Robin Hvidston held up an X-ray of a human skull pierced by a metal rod, clear across the eye sockets from temple to temple. Outraged gasps escaped from the small crowd.

“Please take note of this,” Hvidston said. “This picture was taken one day before graduation. One day. This is what happened to him.” She was reading a statement prepared for the occasion by Kathy Woods, mother of Steven Woods, the high school student whose skull was pictured in the X-ray. Steve was killed in 1993 on an Orange County beach after an altercation with another group of teenagers — as he and his friends tried to drive away, the other group pelted their cars with rocks, bottles, wood blocks, and a paint roller that crashed through Woods’ window and speared him through the head.

Kathy Woods learned later that several of the youths behind the attack were living illegally in the United States. “I stridently believed then, and I do to this day, that if the federal government would do their job as they’re mandated to do, and defend our borders, and keep American citizens safe, Steve — along with many, many other victims — would be alive today.”

Off to the side, leaning against a wall and listening, stood Maria Espinoza, founder and director of the Remembrance Project, and the person who arranged this late October press conference in Washington, D.C. For six years, Espinoza has been convening testimonies from the family members of people killed by illegal aliens — as they’re referred to in the law and, when they’re feeling polite, by most of the people in this room (other options included “invaders” and “illegals”).

Espinoza is a rising star in a constellation of activists belonging to the once marginalized anti-immigration right. Nativist sentiments have long existed on both the right and the left, based on the perception that undocumented immigrants harm American workers. But the rise of Donald Trump turned a spotlight on ideas that were once confined to the hardline fringe, particularly the conviction that immigrants are violent criminals. And Espinoza, whose group has worked directly with the Trump campaign, is a pioneer in a particularly effective form of advocacy based on that very premise: using the gut-wrenching stories of those whose family members have been killed by undocumented immigrants to push for more restrictions on immigration.

Espinoza is a rising star in a constellation of activists belonging tothe once marginalized anti-immigration right.

Although there is no conclusive data on the number of crimes committed by immigrants in the U.S., decades of research in various fields have consistently found that immigrants are less prone to crime than the native-born. But data is often less compelling than the harrowing personal stories Espinoza brings to bear.

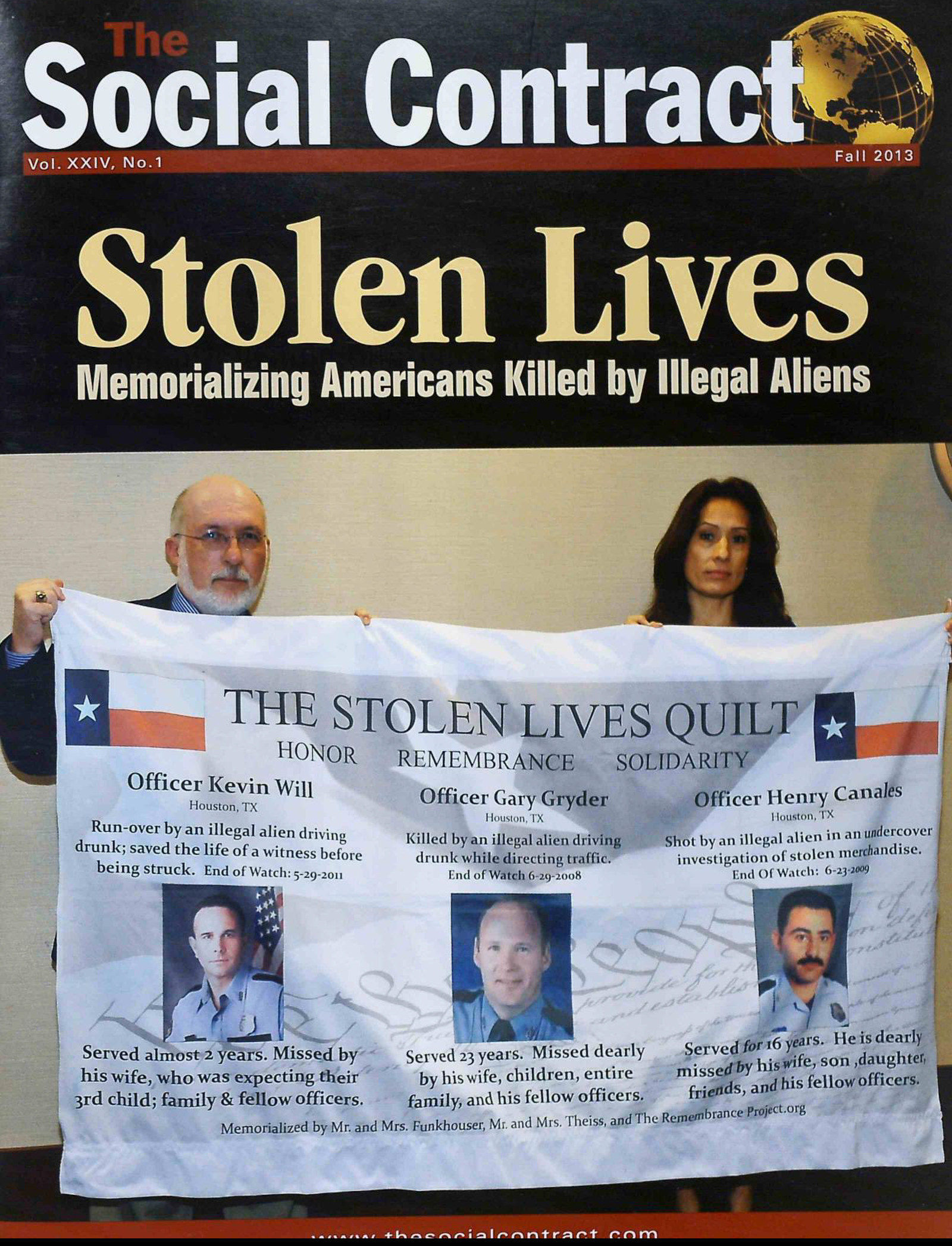

“No one is immune to the illegal who drives wildly drunk, or the wanna-be gang-banger who needs to machete innocent citizens to gain entry and respect into the Latino or other gangs,” Espinoza wrote in 2012, in a sort of mission statement published by The Social Contract, a quarterly journal founded by John Tanton, seen as the godfather of the modern anti-immigration movement. “We have uncovered the fact that Americans are under assault.”

After the press conference in Washington, I followed Espinoza and her group to the White House, where they intended to find a spot to camp out with their posters. She was accompanied by her husband, Tim Lyng, who co-founded the Remembrance Project and works as a civil engineer. Espinoza was loath to answer questions about herself. “I want you to talk about them,” she said, referring to the five families the Remembrance Project had flown in from around the country earlier that week. “I’m boring!”

Nevertheless, Espinoza shared that her father immigrated to Texas from Mexico in the 1950s, and that he “did it the right way.”

“He never looked back,” she said. “I never saw a Mexican flag anywhere — not in our home, you know? It was just America and the Bible.” Espinoza is 53, with sharp features and a practiced air of solemnity. The seed of her activist career, she said, was planted some 20 years ago in Houston, when she was working as a paralegal, divorced and raising her daughter alone. “I saw things taking place in the country that I just felt weren’t right,” she said. “I realized that people who weren’t working as hard were having a better life than I was.” She recalled how a relative, a World War II vet, had his monthly pension cut from $240 a month to $200 — “and yet there were people illegally in the country who got everything free.”

“And sadly, shamefully, I never did anything about it,” she said. “For years.”

In 2006, a Houston police officer named Rodney Johnson was shot and killed by Juan Jose Quintero, an immigrant from Mexico with a rap sheet that included a charge of indecency with a 12-year-old girl, for which he had been deported seven years prior. While sitting handcuffed in the back of a squad car, using a pistol the officer had missed in a pat-down, Quintero shot Johnson seven times.

In the ensuing years, conservative media outlets would point to Johnson’s murder as the first in a rash of killings: Four law enforcement officers in Houston died after him in shootings or car accidents involving undocumented immigrants. Espinoza told BuzzFeed News that these deaths are what finally spurred her to found the Remembrance Project in 2009. She made a full-time occupation out of tracking down crime victims, offering to advocate on their behalf, attending murder trials to show them her support, and eventually bringing them along on her travels.

This is how Espinoza amassed the network of grieving families that largely accounts for her current influence. They provided the names, faces, and death dates that Espinoza printed on a series of 3-by-6-foot banners — the “Stolen Lives Quilt,” the Remembrance Project’s signature visual prop. In 2012, Espinoza took the quilt on an inaugural tour of the country that included meetings with government representatives in 20 state capitals. She also helped popularize the idea, started by the Tea Party Immigration Coalition, of a “National Day of Remembrance” held every November to honor people killed by immigrants.

It was around this time that the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Anti-Defamation League, and the Center for New Community began tracking Espinoza’s connections to organizations they consider part of the white nationalist movement, many of them founded by John Tanton. The Social Contract, the journal that published Espinoza’s manifesto in 2012, is run by Wayne Lutton. According to the SPLC, Lutton has served on the editorial advisory board of the white nationalist Council of Conservative Citizens and regularly speaks at its conferences. (That group’s practice of tallying crimes committed by black people against white people is what, by his own admission, radicalized Dylann Roof, the perpetrator of the Charleston church shooting that killed nine black parishioners.)

In 2014, the Remembrance Project received a $25,000 donation from U.S. Inc., one of Tanton’s groups.

That same year, according to the Anti-Defamation League, Espinoza joined in on a “night watch” on the border organized by the Texas Border Volunteers, an armed vigilante group that splintered from the Minutemen and that, as the Texas Observer reported, based on the testimony of a former member who provided photographic evidence, “engages in aggressive armed interdiction and detention of immigrants using ATVs and trained dogs.” (Espinoza and the Texas Border Volunteers dispute this claim, describing the group’s activities as limited to “observe and report.”)

Asked about her affiliations with white nationalists, Espinoza said in an email: “I don’t consider anyone left or right… just for our families or against our families.” Later, she added: “Neither I nor my organization are ‘tied’ to white nationalist individuals or groups, and, as a Latina by ethnicity, I am not ‘white.’”

Espinoza rejects the term “restrictionist” and says the term “nativist” has been wrongfully appropriated by the “pro-amnesty crowd.” “The left ties these words to racism,” she wrote. “We tie [nativism] to preserving our American heritage, which is made impossible with mass illegal immigration. … All countries are ‘nativistic.’ The American left wants to enforce a standard of behavior that no other country enforces.”

“We are not anti-immigrant," Espinoza wrote. "We are against illegal aliens trespassing upon our soil.”

Espinoza has found allies among reliable immigration hardliners in political office, such as Republican Rep. Steve King of Iowa. (In 2011, King introduced a resolution to officially mark the National Day of Remembrance.) But her work otherwise went little-noticed outside right-wing circles. Her admirers see this as a symptom of the problem at hand: the willful blindness of the American political and media establishment to the ongoing criminal onslaught.

“It’s been a heroic effort on her part,” said Joe Guzzardi of Californians for Population Stabilization, a group that has received Tanton funding, according to the SPLC, and that frames its immigration restrictionism in terms of environmental preservation. “It takes a lot of courage and a lot of time to do these kinds of things. Because, you know, you’re really bucking up against it.”

Early in July, days after Donald Trump announced he was running for president, a 32-year-old woman named Kathryn Steinle was shot and killed while taking an evening walk with her father on a pier in San Francisco. The man who shot her was a convicted felon and five-time deportee from Mexico. Trump, having refused repeatedly to apologize for his comments referring to Mexican immigrants as criminals and “rapists,” was emboldened by Steinle’s murder. “This man — or this animal — that shot that wonderful, that beautiful woman in San Francisco, this guy was pushed back by Mexico,” Trump told CNN on July 9.

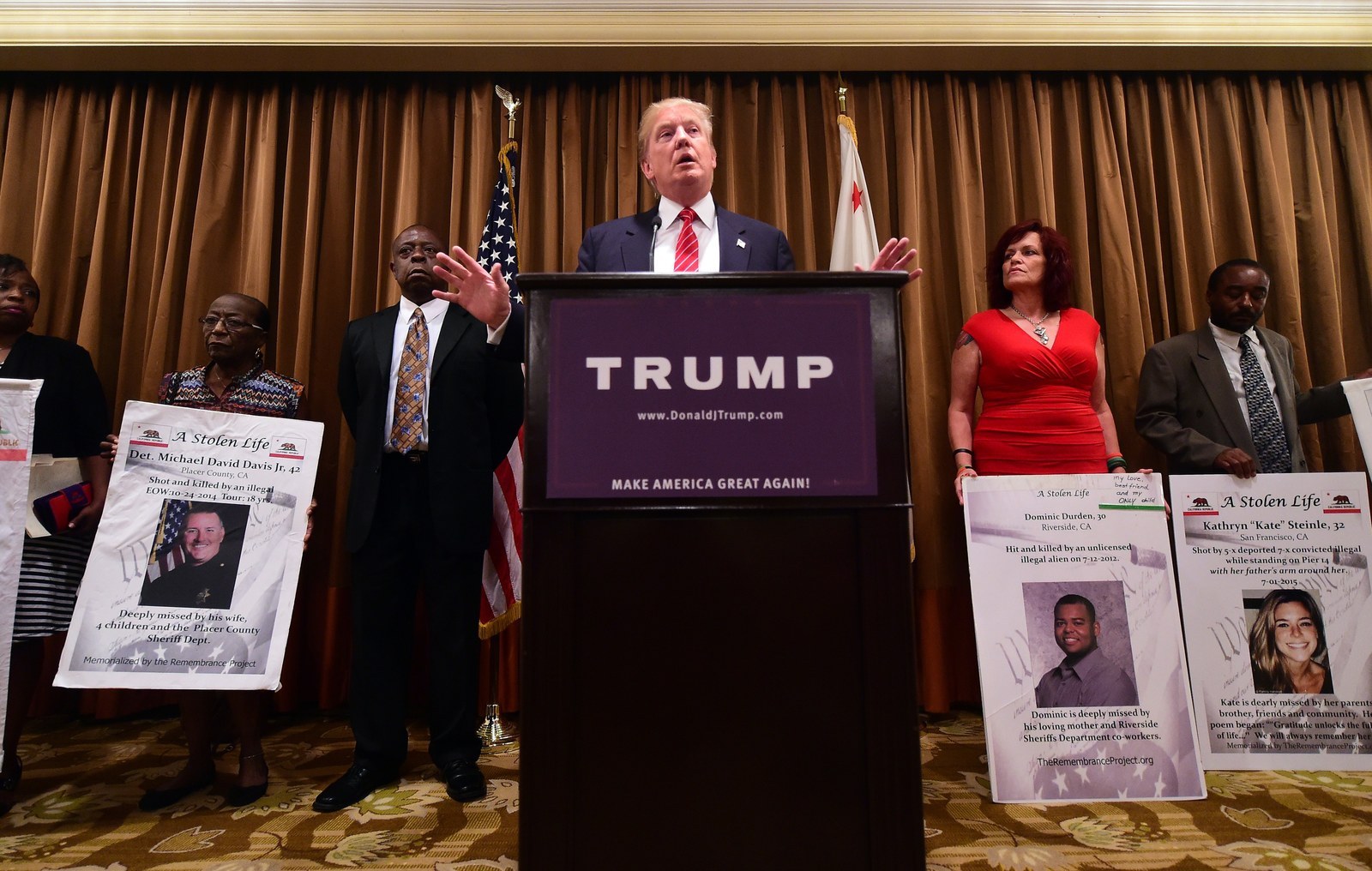

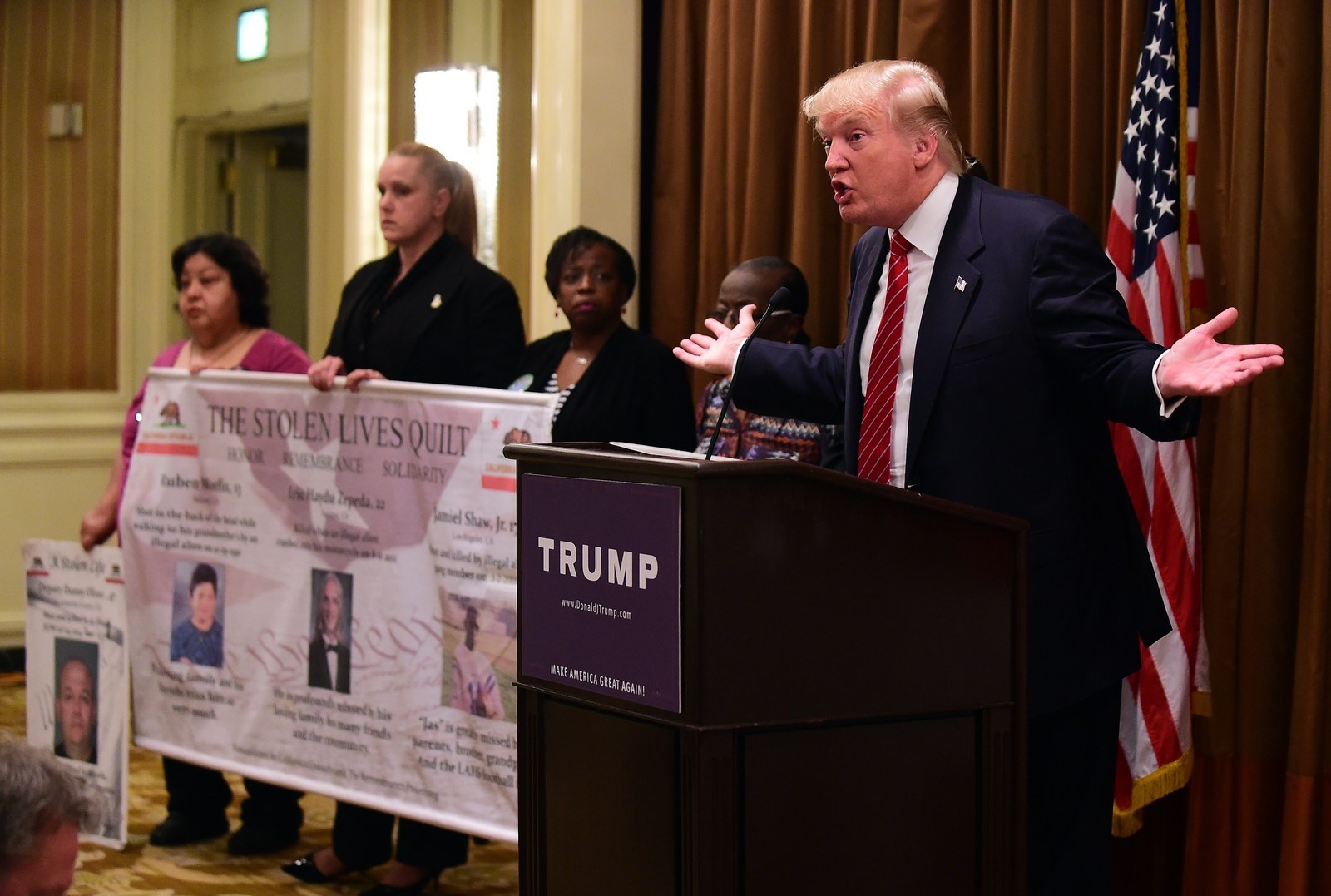

Seeing her cause abruptly in the spotlight, Espinoza mobilized. Wearing a bulletproof vest, she staged a protest on the pier where Steinle was shot. The Remembrance Project began working directly with the Trump campaign: On July 10, the group helped organize a press conference in Beverly Hills, where Trump met with a handful of people whose loved ones had been killed by immigrants. Espinoza said that the Remembrance Project “sent” five of these families to “help educate Mr. Trump.”

“I can’t imagine how everybody in this room doesn’t agree on this subject,” Trump said at the event, speaking to a much larger and more high-profile scrum of reporters than usual for an event involving the Remembrance Project. Behind him, the families held up banners from the Stolen Lives Quilt. “People come in illegally and, in this case, they’ve killed their children! And they wouldn’t have been here. If they weren’t here, their children would be alive. Kate would be alive."

On July 21, the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the subject of immigration and crime. Five family members of people killed by immigrants testified, including Kate Steinle’s father. Mark Krikorian, writing about the hearing for the National Review, noted that “several family members thanked the Remembrance Project, directed by the indefatigable Maria Espinoza, which for years has been the only forum for people like this to tell their stories of Americans killed because of lax immigration policies.”

In the meantime, Trump developed what he calls his “immigration reform” platform, the centerpiece of which is the promise to round up and deport not only the entire population of undocumented immigrants — estimated at more than 11 million — but also their American-born, U.S.-citizen children. In doing so, Trump brought to the center of the American political discussion what had, until then, been a fantasy of the nativist fringe. And, consistent with his inaugural message, Trump justified this position largely on the premise that immigrants cause crime.

Members of the Remembrance Project were thrilled by the way the Trump campaign legitimized the message they had been articulating for years. One of the speakers at the press conference in Washington was Sabine Durden, who had met Trump at the event in Beverly Hills. Durden spoke about her son, Dominic, killed by a drunk driver in 2012. She began her speech by placing an item on the lectern: a black urn, small enough to fit in her palm, embossed with an image of hands clasped in prayer.

“I brought Dominic with me,” she said. “That’s what I have left of my son. His ashes.”

Durden, a naturalized American citizen from Germany, told the story of her son’s death and her subsequent political awakening. Finishing up, she said, “I gotta thank my personal hero, Mr. Donald Trump. When he spoke up against illegal immigration and what it does to our country, he caught a lot of heat, but it opened a door for us. … He accomplished in a few minutes what we tried to do — so many tried to do for years and years.”

“We’re being heard now.”

Fear of the criminal alien has existed for about as long as America has had immigrants. In 1920, speaking before a House committee on immigration, the American eugenicist Harry Laughlin explained that Italians, Russians, and Poles were disproportionately likely to end up in asylums for the criminally insane, describing them as a potential “national menace." Laughlin, whose work would inform the early scientific experiments of the Nazis, was also fond of describing immigration in martial terms: “Immigration is an insidious invasion just as clearly as, and works more certainly in national conquest than, the invading army,” he told Congress in 1924.

Laughlin, who backed up his claims of immigrant criminality with what he called “scientific” data, went on to start the Pioneer Fund, a group dedicated to studying “human nature, heredity, and eugenics.” In the 1980s, Pioneer donated $1.5 million in early financing to John Tanton’s FAIR, the group behind nearly every significant restrictionist organization in the U.S. today. Trump’s campaign announcement struck a chord that FAIR and its affiliated groups had been sounding for years.

Take Steve Salvi, who, under the aegis of the Ohio Jobs and Justice PAC, has maintained a website memorializing people killed by undocumented immigrants since 2006. “Around, I believe, 5,000 Americans are killed every year,” Salvi told me at Espinoza’s event in Washington. “So multiply that by 10 years, you’ve got 50,000 people. Nine-eleven? Three thousand people killed. And we went to war.”

“This deserves more attention,” he continued. “Because it’s preventable. It’s just a matter of enforcing the law.”

When people use statistics to argue that immigrants are more likely to commit crimes than the native-born, the numbers often lead to one of two places. Salvi got his numbers from the office of Rep. King, who frequently says that between 12 and 25 Americans are killed by illegal aliens every day. King says that he “extrapolated” these numbers from a report prepared by the Government Accountability Office in 2011, which concluded that an unspecified number of criminal aliens in federal, state, and local prisons accounted for 25,060 homicide arrests. But that number is often misinterpreted to mean the number of immigrant murderers (rather than the number of offenses), and is itself based on a tiny sample of a larger population that includes arrests dating back to 1955.

“There’s so much bizarre stuff in there,” said Ramiro Martinez, a criminologist at Northeastern University who studies patterns of violent crime in relation to race, ethnicity, and immigration status. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

"I never saw a Mexican flag anywhere — not in our home, you know? Itwas just America and the Bible."

The other oft-cited source is the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which has data showing that a large percentage of federal prisoners are noncitizens, whether with or without legal status. But federal prisons house a small fraction of the incarcerated population, as well as the entirety of people imprisoned for immigration offenses, which are exclusively federal. That means federal prisoners cannot be considered representative of the criminal population at large.

Supporting the exact opposite conclusion — that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than the native-born population, in some cases by large margins — there are dozens of studies conducted over a hundred years. They vary widely in their methodologies and sources of data, from analyses of census figures on institutionalized populations, to local assessments of neighborhoods and cities, to psychiatric and longitudinal studies of immigrant youths.

Nevertheless, the government does not directly count the number of crimes committed specifically by immigrants, be they legal or illegal; on some level, every analysis involves extrapolation. It is impossible to know whether the murder rate is rising or falling among immigrants in any given year in the same way one could answer the same question about, say, white people or young people. And yet, as Martinez, the criminologist at Northeastern, writes, “the major finding of a century of research on immigration and crime is that immigrants display tremendous variations over time and space in their criminal involvement and, contrary to popular opinion, nearly always exhibit lower crime rates than native groups.”

Lack of data leads the Center for Immigration Studies, the most prominent think tank focused on supporting immigration restrictions, to argue that solid empirical conclusions on immigration and crime are impossible in either direction. CIS and others with comparatively moderate restrictionist views often contend that the larger question, in any case, is irrelevant, because any number of murders by undocumented immigrants is unacceptable and a sign of ineffective immigration policies. Either way, the absence of direct data leaves an immediate void that can be filled with disquieting anecdotes about murderous immigrants.

That is why Espinoza’s aggressive focus on personal grief is so useful to the nativist cause, says Terri Johnson, the executive director of Center for New Community, a group that tracks what it calls “organized bigotry.” It is true that undocumented people commit crimes, sometimes horrible ones, and that these crimes leave people reeling and aggrieved. “That makes it harder to critique the hate strain in it, because there is real pain there,” Johnson said. “But some of that is a little foggy. Where does the real pain end, and where is it getting manipulated?”

The Remembrance Project’s speakers range from the well-rehearsed to the rough-edged. In Washington, Dan Golvach was among the latter. In January, his son Spencer was shot in the head by a man named Victor Rodriguez Reyes, who was on a spree in Houston: He shot into Spencer’s car at a stoplight, shot and killed a 28-year-old named Juan Garcia the same way, and was killed by police. Golvach says he later learned from a police investigator that Rodriguez had been deported four times.

Golvach has stubble and longish, straight hair parted down the middle. He’s a professional musician who plays four nights a week and runs a recording studio. Spencer, his son, played bass in a prog rock trio with his younger brother on drums; they had started to gain recognition in Houston by the time Spencer died, at 25. “They always joked that I breeded a rhythm section,” Golvach said. “We’re all three massive Led Zeppelin fans.”

"Where does the real pain end, and where is it getting manipulated?"

After Spencer’s death, Golvach got a few calls from politicians, and one from Maria Espinoza. “The only one that I felt was sincere was Maria,” he said. “Because, you know, Maria and Tim could be going fishing if they wanted ... but instead she does this.”

Espinoza regards her cause as apolitical, arguing that she calls not for changes to the existing laws but merely for their enforcement. Of the cliché that the immigration system is broken, she says: “I have my vacuum cleaner at home, and if I don’t plug it in or turn it on, it won’t work. That doesn’t mean it’s broken.”

This resonated with Golvach, who sees the political implications of his son’s death not as a matter of “ideological debate” but as common sense: “You don’t leave your door open all night. And if someone comes into your house, you don’t ignore it.” Golvach takes pride in not identifying as a Republican, not only because the party is beholden to corporate interests that benefit from undocumented labor, but also because he doesn’t care “what grown-ups do with themselves.” “I’m just a pissed-off dad,” he said. “It wasn’t a gay person that came in and shot my kid.”

It was Golvach who had the biggest applause lines earlier in the day. He and Spencer’s mother, he explained, consider their son’s killer nothing more than a “foot soldier.” He has a problem with the way people “frame this as a debate on immigration. I refuse to call this immigration. An immigrant is one who comes into your country on your terms and obeys your laws. Someone that comes into your country on their terms and disregards your laws is an invader.”

And who is left to react to this invasion, if the media and the corrupt political class won’t acknowledge it? “To honor the memory of all these young Americans, all good people, and to protect other Americans,” Golvach said, “we have to fight this war.”