In the beginning, it was scary, but it was also relatively simple: Stay home. Shut down. Wear a mask. Stay 6 feet apart. Get your shot.

Now, though, things feel a lot more complicated.

You can get together safely with vaccinated loved ones over the holidays, but maybe you should reconsider. Omicron appears to be more infectious, but less deadly; though you should still worry about Delta, which is less infectious, but more deadly. Schools are still open — until they’re not, sometimes not even virtually. Social media is full of posts from friends either out partying or at home quarantining. Please still wear a mask in public, but not a cloth one, even though it’s still common to exercise in most gyms without one altogether. Rapid tests are useful but hard to find and maybe not so useful after all. Fully vaccinated means two shots, but also get your booster. If you have COVID but don’t have symptoms you should isolate for 10 days — no, wait, it’s five now — but then only reenter public in a mask if you can test negative, but also if you can’t find a test, that’s OK too.

As Americans prepare to enter their third straight year of the coronavirus pandemic, clarity feels hard to come by for many.

“Honestly I’m more confused now than I was all of 2020,” said Luis Luna, a 28-year-old advertising accounts manager in Austin. “So many friends and family got infected in December, and everyone had different symptoms. It’s just hard to keep up with instructions from the CDC and most government agencies.”

“I’m an architect. I should be able to design my way out of this mental labyrinth, but I can’t,” she said. “Can you?”

Ileana Schinder, an architect in Washington, DC, was in tears as she described the stress and concern she has for her two young children who are lurching back and forth between classroom instruction and remote learning with each new outbreak in their class. Schinder, 45, said she feels hollow and exhausted, as if she’s run a marathon in pursuit of a bus that keeps driving forward one block at a time, over and over. “I’m an architect. I should be able to design my way out of this mental labyrinth, but I can’t,” she said. “Can you?”

The world looks markedly different than it did when COVID first swept and shuttered the globe. There are now multiple vaccines that are safe and effective at preventing serious illness. More than 4.6 billion people around the world have had at least one shot. We know infinitely more about the virus, including how to test for it relatively cheaply and easily. We have new lifesaving treatments. “This is not March of 2020,” President Joe Biden assured a weary public just before Christmas. “Two hundred million [Americans] are fully vaccinated. We’re prepared. We know more. We just have to stay focused.”

And yet as Omicron now infects record numbers of people globally, filling up hospitals and closing businesses and classrooms, there is a lingering and strange sense of déjà vu, even if it also feels different this time.

“Earlier in the pandemic, I was actually really scared I could end up killing my mother. That was a very real fear,” said Allison Clough, a 50-year-old mother of two teens in the Bay Area who asked to be identified by her middle name so as not to embarrass her kids. “I don’t think that’s very likely anymore. I don’t feel scared in that way, but it’s ruining our lives again. I guess it’s kind of confusing.”

As regular people struggle to make sense of this point in the pandemic, experts are also wondering how we got here — and how we haven’t done a better job of preparing for it. “We’re in a difficult time. We’re in a strange time,” said Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “We’re in a time where we’ve had two years of experience with this disease, with this virus, and it continues to evolve … But as it evolves, we’re still in many ways kind of chasing it.”

“Many people have no idea what to do about something simple like masking.”

Arthur Caplan, medical ethics director at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, was far more blunt and sweeping in his assessment of the current state of confusion. “I would say we’re in a cacophonous, disorienting, deteriorating mess,” he said.

“Many people have no idea what to do about something simple like masking,” he continued. “Huge numbers of people are frustrated by the complete failure to provide adequate amounts of test kits. Parents are furious they’re not getting consistent policies that should have been planned weeks ago about what happens to their kids. Messaging from the CDC and other government authorities has become a mishmash of confusion for many people. Most people I talk to don’t know what fully vaccinated means and no one seems to be helping them understand it. And the internet is awash with escalating misinformation and conspiracy content.

“Otherwise,” Caplan joked, “things are good.”

It is somewhat inevitable that the pandemic and people’s decision matrix have become more complex, given both the evolving nature of affairs and the virus itself. Even before the Omicron variant emerged, requiring yet more study and analysis, people around the world were already trying to adapt their lives around COVID. Workers were returning to offices. International borders had reopened. People were dancing in nightclubs again, albeit in many places that check vaccine cards at the door. We got to celebrate Thanksgiving.

Omicron then arrived at a time when each person’s perception of risk was already changing, at an inflection point in public thinking. After a summer dashed by Delta, many had already begun to imagine a world where COVID would be with us for quite some time. The new variant’s incredible infectiousness, and apparent relative mildness for vaccinated individuals, has only seemed to deepen a sense of inevitability for many people. As comic Isabel Hagen joked, “Making plans in 2022: I can’t get covid this week, but I could next week?”

“It’s with us. It’s omnipresent,” said American Medical Association President Gerald Harmon. “We’re trying to adapt to that and we’re trying to avoid being overrun, not only in our day-to-day lives but in our healthcare systems.”

“We want to have this in the rearview mirror and we can’t quite get there,” Harmon said. “It always seems to be alongside us in the passing lane, and every now and then it gets ahead of us.”

The AMA was especially critical this week of the CDC’s evolving guidance on quarantine and isolation, which has seesawed on whether a negative test was necessary for asymptomatic people to reenter public life after five days. The guidance has even confused US senators. CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, whose communication skills have come under intense scrutiny, had defended the decision by arguing the tests don’t definitively show whether someone is still infectious, but large sectors of the public have not been able to keep up with this nuance.

With an unmistakable sense of incredulity, Harmon released a statement on Wednesday in which the AMA president appeared aghast at the CDC. “Nearly two years into this pandemic, with Omicron cases surging across the country, the American people should be able to count on [the CDC] for timely, accurate, clear guidance to protect themselves, their loved ones, and their communities,” he said. “Instead, the new recommendations on quarantine and isolation are not only confusing, but are risking further spread of the virus.”

Harmon told BuzzFeed News his intention was not to assign blame and that he still has trust and confidence in the CDC, but that he felt a duty to speak out at what he saw as mixed messaging. “When I see something that’s a little bit incongruent, it makes me a little bit uncertain,” he said.

In defending the CDC, one prominent scientist who spoke with BuzzFeed News — but asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of the questions — said they believed there is a “false assumption” that experts are all-knowing all the time. “There’s this idea in the public that the knowledge is kind of static: ‘Just tell us what it is! Why are you waffling around?’” this scientist said.

“But the knowledge is accruing day by day and it’s going to change day by day as the data changes. It’s not something that can be reduced to one simple sentence because there’s all these ‘if not this, then that, and if not that, then this.’ It gets very geeky.”

“I don’t think the scientists and the public health experts are confused. But there is uncertainty,” they said, citing the unprecedented nature of the pandemic. “It’s a different thing, though, to not be confused and to know what’s going to happen. The scientists don’t know what’s going to happen, but they’re not confused about what does happen.”

For regular Americans, though, it has been somewhat hard to keep up. “In my opinion, the CDC has been frustratingly unclear on defining a mask’s effect on determining close contacts,” said Roger Yamada, a 38-year-old attorney in New York City. “How do we assess cloth masks vs. surgical masks vs. KN95/KF94/N95 masks? Or does it not matter at all?”

“More than anything it’s just annoying,” said Daniel Golson, a 28-year-old social media editor in Los Angeles, who with his friends is navigating the maze of testing and isolation guidelines after an outbreak among some of them on a New Year’s trip to Montana. “I want to do the right thing to prevent me from potentially infecting others, but I also don't want to unnecessarily spend money to have to stay in a place and not go home if I don't need to.”

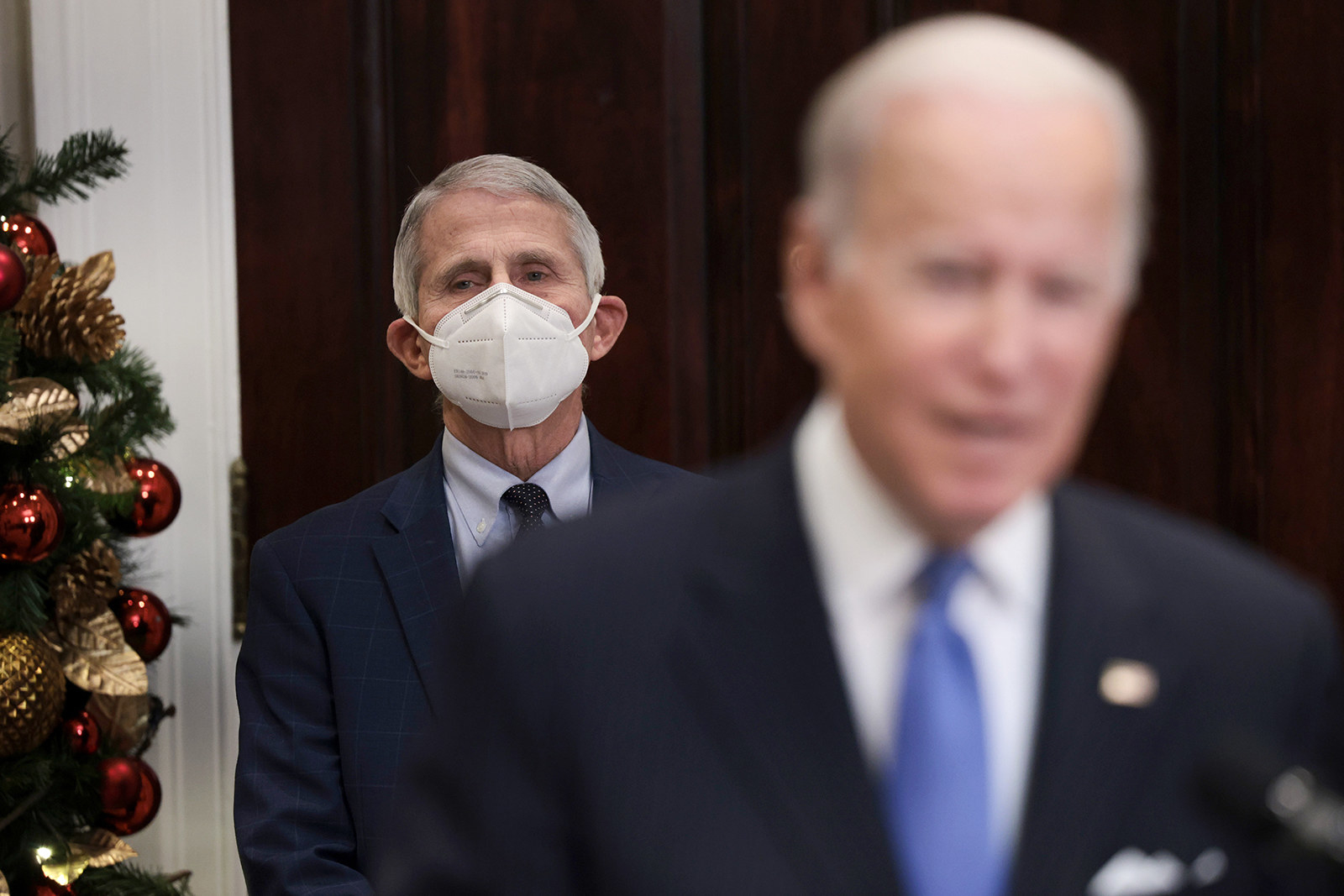

Public health officials have been clear that this Omicron wave is not like previous surges. Top White House medical adviser Anthony Fauci has said it was “very prudent” for the CDC to try to change its guidance based on the emerging data on the variant’s transmissibility and period of infectiousness, in order to try to avoid massive staff shortages across every industry and effectively keep society running. Fauci also said this past weekend that the US was entering a new stage of the pandemic where hospitalizations, not total caseloads, should be the focus of public attention.

But the prominent scientist said it was evident there was something of a fissure between experts and the public. “The American public has become over decades science illiterate,” they said. “Scientists tend to talk in a different language than regular people can understand. It’s kind of a mismatch between those who communicate and those who want to be communicated with not talking the same language.”

“The American public has become over decades science illiterate.”

Caplan, the NYU medical ethicist, said he believed that due to this scientific illiteracy, it was natural that people have become confused, even angry, by the shifting messages. “If you have lousy training on critical thinking and scientific methods in your high schools and junior high schools then it’s no accident that citizens don’t know how to interpret what’s going on in a plague,” he said.

Clough, the Bay Area mother, said her friendship circles seem torn in two by those who are afraid and still want restrictive measures and those who are resigned to trying to live in what they feel is their new reality. “Some of my friends are worried school closures are going to be a drag and others are still afraid they’re gonna die,” she said. “It’s a little hard to navigate between all that.”

Tensions are also high in her community, where whether or not your children will be in class can depend on a county line. Everyone she knows is vaccinated, including her kids and their friends, but there seems to be politics everywhere. She’s noticed people again walking solo on the beach but still wearing a mask, which she thinks they’re doing as some sort of statement. She said she was accused of wanting to murder teachers when she raised a statistic about the extremely low risk of children becoming extremely ill or dying from COVID. “Just looking at the numbers, the chance that even without the booster shot my 13-year-old is going to end up seriously ill is vanishingly small,” she said, “but it’s become so politicized in my extremely liberal community that it’s almost like some people want to hold on to the possibility of that against all this data.”

In DC, Schinder, the architect and mother, begrudgingly admitted she’s even begun to question her own Democratic politics when she looks with jealousy at photos of friends’ children in Republican-led states where schools have stubbornly stayed open through most of the pandemic. How is it fair, she wonders, that her city’s leaders seem to be prioritizing people’s right to go to bars over her kids being in a classroom?

“What pains me is we’re still adapting every decision to those that effectively decide to ride bicycles without a helmet.”

“If you’d have told me that two years down the road my kids wouldn’t be in school, I’d have thought that we didn’t yet have a vaccine, a health solution. But we’ve moved on from that. We have a health solution,” Schinder said. “What pains me is we’re still adapting every decision to those that effectively decide to ride bicycles without a helmet, to those that ride in cars without seatbelts. I think it’s time to move on.”

A group of former Biden expert advisers might agree with her. Six scientists who served on the president’s transition health advisory board on Thursday published a series of opinion pieces in the Journal of the American Medical Association calling for the administration to now focus on what they called “the new normal of life with COVID.” Omicron, they said, had “created concern about a perpetual state of emergency.”

They advocated, among other things, for changes and improvements to testing, vaccine mandates and technology, and data collection. But more than anything, they said the focus needed to be on the future, not the cloud of the current crisis. “We think a lot of work still needs to be done to see through that smoke to see how this is going to end, and start laying down steps for how we will be able to live a normal life,” one of the scientists, Rick Bright, told the New York Times.

Both the APHA’s Benjamin and the AMA’s Harmon said they also felt more of a focus on modeling was needed to better predict and respond to future iterations of this virus and others so as to avoid more chaos. That could include extensive new investment in public health infrastructure and preventative medicine, such as vaccines.

“The nature of the virus is unpredictable, but that’s the nature of any enemy,” said Harmon, a retired Air Force major general. “Using a military analogy, we need to not fight the current war or previous wars, we need to plan for future engagements. We need to think of asymmetric warfare with this virus.”

Still, Harmon said, right now an urgent challenge is to try to reach those weary soldiers on the homefront who are finding themselves, like Clough in the Bay Area, struggling to see the way forward.

“Even when things seem nutty, I don’t have the energy to develop strong opinions and advocate for them like I did in the first shutdown,” Clough said. “I can’t muster the same passion for it that I had earlier. I feel tired. I feel a little bit resigned to whatever is going to happen.” ●