Early on the afternoon of May 14, the day his presidential campaign announced a plan to reduce the number of gun suicides in America, Cory Booker, who was in Washington, DC, on Senate business, slipped away to meet with a group of young black leaders handpicked by his campaign. The invitation was thin on details; a week earlier, Booker’s campaign team sent the group of civil rights activists, clergy, and elected officials a terse email with the subject line, “Black millennial leaders meeting with Cory.”

It was early in the presidential primary, but Booker was languishing in the low single digits in national polls, even after a seamless performance in a CNN town hall at the end of March that, according to one associate, had a few people in Booker's orbit, who had been skeptical about his prospects, re-evaluating the field's political talent. Booker was praised for his proposal to reduce gun violence, and around the same time, he cosponsored a bill to address black maternal mortality rates that are four times higher than those of white mothers. But the polls didn’t budge. So Booker began to test another message, one designed both to inspire undecided voters and to assuage the concerns of primary voters still rattled by Donald Trump’s 2016 victory: Simply beating Trump (“removing one person from one office”) was the “floor, not the ceiling” of what Americans can do.

Now, in Washington, Booker was seated at the head of an ornate, rectangular table, freshly-shaven and dressed in a dark suit and red tie. Together, he and the young leaders discussed "candidly," according to multiple people who were in the room, the suddenly dizzying array of problems, tensions, and shortcomings that arose with the campaign's effort to reach a younger, national black audience. Booker was energized as the meeting shifted to tactics that had fueled his rise in politics: simple, detailed ideas to attract attention at the grassroots level.

He was told to lean into his biography as a son of the civil rights movement, encouraged to relate himself as a shepherd of a majority-black city that he never left. Someone wondered what if Booker used social media to lead a constructive, modernized conversation about race in America, drawing on the perspectives of young activists to educate and empower his white supporters unclear about what they should be doing. If done right, the young leader believed, the forum could also serve as a tool to build community and engage his white supporters.

But then Booker’s appearance on The Breakfast Club became the prime example of what the invitees saw as Booker’s quandary.

In February, a few seconds into that radio interview, host Charlamagne tha God asked, “Does Cory Booker have a specific agenda for black people, and if so, what is it?”

Booker laughed, then launched into a well-meaning, but unfocused love letter to black people. He identified himself as an African American and a black person; he referred to black Americans as the “conscience of this country since its founding.” He said the black experience had “challenged the inadequacy” of the words describing America as a nation with liberty and justice for all.

“And so right now, you pick an issue from maternal mortality rates to incarceration, the broken criminal justice system, to access to health care — you see African Americans having worse outcomes, and you address the issues of Americans, how are African Americans — the very promise of America becomes real.

“And let me give you an example of this … ”

What about the agenda? Charlamagne asked a second time.

“I have a specific agenda for the American people.” There was more back-and-forth, and then Booker offered another example with a rationale that fixing big problems helps poor white people, but also black people disproportionately affected by injustices.

Booker eventually recovered, but in the weeks after the interview, Charlamagne expressed support for Kamala Harris. Booker’s young audience in Washington found his answer to Charlamagne’s direct questions devoid of the compelling nature of his biography.

The Breakfast Club was “the perfect opportunity to say who he is and what he’s done to a target audience, and he went in like, ‘Cool, this is who I am, y’all know me,’” said Brenton Brock, one of the young leaders at the meeting. “But in that setting, you need more. White spaces, you get a leg up, so you don’t need to announce that because you’re black — they know what you’re about. We need more in black spaces.

“He thinks people know who he is.”

Hadn’t Booker’s years of public service — from the Newark City Council to the US Senate — established him at or near the top of the List of Prominent Black Leaders in the post-Obama era? There’s a world you can imagine where a candidate like Booker would be running strong with younger voters, especially young black voters. Research, such as a recent report titled the Black Millennial Economic Perspectives Report, published just this month found 36% said criminal justice was their top domestic issue — a top Booker issue. (A similar study from two Democratic PACs found that "despite having every reason to be disenchanted with politics and the political process, unregistered black millennials remain aspirational and committed to protecting and empowering their families and communities.”)

But Booker didn’t have strong black support in the race the moment he jumped in, and he can’t bank on it coming later. There is another leading black candidate in the primary, and that’s to say nothing of the high levels of support right now for Joe Biden, or the affinity for Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders among some younger black activists and voters.

His speeches are eloquent, timely. He’s had moments in debates; shown flashes on the trail; built up an impressive organization in Iowa; constructed a clear policy agenda on guns, criminal justice, and marijuana. Dressed in a dark tie — such as when he was speaking in Selma, Alabama, on the anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday” march from Selma to Montgomery — Booker cuts an impressive figure. And he is Cory Booker: the Rhodes scholar who moved to Newark, New Jersey, and took on the Democratic establishment, the mayoral candidate who wouldn’t quit, the senator who passed significant criminal justice legislation, the almost-VP candidate who people thought would be a lock to be a presidential frontrunner. Ask them at events, ask them in polls — a lot of Democrats like Cory Booker; they just don’t seem to love him, at least not yet.

“It was like we were speaking to our big brother running for president who was still trying to figure out his lane in this race.”

“People are still getting to know me,” Booker has often said this year.

For his young supporters that day in Washington, the message Booker communicated unintentionally was clear. “The vibe was different from what you might expect from meeting with someone who is running for the highest office in the land,” said Stephen Green, a 27-year-old African Methodist Episcopal pastor from New Jersey. “It was like we were speaking to our big brother running for president who was still trying to figure out his lane in this race.”

One attendee said they thought Booker felt like he was at a crossroads with white millennials and black folks as a whole. At one point, the room told him they wanted him to be more forthcoming about the things that make him and not, say, Sanders or Warren their champion.

“People are proud of you just for being you,” the person remembered saying, echoing others in the room who said Booker looked as if he appreciated the pep talk.

“Who he is is good enough. I mean, before this presidential race, who didn’t want to be in a room with Cory Booker?”

In Newark, people get Booker. He invited me to his adopted city in May. He’s said that touring the neighborhood was part of his campaign’s press strategy. Other stories, though, did not quite capture what I had seen: a group of young men hanging on a corner haranguing him about what it was like running for president, women driving by and telling him that he had better win the nomination and beat Trump.

The tour in Newark stopped at a new school, at a former dumping ground that is now a large municipal park, at the police precinct where the 1967 riots began, and at a soul food restaurant, Vonda’s Kitchen, where the vegan Booker ordered me the catfish and told me that I had to try the macaroni and cheese. At Vonda’s, he filmed a video for a younger man who said he was out of work and looking but couldn’t find anything. He asked him what he does and then filmed a video talking about this “strong brother” who was down right now but hopeful and optimistic that he’d rebound.

Booker hangs a large map of Newark in his Senate office. The city is central to his story, even though he didn’t grow up there himself. In the spring of 1969, two adult children of sharecroppers who marched had a son in Newark’s wealthy suburbs who would be elected as a ward council member in 1998, as mayor in 2006, and as the country’s fourth popularly elected black senator in 2013.

In between, Booker became a national politician, someone known for exuberance and an attentive, on-call mayoralty in the early part of this decade. When he first decided to run for Newark’s City Council, Booker got the support of the late political activist Carl Sharif, a perennial candidate who instructed his young charge to knock on every door, trusting that people would respond to him being authentically himself. “[Sharif] knew that this quest would leave an indelible impression on me that would be the foundation of my political career as a council member and beyond,” Booker wrote in his memoir, United. “He knew that not only would residents feel me, but I would feel them, too, that I would more deeply believe in them, that I would bond with them.”

His ambition grated on his early opponents, some of whom thought he was using their city on his way up. In April 2001, Booker, then on the City Council, clashed with Newark Public Schools Superintendent Marion Bolden over a speech Booker had given to the Manhattan Institute the year before, in which he berated the city’s government and referred to the school system as “repugnant” while praising charters. Bolden wrote in a local paper that she was “deeply disappointed” with Booker’s “one-sided, extremely negative portrayal of our schools and community,” before listing a litany of strong accomplishments. “Nowhere in your presentation is there even a hint that any of this is taking place,” she wrote. Booker responded, writing that he found parts of her letter “simply disappointing” and defending his broader beliefs: “I criticize the system because ultimately it is not our children who have failed but it is our system that has failed our children.”

Back in the spring, Booker told me that he experienced early attacks that he wasn't "black enough" as "trauma." Booker's closest allies are eager to dismiss that narrative, too. “Cory Booker has the most actual lived black experience of any presidential candidate in American history. He is of full African-American parentage, and he has intentionally lived in an inner-city and personally grappled with these issues at every level of government in which he has served," said Donald Calloway, a Democratic political strategist backing Booker's campaign. "It bewilders me that anyone could question his blackness, or commitment to black issues."

But the ambition to lead a new generation worked for Booker as he moved up in Newark, and it’s part of his case now as he faces off against Democrats like Biden, a candidate who still has one foot in the 1970s.

Of course, Booker is happy to talk about what he accomplished in Newark — there were plenty of challenges, scars he sometimes wears in interviews as a badge of honor, evidence of his abiding love for the city. He says sometimes he got his PhD “on the streets of Newark.” While in South Carolina, he alluded to Newark as a destination for thousands of black Americans during the Great Migration.

Invariably, black politicians navigate spurious questions about their qualifications for office. Barack Obama actually benefited from a thin résumé; Hillary Clinton erred in the 2008 primary against Obama when her campaign and surrogates tried to characterize him as too inexperienced — voters read the attacks as racially motivated. (Notably, Booker was one of Obama’s earliest endorsers.) Booker won’t have that problem, but these days on the campaign trail, he is talking about his tenure as mayor of Newark not as a political victory but, rather, as a spiritual one.

At one point, when we were walking the city earlier this year, Booker visited a woman named Annie Finney. Booker knocked on her door with a pitter-patter knock that sounded like he was canvassing the neighborhood. “Everybody decent?” Finney let out a squeal when she saw him.

Inside, there was a framed picture of Booker, looking like the president of the United States, hanging on her wall. After Booker had talked to her for about five minutes, a small, frenzied crowd gathered at her doorstep. Someone told him they needed a job. (“I need one too; that’s why I’m running for president!”)

But even in Newark, the warm reception can be detached from exactly what Booker needs. A man holding a freshly lit joint a few blocks away motioned at him to come over and said he knew Booker was going to be president when he met him in 2000 because, in his estimation, Booker was “a scholar.”

“‘I said, they got plans for him. You gon’ be the president one day.”

Said Booker, “I hope that’s prophecy, man.”

“You ain’t gonna run this year?”

“I’m going to do everything I can to talk to the heart that I see in my neighborhood, the yearnings that I see in my community.”

This was months into Booker’s bid. The man went back to his Friday night, but not before telling Booker that he must have known that being a city councilor and mayor of Newark was a stepping-stone for greater things.

New Jersey, where Booker has earned a wide array of endorsements, doesn’t vote until June in the Democratic primary. Booker said the day “would be a great day for me if I’m still in the primary.” When I asked him if that meant he wasn’t afraid to lose the nomination, he looked downward for a beat.

“Oh, I’m running to win,” he said. “But at the same time, I’m more interested in my purpose than the ultimate position.”

He told me later that “punching Donald Trump in the face” just wasn’t his purpose. “That’s not what I’m going to be giving folks. And I’m going to do everything I can to talk to the heart that I see in my neighborhood, the yearnings that I see in my community.”

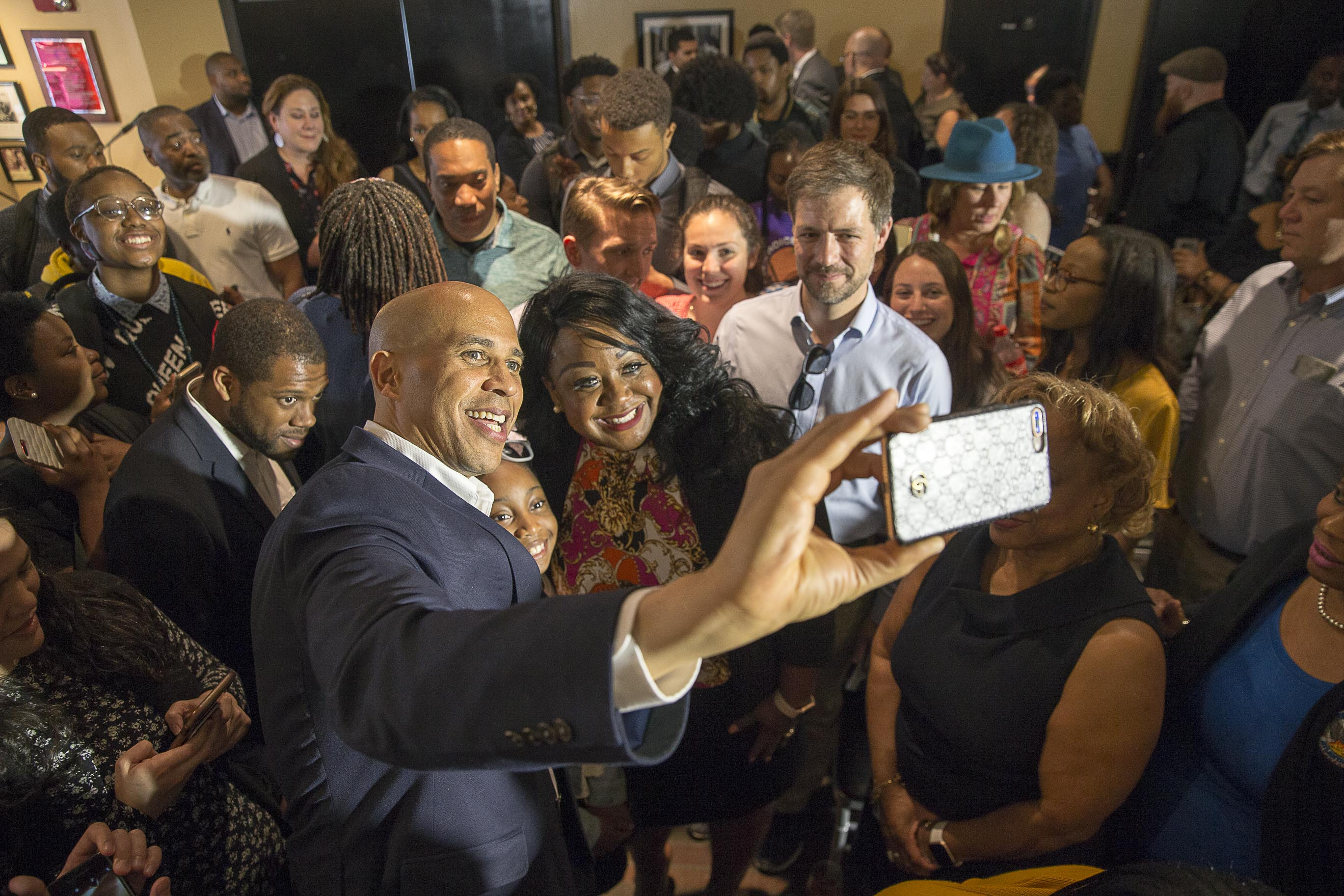

Booker’s political philosophy involves a particular belief about the community and a “restoration of civic grace,” rooted in the history of black America. He accents words like “compassion,” “empathy,” and “patriotism” with adjectives to create on-brand formulations like “courageous compassion” and “radical empathy.” He speaks in set pieces that he formulates, rehearses, and then commits to memory. His tone, pace, and phrasing are precise. When I saw him in April in Atlanta at Paschal’s, a soul food restaurant and signpost in the civil rights movement, he said things like, “I want to unabashedly talk to you for a moment about love.”

His audience, full of young political activists, applauded politely.

Still, his presentation that day resonated with Aliza Abusch-Magder, a high school student. When I asked what bothered her most about the political climate, she said it was the lack of basic respect for other people with different views. She agreed that Booker was right, that fighting “fire” with love, which she defined as “stubborn positivity,” felt to her like the only way forward. “We can try; I just don’t think anything else will be effective so that we can create meaningful lives for American citizens both in terms of policy and just day-to-day peace of mind.”

When I told Booker about my exchange with Aliza, he spoke excitedly about the parallels between the civil rights generation and the young people of today, and how a sense of urgency, idealism, and seriousness of purpose in the fight against injustice was the best hope for America. “I really do think this generation has the potential to be that kind of generation that doesn’t wait on government and gets back to direct action,” Booker said. “You see it everywhere from Black Lives Matter to the organizing around gun violence after Parkland.”

As a candidate for president, Booker employs a leadership tradition of the black social gospel that reaches back to the racial-justice activism of the late 19th century. Gary Dorrien, the Reinhold Niebuhr professor of social ethics at Union Theological Seminary, traces the civil rights movement back to what became the National Afro-American League in 1890, as well as the Niagara Movement of 1905 to 1909. Its second phase, beginning in 1910, came with the creation of the NAACP; and finally, he argues, a third phase began in 1955, when black people in Montgomery, Alabama, began a bus boycott under the leadership of Martin Luther King Jr. "In every phase, the movement had leaders that espoused the social ethical religion and politics of modern social Christianity," Dorrien wrote in 2015.

As a framework in the fight for civil rights, Dorrien said, the black social gospel “responded to new challenges in a new era of American history.” Its leaders, Dorrien wrote, grappled with the failures of the Reconstruction era, the expansion of Jim Crow segregation, racial lynchings, and “struggles for mere survival in every part of the nation, and the excruciating question of what a new abolition would require.”

This, then, continues into the present, and is where Booker sees the Gen Z activism matching the moment — even if the Black Lives Matter movement grew out of online activism both separate from the religious tradition and purposely decentralized, unlike much of the civil rights movement activism that defined the 20th century. Booker has credited his own trajectory to what King called “the beloved community” — a vision of optimal peace and equality, love, and justice.

Booker offers a vision of the presidency that can serve as an antidote to the law-and-order presidencies of the past.

He continually hits on bringing the “beloved community” ideal to the entire country as president of the United States. Booker offers a vision of the presidency that can serve as an antidote to the law-and-order presidencies of the past; King’s movement was trying to rid America of the “triple evils” of racism, poverty, and militarism.

“The idea that my generation — people born after King, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, and the Kennedys were killed — picked up the torch and has not advanced it is really troublesome to me,” he told me when I saw him in Newark. He ticked off mass incarceration, the black–white wealth gap, and recited a set of bleak homicide statistics "for black men like you and I."

“It’s like, well what have we done?” he said. “We’ve got to find ways to do something about the problems that exist to the insult to a lot of the generation that came before us that opened up so many doors.”

So Booker began to test another message, one designed both to inspire undecided voters and to assuage the concerns of primary voters still rattled by Donald Trump’s 2016 victory: simply beating Trump (“removing one person from one office”) had to be “floor, not the ceiling” of America's political aspirations.

The complicated thing, however, is whether Booker is the one to do all of this in 2019. The message of Jesse Jackson’s 1980s presidential campaigns has resonated among Democrats over the last few years, particularly his unique coalition of and message for black voters, labor, the poor, and farmworkers. From Elizabeth Warren to Kamala Harris, Democrats have spoken about Jackson and met with him. Booker is no different, but perhaps more than others, he echoes the religious-political ethos of Jackson.

But as Andra Gillespie writes in The New Black Politician, a 2012 book about Booker, "while the locus of black leadership has shifted from the activist to the electoral realm, there is still a robust debate about the archetypes and normative goals of effective black leaders.” In a way, Booker is a throwback to an earlier era of black leadership, filtered through religious and centralized power, rather than the dispersed online world of today, in which Meek Mill’s yearslong difficulties with the penal system as he rose to stardom helped propel a real part of the intellectual conversation around race.

What does the articulation of the social gospel look like in 2019? Dorrien, the professor, pointed to a moment that unfolded with Booker watching.

In the Detroit Democratic primary debate, author Marianne Williamson called the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, “just the tip of the iceberg.” She discussed her visit to Denmark, South Carolina, and connected concerns there that the town could become the next Flint to the Trump administration’s gutting of the Clean Water Act. Williamson went on to characterize the problem of environmental injustice as part of “the dark underbelly of American society.”

“The entire conversation that we’re having here tonight — if you think any of this wonkiness is going to deal with this dark psychic force of the collectivized hatred that this president is bringing up in this country, then I’m afraid that the Democrats are going to see some very dark days,” Williamson said. “We need to say it like it is: It’s bigger than Flint. It’s all over this country. It’s particularly people of color, it’s particularly people who do not have the money to fight back. And if the Democrats don’t start saying it, then why would those people feel that they’re there for us?”

To Dorrien, Williamson’s critique of the Democratic field was an opportunity for Booker to distinguish himself as a political leader with more than just a policy message.

“Booker could be claiming [the mantle of the social gospel] in a way that would have integrity and not just as something that he’s latching on to,” Dorrien, who worked on Jackson’s campaigns in the 1980s, said by telephone. “I don’t think he’s tried it, and really, of all those folks up there, he’s the one who could be going for it the most. He would have just planted a memory in people’s heads where he said that he is not someone who is just identified by his policies. It seemed to me that was the chance he had. It doesn’t have to be prompted by Marianne Williamson, but it was there in that moment, and in presidential campaigns, you don’t get that many of them.”

For their part, Booker’s campaign and his allies thinks his folksy allure — the oratorical eloquence, the telegenic air, the goofy earnestness, the hugs, the talk of “radical, defiant” love — can attract justice-focused black Americans everywhere, hit in populist Iowa, and end with Milwaukee’s Democratic National Convention in 2020.

“This is not an election that is turning on what your policy platform is.”

“This is not an election that is turning on what your policy platform is,” said Steve Phillips, the Democratic donor and activist, who worked both of Jackson’s campaigns for president and is a longtime Booker supporter. He explained that Booker is the best candidate to him because he was the most gifted at defining what the battle for the country is, and summoning people to that battle.

“What was Trump’s issue set? It’s not like people rallied to him because he had strong positions on tariffs and trade. It’s that he had an overarching narrative that we have to get back to a time where white people were in charge of this country,” Phillips said. “People flocked to that in enough numbers that he was able to squeak through. What we need is a countervailing leader who can articulate a countervailing message and narrative that this is a multiracial country and we are embracing that in all of its complexities.”

To this end, this summer, in a small conference room at the Westin Hotel in downtown Atlanta, I watched Booker speak to a closed-door prayer breakfast, a black leadership event for Democrats.

He presented himself as a dutiful custodian of the political tradition; he opened by saying that, as a student at Stanford, he cast his first vote for Jackson, who was in the room. He lamented black entrepreneurs’ lack of access to capital, black maternal mortality rates, the kinds of anti-abortion laws passed this year that he called “direct, frontal attacks” on black and low-income women. Booker brought up gun violence and mass incarceration that had become “more than” just the new Jim Crow; look up the numbers, he said, and you’ll see that there are more black people “under criminal supervision in this nation than all the slaves in 1850.”

Ultimately, this built up to an exhortation to vote. When we vote, we win, he said.

He added, “And by ‘we,’ I don’t mean black folks; I mean America wins!”

Booker, however, hasn’t captured hearts with a narrative about America, at least not yet.

For months, he has sat around 2% in national polling — good enough to make it into the third debate in September, not really good enough to show signs of much else. After the half a year he has spent running for president, just about a quarter of Democrats told YouGov pollsters they don’t know enough about Booker to have an opinion — a number more in line with how Democrats see newcomer South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg than how they see Warren or Harris.

Over the last few years, Booker has tried to weave together his “radical love” ethos with condemnation of Trump. After he spoke to the 2016 DNC convention in a primetime speech, Trump tweeted, “If Cory Booker is the future of the Democratic Party, they have no future! I know more about Cory than he knows about himself.” Asked to respond live on CNN, Booker answered matter-of-factly, “I love Donald Trump.” When white nationalists clashed with civilians engaged in a counterprotest in August 2017, Trump said that there were “very fine people on both sides.” Booker said Trump “demonstrated a hateful hypocrisy in failing to name the neo-Nazi, white supremacist, alt-right hate,” and called white nationalism “the evil enemy of our nation’s hope and promise.”

“The focus should not just be about what ‘they’ did in Virginia, but what we will do where we are to advance our nation toward greater justice,” he said.

After a shooter killed 22 and wounded many others in El Paso, Texas, last month, Booker read the suspect’s racist, anti-immigrant manifesto. On TV, he proclaimed that Trump himself was responsible.

“I want to say with more moral clarity that Donald Trump is responsible for this. He is responsible because he is stoking fears and hatred and bigotry,” Booker said.

Booker talks of tragedy being something to rise from, most notably in his speech after the El Paso shooting at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, where, in 2015, a lone white supremacist gunman killed nine, including the senior pastor, Clementa Pinckney. Booker, crisp in his black suit and tie in the visual style of the civil rights generation, spoke eloquently about loss and action.

“Each person, each generation, has a decision to make,” Booker told the church this summer. “Do you want to contribute to our collective advancement or — through inaction or worse — to our collective retrenchment? To our progress or — through apathy and indifference — to the violence that threatens to tear us asunder? That is the challenge of our generation today. It is the collective crossroads we are at.

“Addressing this isn’t an act of charity or philanthropy. It is an issue of national security, it is an issue of patriotism, it is an issue of love.”

The night before his AME speech, down the street from where he spoke with Hillary Clinton in 2016, Booker was as good as I’d ever seen him. At one point, a gentleman asked him what he proposed to do about Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, saying he figured Booker would just want to punch McConnell in the face. Booker discouraged the man from resorting to violence, and afterward he and the man took a selfie. He bantered with a kid named Asher. One voter said she’d been undecided among Warren, Buttigieg, Harris, and Booker, but that seeing Booker solidified her decision. When she told him this, he answered back how grateful he was.

Maybe in the end, the question of whether his campaign takes off is about how meaningful words can be and who is listening. Maybe for Booker to become the thing he’s been working toward for so long, it will require Democrats to, for a little while, experience politics as a high school student craving something positive — about the spirit, the beloved community. As he told me when we were in Newark this spring, “I am shaped by what you and I have just walked through.”

At one point during the tour, I had asked whether, on the chance that he was the Democratic nominee for president against Trump, any of his Republican friends pledged to support him. (Yes, if it would unify the country.) He was talking about his job but stopped answering when someone interrupted, a man with a leaf blower.

“Is that Cory Booker? In the hood!?” he said.

“Yes, sir!” his senator said.

“Thank you! Thank you! Wassup, brother? Thank you, Cory Booker. Can I take this photograph? ... The last place I was expecting to see Cory Booker. Wonderful! Thumbs up! Thank you for coming back to the hood, for staying true to the game! Jesus Christ!”

As Booker walked away, the man turned up his leaf-blowing machinery, as high and as loud as it could go. ●