarian icon who’s endured for almost 40 years back on top.

At the very least, it could make for some great pop music. Until she is ready to talk to us about being 60, though, we are stuck with a professor, a head of state, a child, a teacher, a singer, a saint, and a whore. What we don’t have are a ton of reasons to keep listening to Madonna. ●

DJ Louie XIV is a New York–based DJ, writer, and actor. Louie has been a fixture in New York nightlife for the past decade and spins regularly at New York City’s premiere venues and clubs, as well as in major cities across the country and world. His writing has appeared in Vanity Fair, BuzzFeed, and HuffPost.