A race to space is playing out on Earth, aimed at providing everyone on the planet with broadband internet access and sparking a fierce fight for orbital turf among would-be space moguls.

On Monday, Europe's Airbus Group announced at the Paris Air show that it will build 900 internet satellites for OneWeb, a space internet start-up backed by Virgin Galactic billionaire Richard Branson, with a goal to start swathing Earth with internet signals by 2018.

The announcement came just weeks after Elon Musk's SpaceX rocket firm filed plans with the Federal Communications Commission to launch two small experimental "MicroSat" satellites in 2016, in a first step toward a swarm of 4,000 broadband satellites.

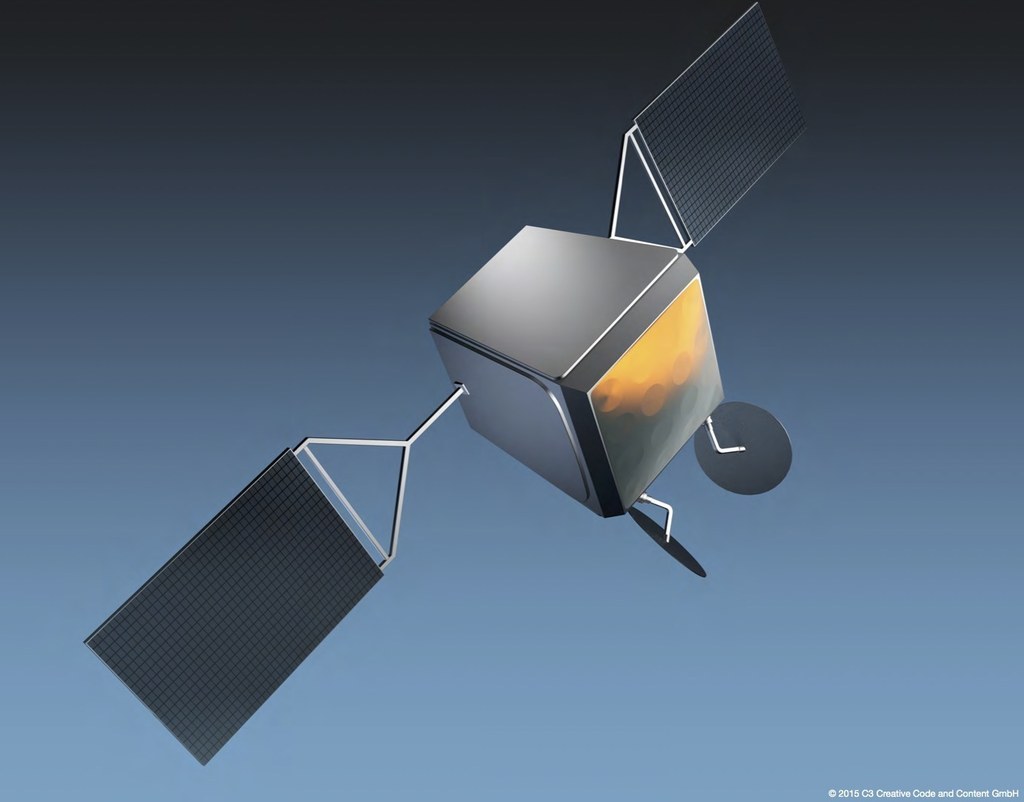

These companies are heralding ever-smaller satellites as the next space revolution.

Older telecommunications satellites — used by the likes of Dish Network and HughesNet — weigh more than 13,000 pounds and fly some 22,000 miles high. Their long distance from Earth means laggy internet connections, loading web pages with a half-second stutter that suffers badly in comparison to fiber optic and cable services on the ground.

Space internet companies are promising much higher speeds by using smaller satellites that are closer to Earth.

The space internet firm O3b, for example, already has eight 1,500-pound satellites circling the globe in a 4,970-mile-high constellation that has become the largest internet provider in the Pacific Ocean region, and a staple of cruise ships.

Much smaller machines — spanning just a few inches, even — are on the way, set to fly just a few hundred miles overhead. If you believe their makers, these small floating cubes will deliver the internet's cacophony where wires can't go, to the countryside and continents lacking in fiber connections, such as Africa.

It's unclear how (and whether) space internet companies will deal with international regulations and insurance costs. But their broad plan, eventually, is to have thousands of microsatellites working together in a network, splitting the labor once done by a single massive satellite among many little ones.

Only some 1,300 active satellites are in orbit now, satellite expert Dave Baiocchi of the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California, told BuzzFeed News, making the proposed broadband satellite constellations look quite ambitious.

"Space is a very big place, so there is room for large [satellite] constellations," Baiocchi said. "We'll just have to see how large."

It’s a sweeping vision, but these space firms still have to prove it can work.

In its FCC filing, SpaceX said that after launching two experimental satellites in 2016, it "plans to deploy a large constellation of small satellites for low-latency, worldwide, high-capacity internet service in the near future."

Airbus, meanwhile, says it will eventually build four satellites a day, each one about three feet tall and 330 pounds, for OneWeb, which is also backed by the communications electronics firm Qualcomm. OneWeb's space broadband constellation will cost less than $2 billion, its founder and CEO Greg Wyler told Reuters.

The jousting between the space broadband rivals is almost incestuous in its intensity.

Wyler had headed Google's space broadband efforts until September, when the search engine giant turned to a proposed balloon-powered internet project called Loon. Next, Wyler reportedly spent time discussing space broadband details with SpaceX late last year, before striking out on his own bid. Then in January, Google and Fidelity backed SpaceX with a $1 billion investment in its rocket-building efforts.

As those moves played out, groups anonymously filed requests with the International Telecommunication Union to claim pieces of the radio spectrum in space, sparking talk of a satellite internet "gold rush" that has tantalized the space industry.

Those filings started the clock for firms to get their space networks on orbit by 2022 or else lose the allotment of radio spectrum they have requested.

In addition to technological hurdles, these firms face unpredictable government regulations and insurance costs.

"The projects are certainly ambitious and the goals are worthy," industry analyst Teresa Mastrangelo of BroadbandTrends in Roanoke, Virginia, told BuzzFeed News by email. "Nonetheless, 4000 satellites, albeit microsatellites, is a lot of objects flying around in space. I imagine it will be an uphill battle to gather government and regulatory approval from nearly every government on this planet."

The largest constellation now in orbit is the Iridium satellite telephone system, with 72 satellites orbiting 485 miles high.

For today's space firms, Iridium is a cautionary tale: It almost went broke after its 1998 start and suffered the unexpected loss of a satellite in a 2009 collision with a defunct Russian military spacecraft. (Iridium is now also contemplating providing internet service with future satellites.)

After a decade of false starts, the advent of smaller and cheaper satellites is making constellations that would dwarf Iridium's look reasonable.

The $2 billion price tag that Wyler estimated for OneWeb is far less than the $9 billion one that doomed Telesdesic, an 840-satellite orbital broadband service backed by Bill Gates in the 1990s.

"Round One to Wyler," wrote satellite industry analyst Tim Farrar on his blog earlier this month, reporting that OneWeb has secured $500 million in funding for its own broadband microsatellite constellation.

Cheaper launch costs allow small satellites to disrupt other parts of the space industry as well. Seattle-based startup BlackSky Global, for example, plans to launch a network of 60 Earth-watching spacecraft as secondary payloads on SpaceX's own Falcon 9 rockets. Backed by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, the firm announced this week that each of its smallsats will weigh 110 pounds, and start launches later this year.

Eventually, the broadband satellites envisioned by SpaceX and OneWeb might be replaced by even smaller "cubesats," boxes just four inches high on each side, according to satellite expert Richard Welle of the Aerospace Corporation in El Segundo, California.

Cubesats could send internet signals by laser instead of radio, cutting power costs even more and obviating the spectrum-hogging behavior that SpaceX complained about in March.

"Pushing that kind of capability down to cubesats means things will get very, very interesting," Welle told BuzzFeed News. "Smaller satellites are just the way the industry is evolving."