Helmut Kohl, whose lengthy tenure as German chancellor saw him reshape modern Europe by leading the reunification of his country as the Cold War ended and laying the framework for the European Union, died Friday at age 87.

His death was confirmed by his former political party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). "We are sad," the party said in a tweet. "#RIP #HelmutKohl." Steffen Seibert, a spokesman for the government, also confirmed the death.

According to the Bild newspaper, which was first to report the news, Kohl died at his house in Ludwigshafen, south of Frankfurt. No other details were immediately available.

In June 2015, Kohl had been in intensive care in critical condition, according to Der Spiegel, after an operation on his intestine. After suffering a stroke in 2008, he had become increasingly frail and was confined to a wheelchair.

The center-right statesman led democratic West Germany from 1982–1990 during the final years of the Cold War, before serving as chancellor of a reunited Germany from 1990-1998 — the longest term in office for any democratically elected German leader.

Through negotiations with former French President François Mitterrand, Kohl also was instrumental in drafting the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which created the European Union and led to a single currency, the euro.

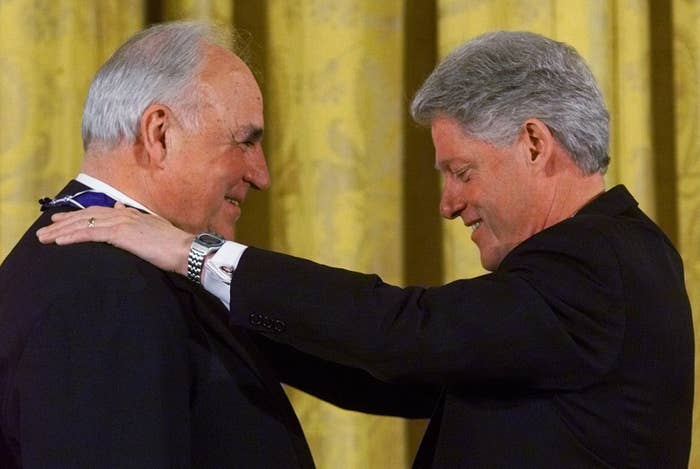

"Future historians will say Europe's 21st century began on his watch," US President Bill Clinton said in 1999 when awarding Kohl the Presidential Medal of Freedom. "The story of Helmut Kohl is the story of 20th-century Germany."

In a statement after his death, President George HW Bush said he and wife Barbara were mourning the loss of "a true friend of freedom, and the man I consider one of the greatest leaders in post-War Europe."

"Working closely with my very good friend to help achieve a peaceful end to the Cold War and the unification of Germany within NATO will remain one of the great joys of my life," Bush said. "Throughout our endeavors, Helmut was a rock — both steady and strong. We mourn his loss today, even as we know his remarkable life will inspire future generations of leaders to dare and achieve greatly."

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg also paid tribute, calling Kohl "the embodiment of a united Germany in a united Europe."

"When the Berlin Wall fell, he rose to the occasion. A true European," Stoltenberg tweeted.

Born April 3, 1930, in the Rhine river city of Ludwigshafen in the southwestern state of Rhineland-Palatinate, Kohl's nationalistic father and elder brother fought for Nazi Germany in World War Two, with his brother dying in the conflict. In 1945, Kohl himself was drafted to serve in the war's frantic, final weeks, but fighting ended before he could take up arms.

In 1947, at the age of 16, he became member number 246 of the new CDU, a political party that has since prospered in Germany and is now led by current Chancellor Angela Merkel. At 19, he was briefly detained at West Germany's border with France for trying to remove barriers between the countries in a bid to promote peace.

Fresh after graduating with a doctorate in political science from the University of Heidelberg, Kohl was elected to the state legislature in 1959, rising to the top post of minister president a decade later. He was also elected the national CDU chairman in 1973.

As the CDU's candidate for chancellor in the 1976 federal elections, Kohl lost out to Helmut Schmidt of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), who was able to form a coalition government with the Free Democratic Party (FDP) that continued until the FDP switched its alliance to the CDU in 1982. With Kohl installed as chancellor, the coalition won a hefty majority in the Bundestag, or German Parliament, in 1983 elections.

Kohl's early years as leader were marked by heartfelt efforts to reach out to Germany's former wartime foes. In an emotional visit to Verdun in 1984, where French and German troops had fought a bloody battle against one another in World War One, Kohl and Mitterrand silently held hands for minutes before a memorial in an iconic moment of postwar reconciliation.

In 1984, Kohl became the first postwar German leader to speak before the Israeli Knesset. "I come as the first chancellor of the postwar generation, as the representative of a new Germany, which regards respect for human dignity, justice, peace, and freedom as the highest precepts," Kohl told his hosts upon arrival. However, his visit saw Holocaust survivors try to tear down West German flags or throw stones at his motorcade, according to a New York Times report at the time. The trip also came after he had agreed to sell arms to Saudi Arabia as part of a security agreement that had caused anger in Israel.

In 1985, for the 40th anniversary marking the end of World War Two, Kohl convinced US President Ronald Reagan to accompany him on a controversial visit to a war cemetery for Germany's dead in Bitburg, in addition to visiting the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. ''We who were enemies are now friends,'' Reagan said in a speech after the visit, which angered some in the United States. ''We who were bitter adversaries are now the strongest of allies. In the place of fear we have sown trust, and out of the ruins of war has blossomed an enduring peace.''

After Kohl was re-elected in 1987, there were signs that Europe was on the verge of major upheaval, with Erich Honecker that year becoming the first East German leader to visit his Western neighbor. With the eventual fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of communism in East Germany in 1989, Kohl was adamant Germany needed to be reunified as quickly as possible.

He quickly sought to lobby both Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and his NATO allies to give their blessings, or at least reluctant acceptance, to a unified Germany. He also helped campaign for CDU-aligned parties in the East during their first democratic elections in 1990, resulting in a government there that was also committed to reunification.

After signing a treaty in May 1990 to merge the two countries' economic and social welfare systems, Kohl proceeded over the objections of his own economists to allow for an equal exchange of the worthless East Germany currency. The absorption of the crippled Eastern economy ultimately proved immensely strenuous, eventually leading to tax increases and cuts to spending after the two countries were officially reunited on Oct. 3, 1990.

After his coalition was resoundingly elected to lead the new Germany in elections held just months after reunification, Chancellor Kohl focused his efforts on helping to finalize the integration of Europe. Fears persisted, especially in Germany, on what the country might look like as it gained in economic might, given its actions earlier in the century. Kohl, however, insisted that Germany's participation in a multination European group would constrain the country politically, while allowing it to grow economically.

Working with Mitterrand, who also believed the threat of future conflict could be removed by tying the countries together economically, the two leaders were instrumental in shaping 1992's Maastricht Treaty, which officially created the European Union and began the process of establishing a monetary union.

"We all know this: the two happiest moments of our recent past, European union and German reunification, are also his life's work," Chancellor Merkel wrote in the Bild newspaper in 2015 to mark Kohl's 85th birthday. "I would wish that Helmut Kohl can look back with satisfaction on his great political legacy. Germany has much to thank him for."

As the unified Germany continued to struggle to integrate economically, rising voter discontent about high unemployment, coupled with a perception that the chancellor had grown stale, eventually led to Kohl losing to Gerhardt Schröder of the SDP in 1998 elections, ending what Schröder himself has described as "the Kohl era."

Caught up in a controversy concerning the CDU's acceptance of illegal campaign contributions, Kohl's final years in politics were tarnished by scandal, with former protégée Merkel largely disassociating herself from him. However, Kohl remained a Bundestag member until 2002.

His wife, Hannelore, who married Kohl in 1960 and gave birth to two sons, committed suicide in 2001 after suffering from an allergy to light for many years. In 2008, Kohl married Maike Richter, a woman more than 30 years his junior.

In 2013, following their father's 2008 stroke, his sons, Walter and Peter Kohl, accused Richter of "imprisoning" the former chancellor in their home and managing all his affairs. The Kohl sons accused Richter of being obsessed with their father for many years in the manner of a stalker. Writing of briefly visiting her apartment in 2005, Peter Kohl described it as a "private Helmut Kohl museum."

After a falling-out with Kohl's new wife, writer Heribert Schwan published an unauthorized biography in 2014 on the former leader based on transcripts of interviews the pair had conducted in the early 2000s. The discussions, which many assumed were not intended for publication, saw Kohl blast Merkel, who grew up in East Germany, for her perceived lack of knowledge of European politics and alleged inability to properly use cutlery.

Having grown increasingly frail and largely unable to communicate, Kohl's final years were largely spent out of the public eye. To many Germans, though, despite being buffeted by scandal in his later years, Kohl remained a symbol of their country's emergence from postwar ruin and an existential identity crisis into a confident, modern economic giant.

In honoring him with the Presidential Medal in 1999, Clinton said that Kohl had left an indelible impact on modern Europe and belonged in the pantheon of the 20th century's great leaders, alongside Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Charles de Gaulle. "For unifying Germany and Europe, for strengthening the Western alliance, and extending the hand of friendship to Russia, Helmut Kohl ranks with them," Clinton said. "His place in history is unassailable."