The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Incoming.

When the coronavirus began making headlines across the US in February and March, Alix Oreck started planning. A physician for hospitalized patients in Parsons, Kansas, she and her team shut down elective surgeries and started devising field hospitals in case infections soared beyond control. But a surge in the town of about 9,600 residents — or in the whole state of Kansas — never arrived.

Now, though, things are very different. Hospital beds in Parsons have been filling up over the last two months, her hospital has expanded into previously unused wings, backup physicians are being called in, and some of her colleagues have contracted the virus, which has been particularly distressing to watch. But as Oreck and her fellow medical workers confront a long, dark winter, her county still refuses to enforce a mask mandate.

“I’m just incredibly nervous,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I know it’s going to get worse, and we’re already overworked and overtaxed and out of equipment and out of rooms. It’s going to get uglier and uglier.”

Oreck said it can sometimes feel like no one — not the government, not the media — is paying attention as she and her colleagues drown.

“Not that I blame them,” she said. “Who gives a shit about Parsons, Kansas, when every town in America is going to have this struggle?”

In the early months of the pandemic, cities like New York were hit hardest as the virus spread more quickly in high-density areas. But the second and third waves have swept across the country into more rural states, infecting smaller cities and remote communities, many of which never took restrictive measures to prevent the spread of the virus after being spared from the first wave. An analysis by NPR in September found that people from outside large metro areas accounted for one-fifth of the first 100,000 Americans to die of COVID-19. In the second 100,000 deaths, they accounted for almost half. The share of deaths almost tripled in smaller towns and rural regions.

That has only increased as colder weather has prompted more people to gather inside, where the virus spreads more easily via tiny water droplets called aerosols that can linger in the air. With the US recording more than 200,000 new infections on Wednesday, CDC Director Robert Redfield warned that January and February would likely be “the most difficult time in the public health history of this nation.” More than 1 million rural Americans are now among those who have tested positive, with infections spreading out of control in 7 out of 10 rural counties, according to the National Rural Health Association (NRHA).

“From a public health perspective,” said NRHA CEO Alan Morgan, “COVID in rural America is a horror story.”

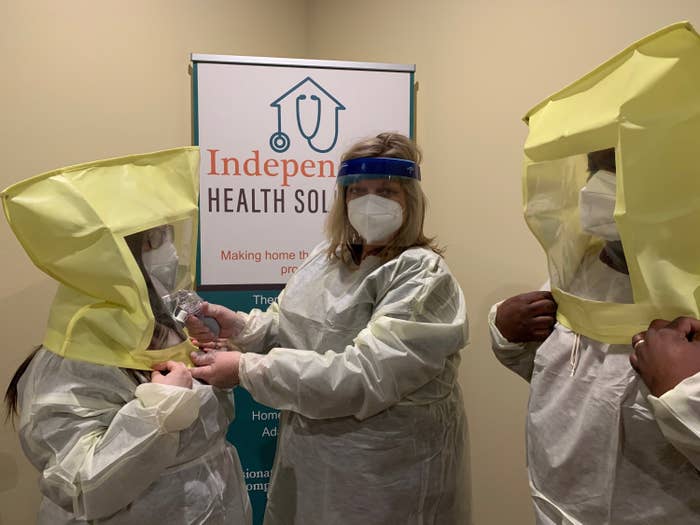

Healthcare workers in smaller towns are as exhausted and despondent as their counterparts in bigger cities. They, too, are facing shortages of personal protective equipment and are watching hospital beds and ICU wards fill up rapidly. But these medical workers also often find themselves treating patients that they know.

“In a rural environment, health care really is personal,” said Nick Wendell, a city council member in Brookings, South Dakota, whose cousin works at a hospital in the town of Gregory, population 1,200. “There’s an intimacy to the patient you’re treating. You know them well. They may be members of your church or former high school class or your friend’s parents. There’s a very up-close aspect in a small town.”

Losing a patient can thus be a uniquely devastating experience for rural healthcare workers.

“It’s a really hard one because we love and care for them in a different way,” said Ashley Kingdon-Reese, a home health nurse in Huron, South Dakota, population 13,600. “We know their whole family, the name of their pets, their kids. We’re part of their lives, so when it begins to get them, it’s hard and it’s not quick.”

A nurse practitioner in Jonesboro, Arkansas — who asked not to be named so that her hospital, which serves as a hub for several rural communities, was not identifiable — recalled treating a patient who is still severely ill with COVID-19 and whom she has known for years. When the patient’s X-rays came back, the nurse could tell they resembled others she had seen from patients who had suffered extensive lung damage and were facing likely death. “I don’t like to see what’s coming for people that I know,” she said.

“‘It’s not fair. I don’t want to die,’” she said the patient told her. “That’s a hard thing to hear from someone that you know.”

“From a public health perspective, COVID in rural America is a horror story.”

Roughly 46 million Americans live in rural areas, and due to systemic health inequities, many face an increased risk of becoming very sick with COVID-19. According to the CDC, rural Americans are more likely to smoke, have high blood pressure, be obese, and be uninsured. Areas with Native American populations face even worse problems.

Health systems in these areas have also been strained in recent years. Even a small outbreak can test the limits of hospital capacity. More than 128 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, according to Senate Democrats, meaning patients requiring serious care often have to be transported far distances, and sometimes across state lines, to find a hospital bed.

This presents a different dynamic for rural healthcare workers who may be treating patients who have arrived from far away. Oreck, the Kansas hospitalist, said her ICU recently accepted a transfer of man from some 400 miles away near the Colorado border. She had held his hand and told him he’d get better under their care, but he died very quickly.

“When it’s someone in the community, I can express my condolences and grieve with people,” she said, “but taking in someone from far away and taking care of them and then not having any frame of reference in which to grieve for them or their family is hard.”

Perhaps no states have been as hard-hit in recent months as the Dakotas. In November, North Dakota had the highest daily mortality rate of anywhere in the world. One in every 800 North Dakotans has died from the virus. The situation isn’t much better in South Dakota, where 1 in every 1,000 residents has died.

“I think every region of South Dakota is being impacted,” said Wendell, the city council member in Brookings. “We’ve got a lot of rural, very sparsely populated parts so in the case of an infectious disease like COVID, it’s taking longer to get to every corner of South Dakota, but it’s in every corner now.”

Residents in these areas are more likely to be conservative and highly resistant to mask mandates or social distancing requirements. It took until mid-November for North Dakota’s Republican governor, Doug Burgum, to reverse course and order the public to wear masks. And South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, a vocal supporter of President Donald Trump, continues to falsely say there is no evidence mask-wearing slows the spread of the virus.

“There are people still in denial that this is real,” said Kingdon-Reese, the South Dakota nurse who serves as government relations chair for her state’s nurses association. “Everything from QAnon to Trump supporters has made this so political. It’s almost more damaging than the disease itself.”

“It feels like we’re fighting two pandemics: the virus and misinformation,” Kingdon-Reese said.

“It feels like we’re fighting two pandemics: the virus and misinformation."

Researchers at the University of Kansas recently found a 50% reduction in the spread of COVID-19 in counties that had enforced a mask mandate compared to those that hadn’t, even when controlling for other social distancing measures that were put in place. When the study was discussed on Fox & Friends on Tuesday morning, the conservative hosts seemed almost surprised by the findings. “It means — apparently — masks work,” anchor Steve Doocy said.

Fox News and other conservative media outlets have repeatedly spread confusion or doubts about the severity of the pandemic to their audiences with real-world consequences. When Wendell and his colleagues on the Brookings City Council issued a mask mandate in September, he said a town hall crowd booed and made animal noises at them and their advising epidemiologists. “In a community like ours, the very same doctors we trust with our children and our parents are telling us this is severe and the simple act of wearing a mask could slow the spread, and we’re choosing not to trust them,” he said. “It tells me something’s broken.”

Of course, the lack of trust in scientists or the government extends well beyond South Dakota. During the election, as the US experienced a soaring third coronavirus wave, Trump attempted to defer any blame by spreading misinformation and falsely claiming the media would stop discussing the pandemic after Election Day. The Jonesboro, Arkansas, nurse practitioner recalled giving a patient stitches for a cut who parroted the president, telling her, “You won’t hear any more about this virus once the election is over.”

“I said, ‘You’re wrong. People you know are still going to die from it,’” she said.

In Kansas, Oreck said she is tired of feeling like the “other” when she is the only one wearing a mask in her supermarket. One close friend whose wife died from complications of the virus in August still refuses to wear one.

“I’ve talked to him about it ad nauseam. For years, he’s come to me for medical advice and he’s asked me to speak at his church, and yet he will not listen to me,” she said. “It makes me want to cry. It’s incredibly frustrating.”

He’s not the only close friend or family member who Oreck said she has struggled to convince “even though I am the medical professional they have come to when they needed stitches on a Sunday night, or when their kid has a rash, or someone gets a cancer diagnosis and they want to hear what I think.”

“Now, or at least in this arena, my professional opinion doesn’t seem to count for much.” ●