Sidney Poitier, the trailblazing Bahamian American actor whose commanding talent and immense charm helped him shatter racial barriers in Hollywood and pave the way for generations of Black talent, died Thursday. He was 94.

His death was announced by Bahamas Prime Minister Philip Davis, who said in an address that his country was mourning the cultural icon.

“We admire the man, not just because of his colossal achievements,” Davis said, “but also because of who he was, his strength of character, his willingness to stand up and be counted, and the way he plotted and navigated his life’s journey.”

The first Black man to win an Oscar, Poitier was revered around the world for helping to advance US racial dialogue in the turbulent 1960s through his art and celebrity.

At their core, his most celebrated performances — a wandering and wry ex-soldier helping a group of nuns build a chapel in Lilies of the Field; the patient yet stern teacher to an unruly London high school class in To Sir, With Love; a cerebral detective battling racism and crime in the Deep South in In the Heat of the Night — were each built off a quiet elegance and beguiling grace that were unmistakably Poitier’s own.

A lion of American cinema, Poitier has been championed as a pioneer and personal role model by some of the country’s most celebrated Black entertainers, including Denzel Washington, James Earl Jones, and Oprah Winfrey. At a 1992 event honoring Poitier, the actor was stunned to discover civil rights icon Rosa Parks was in the audience. She, too, admitted to being a Poitier fan.

“It’s been said that Sidney Poitier does not make movies, he makes milestones —milestones of artistic excellence, milestones of America’s progress,” said former president Barack Obama in honoring the actor with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009 — some 42 years after Poitier’s character in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner dreamed of his biracial children one day growing up to be president.

Poitier was born two months prematurely in Miami in 1927, and his parents were impoverished tomato farmers visiting from the Bahamas. At a loss, his mother took her weak baby to a fortune-teller who assured her: “Don’t worry about your son. He will not be a sickly child. He will walk with kings. He will step on pillars of gold. And he will carry your name to many places.” (Evelyn Poitier lived long enough to see her son become the first Black Best Actor winner.)

Raised in the Caribbean nation until he was a teenager, on an island he once said had just two white people on it, Poitier grew up unaware of the racial politics simmering just across the sea in the US. “No one ever told me, ‘You must be careful because there are things out there that are not friendly [for Black people],’” he later said.

After arriving in the US, and a brief service in the medical corps during World War II, he was rejected from New York City’s American Negro Theater because of his accent. Fueled by the sting of rejection, he fastidiously listened to radio announcers, mimicking their enunciation to shed his own until he was accepted into the same theater group just six months later.

A career on Broadway followed, but cinema proved more difficult due to the scarcity of roles for Black actors that weren’t steeped in racial stereotypes. “It was difficult. [Black actors] were so new in Hollywood. There was almost no frame of reference for us except as stereotypical, one-dimensional characters,” he told Winfrey in 2000. “Not only was I not going to do that, but I had in mind what was expected of me — not just what other Blacks expected but what my mother and father expected. And what I expected of myself.”

His early screen roles reflected his unwillingness to cater to Hollywood’s restrictive demands in favor of more challenging fare: a Black doctor caring for a bigoted white criminal in 1950’s No Way Out (so controversial it was banned in the British-ruled Bahamas and parts of the US); a clergyperson in apartheid South Africa in Cry, the Beloved Country (1951); and an inner-city high school tough brimming with untapped potential in Blackboard Jungle (1955).

In 1959, he became the first Black man to be nominated for a competitive Academy Award for his role as a prison escapee in The Defiant Ones — a film he later said he was only able to do because he agreed to act in another film he found more problematic, 1960’s Porgy and Bess.

He also starred in the 1959 milestone premiere of Lorraine Hansberry’s now-classic play A Raisin in the Sun, the first play ever written by a Black woman to show on Broadway. “Never before,” declared the writer James Baldwin, “had so much of the truth of Black people’s lives been seen onstage.”

But it was during the 1960s that Poitier truly came into his own, delivering a series of performances that would leave indelible marks on American cinema.

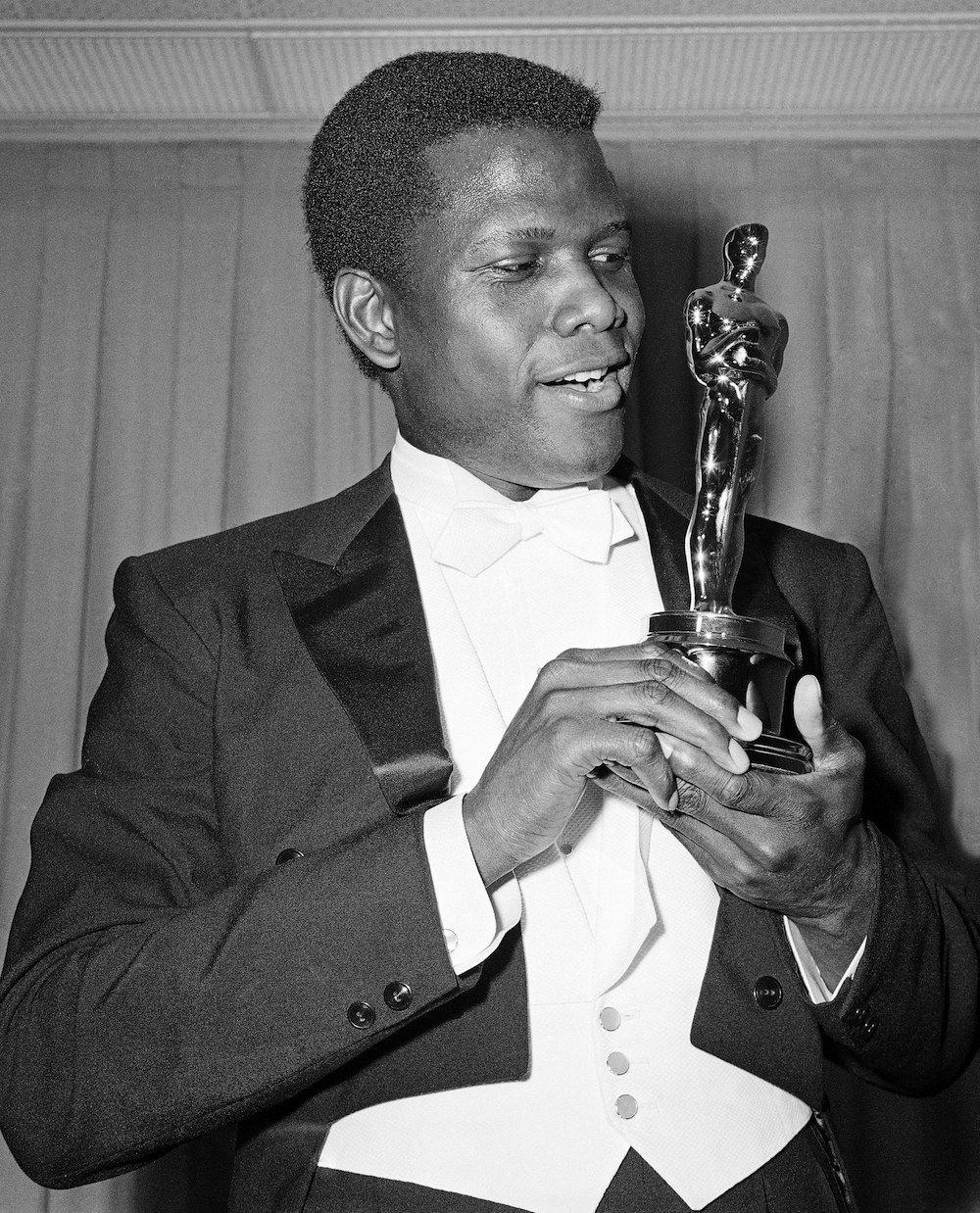

He won the Academy Award for Best Actor for 1963’s Lilies of the Field, cementing his place in movie history as the first Black man to take home an Oscar. (Hattie McDaniel had won the Best Supporting Actress prize in 1940 for her role in Gone With the Wind.)

Not expecting to prevail in a category that included Albert Finney, Richard Harris, Rex Harrison, and Paul Newman, Poitier had prepared no acceptance speech but took the stage to thunderous applause.

“Because it is a long journey to this moment, I am naturally indebted to countless numbers of people,” a visibly emotional Poitier told the Oscars crowd in his acceptance speech.

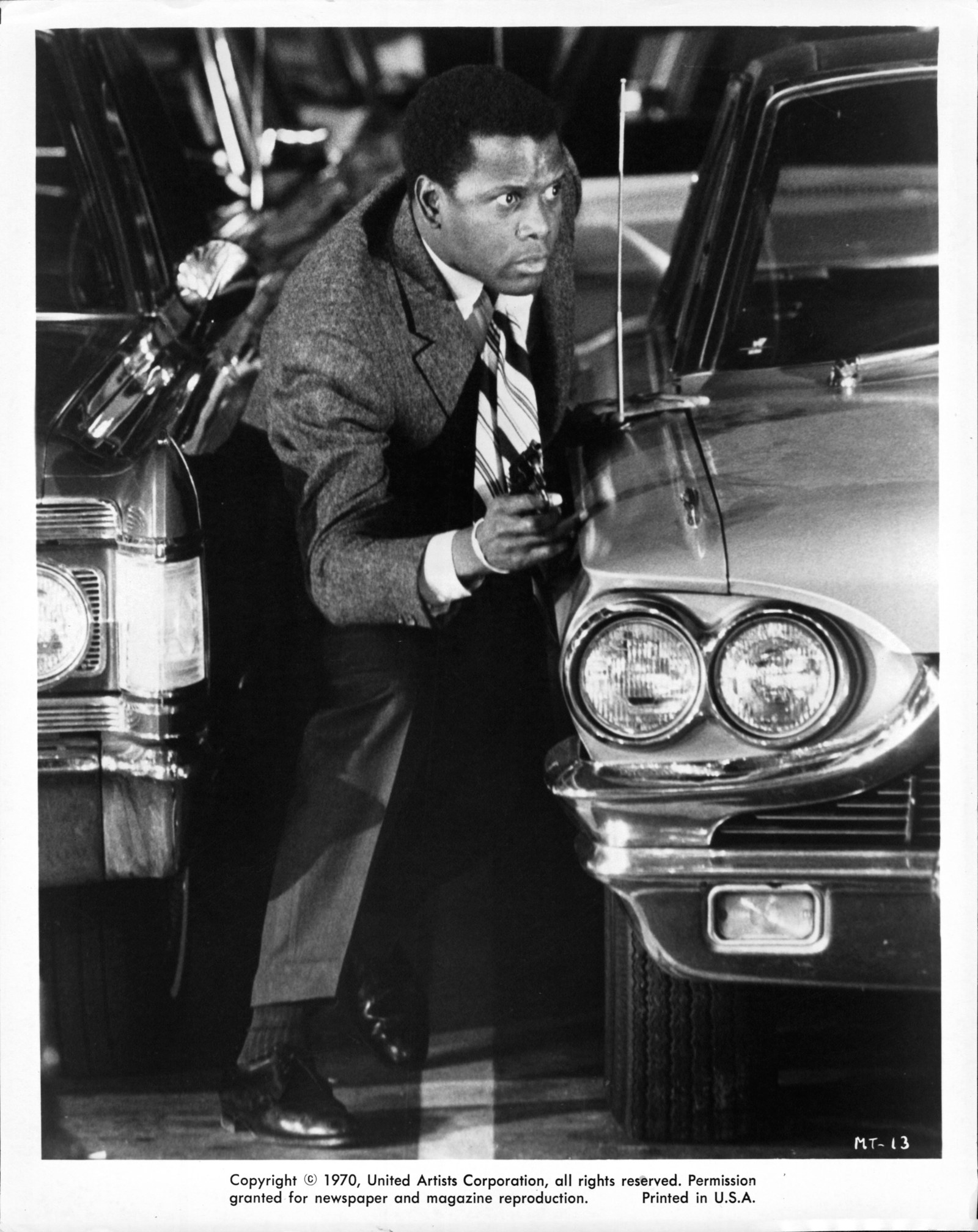

His most prolific year came in 1967 with the release of To Sir, With Love; In the Heat of the Night; and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, one of the most notable films to so directly address and debate the racial politics that America was grappling with during the decade. As Poitier’s character meets the supposedly enlightened parents (Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, in his final role) of his white fiancé (Katharine Houghton), the four must confront the prejudices and fears of the era in 100 minutes of domestic discussion.

“You and your whole lousy generation believes the way it was for you is the way it’s got to be. And not until your whole generation has lain down and died will the dead weight of you be off our backs!” Poitier’s character tells his father (Roy E. Glenn) in one of the film’s most memorable speeches. “You think of yourself as a colored man. I think of myself as a man.”

By 1967’s end, the most famous Black man in cinema was also the industry’s top-grossing box office star of the year.

Poitier’s most iconic characters were, by and large, honorable men — endlessly patient, reliably affable, and wholly stripped of any semblance of sexuality — a conscious choice, he said, because of the pressures of history weighing upon him.

Citing Quincy Jones, Winfrey later told Poitier he had “created and defined the African American in film.”

“It’s been an enormous responsibility,” he acknowledged. “And I accepted it, and I lived in a way that showed how I respected that responsibility. I had to. In order for others to come behind me, there were certain things I had to do.”

His character choices also earned him his detractors, though, with some turning on him for supposedly playing exclusively to white America. “He thinks these films have really been helping to change the stereotypes that Black actors are subjected to,” African American playwright Clifford Mason wrote in a famous 1967 New York Times piece titled “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?” “In essence, they are merely contrivances, completely lacking in any real artistic merit. In all of these films he has been a showcase nigger, who is given a clean suit and a complete purity of motivation so that, like a mistreated puppy, he has all the sympathy on his side.”

Poitier told Winfrey the “Uncle Tom” backlash was hurtful but not totally unexpected in the turbulence of the civil rights era: “It was far from the truth, but I understood the times. There was a public display of all the rage that [Black people] had built up over centuries.”

“What the name-callers missed was that the films I did were designed not just for Blacks but for the mainstream,” he said. “I was in concert with maybe a half dozen filmmakers, and they were all white. And they chose to make films that would make a statement to a mainstream audience about the awful nature of racism.”

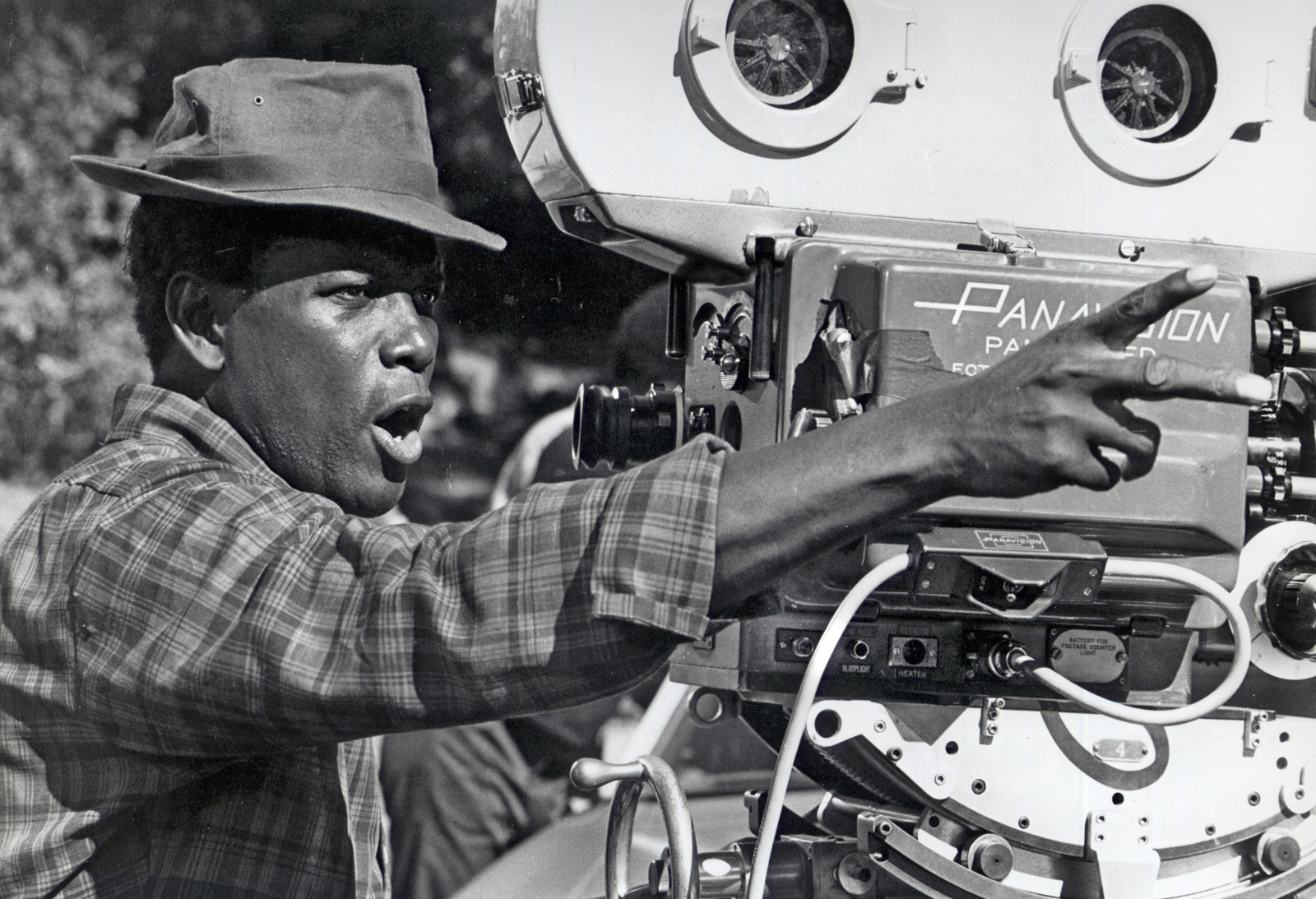

The criticism led Poitier to a “crossroads” in his career, as he termed it, moving him behind the camera to the director’s chair.

Apart from reprising his In the Heat of the Night role in two sequels, his career in the 1970s was most notable for the many films he directed (and in which he also occasionally starred): the 1974 comedy Uptown Saturday Night, starring Billy Cosby and Harry Belafonte; two more Cosby films, Let’s Do It Again (1975) and A Piece of the Action (1977); and 1980’s Stir Crazy, featuring Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. (He also helmed the 1990 vehicle Ghost Dad, one of the most terrific flops in movie history.)

As the decades continued, Poitier delivered largely forgettable roles on television and in cinema, but his iconic status had already been cemented in the American cultural canon.

It took almost 40 years for a second Black actor to win the Best Actor prize, with Denzel Washington claiming the statue in 2002 for Training Day.

Poitier was in the audience that night, too, having been bestowed an Honorary Oscar for his work in the industry inscribed with the words, “To Sidney Poitier, in recognition of his remarkable accomplishments as an artist and as a human being.”

As Washington took the stage, Poitier looked on, beaming.

“Forty years I’ve been chasing Sidney, they finally give it to me. What do they do? They give it to him the same night,” Washington joked. “I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney. I’ll always be following in your footsteps.”