It will be two years minimum before the U.S. government considers M's application for asylum. He'll have to wait, because like tens of thousands of others, he has no place else to go.

Before he sought refuge, M. was in the U.S. legally as a sophomore at a public college in upstate New York. That ended when he was outed as gay to his parents in Vietnam, after confiding in a cousin whose loyalty he miscalculated. His parents immediately cut him off financially in an effort to force him back home so they can send him to a camp that will "cure" him of his sexual orientation.

"I'm stranded," M. says, standing on a Bronx sidewalk dwarfed by the public housing complex that, courtesy of a friend generous enough to share her twin bed, he is calling home for now. "I can't really do anything until they decide my case." (M. asked that BuzzFeed News withhold his name for fear that speaking publicly would jeopardize his asylum claim.)

Other than going underground as an undocumented immigrant, the U.S. asylum system is M.'s only recourse to avoid returning to a life of physical and emotional abuse in Vietnam. But that system, according to federal data and to the accounts of asylum seekers and their lawyers, is crippled by backlogs. Around the country, asylum seekers are waiting anywhere from two to four years just to schedule an initial interview with immigration officers, merely the first step in a long adjudication process.

This far exceeds the government's own standards, which state that asylum seekers should be interviewed within 45 days and have their cases decided within roughly six months. By and large, the government hewed to this standard before the current backlog, according to more than a dozen asylum attorneys interviewed by BuzzFeed News.

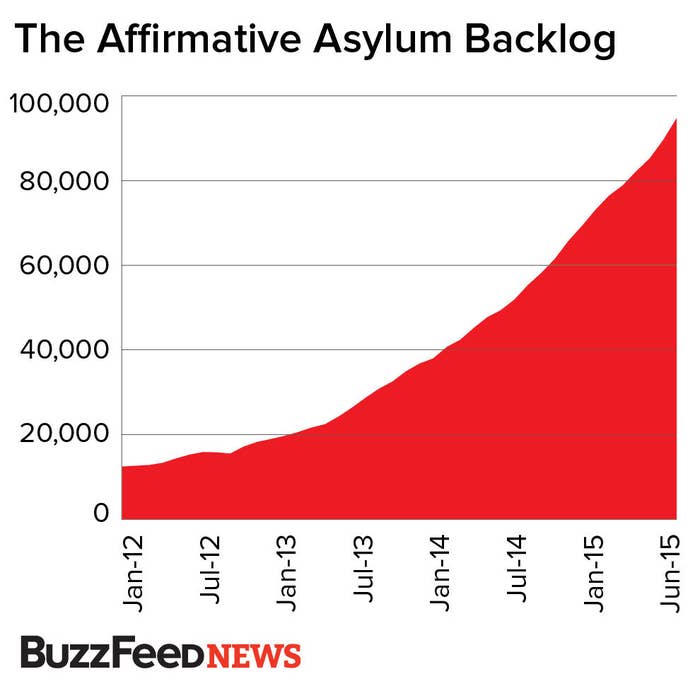

The number of applicants waiting in the backlog has grown more than sixfold, from roughly 12,500 in January of 2012 to nearly 95,000 in June of this year. Meanwhile, the number of cases adjudicated in a given month by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the federal agency that processes immigration applications, has only grown by 40 percent, from roughly 2,400 to 3,700. These asylum seekers cannot work legally for the first five months their application is pending, during which time many struggle to support themselves financially. Until their case is decided, they are barred from receiving any federal benefits. For many, this means being shut off from access to desperately needed medical care. Others have families stranded and in danger in the countries they fled. Once they obtain asylee status they can bring their families legally to the U.S., but, in the meantime, they have no choice but to wait.

The system became overloaded following a sudden rise in the number of Central Americans fleeing gang violence by crossing into the U.S. from Mexico in 2012. The surge peaked with last year's unaccompanied child migrant crisis, in response to which the government jailed thousands of Central American families and sped up their deportations. Meanwhile, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services dedicated a growing share of resources to interviewing migrants at the border. These resources were siphoned, according to a report by the agency's ombudsman, from the cases of affirmative asylum applicants — those who apply proactively from the interior of the country, rather than as a defense against deportation.

"I've been practicing asylum law for 20 years," said Paul O'Dwyer, a lawyer in New York who is suing the federal government in a class action on behalf of asylum seekers stuck in the backlog. "My opinion, and the opinion of most private attorneys who practice asylum law, is that the asylum adjudication system simply no longer works."

A USCIS spokesperson told BuzzFeed News that the agency has doubled the number of asylum officers in the last two years, although it's not possible to specify how much of this manpower is assigned to border cases stemming from the surge. In spite of this increase, funding levels for the asylum division have remained at a steady 2% of USCIS's total budget, according to data provided by the agency.

Hence the continuing limbo of cases like M.'s. — cases that fit broadly into the government's standards for asylum and which in prior years would have had a good chance at a quick resolution.

M. is his father's first and only son, as his father was to his grandfather. He bears tremendous pressure to carry the patrilineal bloodline, and his family views his sexual orientation as a cataclysm. When M. was a child, he liked to wear makeup and his sisters' dresses. He continued to do so until his father's beatings became severe enough to suppress the urge.

But the pressure on M. had one benefit: His family, which had climbed its way to the middle class on the back of a small appliance store, expected him to surpass their success. So when M. turned 16, they sent him to America to finish high school and start college. M. jumped at the chance, even though the school his parents chose was a Christian academy deep in Kentucky. After a revelatory class visit to New York City, he convinced his parents to send him to college upstate — just far enough from the city to seem sufficiently sheltered.

"I was privileged before this, I guess," M. says. "I was an international student. My parents were paying my tuition. Now I don't really have anything. But waking up and not thinking about what I'm going to do today to not be perceived as gay… that's profoundly valuable to me."

M. sometimes dwells on the fact that many cases are more, as he puts it, "extreme" than his. Among the asylum seekers who spoke to BuzzFeed News, there is the Syrian dentist who was driven from her lab by Islamist gunmen and whose son remains in Damascus. There is the Colombian activist whose husband was killed in broad daylight by narco-paramilitaries and whose daughter remains in Medellín. There is the gay man from Cameroon, where homosexuality is illegal, who contracted HIV during a gang rape that he wouldn't dream of reporting to the police.

Only a few years ago, these kinds of cases would probably have been dispatched quickly and relatively painlessly, said Camille Mackler of the New York Immigrant Coalition, who practiced asylum law privately for several years. "If this backlog hadn't happened, and if the system functioned as it should, [immigrants with strong cases] would have gotten asylum within three to four months and gone on with their lives," Mackler said.

The same is true of M.: There are clear pathways in the law for LGBT students who lose their visas and livelihoods after coming out to their families. But now M. is down to his last $300, with a couple of months to go before he can get a work permit. "I'm just trying not to spend anything," he says, meaning he mostly whiles away his days reading. The idleness is getting to him. "When you're just home all the time, not being productive — it's depressing," he says, riding a northbound bus in the Bronx to meet Dee, the friend whose twin bed, food stamps, and MetroCard he's sharing.

M. has the benefit of making friends easily. Well before he felt comfortable with the idea, Dee insisted that he stay with her and her sister, two brothers, and their parents in their cramped apartment in the Bronx. Dee's family came to New York from Jamaica when she was a child, and it took them several years to resolve their immigration status.

"We can relate," she says, standing with M. in line for a burrito outside Fordham Plaza. "Now my parents call us married. They're like, 'feed your husband!'"

She asks how long, exactly, it will take for M.'s case to be resolved. The government, as it turns out, recently posted new timetables online. "In New York," M. says, "they're hearing cases from 2013. It could be worse. In Los Angeles they're hearing cases from 2011."

Dee nods. "So, 2017? You'll be good?"

M. smiles, shrugs, and doesn't answer.