The Zika virus may cause a wide range of birth defects beyond a severely shrunken brain and skull. That’s according to a trio of studies in mouse and artificial human brain cells published by independent teams on Wednesday.

Since 2015, the Zika virus has spread to more than 40 countries, marked by nearly 1,300 reported cases of microcephaly, or abnormally small heads, in infants in six nations, mostly in northeastern Brazil. The U.S. CDC last month conclusively declared that the virus causes the severe birth defects, two months after the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency over a 20-fold increase in microcephaly cases in Brazil.

“This is probably just the tip of the iceberg,” University of California, San Diego, biologist Alysson Muotri said at a telephone briefing for reporters about one of the new studies.

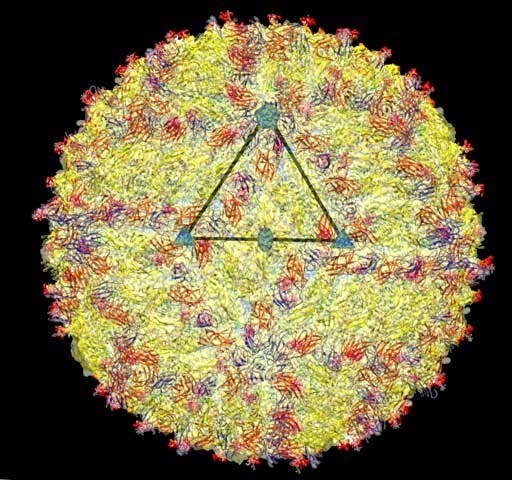

Collectively, the new reports in the journals Nature, Cell, and Cell Stem Cell look at both Brazilian and Asian strains of Zika (first identified in Africa in 1947). They show how the virus crosses the placenta and then kills the particular fetal brain cells that lead to microcephaly — those in the outer layers of the brain tied to higher thinking skills.

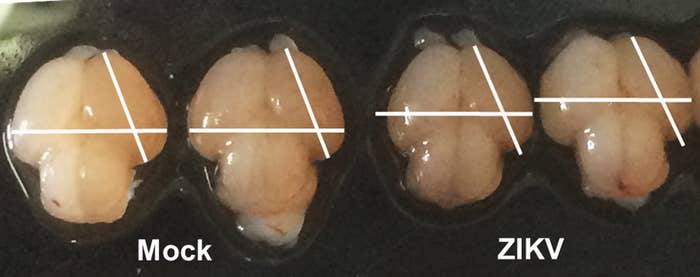

But the research also shows that the virus damages other brain and nerve cells, which could lead to other brain malformations and stunted growth.

The new findings are particularly alarming because many public health experts have worried over whether Zika causes blindness, deafness, and learning disabilities in infected infants, even if they escaped microcephaly. “There is likely more going on,” Muotri said.

“These are really crucial observations,” virologist David O’Connor of the University of Wisconsin told BuzzFeed News. Scientists are playing catch-up in finding animal models for a Zika infection in pregnant women, he said. His own lab is examining how quickly infected monkeys can clear the virus, and whether it lingers for months in pregnant ones, as one study suggested in March.

“We need a lot of animal models to answer different questions in different ways,” O’Connor said. “Science builds on itself. We know a lot more now than we did six months ago, and six months from now we will know a lot more.”

The Zika virus was first recognized as “neurotropic,” preferentially attacking brain and nerve cells, in a 1952 study describing its isolation from a rhesus monkey. Researchers also reported that it killed nerve cells in newborn mice in a 1971 report. But decades went by after the discovery of the virus without reports of birth defects in children until the burst of microcephaly reports came last year in in Brazil. Researchers have subsequently found microcephaly cases in French Polynesia, and researchers now put the odds of microcephaly after a pregnant woman is infected with Zika at somewhere between 1% to 29%.

The surprise of the birth defects tied to Zika’s rapid spread, predicted to infect around 3 million people this year in the Americas, was multiplied by confirmation this year that it is also sexually transmissible — unprecedented for a mosquito-borne virus. The disease can also, rarely, trigger Guillain-Barre syndrome, a paralytic ailment caused by nerve damage.

In the new Nature paper, a largely Brazilian team found that large doses of the virus isolated from a sick human patient in Para, Brazil, last year could infect one kind of mouse, but not another. The virus reproduced the kind of brain damage seen in babies in mouse pups and in human brain cell “organoids” built of a mixture of cell types.

Some researchers had suggested that Zika was interacting with a virus such as dengue to cause birth defects, but the mouse studies argue against the possibility, infectious disease expert Michael Diamond of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis told BuzzFeed News.

“The virus is all you need to have microcephaly,” said Diamond, the senior author on the Cell paper, which focused on how Zika gets past the placenta. This cellular barrier blocks other mosquito-borne diseases, such as dengue and West Nile Virus. Intriguingly, the paper suggests that the mother mouse’s immune system response to the Zika virus may abet its crossover to the fetus.

Muotri and colleagues from Brazil’s University of São Paulo are collaborating with other researchers to compare the genetics of the Brazilian strain of Zika to current African and Asian ones. The hope is to see if any differences explain the birth defect outbreak in Brazil, and answer questions about whether childhood infection with Zika confers long-term immunity to the virus later in life, said Nature paper author Jean Pierre Peron of the University of São Paulo.

“Ultimately we want animal models to develop vaccines or other treatments to help people.”