Decades after they fought for a seat at the table inside the Democratic National Committee, black women political leaders say their allegiance to the institution they helped build is now critically imperiled, citing an exasperation with chair Tom Perez and a widely shared feeling that the party’s central arm gives only superficial recognition to the voices that represent its longest-serving stewards and most loyal base of voters.

From young officials to veteran operatives, black women in the party described the DNC of 2018 as “unrecognizable” — less “open,” they said, than in the era that ushered in the Jesse Jackson presidential campaign of 1984, made Ron Brown the first black Democratic chair in 1989, and installed a generation of black women at the highest levels of the party for the first time.

Now, as the party remakes itself amid an election that could see a wave of victories for candidates of color, those original black leaders say they feel pushed aside.

“Ron Brown would be rolling over in his grave,” said Yolanda Caraway, a longtime Democratic official who helped Brown get elected, served as a DNC member for some two decades, and worked inside the party in such roles as director of the DNC’s Fairness Commission in 1985 and vice chair of the Democratic National Convention in 2000.

“It just breaks my heart. I don't feel I'm included in this party anymore,” Caraway said. “I'm, like, three weeks away from going to register as an independent. I really am.”

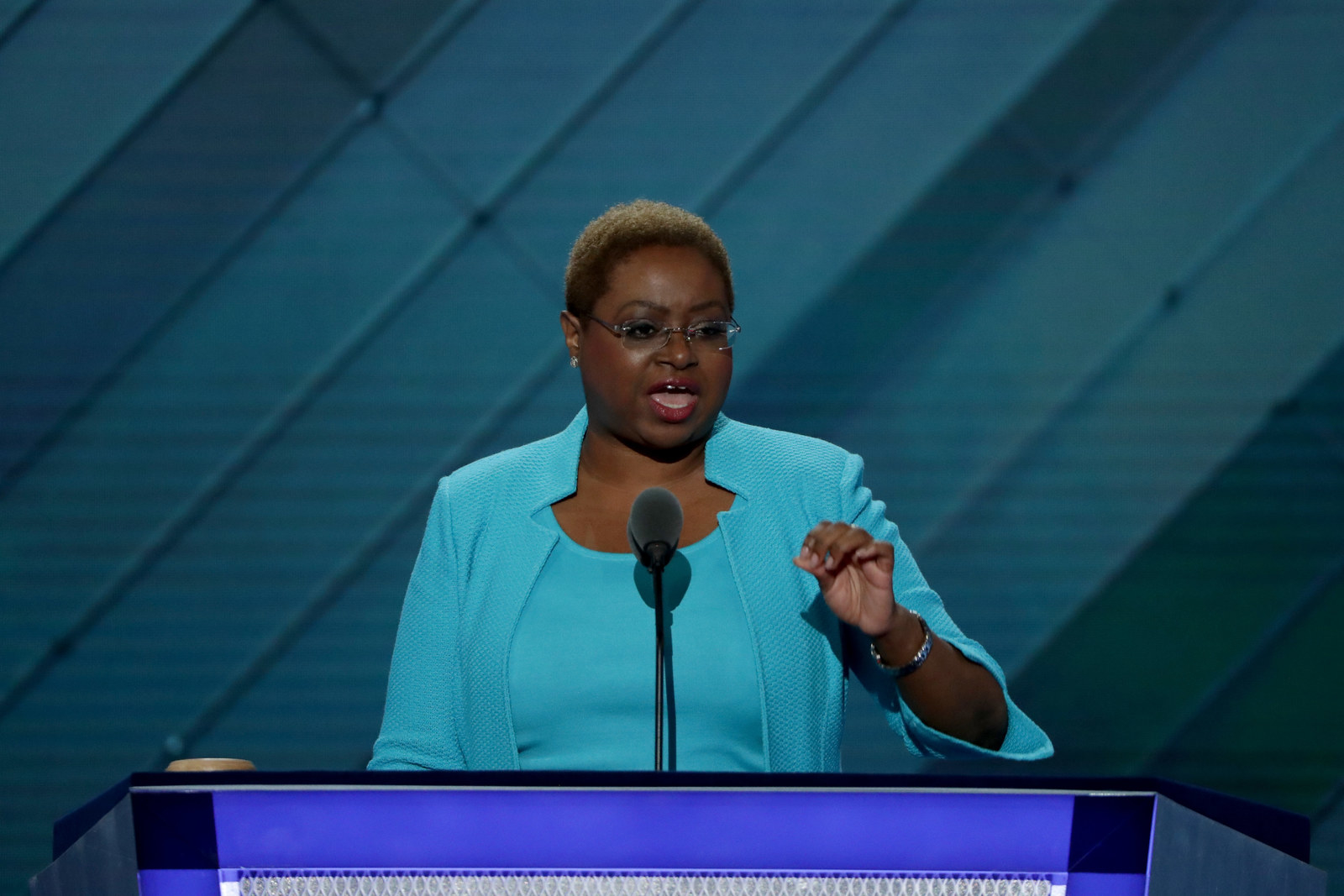

In interviews over the last month, black women across the party ticked off a litany of concerns and complaints about the DNC’s leadership under Perez that have been mounting in a “slow burn” since his election 18 months ago, according to Jehmu Greene, a 46-year-old Democratic strategist and commentator who served on Perez’s transition advisory team last spring.

They say the DNC doesn’t elevate black women as public spokespeople or behind the scenes. (Early on in Perez’s tenure, they wrote an open letter to their new chair to express concerns about his staff hires and “the absence of our inclusion in discussions about the party’s forward movement.”) They say Perez, a former labor secretary in Barack Obama’s administration, has an impressive resume in government service but lacks the kind of political appetite and experience that, in their view, made Brown an inclusive and commanding party chair. (“He’s not political,” Caraway said of Perez. “You either are, or you’re not.”) And they say that when they’ve raised these questions with Perez and his team, they are largely brushed off. (Greene took the public step of publishing an op-ed to call attention to the fact that black women are “ghosting the Democratic Party.” The DNC did not reach out after it ran, she said.)

Black women in or close to the party refer to the problem at the DNC in impassioned, at times emotional terms: People are “heartbroken,” they say. “Fed up” and “disgusted” and “appalled.”

“The weight for addressing these very real and growing concerns falls on Tom Perez as leader of the party,” said Leah Daughtry, a longtime operative who has worked in and around the DNC since the ’80s and headed Perez’s transition team. “He often says that black women are the backbone of the party, and folks appreciate that sentiment. But women are looking for the evidence that it’s more than words.”

“I think a lot of women don’t see that evidence, so patience is wearing thin and frustration is getting high,” Daughtry said.

In response to the concerns laid out in this story, DNC officials pointed to a number of black women working in key staff roles, including chief operating officer Laura Chambers, political and organizing director Amanda Brown Lierman, and director of African American outreach Waikinya Clanton. They also argued that Perez has worked to engage black voters on a more consistent basis than in prior elections — through investments in black women candidates, like Stacey Abrams in the Georgia governor’s race, and with the launch of “Seat at the Table,” a new program aimed at black women led by the DNC’s women and black caucuses, along with the Congressional Black Caucus PAC.

Brown Lierman, who joined the DNC last summer, said she’s never worked in a place “with as many people who look like me on a daily basis.” But she also acknowledged that the party could be doing a better job. “There’s no doubt there is more to do,” she said. “It’s really helpful to have that external pressure and accountability in place to make sure that we are always striving to do more.”

If the “slow burn” began with the open letter last spring, then it intensified into a deeper dissatisfaction this summer after Perez let go of Daughtry, who ran the Democratic National Conventions in 2008 and 2016 and, until this summer, had been leading the DNC’s 2020 convention planning. For other black women in the party, it was a stunning decision. It felt personal, with implications far greater than Daughtry, her contract renewal, or any single personnel decision.

“How can they say that black women are the strongest voter base of the Democrats and then cast all of their experienced people to the side?” said Alice Huffman, who is the president of the California NAACP and has been a member of the DNC since 1988. “It doesn't make sense to me.”

It did not help matters, many of the women interviewed for this article said, that Perez replaced Daughtry with his former chief executive at the DNC, Jessica O’Connell, who is white.

“It's kind of like a line's been drawn in the sand,” said Caraway. “This might be the nail in the coffin as far as black women are concerned.”

Donna Brazile, who has twice served as the DNC’s interim chair, said she wasn’t consulted about the decision to move on from Daughtry. She did, however, echo other top Democrats’ assertion that when it comes to process knowledge regarding convention site selection, and planning and execution of the event itself, “There’s no better person than Leah Daughtry.”

“I have a tremendous amount of respect for what has to happen at the DNC, especially when you do not have a sitting Democratic president,” said Minyon Moore, another veteran party operative. “But when the noise started around Leah, it gives you pause.”

DNC officials said that in the convention planning process, which is typically run in three distinct phases from site selection to the actual planning of the event, it’s not unusual to place different operatives in charge of each phase. In 2016, they noted, former DNC CEO Amy Dacey ran the site selection process before Daughtry stepped in to serve as CEO of the convention itself.

The Daughtry decision was nevertheless a frequent topic of discussion among Democrats at their annual summer meeting last month in Chicago. The frustration spilled out into the open on the floor of the general session, when DNC members voted to drastically scale back the superdelegate system, which used to grant about 700 party leaders their own delegate to award to the presidential candidate of their choosing. In a series of tense speeches, some longtime DNC members argued that disempowering superdelegates in the nominating process — a priority for Bernie Sanders supporters — would effectively “disenfranchise” some 200 black superdelegates.

“Are you telling me that I’m going to go to a convention — after my 30 years of blood, sweat, and tears for this party — that you’re going to take away my right?” asked Karen Carter Peterson, the DNC’s vice chair of civic engagement and voter participation.

Huffman, the longtime DNC member and NAACP leader, said she made a number of attempts to reach out to Perez over the last year and a half. It wasn’t until a conference call this summer, when she expressed her objection to the superdelegate change, that he got in touch with her, just to try to sway her vote, she said. “I don't think he knew I existed until that,” Huffman said. “He never responded to anything in the past.”

In the weeks since the vote in Chicago, the debate has continued inside the party. “Now that POC, women, and LGBTQ+ leaders have a significant say in the nomination process suddenly the rules need to be changed, effectively eliminating their participation. Funny how that happens,” Daughtry tweeted after the meeting.

“Amen,” Brazile wrote in a USA Today op-ed late last month, quoting her colleague’s tweet. “I earned my place at this table. Hell, I helped build the table. So when you’re sitting at it without me, please use coasters. I don’t want any stains on it.”

Brazile, Daughtry, Caraway, and Moore count themselves among the generation that, alongside leaders like Jesse Jackson and Ron Brown, helped pave the way for black women inside the party in the 1980s. “Jackson ’84 made us part of the ‘they’ of American politics,” the four women write in their upcoming coauthored book, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Politics. “That was the presidential election where we got our first real taste of being in the room where it happened.”

Before that, it was different.

The 1964 Democratic National Convention marked a turning point in black women’s quest for equality in US politics and the Democratic Party. As part of the culmination of that year’s Freedom Summer registration drive for black voters, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party led a delegation to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. The goal was to replace the state’s all-white delegation in a summer that had seen the murder of civil rights workers Mickey Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman. Those who testified before the DNC’s credentials committee included Martin Luther King Jr., Schwerner’s widow, and a sharecropper and organizer from Sunflower County, in the Mississippi Delta, named Fannie Lou Hamer. She testified that after she went to register to vote in 1962, three white men came and told her that they planned to make her wish she was dead. They instructed two black men to beat her — all because she sought to register people, and herself, to vote. “If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now,” she testified, “I question America.”

The party’s concession that year was two seats for the more than 60 of them, including Hamer, who responded, “We didn’t come all this way for no two seats when all of us is tired.” The DNC’s refusal to seat the group is a blot on Democrats’ record on equality and the kind of injustice the party has since tried to correct.

Hamer treated the party in the following years as being separate from herself. In testimony to the Democratic Reform Committee in 1969, she pointedly referred to the party and its officials in the third person, as noted in the book, The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell It Like It Is.

Hamer had hard things to say about the state of black women’s position in the party, and there was “no question” she would raise her voice about it, said Davis W. Houck, a professor at Florida State University who coedited To Tell It Like It Is. “Her whole thing was speaking truth to power,” said Houck.

Perez frequently brings up Hamer when talking to black audiences. But despite years of work from black women inside the party, some of Hamer’s criticisms still hold. “I get what [Perez is] trying to do, which is to call attention to a past when black women tried to lead the party in a new direction,” said Houck. “But,” he added, “to just drop her name, that’s not really doing anybody any real good. She’s not a simple person with a simple legacy and it empties her of a lot of her complexity. And it’s insulting to her.” Additionally, he offered that Rosa Parks, who Perez often mentions in the same breath as Hamer, did not do politics. “It’s like, come on now. There are black women in history who did politics and did it well. We got to learn some new names.”

Hamer’s early activism was about voting rights, and then later, in the 1970s, focused on food access and eradicating poverty and not necessarily as centered on activity in the Democratic Party, whose engagement she in 1968 compared to a mother who can’t properly tend to her child and resorts instead to a pacifier. “And that's what we have today,” said Hamer of the party’s efforts to listen to people’s ideas on reforms, “something that really didn't do us any good, but just get us to hush.”

That is how some women in the party view the DNC’s A Seat at the Table tour. (A Facebook group for the initiative was invite-only, one national operative noted.) Billed as a national listening and training tour, the forum is led by Waikinya Clanton, the DNC’s black American outreach director, and its logo includes images of three political icons: Hamer, Shirley Chisholm, and Barbara Jordan. “We do what we do because we know there is a history of marginalization and of abuse in this nation,” said Rep. Yvette Clarke of Brooklyn, where the first event was held. Brown Lierman also gave remarks at the event, saying black American women “are the table and we invite the rest of the country to sit there with us.”

These highlights made it into a glossy video the DNC played to an audience at a recent Atlanta fundraiser. “We took too many people for granted and African Americans, our most loyal constituency, we all too frequently took for granted,” Perez said in Atlanta. “That is a shame on us, folks, and for that I apologize. And for that I say, it will never happen again!”

Black women say the program is needed but not groundbreaking, describing it as “window dressing” and “insufficient” to rebuild black women’s trust in the party. Most of all, they worry it’s being interpreted as an unprecedented step for the party, which in the past sponsored significant outreach to black women under former DNC chairs like Brown, Terry McAuliffe, and Howard Dean.

“We don’t need you to set a table for us,” said Melanie Campbell, the president and CEO of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation and the convener of the Black Women’s Roundtable Public Policy Network. Campbell, a longtime organizer, has reinvented herself as a powerful central figure in a wide-ranging effort to magnify black women’s voices in the digital age. “It’s not about apologizing to us. It’s about recognizing if you want to win, black women are who is going to drive it.”

A young black woman who is a popular Democratic political operative and activist said Clanton is well-liked and respected, but “a lot of people are trying to understand what [A Seat at the Table] is.” In April, there was a pivotal meeting about the DNC’s engagement with black women, according to a person familiar with the gathering. Exposing internal problems, the Colored Girls coauthors, four women seen as mentors who helped transform the Democratic Party, were not invited, three sources said. A Facebook group for Seat at the Table “ambassadors” run by Clanton remains closed with just under 1,000 members.

The young black operative, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity because she did not want her opinions to reflect on her organization, echoed the sentiment of nearly a half-dozen of her peers: Her generation hasn’t yet parsed the irony that it’s walking through doors opened by women who feel locked out of a political apparatus they built in a society that subtly and systemically devalues their labor. “The only reason that I’m here and that I know I can do this is because of them,” the operative said.

“You see black women changing the face of this party by taking political power at all levels. You see women like me in all corners of this political ecosystem. That’s because of what they have done to clear a path for us. It’s a small consolation, but I guess we have the added benefit of time. At some point the party has no choice but to listen and invest in us. Right?”

DNC officials asked Valerie Jarrett, a former Obama senior adviser who has, they said, been advising Perez since his election last year, to speak on behalf of his efforts to increase black voter engagement. “Under Tom Perez’s leadership, the DNC has engaged African American women in the political process and voter turnout with clear, demonstrable results,” Jarrett said in a statement, pointing to candidates like Abrams and Illinois’s Lauren Underwood.

Jarrett did not address the complaints among black women operatives about their representation inside the party apparatus.

For those concerned about the DNC, the question now is how best to move forward. There is talk about another open letter to Perez. For Greene, the commentator who sat on his transition committee, it’s about seeing “specific and expedited decisions about the visibility of black women in leadership roles at the DNC,” she said. “I don't see them. I don't hear from them. I don't see their voices being amplified.”

But most agree that a sit-down with Perez should be an urgent priority.

“We should really have a face-to-face with him,” said Huffman, the NAACP leader.

“There is a real come-to-Jesus moment that needs to happen with Chairman Perez,” Greene said.

Groups like Higher Heights for America, which is run by black women, and the Collective PAC, which supports black candidates and is co-led by a woman, have robust black women leadership. And yet, for all of their successes as relative newcomers to US politics, their momentum reflects another irony: that something makes their existence necessary.

The same could be said for another new group, Power Rising. Last February, a group of women from various sectors, but mostly politics, convened the Power Rising Summit in Atlanta, long the urban avatar of black American progress in business, culture — and politics. The group released a promotional video in stark contrast to the DNC’s “A Seat at the Table” digital spot, featuring women showing little emotion, all reciting Maya Angelou’s legendary 1978 poem “Still I Rise.”

The group isn’t a political organization. One session, however, did cover political organizing in the digital age, in a summit where the theme endorsed the notion that anyone in 2018 who ignores, demeans, or devalues black women will pay dearly. Power Rising wants to build a black women’s agenda and, like so much of black women’s contemporary activism, a Hamerian legacy — an example of how black women can turn power into action.

Remembering Hamer, Houck recalled how in 1964, along with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, she, too, had come looking for a seat at the table.

“They did everything right and by the book — and then they get got trumped by party politics,” he said. “They were in the right, and they were wronged by the power players of the party.” ●

CORRECTION

Laura Chambers is the DNC's chief operating officer. An earlier version of this story misstated her title.